We Hold These Truths Dismantling Racial Hierarchies, Building Equitable Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 Hopwood Awards Ceremony

The 2021 Hopwood Awards Ceremony April 14th, 2021 The 2021 Hopwood Program Awards Ceremony April 14th, 2021 Welcome to the virtual 2021 Hopwood Program Awards Ceremony. In an extremely challenging year, we are grateful to the students, faculty, staff, donors, and judges whose participation and support made this year’s awards possible. While a virtual announcement of awards can’t duplicate the excitement of a live event, we hope that you will join us in thanking the contestants and congratulating the winners. We invite you to visit the Hopwood website, https://lsa.umich.edu/hopwood, where in the coming weeks we will post an expanded version of this program featuring photos and bios of the winners. You are also warmly invited to join us Thursday, April 15th from 5:00 to 6:30 p.m. Eastern for a reading and Q&A by Hopwood lecturer Kiese Laymon: https://tinyurl.com/ZellWriters. Order of Events Welcome and Opening Remarks Hopwood Director Meg Sweeney Announcement of Awards Presenters: Meg Sweeney, Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine, Jim Burnstein, Jeremiah Chamberlin, Rebecca Manery Introduction of Hopwood Lecturer Aisha Sabatini Sloan Hopwood Lecture Kiese Laymon Closing Remarks Meg Sweeney Hopwood Committee Ghassan Abou-Zeineddine, Jim Burnstein, Jeremiah Chamberlin Tung-Hui Hu, Laura Thomas, Hannah Webster. Hopwood Staff Meg Sweeney, Hopwood Director Rebecca Manery, Hopwood Program Manager Sarah Miles, Hopwood Program Assistant The 2021 Hopwood Award Contests The Hopwood Contests Graduate and Undergraduate Hopwood Contests Hopwood First- and Second- Year Contests Hopwood Award Theodore Roethke Prize Other Awards Administered by the Hopwood Program • Academy of American Poets • Andrea Beauchamp Prize • Bain-Swiggett Poetry Prize • • Chamberlain Award for Creative Writing • Cora Duncan Award in Fiction • • David Porter Award for Excellence in Journalism • Dennis McIntyre Prize • • Geoffrey James Gosling Prize • Helen J. -

2016 Graduate Profile

Art Institute of Pittsburgh 6 Ashland University Baldwin Wallace University Ball State University Boston University Bowling Green State University Mission Brigham Young University Bryant University Case Western Reserve University Clarion University of Pennsylvania Profile Cleveland Institute of Art 2016 The Mission of the Kenston Cleveland State University Source code: 360860 Local School District is for Colgate University each student to achieve College for Creative Studies Class of 201 Colorado Christian University individual academic excellence Colorado State University and to maximize personal Columbus College of Art & Design Cuyahoga Community College growth in a community which Denison University demonstrates and develops Edinboro University mutual respect, responsibility Gannon University Heriot Watt University, Scotland and life-long learning. Hiram College Hocking College Nancy R. Santilli, Superintendent Iowa State University Kathleen M. Poe, Assistant Superintendent John Carroll University Kent State University Jeremy P. McDevitt, Principal Lakeland Community College Thomas H. Gabram, Principal Liberty College Associate Lourdes College Kathleen Phillips, Assistant Principal Marietta College Rita S. Pressman, Special Education Director Marion Technical College Katherine Detwiler, Guidance Counselor Mercyhurst University Jessica Kardamis, Guidance Counselor Miami University of Ohio New York University Raymond Kimpton, Guidance Counselor North Dakota State University Ohio Northern University Community The Ohio State University Ohio Technical College The Kenston Local School District encompasses Ohio University the townships of Auburn and Bainbridge in Ohio Wesleyan University Geauga County and is adjacent to Chagrin Falls. Otterbein University The system is located in a rapidly growing Parsons The New School Penn State University residential community with an above-average Piedmont College income, twenty-five miles east of downtown Powersport Institute Cleveland. -

