Working Paper 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title the Malay World in Textbooks: the Transmission of Colonial

The Malay World in Textbooks: The Transmission of Colonial Title Knowledge in British Malaya Author(s) Soda, Naoki Citation 東南アジア研究 (2001), 39(2): 188-234 Issue Date 2001-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/56780 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No.2, September 2001 The Malay World in Textbooks: The Transmission of Colonial Knowledge in British Malaya SODA Naoki* Abstract This paper examines the transmission of colonial knowledge about the Malay world from the British to the Malays in pre-war colonial Malaya. For this purpose, I make a textual analysis of school textbooks on Malay history and geography that were used in Malay schools and teacher training colleges in British Malaya. British and Malay writers of these textbooks not only shared a "scientific" or positivist approach, but also constituted similar views of the Malay world. First, their conceptions of community understood Malay as a bangsa or race and acknowledged the hybridity of the Malays. Second, their conceptions of space embraced the idea of territorial boundaries, understanding Malay territoriality to exist at three levels-the Malay states, Malaya and the Malay world, with Malaya as the focal point. Third, in conceptualizing time, the authors divided Malay history into distinctive periods using a scale of progress and ci vilization. This transmission of colonial knowledge about the Malay world began the localization of the British concept of Malayness, paving the way for the identification of Malay as a potential nation. I Introduction It is now widely acknowledged that social categories in Malaysia such as race and nation are products of the period of British colonialism. -

Perspektif Ilmu Kolonial Tentang Hukum Islam Dan Masyarakat Di Tanah Melayu: Analisis Terhadap Karya-Karya Terpilih

PERSPEKTIF ILMU KOLONIAL TENTANG HUKUM ISLAM DAN MASYARAKAT DI TANAH MELAYU: ANALISIS TERHADAP KARYA-KARYA TERPILIH HALIM @ AB. HALIM BIN ISMAIL AKADEMI PENGAJIAN ISLAM UNIVERSITI MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University2018 of Malaya PERSPEKTIF ILMU KOLONIAL TENTANG HUKUM ISLAM DAN MASYARAKAT DI TANAH MELAYU: ANALISIS TERHADAP KARYA-KARYA TERPILIH HALIM @ AB. HALIM BIN ISMAIL DISERTASI DISERAHKAN SEBAGAI MEMENUHI KEPERLUAN BAGI IJAZAH SARJANA SYARIAH AKADEMI PENGAJIAN ISLAM UNIVERSITI MALAYA UniversityKUALA LUMPUR of Malaya 2018 UNIVERSITI MALAYA PERAKUAN KEASLIAN PENULISAN Nama: HALIM @ AB. HALIM BIN ISMAIL No. Matrik: IGA 150078 Nama Ijazah: SARJANA SYARIAH Tajuk Kertas Projek/Laporan Penyelidikan/ Disertasi/Tesis (“Hasil Kerja ini”): PERSPEKTIF ILMU KOLONIAL TENTANG HUKUM ISLAM DAN MASYARAKAT DI TANAH MELAYU: ANALISIS TERHADAP KARYA-KARYA TERPILIH Bidang Penyelidikan: FIQH Saya dengan sesungguhnya dan sebenarnya mengaku bahawa: (1) Saya adalah satu-satunya pengarang/penulis Hasil Kerja ini; (2) Hasil Kerja ini adalah asli; (3) Apa-apa penggunaan mana-mana hasil kerja yang mengandungi hakcipta telah dilakukan secara urusan yang wajar dan bagi maksud yang dibenarkan dan apa- apa petikan, ekstrak, rujukan atau pengeluaran semula daripada atau kepada mana-mana hasil kerja yang mengandungi hakcipta telah dinyatakan dengan sejelasnya dan secukupnya dan satu pengiktirafan tajuk hasil kerja tersebut dan pengarang/penulisnya telah dilakukan di dalam Hasil Kerja ini; (4) Saya tidak mempunyai apa-apa pengetahuan sebenar atau patut semunasabahnya tahu bahawa -

Legal Pluralism and the East India Company in the Straits of Malacca

Legal Pluralism and the English East India Company in the Straits of Malacca during the Early Nineteenth Century NURFADZILAH YAHAYA During the early nineteenth century, the English East India Company (EIC) was in a state of transition in Penang, an island in the Straits of Malacca off the coast of the Malay Peninsula. Although the EIC had established strong ties with merchants based in Penang, they had failed to convince the EIC government in Bengal to invest them with more legal powers. As a result, they could not firmly extend formal jurisdiction over the region. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty (also known as the Treaty of London) that officially cemented EIC legal authority over the Straits of Malacca, was not signed until 1824, bringing the three Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca, and Singapore under EIC rule officially in 1826. Prior to that, the EIC imposed their ideas of legitimacy on the region via other means, mainly through the co-optation of local individuals of all origins who were identified as polit- ically and economically influential, by granting them EIC military protec- tion, and ease of sailing under English flags. Because co-opted influential individuals could still be a threat to EIC authority in the region, EIC com- pany officials eradicated competing loci of authority by discrediting them in courtroom trials in which they were treated as private individuals. All clients in EIC courts including royal personages in the region were treated like colonial subjects subject to English Common Law. By focusing on a series of trials involving a prominent merchant named Syed Hussain The author is a Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. -

