A Blank Generation: Richard Hell and American Punk Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ventilo173.Pdf

Edito 3 l'environnement.Soit.En ce qui concerne l'économie, un peu chez moi ici, non ? », de faire de son quartier la grève générale permanente avec immobilisation une zone dé-motorisée. L'idée, lancée il y a peu par du pays a un effet non négligeable.Dans le même es- un inconscient, a eu un écho étonnant. De Baille à Li- n°173 prit, on a : piller et mettre le feu au supermarché d'à bération, via La Plaine et Notre Dame du Mont, notre « Mé keskon peu fer ?» « Les hommes politiques sont des méchants et les mé- côté, détruire ou plutôt « démonter » systématique- bande de dangereux activistes (5) a ajouté, lundi soir, dias sont pourris, gnagnagna... » : je commençais à ment les publicités,ne plus rien acheter sauf aux pro- une belle piste cyclable à sa liste de Noël.« Cher Père trouver la ligne éditoriale de ce journal vraiment en- ducteurs régionaux.Bref :un boulot à plein temps.Par Gaudin, je prends ma plus belle bombe de peinture nuyeuse quand un rédacteur,tendu,m'attrapa le bras contre,signalons tout de suite que certaines actions — pour t'écrire. Toi qui est si proche du Saint-Père, par brutalement :« Mé keskon peu fer ? » Sentant que ma écrire dans un journal,manifester temporairement ou nos beaux dessins d'écoliers, vois comme nous aime- blague « voter socialiste, HAhahaha euh.. » ne faisait se réunir pour discuter — n'ont aucun impact, même rions vivre dans un espace de silence, d'oxygène et… plus rire personne, j'ai décidé de me pencher sur la si ça permet de rencontrer plein de filles, motivation et sans bagnoles. -

American Rock with a European Twist: the Institutionalization of Rock’N’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20Th Century)❧

75 American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century)❧ Maria Kouvarou Universidad de Durham (Reino Unido). doi: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit57.2015.05 Artículo recibido: 29 de septiembre de 2014 · Aprobado: 03 de febrero de 2015 · Modificado: 03 de marzo de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo evalúa las prácticas desarrolladas en Francia, Italia, Grecia y Alemania para adaptar la música rock’n’roll y acercarla más a sus propios estilos de música y normas societales, como se escucha en los primeros intentos de las respectivas industrias de música en crear sus propias versiones de él. El trabajo aborda estas prácticas, como instancias en los contextos francés, alemán, griego e italiano, de institucionalizar el rock’n’roll de acuerdo con sus propias posiciones frente a Estados Unidos, sus situaciones históricas y políticas y su pasado y presente cultural y musical. Palabras clave: Rock’n’roll, Europe, Guerra Fría, institucionalización, industria de música. American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century) Abstract: This paper assesses the practices developed in France, Italy, Greece, and Germany in order to accommodate rock’n’roll music and bring it closer to their own music styles and societal norms, as these are heard in the initial attempts of their music industries to create their own versions of it. The paper deals with these practices as instances of the French, German, Greek and Italian contexts to institutionalize rock’n’roll according to their positions regarding the USA, their historical and political situations, and their cultural and musical past and present. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brett Morgen | 160 pages | 05 May 2015 | Insight Editions, Div of Palace Publishing Group, LP | 9781608875498 | English | San Rafael, United States Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck PDF Book You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck makes a persuasive case for its subject without resorting to hagiography -- and includes plenty of rare and unreleased footage for fans. Sign In. Rolling Stone. After Kurt Cobain is born in , his parents move to Aberdeen, Washington and shortly after his sister Kim is born. Kurt Cobain. Archived from the original on November 19, Book Category. After recording their next album, Nevermind , their song " Smells Like Teen Spirit " becomes a hit and the band is launched into the mainstream. Kurt Cobain: Montage Of Heck After a short while, Kurt breaks up with Tracy. Bleach Nevermind In Utero. Helen Razer. Nevertheless, Kyle Anderson of Entertainment Weekly praised the album, considering it as "a cultural artifact that provides an inside look at the creative process of an enigmatic genius. Cobain's mother, Wendy, had regret in relation to working on the film. Archived from the original on February 6, We would have known that story. Downloads Wrong links Broken links Missing download Add new mirror links. We get a very intimate glimpse of the beloved musician from his early years all the way up to , when he tragically took his own life at the age of After he attempts to have sex with the girl, his classmates begin insulting and shaming him. -

