Robin Hood and the Forest Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Ward Map (PDF)

BRIDGE ST V N OAKLAWN R WESTOVER A B CHANDLER ST HORACE MANNAV GEMINI CT C P RICH FERRELL AV REIDSVILLE ARLINE CT R GLIDEWELL CT P R SEVENTH AND A RLINE D B HARMON D I DARTMOUTH RD FOREST DR AV W EIGHTH ST H L R TIMBE W A R OAK N AV E MOUNT ZION PL M M E A U LIBERTY ONE-HALF ST AV V TANDERS ST T B RD A R MILL RD D Y A A D B A A V N T M ST FILE ST C R TRAVIS ST V VALLEYMEADE PEACHTREE T N M A E H H A NB52 E EIGHTH ST E S VIEW CT S Y A S L O AV GRAY L R R H W SEVENTH ST L A S J CADILLAC ST D D A L W A E L D T L X CT E M T FERRELL CT A B R E MEADOWS CR M A S W E WILEYAV N E N SUNNYFIELD R D R E Y A I N Y N Y W I O E L O O R A T V BUICK ST O M KATHERINE I N A L E L D HOLIDAY ST L M L PEACH SUMMEREST CT CAROLINA CR V G EDISON E R E A R L V D A L D D R E E Y L BANBURY RD R R S R G MEADOWLAND B A O N TRADE ST N A R A R M R T I A L Y D D B L RIDGE DR R N A ST U D D D H N W C N A D T HILL DR S N E R CT M D Y S IN D I E G MIAMI AV CANAL DR N N EV O C V D U G R E S O A D D S T L S E BISCAYNE ST U N L R E R U N E S R T T R D N E O T E D G O L R O E T K H V G R L E DS D C A BIG S E STRATTONAV E D OLONIA T L NOL L ANGELO ST S NEW W R R R Y S D SNOW CHARLESTON T R D N RE W E ICKFOR G X P A N N MARTIN D O N R CARL RUSSELLAV L R D L R N W E PL W W DO R U E SIXTH ST A S RMEA V D O Y ST R E EE GARDEN LN N H A CT T D O DR O E T V R B IX LUTHER NASH AV N SUN F MADISON L S NPATTERSON AV E N W O N D T X N HIGHLANDAV N D D I M KOURY DR U L A ROLLING CT CLUB PARK RD LINDEN ST DR F T T L SUMMIT ST A N KING JR DR U PLACE CR MASON ST BROOK DR S N CHERRY ST PRINCE -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

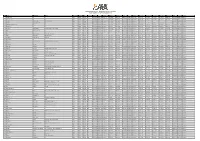

Outlaw Triathlon 2012 - Provisional Results: Version 4 Email Enquiries - [email protected]