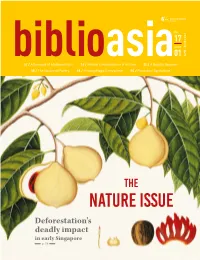

Apr–Jun 2021 (PDF)

Vol. 17 Issue 01 APR–JUN 2021 10 / A Banquet of Malayan Fruits 16 / Nature Conservation – A History 22 / A Beastly Business 38 / The Nature of Poetry 44 / Finding Magic Everywhere 50 / Plantation Agriculture The Nature Issue Deforestation’s deadly impact in early Singapore p. 56 Our cultural beliefs influence how we view the natural environment as well as our understanding Director’s and attitudes towards animals and plants. These views and perceptions impact our relationship with the natural world. Note Some people see nature as wild and chaotic while others view nature as orderly, acting according to natural “laws”. There are those who perceive nature as an economic resource to be exploited for profit or for human enjoyment, yet there are also many who strongly believe that nature should be left untouched to flourish in its natural state. This issue of BiblioAsia looks at how human activities over the past 200 years have affected and transformed our physical environment, and how we are still living with the consequences today. This special edition accompanies an exciting new exhibition launched by the National Library – “Human x Nature” – at the Gallery on Level 10 of the National Library Building on Victoria Street. Do visit the exhibition, which will run until September this year. Georgina Wong, one of the curators of the show, opens this issue by exploring the relationship between European naturalists and the local community as plants and animals new to the West were uncovered. Not unexpectedly, indigenous input was often played down, dismissed, or exoticised. Farish Noor examines this phenomenon by taking a hard look at Walter Skeat’s book Malay Magic. -

The Malay World in Textbooks: the Transmission of Colonial Knowledge in British Malaya

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No.2, September 2001 The Malay World in Textbooks: The Transmission of Colonial Knowledge in British Malaya SODA Naoki* Abstract This paper examines the transmission of colonial knowledge about the Malay world from the British to the Malays in pre-war colonial Malaya. For this purpose, I make a textual analysis of school textbooks on Malay history and geography that were used in Malay schools and teacher training colleges in British Malaya. British and Malay writers of these textbooks not only shared a "scientific" or positivist approach, but also constituted similar views of the Malay world. First, their conceptions of community understood Malay as a bangsa or race and acknowledged the hybridity of the Malays. Second, their conceptions of space embraced the idea of territorial boundaries, understanding Malay territoriality to exist at three levels-the Malay states, Malaya and the Malay world, with Malaya as the focal point. Third, in conceptualizing time, the authors divided Malay history into distinctive periods using a scale of progress and ci vilization. This transmission of colonial knowledge about the Malay world began the localization of the British concept of Malayness, paving the way for the identification of Malay as a potential nation. I Introduction It is now widely acknowledged that social categories in Malaysia such as race and nation are products of the period of British colonialism. For instance, Charles Hirschman argues that "modern 'race relations' in Peninsular Malaysia, in the sense of impenetrable group boundaries, were a byproduct of British colonialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries" [Hirschman 1986: 330]. -

The Common Law of Malaysia in the 21St Century”

(2012) 24 SAcLJ Annual Lecture 2011 1 SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL LECTURE 2011 – “THE COMMON LAW OF MALAYSIA IN THE 21ST CENTURY” The Hon Tun Dato’ Seri ZAKI Tun Azmi Former Chief Justice of Malaysia. I. INTRODUCTION 1 First and foremost I say thank you and express my appreciation to the Right Honorable Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong for inviting me to deliver a talk at this prestigious series of lectures. I must also publicly express my appreciation to the Academy for having arranged my visits to the various places during my stay here. 2 I believe that during the years when I was the Chief Justice, the relationship between the Judiciary and the Bar of Singapore and Malaysia had never been better. To this I must say thank you to Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong. On his suggestion, we formed the annual joint judicial conference which for next year will include Brunei as well. Singapore has also graciously accepted our invitation to attend training and conferences in Malaysia. Likewise Malaysia has done the same in respect of conferences and meetings in Singapore. I am confident that my successor will continue to foster this close relationship and exchanges. 3 When I was asked by Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong to speak on the Common Law of Malaysia in the 21st century, I responded positively without a second thought, thinking it was a straightforward subject. In the course of carrying out my research however, I found out how wrong I had been. In truth, the development of the common law in our jurisdictions is an extensive subject with a multitude of facets. -