Kentucky State Fair Announces Texas Roadhouse Concert Series Lineup 23 Bands Over 11 Nights, All Included with Fair Admission

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ian Cox 502-367-5186 [email protected] Kentucky State Fair Announces Texas Roadhouse Concert Series Lineup 23 bands over 11 nights, all included with fair admission. LOUISVILLE, Ky. (May 26, 2021) — The Kentucky State Fair announced the lineup of the Texas Roadhouse Concert Series at a press conference today. Performances range from rock, indie, country, Christian, and R&B. All performances are taking place adjacent to the Pavilion and Kentucky Kingdom. Concerts are included with fair admission. “We’re excited to welcome everyone to the Kentucky State Fair and Texas Roadhouse Concert series this August. We’ve got a great lineup with old friends like the Oak Ridge Boys and up-and-coming artists like Jameson Rodgers and White Reaper. Additionally, we have seven artists that are from Kentucky, which shows the incredible talent we have here in the Commonwealth. This year’s concert series will offer something for everyone and be the perfect celebration after a year without many of our traditional concerts and events,” said David S. Beck, President and CEO of Kentucky Venues. Held August 19-29 during the Kentucky State Fair, the Texas Roadhouse Concert Series features a wide range of musical artists with a different concert every night. All concerts are free with paid gate admission. “The lineup for this year's Kentucky State Fair Concert Series features something for everybody," says Texas Roadhouse spokesperson Travis Doster, "We look forward to being part of this event that brings people together to create memories and fun like we do in our restaurants.” The Texas Roadhouse Concert Series lineup is: Thursday, August 19 Josh Turner with special guest Alex Miller Friday, August 20 Ginuwine with special guest Color Me Badd Saturday, August 21 Colt Ford with special guest Elvie Shane Sunday, August 22 The Oak Ridge Boys with special guest T. -

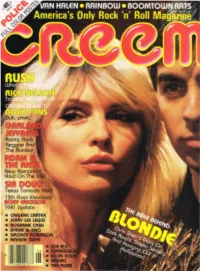

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Negrocity: an Interview with Greg Tate

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2012 Negrocity: An Interview with Greg Tate Camille Goodison CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/731 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NEGROCITY An Interview with Greg Tate* by Camille Goodison As a cultural critic and founder of Burnt Sugar The Arkestra Chamber, Greg Tate has published his writings on art and culture in the New York Times, Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and Jazz Times. All Ya Needs That Negrocity is Burnt Sugar's twelfth album since their debut in 1999. Tate shared his thoughts on jazz, afro-futurism, and James Brown. GOODISON: Tell me about your life before you came to New York. TATE: I was born in Dayton, Ohio, and we moved to DC when I was about twelve, so that would have been about 1971, 1972, and that was about the same time I really got interested in music, collecting music, really interested in collecting jazz and rock, and reading music criticism too. It kinda all happened at the same time. I had a subscription to Rolling Stone. I was really into Miles Davis. He was like my god in the 1970s. Miles, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and locally we had a serious kind of band scene going on. -

{FREE} Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck Ebook

KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brett Morgen | 160 pages | 05 May 2015 | Insight Editions, Div of Palace Publishing Group, LP | 9781608875498 | English | San Rafael, United States Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck - Wikipedia I loved reading Montage of Heck. Aug 04, Farahdiba Khan rated it it was amazing. I have never watched Montage of Heck. It doesn't seems to be available in my country I live in India btw I am happy to read the interviews from Kurt Cobain's family his dad, mom, step-mom and sister , Krist, Tracy and even Courtney. I think these people too are confused about his death. They seem to try to interpret him from their own perceptions. Anyway, I'll be reading more books later. Need to read Tom Grant's book too. I've absolutely adored Kurt Cobain and his life since the literal moment I was born thanks Dad so I have no idea why it took me so long to get around to this. There are so many aspects of Kurt's life which so many people don't know about and having this compilation of his journals and art "All artists are, in a sense, writing their own biographies with their work. There are so many aspects of Kurt's life which so many people don't know about and having this compilation of his journals and art pieces just really summed him up as a person. May 05, Liliana rated it it was amazing. So I've watched the movie and I've read the book. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies.