Politics, Persistence, and Power: the Strategy That Won the French Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recession of 1797?

SAE./No.48/February 2016 Studies in Applied Economics WHAT CAUSED THE RECESSION OF 1797? Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise What Caused the Recession of 1797? By Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts Copyright 2015 by Nicholas A. Curott and Tyler A. Watts About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Prof. Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). About the Authors Nicholas A. Curott ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Economics at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. Tyler A. Watts is Professor of Economics at East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, Texas. Abstract This paper presents a monetary explanation for the U.S. recession of 1797. Credit expansion initiated by the Bank of the United States in the early 1790s unleashed a bout of inflation and low real interest rates, which spurred a speculative investment bubble in real estate and capital intensive manufacturing and infrastructure projects. A correction occurred as domestic inflation created a disparity in international prices that led to a reduction in net exports. Specie flowed out of the country, prices began to fall, and real interest rates spiked. In the ensuing credit crunch, businesses reliant upon rolling over short term debt were rendered unsustainable. The general economic downturn, which ensued throughout 1797 and 1798, involved declines in the price level and nominal GDP, the bursting of the real estate bubble, and a cluster of personal bankruptcies and business failures. -

Mons Memorial Museum Hosts Its First Temporary Exhibition, One Number, One Destiny

1 Press pack PRESS RELEASE From 13 June to 27 September 2015 , Mons Memorial Museum hosts its first temporary exhibition, One number, one destiny. Serving Napoleon . In a unique visitor experience , the exhibition offers a chance to relive the practice of conscription as used during the period of French rule from the Battle of Jemappes (1792) to the Battle of Waterloo (1815). This first temporary exhibition expresses the desire of the new military history museum of the City of Mons to focus on the visitor experience . The conventional setting of the chronological historical exhibition has been abandoned in favour of a far more personal immersion . The basic idea is to give visitors a sense of the huge impact of conscription on the lives of people at the time. With this in mind, each visitor will draw a number by lot to decide whether or not he or she has been ‘conscripted’, and so determine the route taken through the exhibition – either the section presenting the daily existence of conscripts recruited to serve under the French flag, or that focusing on life for the civilians who stayed at home . Visitors designated as conscripts will find out, through poignant letters, objects and other exhibits, about the lives of the soldiers – many of them ill-fated – as they made their way right across Europe in the fight against France’s enemies. Meanwhile, visitors in the other group will learn how those who stayed behind in Mons saw their daily lives turned upside-down by the numerous reforms introduced under the French, including the adoption of a new calendar, the eradication of references to religion, the acquisition of the right to vote, access to a new economic market and exposure to new cultural influences. -

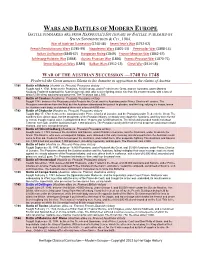

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

The Democratic Societies of the 1790S

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-11-27 “Fire-Brands of Sedition”: The Democratic Societies of the 1790s Carr, Chloe Madison Carr, C. M. (2020). “Fire-Brands of Sedition”: The Democratic Societies of the 1790s (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112798 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “Fire-Brands of Sedition”: The Democratic Societies of the 1790s by Chloe Madison Carr A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2020 © Chloe Madison Carr 2020 ii Abstract The citizen-led Democratic-Republican or Democratic societies in the United States represented a new era of political discourse in the 1790s. Members of these societies, frustrated by their sense that the emerging Federalist executive branch of government was becoming dangerously elitist, and alienated by decision-making in Congress, met regularly to compose resolutions to publish in local and national papers and so make their concerns widely known. Many Federalists, in and out of government, became wary of these societies and their increased presence in the public sphere. -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy. -