Member Colleges

SAGE Scholars, Inc. 21 South 12th St., 9th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 voice 215-564-9930 fax 215-564-9934 [email protected] Member Colleges Alabama Illinois Kentucky (continued) Missouri (continued) Birmingham Southern College Benedictine University Georgetown College Lindenwood University Faulkner Univeristy Bradley University Lindsey Wilson College Missouri Baptist University Huntingdon College Concordia University Chicago University of the Cumberlands Missouri Valley College Spring Hill College DePaul University Louisiana William Jewell College Arizona Dominican University Loyola University New Orleans Montana Benedictine University at Mesa Elmhurst College Maine Carroll College Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Univ. Greenville College College of the Atlantic Rocky Mountain College Prescott College Illinois Institute of Technology Thomas College Nebraska Arkansas Judson University Unity College Creighton University Harding University Lake Forest College Maryland Hastings College John Brown University Lewis University Hood College Midland Lutheran College Lyon College Lincoln College Lancaster Bible College (Lanham) Nebraska Wesleyan University Ouachita Baptist University McKendree University Maryland Institute College of Art York College University of the Ozarks Millikin University Mount St. Mary’s University Nevada North Central College California Massachusetts Sierra Nevada College Olivet Nazarene University Alliant International University Anna Maria College New Hampshire Quincy University California College of the Arts Clark University -

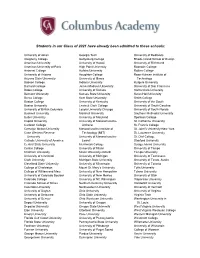

Students in Our Class of 2021 Have Already Been Admitted to These Schools

Students in our Class of 2021 have already been admitted to these schools: University of Akron Georgia Tech University of Redlands Allegheny College Gettysburg College Rhode Island School of Design American University University of Hawaii University of Richmond American University of Paris High Point University Roanoke College Amherst College Hofstra University Rollins College University of Arizona Houghton College Rose-Hulman Institute of Arizona State University University of Illinois Technology Babson College Indiana University Rutgers University Barnard College James Madison University University of San Francisco Bates College University of Kansas Santa Clara University Belmont University Kansas State University Seton Hall University Berea College Kent State University Smith College Boston College University of Kentucky University of the South Boston University Lewis & Clark College University of South Carolina University of British Columbia Loyola University Chicago University of South Florida Bucknell University Marshall University Southern Methodist University Butler University University of Maryland Spelman College Capital University University of Massachusetts- St. Catherine University Carleton College Amherst St. Francis College Carnegie Mellon University Massachusetts Institute of St. John’s University-New York Case Western Reserve Technology (MIT) St. Lawrence University University University of Massachusetts- St. Olaf College Catholic University of America Lowell Stanford University Central State University Merrimack College -

Otterbein Towers March 1938

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Towers Magazine 1926-1999 Archives & Special Collections 3-1938 Otterbein Towers March 1938 Otterbein Towers Otterbein University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/archives_alumnitowers Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein Towers, "Otterbein Towers March 1938" (1938). Towers Magazine 1926-1999. 40. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/archives_alumnitowers/40 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Towers Magazine 1926-1999 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALUMNI NEWS OTTERBEIN COLLEGE Vol. XI. MARCH 1938 No. 7. Scholarship Day Set for April 29 th Otterbein College w ill hold its a nnual Scholan;hip Day on April :Z9. The contest is open •to any high scho·ol senior who ranks in t11e highest third of hi s high school class and wbiose. character can be recommended by hi hig h school princi1)al. H igh school graduat e:' w ho have been out of school on -or two years a nd who have not at tended college are al o eligible. Contestants are required to take a n exa,rni nation in English and m another subject of their own choice. T hree full tuition scholar ~h ips of $200 each a:re awarded to the three highest ranking con testa111ts. In vocal and piano m usic, first 1w ize in ei ther contest 1~ $100 to be appfa:d on tuition, and second prize $50. -