OUTLAW TRIATHLON 2012 - PROVISIONAL RESULTS: VERSION 4 EMAIL ENQUIRIES - [email protected] POS NAME SURNAME CLUB RACE NO. GENDER CAT CAT POS. SWIM T1 BIKE SPLIT 1 BIKE SPLIT 2 BIKE SPLIT 3 BIKE T2 RUN SPLIT 1 RUN SPLIT 2 RUN SPLIT 3 RUN SPLIT 4 RUN SPLIT 5 RUN SPLIT 6 RUN FINISH NOTES 1 GI TRI CLUB 936 TEAM TEAM 1 00:57:09 00:01:06 00:26:14 02:35:55 03:31:17 04:28:33 00:00:17 00:21:44 01:39:31 01:17:59 01:39:31 02:18:32 02:42:00 03:23:07 08:50:14 Finished 2 THE SHERIFFS 977 TEAM TEAM 2 00:50:05 00:02:01 01:41:33 02:49:44 03:55:32 05:04:40 00:00:19 00:18:07 00:35:59 01:07:27 01:25:49 01:59:22 02:19:42 02:55:46 08:52:53 Finished 3 HARRY WILTSHIRE DRIVIN TO TRI 918 MALE 25/29 1 00:48:35 00:01:49 01:41:53 02:48:00 03:49:02 04:53:29 00:02:33 00:20:55 00:42:44 03:19:47 09:06:16 Finished 4 CHRIS GOODFELLOW 231 MALE 30/34 1 00:54:48 00:02:53 00:31:27 02:48:13 03:49:33 04:53:21 00:02:50 00:20:12 00:40:41 01:16:52 01:38:09 02:16:17 02:39:16 03:17:25 09:11:19 Finished 5 CANCER RESEARCH UK 929 TEAM TEAM 3 00:55:25 00:00:45 00:36:06 02:57:42 04:00:51 05:04:58 00:00:16 00:20:24 00:40:27 01:16:32 01:37:51 02:14:35 02:36:11 03:14:17 09:15:44 Finished 6 DAWN 2 934 TEAM TEAM 4 01:03:09 00:00:54 01:48:57 02:59:59 04:09:10 05:22:17 00:00:19 00:19:29 00:38:12 01:11:09 01:30:23 02:04:21 02:23:59 02:59:07 09:25:50 Finished 7 NATHAN BRADFORD CLIMB ON BIKES HEREFORD 205 MALE 30/34 2 00:59:28 00:02:00 00:32:17 02:56:08 03:58:13 05:02:49 00:02:02 00:21:26 00:42:11 01:19:17 01:40:12 02:18:22 02:41:09 03:19:39 09:26:01 Finished 8 JOHN WHITWORTH 304 MALE 30/34 -

King John in Fact and Fiction

W-i".- UNIVERSITY OF PENNS^XVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WALLERSTEIN ff DA 208 .W3 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARY ''Ott'.y^ y ..,. ^..ytmff^^Ji UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WAIXE510TFIN. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GiLA.DUATE SCHOOL IN PARTLVL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 'B J <^n5w Introductory LITTLE less than one hundred years after the death of King John, a Scottish Prince John changed his name, upon his accession to L the and at the request of his nobles, A throne to avoid the ill omen which darkened the name of the English king and of John of France. A century and a half later, King John of England was presented in the first English historical play as the earliest English champion and martyr of that Protestant religion to which the spectators had newly come. The interpretation which thus depicted him influenced in Shakespeare's play, at once the greatest literary presentation of King John and the source of much of our common knowledge of English history. In spite of this, how- ever, the idea of John now in the mind of the person who is no student of history is nearer to the conception upon which the old Scotch nobles acted. According to this idea, John is weak, licentious, and vicious, a traitor, usurper and murderer, an excommunicated man, who was com- pelled by his oppressed barons, with the Archbishop of Canterbury at their head, to sign Magna Charta. -

March 2009 Newsletter

MARCH 2009 NEWSLETTER March Calendar of Events That's Science Fiction Tuesday March 3, 2009 7:00 pm - 9:00 pm Fantasy Gamers Group Hillsdale Public Library Saturday March 21, 2009 201.358.5072 2:30 pm - 7:30 pm Shadow of the Vampire (2000). Reality's Edge Game Store Seville Diner follows the movie - 289 Broadway, Westwood,NJ. Ridge Road North Arlington, NJ Suspense Central Explore the freaky world of HP Lovecraft's Cthulu mythos as writer, Monday March 9, 2009 gamer, and veteran GM BJ Pehush takes the reigns for a story of 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm gangland murders, strange beings, and terror beyond imagining as Borders @ Garden State Plaza we explore the town of Arkham. This game will use the 6th edition 201.712.1166 Call of Cthulu This month's selection is LAMB: The Gospel According to Bif, Chaosium rules (books available for order through New Moon Christs' Childhood Pal by Christopher Moore. Comics). Drawing A Crowd Themes of the Fantastic Wednesday March 11, 2009 Tuesday March 24, 2009 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm New Moon Comics New Moon Comics 973-81-COMIC or 973-812-6642 973-81-COMIC or 973-812-6642 Discussion group re: comic books. Topic discussion group www.newmooncomics.com. www.newmooncomics.com. Whispers from Beyond & Face the Fiction Modern Masters Saturday March 14, 2009 Friday March 27, 2009 7:00 pm - 8:00pm (Whispers From Beyond) 8:00pm - 10:00 pm 8:00 pm - 10:00 pm (Face The Fiction) Borders Ramsey Interstate Shopping Center Borders Ramsey Interstate Shopping Center 201.760.1967 201.760.1967 This month we discuss Christopher Moore's Bloodsucking This month's guest is bestselling horror writer, L.A. -