Rewriting of the Malay Myth

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Image-i-nation and fictocriticism: rewriting of the Malay myth Nasirin Bin Abdillah University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Bin Abdillah, Nasirin, Image-i-nation and fictocriticism: rewriting of the Malay myth, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2016. -

Kedudukan Perundangan Jenayah Islam Dan Adat Ke Atas Masyarakat Melayu Di Tanah Melayu Menurut Pandangan Orientalis: Rujukan Khusus Terhadap R.O

Kedudukan Perundangan Jenayah Islam Dan Adat Ke Atas Masyarakat Melayu Di Tanah Melayu Menurut Pandangan Orientalis: Rujukan Khusus Terhadap R.O. Winstedt Mohd Farhan, Muhd Imran, Firdaus, Muhamad Khafiz, Nurul Khairiah KEDUDUKAN PERUNDANGAN JENAYAH ISLAM DAN ADAT KE ATAS MASYARAKAT MELAYU DI TANAH MELAYU MENURUT PANDANGAN ORIENTALIS: RUJUKAN KHUSUS TERHADAP R.O. WINSTEDT Mohd Farhan Abd Rahman, Muhd Imran Abd Razak, Ahmad Firdaus Mohd Noor, Muhamad Khafiz Abdul Basir, Nurul Khairiah Khalid Akademi Pengajian Islam Kontemporari (ACIS) Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Perak Kampus Seri Iskandar [email protected] ABSTRAK R.O. Winstedt merupakan seorang orientalis yang berkhidmat di Tanah Melayu sebagai pentadbir British. Bentuk pemikiran beliau berteraskan falsafah positifisme empirik logik iaitu fahaman yang mementingkan penggunaan akal sepenuhnya sebagai pendekatan utama bagi mendapatkan sesuatu fakta keilmuan dengan tepat berdasarkan kaedah penelitian yang sistematik dan teliti. Falsafah ini menolak pembuktian sesuatu fakta menggunakan sumber wahyu kerana dianggap tidak releven dalam pembuktian sejarah. Artikel ini menumpukan kepada analisa terhadap pandangan Winstedt berkaitan undang-undang Jenayah Islam di Tanah Melayu dan pendekatan orientalis dalam menilai Islam dan masyarakat Melayu. Penulis menggunakan kaedah grafisejarah, perbandingan dan analisis kandungan bagi menganalisis pandangan tersebut. Hasil kajian mendapati pendekatan pemikiran orientalis khususnya Winstedt dalam menilai Islam terutamanya sistem perundangan memperlihatkan sudut pandangan yang meragukan dan pertimbangan yang berat sebelah. Winstedt beranggapan undang- undang Islam dan adat tidak boleh dilaksanakan bersama kerana undang-undang Islam pada tanggapan orientalis, kandungannya tidak sesuai untuk diamalkan di Tanah Melayu disebabkan perbezaan budaya dan tempat tinggal. Hal ini berpunca dari kelemahan golongan orientalis dalam memahami kandungan Islam disebabkan latar belakang pemikiran yang berpusatkan Eropah iaitu Euro- centrism. -

English Exhibition Guide

EXHIBITION GUIDE 18 August 2017 – 25 FEBRUARY 2018 EXHIBITION LAYOUT PLAN 1 INTRODUCTION 3 2 WORLD OF MALAY MANUSCRIPTS 2 3 MARKET FOR MANUSCRIPTS 4 4 FROM WRITTEN 1 TO PRINTED 5 ENDURING STORIES 5 ENTRANCE EXIT INTRODUCTION The Malay language played a special role in maritime Southeast Asia. For centuries, it was the language of trade and diplomacy, connecting people who spoke different languages at home with each other and the world outside the region. The widespread use of Malay has been attributed partly to the qualities of the language – its easy pronunciation, simple grammar rules and adaptability to new words. Malay is also a literary language and a language of Islamic discourse in the region. In Tales of the Malay World: Manuscripts and Early Books, explore traditional Malay literary works that have survived in the form of manuscripts, in order to understand the societies that produced and read them. These manuscripts were nearly all written in Jawi (modified Arabic script). Discover also the impact of printing on the manuscript tradition and the growth of the Malay/Muslim printing industry in late- 19th-century Singapore. While printing eventually led to the demise of the Malay manuscript tradition, some stories continue to resonate to this day. Map from Thomas Bowrey’s 1701 Malay–English dictionary 1 WORLD OF MALAY MANUSCRIPTS Our understanding of Malay manuscripts is largely dependent on what has survived. Except for a few written in southern Sumatran scripts, almost all extant Malay manuscripts are written in Jawi. Islam played a prominent role in the development of the Malay written literary tradition. -

“Now We Want Malays to Awake”: Malay Women Teachers in Colonial Johor and Their Legacy

School of Humanities Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences “Now we want Malays to awake”: Malay Women Teachers in Colonial Johor and their Legacy. Anna Maree Doukakis A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales, Australia 2012 Anna Doukakis I ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on Malay women teachers and girls’ schooling in British Malaya during the 1920s and 1930s, when educational opportunities for Malay girls were expanding. It discusses the teachers’ agendas, their roles as leaders, authors and publishers, and their participation in national politics and women’s movements following World War II. The thesis addresses whether and how Malay female pioneers for girls’ education are treated in general and in specialist academic literature. The research also explores the increasing impact of global forces of modernisation in Malaya. It draws on primary and secondary sources in English, Malay and jawi Malay for case studies of: the pioneer of girls’ schooling, Zain bte Sulaiman, who was supervisor of Malay girls’ schools in Johor between 1926 and 1948; the professional association of Malay women teachers in Johor, which she founded, and its publication Bulan Melayu; and the Malay Women’s Training College, the first Malaya-wide residential teacher training institute for Malay female students. Malay women teachers contributed to the form and content of the schools instructing girls using the Malay vernacular. They negotiated with Malaya’s royal and colonial administrators to achieve positions of leadership and influence, and they contributed to the formation of a peninsula-wide Malay identity. -

Sir Richard Winstedt

SIR RICHARD WINSTEDT An era both in Malay studies and in the history of Malaya came to an end when Sir Richard Olaf Winstedt, K.B.B., C.M.G., M.A., D.Litt., LL.D., F.B.A., died at Putney on 2 June 1966. Three years earlier, when he reached his eighty- fifth birthday, his long record of scholarship had been honoured with no less than three Festschriften—special issues of the Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies and of the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and a memorable 357-page book entitled Malayan and Indonesian studies to which 19 of Sir Richard's distinguished admirers had contributed essays. Now a tribute was to be paid to another aspect of his work—his unearthing and fostering of the cultural heritage of the Malays from the very early days of modern Malaya until independence and after. When the news of Sir Richard's death became known, Tunku Abdul Rahman sent a telegram to Lady Winstedt expressing his sorrow and concluding: ' My friend, Sir Richard, has done so much throughout his lifetime for the Malays, whom he has always loved. May his soul rest in peace '. After studying Greats at Oxford the young Winstedt in 1902 joined the Federated Malay States Civil Service (later to be merged into the Malayan Civil Service). He was posted to Perak, a State which had come under British protection only 28 years earlier. At that time the Malays throughout the Peninsula, although a charming and interesting people, were still mainly an illiterate peasantry. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.0 Mukadimah Kajian Ini Akan

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.0 Mukadimah Kajian ini akan membincangkan kerangka utama dalam bahagian pendahuluan, merangkumi latar belakang masalah kajian, pengertian tajuk, persoalan kajian, objektif kajian, skop kajian, metodologi penyelidikan, rangka penulisan, dan penutup. 1.1 Latar Belakang Kajian Kejadian alam yang diciptakan oleh Allah S.W.T mempunyai jutaan rahsia yang belum disingkap manusia. Di dalam al-Qur’an, proses penciptaan langit dan bumi memberi implikasi bahawa wujudnya pencipta yang Maha Esa. Hanya Allah S.W.T yang Maha Esa yang layak disembah dan tiada satu yang mampu menangani kekuasaan- Nya. Konsep kejadian yang dicatatkan di dalam pelbagai karya khususnya karya klasik yang ditulis oleh para ulama di Nusantara secara amnya di Aceh memperlihatkan satu ketika dahulu corak pemikiran berkaitan dengan alam semesta yakni bulan, bintang, tanah, angin, api dan air memberi tunjuk ajar dalam bidang perubatan berdasarkan pengetahuan astronomi dan ilmu falak.1 Hal ini bukan sahaja membuka ruang pola pemikiran dan ideologi di kalangan masyarakat Melayu lama malah masih menjadi 1 Syamsul Bahri, Sejarah Ulama Acheh Di Mesir, ed. ke-51. Modus Acheh Press, April 14, 2010, h.12. 1 pegangan dan kepercayaan oleh masyarakat moden masa kini.2 Antara pemikiran tentang alam terawal difahami manusia ialah kewujudan cakerawala di langit seperti bintang-bintang, planet-planet, bulan dan matahari dengan gambaran buruj yang pelbagai. Hampir semua tamadun awal manusia mempunyai pemikiran yang sama mengenai unsur-unsur tersebut. Pemikiran ini boleh dilihat melalui konsep sains rakyat yakni folk science, termasuk melalui mitos, cerita rakyat dan budaya yang dipraktikkan.3 Di Alam Melayu, kosmologi Hindu-Jawa mengisi pemikiran awal manusia tentang alam.