The American Council on Education's 122 Original Member Institutions

American Council on Education THE AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION’S 122 ORIGINAL MEMBER INSTITUTIONS ALABAMA ILLINOIS Alabama Polytechnic Institute De Paul University now Auburn University Eureka College James Millikin University CALIFORNIA now Millikin University California Institute of Technology Knox College Leland Stanford Junior University Northwestern University Mills College Rockford College Occidental College University of Chicago Pomona College University of Illinois University of California YMCA College of Chicago University of Southern California now Roosevelt University COLORADO INDIANA Colorado College Butler College Colorado State Teachers’ College DePauw University now University of Northern Colorado Rose Polytechnic Institute University of Colorado University of Notre Dame CONNECTICUT IOWA Connecticut College Cornell College Wesleyan University Grinnell College Yale University Iowa State Teachers College now University of Northern Iowa DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Luther College Catholic University of America Union College of Iowa Upper Iowa University GEORGIA Brenau College ACE Original Member Institutions KANSAS MINNESOTA Baker University Carleton College Washburn College College of St. Catherine College of St. Olaf KENTUCKY College of St. Teresa Centre College College of St. Thomas Georgetown College Hamline University University of Kentucky Macalester College University of Minnesota MAINE Bowdoin College MISSOURI Kirksville State Teachers’ College MARYLAND now Truman State University Goucher College Southeast Missouri State -

The Search for a President

Westerville, Ohio The Search for a President O t t e r b e i n U n i v e r s i t y • t h e s e a r c h f O r a P r e s i d e n t • 1 t h e O ppo r t U n i t y O tterbein University is a private, residential comprehensive bachelors and masters degrees in an environment that encourages Master’s institution in Westerville, Ohio and home to nearly 3,000 service-learning, provides a liberal arts core, and develops students. It was founded in 1847 and is associated with the United students as globally aware citizens ready to embark on successful Methodist Church. In 2010, its name was reverted from Otterbein and impactful professional careers. College to Otterbein University to reflect the increasing array of Dr. Kathy A. Krendl, who has been leading the university graduate and undergraduate programs offered. for eight years, has well positioned Otterbein for continued The Otterbein University Board of Trustees invites success. Launching new academic partnerships, diversifying applications and nominations for the position of president. revenue streams, strengthening partnerships with business and Otterbein’s 21st president will succeed Dr. Kathy A. Krendl who will be retiring in June, 2018 after nine years of exceptional presidential leadership. Otterbein University has a history as a national leader and a college of opportunity. The university included women as faculty members and as students from its founding, and was the first institution in the nation to be founded co-educational. -

Consumer Information - Financial Aid and Understanding Your Award

Consumer Information - Financial Aid and Understanding Your Award OTTERBEIN FINANCIAL AID PRINCIPLES Otterbein coordinates balanced and effective financial programs. Financial assistance from Otterbein is supplemental to all other resources, such as: contributions from the family, a percentage of savings, earnings, state and federal grants, loans and scholarships. In addition to awarding merit-based scholarships, the University assists admitted students who demonstrate financial eligibility. Otterbein is committed to making your education financially attainable through gift aid and self-help aid. Otterbein scholarships are awarded for a four-year period provided the student meets the provided on the award notification. Need-based financial aid awards may have loan and work expectations. FINANCIAL AID AWARD Your Financial Aid Award is based upon eligibility for various programs. Need-based eligibility is determined through the yearly completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). FAFSA’s may be submitted as of October 1st of the year prior to the academic year for which you are applying. Otterbein’s priority filing deadline is February 15th before the start of that academic year. The award may consist of one type of aid or any combination of scholarships, grants loans or work-study eligibility. Additional instructions regarding your offer of aid will be explained on your “Financial Aid Award”, “Understanding Your Payment Options” and on “Banner” through the Student Portal, “O-Zone.” Since your aid award is determined using many variables, please inform the Office of Student Financial Services about any changes to the information you have provided, in particular, if your enrollment level or housing status changes. -