Sherwood Forest National Nature Reserve Oyster Fungus on Birch, Birklands

Sherwood Forest National Nature Reserve Oyster fungus on birch, Birklands Introduction In the heart of Nottinghamshire lie the ancient forests of Birklands and Budby, an extensive area of old pasture-woodland and heathland on the dry nutrient-poor soils © Peter Wakely/Natural England © Peter Wakely/Natural of the Sherwood Sandstone. Together they represent a rare and wonderful fragment of the great forest of Sherwood, one of the most famous forests in the world. Today, over 420 hectares of this internationally important forest is now managed as a National Nature Reserve (NNR). © Peter Wakely/Natural England © Peter Wakely/Natural Ancient wood-pasture, Birklands “By itself it stands, and is like no other spot on which my eyes have looked, or my feet have ever England © Peter Wakely/Natural trod. It is Birkland...” (Charles Reece Pemberton, 1835). Woodland glade, Birklands History Birklands, which is an old Viking word meaning ‘birch land’, was first mentioned in documents in 1251 and is likely to be at least one thousand years old. It was part of the vast Royal Forest of Sherwood that once covered over 41,000 hectares of the county. The wood remained the property of the Crown for nearly 600 years and was used as a source of timber, grazing land and as an exclusive hunting ground rich with wild deer for successive kings and queens of England. Contrary to popular opinion, much of the historic Sherwood Forest was, in fact, tree-less, being dominated by wild open plains of heathland such as Budby South Forest. This uncultivated forest land was once grazed by wild deer, rabbits and livestock; and its trees, gorse and bracken were collected by local people for fuel and fodder. -

Sherwood Forest Country Park Contents

Survey of Visitors August 2015 Sherwood Forest Country Park Contents PART 1 Survey Aims & Objectives Methodology Sample Size & Location PART 2 Visitor Characteristics PART 3 Visitor Experience PART 4 Summary & Key Findings Part 1 Aims & Objectives Methodology Sample Size & Location Survey Aims & Objectives This survey was commissioned by Nottinghamshire County Council’s Country Park Service to gauge current visitor satisfaction at Sherwood. This is part of an annual programme of visitor insight research and includes: • Demographic profile of visitors • Frequency of visits • Places visited once at the destination • Specific insights into ‘tourist’ visitors • Effectiveness of local promotion / visitor guides • Assessment of service delivery perceptions • Measurement of visitor satisfaction Where possible comparisons will be drawn with previous surveys to identify improvement or decline but this will not be possible in all cases as survey questions and formats have changed over time. Methodology The survey took place over seven days during the school summer holidays from Monday 10 th August – Sunday 16 th August 2015. This was the week immediately following the Park’s annual Robin Hood Festival. It was conducted during August to mirror the dates of previous visitor surveys and to provide clearer year-on-year comparisons. The survey was based on face-to-face interviews with visitors and three researchers were involved in the project. Researchers used Ipad tablet devices to quickly capture information. Questionnaires were programmed with icons, images, sliders and radio buttons to illustrate points and engage interviewees. Methodology The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions which were designed and agreed in advance with the Park Development Officer. -