American Economic Policy in the 1790S the Significance of The

Founding Choices: American Economic Policy in the 1790s The Significance of the Founding Choices: Editors’ Introduction By Douglas A. Irwin and Richard Sylla Bookstores today are awash with titles that celebrate America’s Founding Fathers as courageous and far‐sighted leaders who not only guided the nation through the difficult period of achieving independence from Britain but also established a system of government that has survived relatively unchanged for more than two centuries. Almost completely ignored in this outpouring of works, however, is a sense for the economic policy achievements of the founders. The neglect of economic policy is surprising when it is considered that the United States of 1790, a relatively small economy with fewer than four million people on the periphery of a European‐centered world and facing a host of economic problems because it had the temerity to declare its independence, would in a century become the world’s largest economy. In two centuries it would become an economic and political colossus with a larger population than any other country except China and India. Those later developments were rooted to a greater extent than is generally appreciated in the economic policy decisions made in the 1790s. This book redresses this neglect by bringing together leading scholars to examine the early economic policies adopted by the new government in the years after 1789. Ratification of the Federal Constitution of 1787 broke the gridlock that afflicted decision‐making about economic policy under the Articles of Confederation. The chapters that follow study the economic policy options that were opened up by the new framework of government, and which choices were implemented. -

Loans in And

LOANS TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY April 2018 – March 2019 The following pictures were on loan to the National British (?) The Fourvière Hill at Lyon (currently Leighton Archway on the Palatine Gallery between April 2018 and March 2019 on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Leighton Houses in Venice *Pictures returned Bürkel Distant View of Rome with the Baths Leighton On the Coast, Isle of Wight of Caracalla in the Foreground (currently on loan Leighton An Outcrop in the Campagna THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST / to the Ashmolean Museum Oxford) Leighton View in Capri (currently on loan HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Buttura A Road in the Roman Campagna to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Fra Angelico Blessing Redeemer Camuccini Ariccia Leighton A View in Spain Gentile da Fabriano The Madonna and Camuccini A Fallen Tree Trunk Leighton The Villa Malta, Rome Child with Angels (The Quaratesi Madonna) Camuccini Landscape with Trees and Rocks Possibly by Leighton Houses in Capri Gossaert Adam and Eve (currently on loan to the Ashmolean Mason The Villa Borghese (currently on loan Leighton Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is carried Museum, Oxford) to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) in Procession through the Streets of Florence Cels Sky Study with Birds Michallon A Torrent in a Rocky Gorge (currently Pesellino Saints Mamas and James Closson Antique Ruins (the Baths of Caracalla?) on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Closson The Cascade at Tivoli (currently on loan Michallon A Tree THE WARDEN AND FELLOWS OF to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Nittis Winter Landscape ALL -

Judicial Foreign Policy: Lessons from the 1790S

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 53 Number 1 The Use and Misuse of History in Article 12 U.S. Foreign Relations Law (Fall 2008) 2008 Judicial Foreign Policy: Lessons From the 1790s David Sloss Santa Clara University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David Sloss, Judicial Foreign Policy: Lessons From the 1790s, 53 St. Louis U. L.J. (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol53/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW JUDICIAL FOREIGN POLICY: LESSONS FROM THE 1790s DAVID SLOSS* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 146 I. BACKGROUND: FRENCH PRIVATEERING IN THE 1790S ............................... 151 II. U.S. NEUTRALITY POLICY: FROM FEBRUARY 1793 TO JUNE 1794 ............ 153 A. Historical Context ....................................................................... 154 B. Substantive Rules Governing Privateers ..................................... 156 1. Sale of Prizes ......................................................................... 156 2. Recruiting U.S. Citizens ........................................................ 158 3. Outfitting Ships in U.S. Ports ............................................... -

Dress in Upper Canada 1790-1840

DRESS IN UPPER CANADA 1790-1840 By Hannah Erika Milliken Bachelor of Arts, Honours, With Distinction University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 2011-2015. A MRP presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Fashion Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018. © Hannah Milliken, 2018. Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Dress in Upper Canada 1790-1840 Master of Arts, 2018 Hannah Erika Milliken Fashion, Ryerson University This MRP aims to uncover unknown details of Canada’s early dress history in the lives of early colonial settlers in Niagara and surrounding Upper Canadian settlements between 1790 and 1840. This study explores the access they had to goods and services, their loyalty to the imperial parent nation of Great Britain, and their adaptability to the conditions of a rudimentary frontier. The central conclusion is that relationships to fashion and dress were remarkably sophisticated in early Upper Canadian societies iii Acknowledgements My sincerest thanks to my supervisor Alison Matthews David for all her help and guidance. -