2016 Mhs College Fair

2016 MHS COLLEGE FAIR AIC College of Design Defiance College Kettering University Albion College Denison University Lake Erie College Allegheny College DePauw University Lincoln Memorial University American University Drexel University Lipscomb University Antonelli College Duquesne University Manchester University Art Academy of Cincinnati Earlham College Marian University - Indianapolis Ashland University Eastern Kentucky University Marietta College Baldwin-Wallace University Elon University Marshall University Ball State University Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Maryville University-St. Beckfield College Louis Empire Beauty Schools Miami University Regionals Bellarmine University FIDM/ Fashion Institute of Belmont Abbey College Design & Merchandising Miami University, Oxford Bluffton Univeristy Florida Southern College Morehead State University Bowling Green State Franklin University Mount Ida College University Gannon University Mount St. Joseph University Bucknell University Georgia Institute of Mount Vernon Nazarene Butler University Technology University Case Western Reserve Good Samaritan School of Muskingum University Nursing University Northern Kentucky GROOVE U - (music University Cedarville University industry career program) Nova Southeastern Central Michigan University Hanover College University Central State University Hiram College Ohio Christian University Centre College Hocking College Ohio Dominican University Cincinnati Christian Illinois Institute of Ohio Northern University University Technology Cincinnati State -

How Student Development Is Enhanced Through Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation: Perspectives from the Campus Centers

How Student Development is Enhanced Through Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation: Perspectives from the Campus Centers January 22, 2020 The Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) Effort • Launched by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation in 2016, TRHT is a national and community-based process to plan for and bring about sustainable change, and to address the historic and contemporary effects of racism. • AAC&U is partnering with higher education institutions to develop TRHT Campus Centers to prepare the next generation of strategic leaders and critical thinkers to break down racial hierarchies and dismantle the belief in the hierarchy of human value. The TRHT Campus Centers • Adelphi University • Stockton University • Andrews University • The Citadel, The Military • Austin Community College College of South Carolina • Big Sandy Community and • University of Arkansas– Technical College Fayetteville • Brown University • University of California, Irvine • Dominican University • University of Hawai’i at • Duke University Mānoa • George Mason University • University of Maryland • Hamline University Baltimore County • Marywood University • The Charlotte Racial Justice Consortium (University of • Millsaps College North Carolina Charlotte, • Otterbein University Johnson C. Smith University, • Rutgers University—Newark and Queens University of • Southern Illinois University– Charlotte) Edwardsville • University of Puget Sound • Spelman College The TRHT Framework Restoring to Wholeness: Racial Healing for Ourselves, Our Relationships and Our Communities W. K. Kellogg Foundation, December 2017 “Before you can transform systems and structures, you must do the people work first.” Racial Healing Circles: Empathy and Liberal Education by Gail C. Christopher Diversity & Democracy Summer 2018 Vol.21 No.3 "Rx Racial Healing . brings together a diverse group of people in the safe, respectful environment of a racial healing circle. -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

Albright College Alfred University Alvernia University American

Organizations attending Montgomery County Regional College Fair Albright College Alfred University Alvernia University American College Dublin American University Arcadia University ASU Admission Services Binghamton University Bloomsburg University of PA Bryn Athyn College Cabrini University Cairn University California University of PA Carleton College Cazenovia College Cedar Crest College CEFAM Central Penn College Central Pennsylvania Diesel Institute Chatham University Chestnut Hill College Cheyney University Cheyney University Christopher Newport University Clarion University of Pennsylvania Clarkson University Coastal Carolina University Colgate University College Planning Service America LLC Columbus College of Art & Design Delaware Valley University DeSales University Drexel University Duquesne University East Stroudsburg University of PA Eastern University Edinboro University Elizabethtown College Elmira College Elon University Fairleigh Dickinson University Flagler College Florida Institute of Technology Full Sail University Gannon University Georgia Southern University Gettysburg College Goldey-Beacom College Gwynedd Mercy University Harcum College Harrisburg University Hartwick College High Point University Hofstra University Holy Family University Hood College Hunter College Immaculata University Indiana University of Pennsylvania Ithaca College Ithaca College James Madison University Jefferson University John Cabot University Keiser University Kenyon College Keystone College King's College Kutztown University of Pennsylvania