Liturgy As Revelation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Version 4 New Orleans ACHA Program.Pages

Thursday, January 3, 2013 1:00 PM-3:00 PM Catholicism in the Sixteenth Century (Marriot, Bacchus Room) Chair: Nelson H. Minnich (Catholic University of America) Sense, Structure, and the Sacraments in Early Sixteenth-Century Glasgow, Daniel MacLeod (University of Guelph) An Anticipated Catholic Humanism: The Role of Early Sixteenth-Century Spanish Dominicans in the Humanistic Articulation of Catholicism, Matthew Kuettel (University of St. Thomas) Intersecting Lives: Erasmus and Pope Adrian VI, Katya Mouris (Catholic University of America) Comment: William J. Connell (Seton Hall University) Twentieth-Century American Catholic Lives: Workers, Political Activists, and Public Intellectuals (Marriott, Bonaparte Room) Chair: Anne Klejment (Univ. of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN) "They Built a Railroad to the Sea”: Workers on the Railroad to Key West, Florida, Francis Joseph Sicius (St. Thomas Univ.) Bishop Mark Hurley and the Settlement of the Student Strike at San Francisco State University in 1969, William Issel (SF State University and Mills College) Neoconservative Catholics: Historical Narratives in Catholic Intellectual Life and the Recovery of Coherence in a Post-Vatican II World, Todd Scribner (Catholic University of America) Comment: The Audience Canadian Catholic Influences in America (Marriott, Regent Room) Chair and Comment: Elizabeth W. McGahan (University of New Brunswick) Searching for Home: Catholicism and the Franco-American Mother, Molly Burns Gallaher (University of New Hampshire) Steel City’s Phantom Heretic: John Hugo and Lacouturite Theology on The Retreat, Jack Downey (La Salle Univ.) Performing Catholicism: Pilgrimage and Clerical Control in Acadian and Cajun Song Repertoire, Marion MacLeod (Memorial University of Newfoundland) 3:30 PM-5:30 PM Health Care, Media, and Education: The Franciscan Experience in the United States (Marriott, Bonaparte Room) Chair: Jeffrey M. -

Sacrorum Antistitum (September 1, 1910)

Theological Studies 71 (2010) SWEARING AGAINST MODERNISM: SACRORUM ANTISTITUM (SEPTEMBER 1, 1910) C. J. T. TALAR The historiography of Modernism has concentrated on the doctrinal issues raised by partisans of reform and their condemnation, to the relative neglect of social and political aspects. Where such connec- tions have been made the linkage has often been extrinsic: those involved in social and political reform subscribed to theses articu- lated by historical critics and critical philosophers. The connections, however, run deeper, reaching into issues surrounding authority and autonomy, ecclesiastical control of not only Catholic intellectual life but also Catholic political and social activity. This article revisits the Oath against Modernism and brings these connections into sharper resolution. “The atmosphere created by Modernism is far from being completely dissipated.”1 T MAY WELL HAVE BEEN THE CASE, given the defects of human nature Iand the effects of original sin, that ecclesiastics on more than one occa- sion violated the second commandment when they considered the effects of Roman Catholic Modernism. The reference to the motu proprio Sacrorum antistitum in my subtitle, however, indicates that a different kind of swear- ing is of interest here. As its centerpiece, the motu proprio promulgated an Oath against Modernism, prefaced by the republication, textually, of the final, disciplinary section of the antimodernist encyclical, Pascendi dominici gregis. Following the oath was an instruction originally addressed in 1894 to the bishops of Italy and to the superiors of religious congregations C. J. T. TALAR received his Ph.D. in sociology from the Catholic University of America and his S.T.D. -

The Social Doctrine of the Church Today

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” The Social Doctrine of the Church Today Christ, the King of the Economy Archbishop Lefebvre and Money Interview With Traditional Catholic Businessmen July - August 2016 It is not surprising that the Cross no longer triumphs, because sacrifice no longer triumphs. It is not surprising that men no longer think of anything but raising their standard of living, that they seek only money, riches, pleasures, comfort, and the easy ways of this world. They have lost the sense of sacrifice” (Archbishop Lefebvre, Jubilee Sermon, Nov. 1979). Milan — fresco from San Marco church, Jesus’ teaching on the duty to render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s; and to God, the things that are God’s. Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Because he is body and soul, man has basic human needs, like food, drink, clothes, and shelter, which he cannot obtain unless he has basic, minimal possessions. The trouble is that possessions quickly engender love for them; love breeds dependence; and depen- dence is only one step away from slavery. Merely human wisdom, like Virgil’s Aeneid, has stigmatized it as “the sacrilegious hunger for gold.” For the Catholic, the problem of material possessions is compounded with the issue of using the goods as if not using them, of living in the world without being of the world. This is the paradox best defined by Our Lord in the first beatitude: “Blessed be the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Our civilization is fast heading towards decomposition partly for not understanding these basic truths. -