Volume 1, Issue 1 2017 ROBIN HOOD and the FOREST LAWS

Te Bulletin of the International Association for Robin Hood Studies Volume 1, Issue 1 2017 ROBIN HOOD AND THE FOREST LAWS Stephen Knight The University of Melbourne The routine opening for a Robin Hood film or novel shows a peasant being harassed for breaking the forest laws by the brutal, and usually Norman, authorities. Robin, noble in both social and behavioral senses, protects the peasant, and offends the authorities. So the hero takes to the forest with the faithful peasant for a life of manly companionship and liberal resistance, at least until King Richard returns and reinstates Robin for his loyalty to true values, social and royal, which are somehow congruent with his forest freedom. The story makes us moderns feel those values are age-old. But this is not the case. The modern default opening is not part of the early tradition. Its source appears to be the very well-known and influential Robin Hood and his Merry Men by Henry Gilbert (1912). The apparent lack of interest in the forest laws theme in the early ballads might simply be taken as reality: Barbara A. Hanawalt sees a strong fit between the early Robin Hood poems and contemporary outlaw actuality. Her detailed analysis of what outlaws actually did against the law indicates that robbery and assault were normal and that breach of the forest laws was never an issue.1 The forest laws themselves are certainly medieval.2 They were famously imposed by the Norman kings, they harassed ordinary people, stopping them using the forests for their animals and as a source for food and timber, and Sherwood was one of the most aggressively policed forests—but this did not cross into the early Robin Hood materials. -

<I>Medieval Cultural Studies: Essays in Honour Of

208 Reviews details. These, Duffy shows, were frequently crossed out, erased or changed by later owners, particularly when the Reformation made dangerous any relics of Catholic ‘superstitions’. In examining the life of prayer and the meditation to which it presumably gave rise, Duffy considers how far the individual felt personally the apparent sentiments of the prayers in the books, such as the psalms. He examines the additional materials that owners added to their copies to assess what their personal preoccupations might be, concentrating on one or two representative examples rather than producing statistics that would necessarily be of doubtful validity. Some of the additional prayers are effectively charms or sympathetic magic. As time passed, he shows, the books’ contents became somewhat standardised with a heavy emphasis on the moral and didactic. They also included a greater percentage of vernacular material. He judges the English version to be particularly distinct in the amount of supernaturalism that they contain, material that he thinks Continental bishops were able to exclude from editions in their dioceses. The Reformation, however, altered the acceptable form of prayers and although the Books of Hours did not vanish overnight, the editions in the first half of Elizabeth’s reign were evidently not in demand as their approach seemed alien to Protestant ideas of Christian prayer. Perhaps the most interesting chapter is the one in which he turns his attention to the annotations that Sir Thomas More made in the Book of Hours that he took to the Tower with him and clearly used while he was there. While More was a powerful religious thinker, Duffy shows that others in their own books expressed similar sentiments and that these sentiments are as much communal as they are individual. -

Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham

Early Theatre 14.1 (2011) Alexis Butzner ‘Sette on foote with gode Wyll’: Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham Lythe and listin, gentilmen, That be of frebore blode; I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode. A Gest of Robyn Hode1 In the greenwood of England, a game is afoot. Robin Hood, the noble ban- dit, has been identified as the audacious hero of Sherwood and Barnsdale for centuries, and his constant presence in ballads and drama since the four- teenth century attests to his popularity in and influence on the culture of the English nation. In a manuscript fragment of the late fifteenth century,2 the legend finds incarnation in a twenty-one-line drama (forty-two, if the caesurae are recognized instead as line-breaks), known by most scholars as Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham. The text contains no indication of scene-divisions or stage directions, and does not offer any notation to indi- cate the identity of the various speakers. Because the text offers so little in the way of definite answers, it invites interpretation. Despite their admirable efforts to treat the fragment, however, scholars have reached little consensus: critics, while advancing the probable accuracy of their own reconstructions, have yet to resolve some crucial difficulties that arise in the extant text. By reading the script Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham as a single and complete play-text, as I do in this re-examination, readers may reconcile its apparent inconsistencies. Since the first extant record of Robin Hood in literature, in the four- teenth century Piers Plowman, tales and rhymes of the legendary outlaw have permeated Anglophone culture — a feat of public memory that, according to Stephen Knight, is surpassed only by stories of King Arthur.3 That the Robin Hood legend survives — and thrives — should not come as a shock; 61 62 Alexis Butzner even in his earliest incarnations, he occupies a liminal space between social strata. -

2019 ARF Calendar

Arlington Rose Foundation (ARF) 2019 Calendar of Events Website: www.arlingtonrose.org Updated February 15, 2019 Events are free tp the public except where otherwise noted Updates, changes and new events may occur. Members are notified by e-mail. January 20, Sunday at midnight - Annual Cash Awards Digital Photography Contest- Award rules published in newsletter and sent online to all members. Deadline for submittal is January 20 at midnight. Contact 703-371-9351 with questions. February 10, Sunday 2-4 pm - Floral Arrangement Workshop- Floral designer and instructor Tricia Smith guides participants in techniques for designing French inspired rose arrangements. Create and take home your own arrangement. Bring your sweetheart, medium tall vase and pruners. $10 for members, $25 for newcomers which includes a one year ARF membership/ benefits. Location: TwinBrook Floral Design, 4151 Lafayette Center Dr. Suite 110B, Chantilly, VA (703) 978-3700. February 16, Saturday 9:30 -11am- Coffee in McLean, StarNut Gourmet, 1445 Laughlin Ave, McLean, VA Talk roses with ARF growers over coffee. Our treat. February 24, Sunday 2-4pm - Know & Grow Country Store Product Seminar- Learn how to apply proven products to grow amazing roses. Save time and money. Speakers: ARF Consulting Rosarians. Location: Merrifield Garden Center - Fair Oaks. Free. March 2, Saturday 6pm - Country Store orders due to Country Store manager, Sylvia Henderson. E-mail: [email protected]. ARF members only. March 8 & 9, Friday & Saturday - Pre-spring District Seminars in Staunton, VA . Rose growing programs and fellowship. For more information: go to www.colonialdistrictroses.org. Registration required. March 16 & 17, Saturday 10-2 pm, Sunday 10 to Noon- Pick up for Country Store garden products at Merrifield Garden Center 12101 Lee Highway, Fairfax, VA in the OVERFLOW PARKING LOT. -

Treacherous 'Saracens' and Integrated Muslims

TREACHEROUS ‘SARACENS’ AND INTEGRATED MUSLIMS: THE ISLAMIC OUTLAW IN ROBIN HOOD’S BAND AND THE RE-IMAGINING OF ENGLISH IDENTITY, 1800 TO THE PRESENT 1 ERIC MARTONE Stony Brook University [email protected] 53 In a recent Associated Press article on the impending decay of Sherwood Forest, a director of the conservancy forestry commission remarked, “If you ask someone to think of something typically English or British, they think of the Sherwood Forest and Robin Hood… They are part of our national identity” (Schuman 2007: 1). As this quote suggests, Robin Hood has become an integral component of what it means to be English. Yet the solidification of Robin Hood as a national symbol only dates from the 19 th century. The Robin Hood legend is an evolving narrative. Each generation has been free to appropriate Robin Hood for its own purposes and to graft elements of its contemporary society onto Robin’s medieval world. In this process, modern society has re-imagined the past to suit various needs. One of the needs for which Robin Hood has been re-imagined during late modern history has been the refashioning of English identity. What it means to be English has not been static, but rather in a constant state of revision during the past two centuries. Therefore, Robin Hood has been adjusted accordingly. Fictional narratives erase the incongruities through which national identity was formed into a linear and seemingly inevitable progression, thereby fashioning modern national consciousness. As social scientist Etiénne Balibar argues, the “formation of the nation thus appears as the fulfillment of a ‘project’ stretching over centuries, in which there are different stages and moments of coming to self-awareness” (1991: 86).