'Spectacles Within Doors': Panoramas of London in the 1790S Ellis, M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online 'Spectacles within doors': panoramas of London in the 1790s Ellis, M For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/3559 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] August 26, 2008 Time: 09:44am rom024.tex Markman Ellis ‘Spectacles within doors’: Panoramas of London in the 1790s ‘The interest of the panorama is in seeing the increasingly structured by this debate as a true city – the city indoors’. socially-stratified opposition. Wordsworth’s Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project response to the panorama in The Prelude, (1999), 532. although probably based on an experience of In his ramble around London in Book Seven of the exhibition, also reflects his engagement The Prelude (1805), Wordsworth’s poet with the written discourse of the panorama proposes to ‘let us view [...]theSpectacles/ media event. Within doors’. His key example is the Although the panorama dates from the panorama: late-eighteenth century, its modern historiography begins in the late 1960s, when a mimic sights that ape series of publications and research projects first The absolute presence of reality, subjected it to scholarly scrutiny. Pioneering Expressing, as in mirror, sea and land, work by Hubert Pragnell, Scott Wilcox, Richard 1 And what earth is, and what she has to show. Altick and Stephan Oettermann,2 culminated in The panorama is a large-scale landscape Ralph Hyde’s innovative Barbican Art Gallery painting depicting a circular 360 degree view exhibition and catalogue Panoramania! in exhibited under special conditions on the inside 1988.3 This archival work coincided with the surface of a dedicated cylindrical exhibition ‘rediscovery’, preservation and restoration of space. -

Some Franco-Belgian Cases Prof

Castle Talks on Cross-Border Cooperation Crisis of peace? The scars of history: reconciliation in border regions Conflict, Memory, Heritage: some Franco-Belgian cases Prof. Fabienne LELOUP [email protected] • Conflict, collective memory and heritage • About the Franco-Belgian border • Three cases • What to learn? Conflict and Memory (Wagoner et al, 2016; Odak, 2014) Conflict and memory are often two sides of the same coin. • On one hand, conflicts deeply mark the memories of both individuals and collectives. • On the other hand, memory is behind many conflicts, it brings the past into the present and with it the old scars. The study of memory is important in as much as « the past becomes a tool for creating change or stability as well as promoting or inhibiting conflicts” (Wagoner). Conflict and Collective Memory (Wagoner et al, 2016; Odak, 2014) Collective memory suggests that : • shared narratives and symbols of the past are essential for the development of group identity and social life. Taking memory into account can therefore help us to better understand • how certain uses may revive, perpetuate or originate conflicts. In contrast to the dominant cultural tropes that conceptualize memory as a type of repository (either an archive or a monument), we propose “to compare the collective memory of conflict as a wounded body” (Odak). Conflict, Collective Memory and Heritage (Wagoner et al, 2016; Odak, 2014) Collective memory of conflict exhibits ambiguous characteristics: • On one hand, it can serve as a framework for the development of group solidarity and empathy, • on the other hand, it can be a reason for the exclusion and demonization of other groups. -

Elizabeth Drinker: Quaker Values and Federalist Support in the 1790S

Elizabeth Drinker: Quaker Values and Federalist Support in the 1790s Susan Branson At the conclusion of peace between the United States and Britain in 1783, Elizabeth Drinker made a prediction for the succeeding years: "this day was printed the King's speech to both Houses of Parliment Decr. 5"' - bespeaking peace, and Independence; I fear they will not long agreed togeather with us."' Her prediction held true throughout the following decade and beyond. During the 1790s Drinker repeatedly expressed her desire for a "well-regulated government," with leaders who would bring peace and order to society. She was frequently disap- pointed.2 Elizabeth Drinker was a woman deeply concerned about, and intimately involved with, the politics of her time. No significant event passed without comment in her diary. Through a combination of her observation, conversation, and reading, we can piece together the polit- ical ideology of this extraordinary woman. With the experiences of the Revolution fresh in her consciousness, Drinker articulated a Federalist interpretation of government and the construction of a civil society. What Drinker sought, but never experienced, was a peaceful, well- regulated society devoid of contention, factions, and crowd actions. Instead, what she and other Americans witnessed in the 1790s was a period of turbulence both at home and abroad. They lived under a dem- ocratic government in its infancy, still undergoing change and develop- ment. This process was rarely a quiet one. And in Philadelphia, the cap- ital city, the political contentiousness between Federalists and Democratic Republicans generated a great deal of public activity, accompanied in many instances by noise and occasional violence.