Holy Land and Holy See

1 HOLY LAND AND HOLY SEE PAPAL POLICY ON PALESTINE DURING THE PONTIFICATES OF POPES PIUS X, BENEDICT XV AND PIUS XI FROM 1903 TO 1939 PhD Thesis Gareth Simon Graham Grainger University of Divinity Student ID: 200712888 26 July 2017 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction – Question, Hypothesis and Methodology Chapter 2: A Saint for Jerusalem – Pope Pius X and Palestine Chapter 3: The Balfour Bombshell – Pope Benedict XV and Palestine Chapter 4: Uneasy Mandate – Pope Pius XI and Palestine Chapter 5: Aftermath and Conclusions Appendix 1.The Roads to the Holy Sepulchre – Papal Policy on Palestine from the Crusades to the Twentieth Century Appendix 2.The Origins and Evolution of Zionism and the Zionist Project Appendix 3.The Policies of the Principal Towards Palestine from 1903 to 1939 Appendix 4. Glossary Appendix 5. Dramatis Personae Bibliography 3 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION – QUESTION, HYPOTHESIS AND METHODOLOGY 1.1. THE INTRIGUING QUESTION Invitation to Dr Theodor Herzl to attend Audience with Pope Pius X On 25 January 1904, the Feast of the Conversion of St Paul, the recently-elected Pope Pius X granted an Audience in the Vatican Palace to Dr Theodor Herzl, leader of the Zionist movement, and heard his plea for papal approval for the Zionist project for a Jewish national home in Palestine. Dr Herzl outlined to the Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church the full details of the Zionist project, providing assurances that the various Holy Places in Palestine would be “ex-territorialised” to ensure their security and protection, and sought the Pope’s endorsement and support, preferably through the issuing of a pro-Zionist encyclical. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant Papers USGPL.FDGIHG

Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant papers USGPL.FDGIHG This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 28, 2020. Mississippi State University Libraries P.O. Box 5408 Mississippi State 39762 [email protected] URL: http://library.msstate.edu/specialcollections Frederick Dent Grant and Ida Honore Grant papers USGPL.FDGIHG Table of Contents Summary Information ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings ............................................................................................................................... 5 Related Collections ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Collection Inventory ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Series I: Correspondence ................................................................................................................................ -

Pontiff Asks Uthoiics to Assist Fellow

ENCYCUCAL TREATS NEEDS OF MISSIONS Supplement to the Denver Catholic Register N a t i o n a l N a t i o n a l PONTIFF ASKS UTHOIICS S e c t i o n THE S e c t i o n TO ASSIST FELLOW MAN REGISTER (Name Registered in the U. S. Patent Office) MIMtCR OF AUDIT tUNKAU OF CISCULATIONS Ay Migr. J*m*i I. T v c tk TU* Paper Is CotuMcM wltb NCWC WasbInftoB Nrss tMdqusrtsrt br Its Own Lssssd W lru U u Its tiwo John Leads Us to the Messias Vatican City,—Counsels for entrusting ^ a te r SperUI Ssrrtcs. RsIlfMus News Ssrvtcs, Mission Ssrvleos. Rsllflous Nsws Photos and NCWC Plcturo Sorvke responsibility to native Bishops and clergy in the Thursday, December 3, 1959 missions, for training native priests, and, for the first time in an encyclical, an appeal “to all those lay Catholics, wherever they might be, to come LAITY CHALLENGED TO SERVE forward in the professions and in public life to consider seriously the possibility of helping their brothers" are stressed in the fourth encyclical of Love in Action Vital Pope John XXIII’s Pontificate. Fntitled Princept Paxtomm For priests to be able to pen (The Prince of Sbepberda) and etrate the cultured classes, Pope dated Nov. 29, the document Jota instructed Bishops to pro mark! the 40th anniveraary of f i t “centers of culture In which For Aiding Missions 3 another great encyclical on the foreign missionaries and native miasions, Pope Benedict XV's priests may be able to put to Chicago. -

Reflections for Lent Year A

Church of Saint Leo the Great Lincroft, New Jersey Reflections for Lent Year A 1 Lenten Prayer Book composed by Reverend John T. Folchetti, D.Min. Pastor, Church of Saint Leo the Great Dedication His Holiness Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI Who taught us to see the Face of God in Christ Jesus the Eternal Son and His Eminence Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan Archbishop of New York A Good Shepherd and dear friend 2 Introduction Lectio Divina Lectio Divina (Latin for Divine Reading) is a traditional monastic practice of Scriptural reading, meditation and prayer intended to promote communion with God and to increase the knowledge of God’s word. It does not treat Sacred Scripture as texts to be studied, but as God’s living word. Lectio, Meditatio, Oratio, Contemplatio Traditionally, Lectio Divina has four separate steps: a reading of a passage from Sacred Scripture, a reflection on its meaning, followed by prayer and contemplation on the Word of God. Historically, Lectio Divina has been a “community practice”, that is, performed by monks and nuns in monasteries but this practice can be used by an individual and any group, the family in particular. Lectio Divina has been likened to a meal. First, one takes a bite of the food (lectio). The food is then chewed (meditatio), its taste savored (oratio) and finally “digested” and made part of the body (contemplatio). The ultimate purpose of this form of meditative prayer is to lead one to a deeper knowledge of Jesus Christ, the Living Word of God, The Bread of Life. Preparation: Stillness It is very important that an atmosphere of calm and tranquility of mind and body be established before one begins the four traditional steps. -

JOHN HUGO and an AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY of NATURE and GRACE Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences of Th

JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Benjamin T. Peters UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May, 2011 JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Approved by: ________________________________________________________________ William Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _______________________________________________________________ Dennis Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ______________________________________________________________ Kelly Johnson, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Michael Baxter, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _____________________________________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Benjamin Tyler Peters All right reserved 2011 iii ABSTRACT JOHN HUGO AND AN AMERICAN CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF NATURE AND GRACE Name: Peters, Benjamin Tyler University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation examines the theological work of John Hugo by looking at its roots within the history of Ignatian spirituality, as well as within various nature-grace debates in Christian history. It also attempts to situate Hugo within the historical context of early twentieth-century Catholicism and America, particularly the period surrounding the Second World War. John Hugo (1911-1985) was a priest from Pittsburgh who is perhaps best known as Dorothy Day‟s spiritual director and leader of “the retreat” she memorialized in The Long Loneliness. Throughout much of American Catholic scholarship, Hugo‟s theology has been depicted as rigorist and even labeled as Jansenist, yet it was embraced by and had a great influence upon Day and many others. -

4Th Sunday of Easter.Pdf

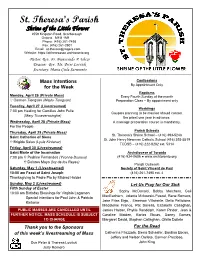

St. Theresa’s Parish Shrine of the Little Flower 2559 Kingston Road, Scarborough Ontario M1M 1M1 Phone: (416) 261-7498 Fax: (416) 261-2901 Email: [email protected] Website: https://sttheresassc.archtoronto.org Pastor: Rev. Fr. Bienvenido P. Ebcas Deacon: Rev. Mr. Peter Lovrick Secretary: Maria Ciela Sarmiento Confessions Mass Intentions By Appointment Only for the Week Baptisms Monday, April 26 (Private Mass) Every Fourth Sunday of the month Carmen Tiongson (Maylu Tiongson) Preparation Class – By appointment only Tuesday, April 27 (Livestreamed) Weddings 7:00 pm Healing for Camillus John Pulle Couples planning to be married should contact (Mary Tisseverasinghe) the priest one year in advance. Wednesday, April 28 (Private Mass) A marriage preparation course is mandatory. For the People Parish Schools Thursday, April 29 (Private Mass) St. Theresa’s Shrine School – (416) 393-5248 Saint Catherine of Siena St. John Henry Newman Catholic School (416) 393-5519 Brigida Salas (Lysle Kintanar) TCDSB – (416) 222-8282 ext. 5314 Friday, April 30 (Livestreamed) Saint Marie of the Incarnation Archdiocese of Toronto 7:00 pm Pedrine Fernandes (Yvonne Dsousa) (416) 934-0606 ● www.archtoronto.org Dolores Mayo (Ivy de los Reyes) Parish Outreach Saturday, May 1 (Livestreamed) Society of Saint Vincent de Paul 10:00 am Feast of Saint Joseph (416) 261-7498 ext. 4 Thanksgiving to Padre Pio by Mildred Halder Sunday, May 2 (Livestreamed) Let Us Pray for Our Sick Fifth Sunday of Easter Sophy McDonald, Bobby Melchers, Gail 10:00 am Birthday Blessings for Virginia Lagamon MacEachern, Jolanta Mirkowski-Paszel, Rene Romero, Special Intentions for Paul John & Patricia Jane Frias Eigo, , Emerson Villarante, Delio Pellicione, Kintanar Madeleine Franco, Pat Savella, Elizabeth Callaghan, PUBLIC MASSES ARE CANCELLED UNTIL James Halder, Phyllis Randolph, Karen Pinder, Jean & FURTHER NOTICE. -

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 13

Pope Benedict XVI - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 13 Pope Benedict XVI From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI (in Latin Benedictus XVI) Benedict XVI was born Joseph Alois Ratzinger on April 16, 1927. He is the 265th and current Pope, the bishop of Rome and head of the Roman Catholic Church. He was elected on April 19, 2005, in the 2005 papal conclave, over which he presided. He was formally inaugurated during the papal inauguration Mass on April 24, 2005. Contents 1 Overview 2 Early life (1927–1951) 2.1 Background and childhood (1927–1943) 2.2 Military service (1943–1945) 2.3 Education (1946–1951) 3 Early church career (1951–1981) 4 Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1981 - 2005) 4.1 Health 4.2 Sex abuse scandal Name Joseph Alois Ratzinger 4.3 Dialogue with other faiths Papacy began April 19, 2005 5 Papacy 5.1 Election to the Papacy Papacy ended Incumbent 5.1.1 Prediction Predecessor Pope John Paul II 5.1.2 Election Successor Incumbent 5.2 Choice of name Born April 16, 1927 5.3 Early days of Papacy Place of birth Marktl am Inn, Bavaria, 6 See also Germany 7 Notes 8 Literature 9 Works 10 See also 11 External links and references 11.1 Official 11.2 Biographical 11.3 General Overview Pope Benedict was elected at the age of 78, the oldest pope since Clement XII (elected 1730) at the start of his papacy. He served longer as a cardinal before being elected pope than any pope since Benedict XIII (elected 1724). -

Freda.Jacobs

OREGOyiAlf. PORTLAND, AUGUST 30. 1914. 6 THE SUNDAY PORTRAITS OF 34 OF THE 66 CARDINALS NOW IN SACRED COLLEGE An Auction Special! Some manufacturing company can get this now at a snap. WHAT ARE WE OFFERED ? Railway Factory Site 200 Feet on O.-- R. & N. Switching Facilities With All Railroads Property 200x290x238x200 Comprising 11-- 7 Acres MAIN BUILDING- - Two-stor- y reinforced con- crete, 42x160 feet. Concrete lower and upper floors and roof of heavy mill construction. WINGS 42x70 ft. Mill construction, covered with metal lath and cement plaster. Small wing, 12x16, solid concrete construction; one story. BOILER HOUSE 16x16, solid concrete, in- r cluding roof. CARPENTER SHOP 20x30 ft., wood con- struction. Buildings are wired for electric power. City gas for use in mechanical work, blast furnaces, etc. Well lighted; windows occupy entire wall space. Solid reinforced concrete vault. Steam 1 I I first-clas- s condition--not as the college of cardinals assembles to heated. Property is all in choose a successor to the late a. over 3 years old. IS The patriarch of Venice himself AMERICAN POPE neither sought nor expected the elec- POPE NAMED 'MID tion in 1903, and his successor may COST $34,000 quite as likely be found outside those who have been most talked of 4s the Mi POSSIBILITY next pope. BARE That he will be an Italian has been UTMOST SECRECY regarded as almost a certainty, for the bargains will be offered at state of affairs throughout Europe is 40 other said to make it more desirable than Hotel, Sept. 10 ever that the church should not part auction at Portland from its traditions.