Ivanhoe Summary.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Ward Map (PDF)

BRIDGE ST V N OAKLAWN R WESTOVER A B CHANDLER ST HORACE MANNAV GEMINI CT C P RICH FERRELL AV REIDSVILLE ARLINE CT R GLIDEWELL CT P R SEVENTH AND A RLINE D B HARMON D I DARTMOUTH RD FOREST DR AV W EIGHTH ST H L R TIMBE W A R OAK N AV E MOUNT ZION PL M M E A U LIBERTY ONE-HALF ST AV V TANDERS ST T B RD A R MILL RD D Y A A D B A A V N T M ST FILE ST C R TRAVIS ST V VALLEYMEADE PEACHTREE T N M A E H H A NB52 E EIGHTH ST E S VIEW CT S Y A S L O AV GRAY L R R H W SEVENTH ST L A S J CADILLAC ST D D A L W A E L D T L X CT E M T FERRELL CT A B R E MEADOWS CR M A S W E WILEYAV N E N SUNNYFIELD R D R E Y A I N Y N Y W I O E L O O R A T V BUICK ST O M KATHERINE I N A L E L D HOLIDAY ST L M L PEACH SUMMEREST CT CAROLINA CR V G EDISON E R E A R L V D A L D D R E E Y L BANBURY RD R R S R G MEADOWLAND B A O N TRADE ST N A R A R M R T I A L Y D D B L RIDGE DR R N A ST U D D D H N W C N A D T HILL DR S N E R CT M D Y S IN D I E G MIAMI AV CANAL DR N N EV O C V D U G R E S O A D D S T L S E BISCAYNE ST U N L R E R U N E S R T T R D N E O T E D G O L R O E T K H V G R L E DS D C A BIG S E STRATTONAV E D OLONIA T L NOL L ANGELO ST S NEW W R R R Y S D SNOW CHARLESTON T R D N RE W E ICKFOR G X P A N N MARTIN D O N R CARL RUSSELLAV L R D L R N W E PL W W DO R U E SIXTH ST A S RMEA V D O Y ST R E EE GARDEN LN N H A CT T D O DR O E T V R B IX LUTHER NASH AV N SUN F MADISON L S NPATTERSON AV E N W O N D T X N HIGHLANDAV N D D I M KOURY DR U L A ROLLING CT CLUB PARK RD LINDEN ST DR F T T L SUMMIT ST A N KING JR DR U PLACE CR MASON ST BROOK DR S N CHERRY ST PRINCE -

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

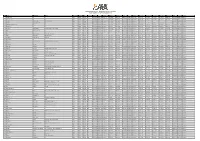

Outlaw Triathlon 2012 - Provisional Results: Version 4 Email Enquiries - [email protected]

OUTLAW TRIATHLON 2012 - PROVISIONAL RESULTS: VERSION 4 EMAIL ENQUIRIES - [email protected] POS NAME SURNAME CLUB RACE NO. GENDER CAT CAT POS. SWIM T1 BIKE SPLIT 1 BIKE SPLIT 2 BIKE SPLIT 3 BIKE T2 RUN SPLIT 1 RUN SPLIT 2 RUN SPLIT 3 RUN SPLIT 4 RUN SPLIT 5 RUN SPLIT 6 RUN FINISH NOTES 1 GI TRI CLUB 936 TEAM TEAM 1 00:57:09 00:01:06 00:26:14 02:35:55 03:31:17 04:28:33 00:00:17 00:21:44 01:39:31 01:17:59 01:39:31 02:18:32 02:42:00 03:23:07 08:50:14 Finished 2 THE SHERIFFS 977 TEAM TEAM 2 00:50:05 00:02:01 01:41:33 02:49:44 03:55:32 05:04:40 00:00:19 00:18:07 00:35:59 01:07:27 01:25:49 01:59:22 02:19:42 02:55:46 08:52:53 Finished 3 HARRY WILTSHIRE DRIVIN TO TRI 918 MALE 25/29 1 00:48:35 00:01:49 01:41:53 02:48:00 03:49:02 04:53:29 00:02:33 00:20:55 00:42:44 03:19:47 09:06:16 Finished 4 CHRIS GOODFELLOW 231 MALE 30/34 1 00:54:48 00:02:53 00:31:27 02:48:13 03:49:33 04:53:21 00:02:50 00:20:12 00:40:41 01:16:52 01:38:09 02:16:17 02:39:16 03:17:25 09:11:19 Finished 5 CANCER RESEARCH UK 929 TEAM TEAM 3 00:55:25 00:00:45 00:36:06 02:57:42 04:00:51 05:04:58 00:00:16 00:20:24 00:40:27 01:16:32 01:37:51 02:14:35 02:36:11 03:14:17 09:15:44 Finished 6 DAWN 2 934 TEAM TEAM 4 01:03:09 00:00:54 01:48:57 02:59:59 04:09:10 05:22:17 00:00:19 00:19:29 00:38:12 01:11:09 01:30:23 02:04:21 02:23:59 02:59:07 09:25:50 Finished 7 NATHAN BRADFORD CLIMB ON BIKES HEREFORD 205 MALE 30/34 2 00:59:28 00:02:00 00:32:17 02:56:08 03:58:13 05:02:49 00:02:02 00:21:26 00:42:11 01:19:17 01:40:12 02:18:22 02:41:09 03:19:39 09:26:01 Finished 8 JOHN WHITWORTH 304 MALE 30/34 -

THE WIZARD of OZ an ILLUSTRATED COMPANION to the TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC by John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan with a Foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini

THE WIZARD OF OZ AN ILLUSTRATED COMPANION TO THE TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC By John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan With a foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini The Wizard of Oz: An Illustrated Companion to the Timeless Movie Classic is a vibrant celebration of the 70th anniversary of the film’s August 1939 premiere. Its U.S. publication coincides with the release of Warner Home Video’s special collector’s edition DVD of The Wizard of Oz. POP-CULTURE/ ENTERTAINMENT over the rainbow FALL 2009 How Oz Came to the Screen t least six times between April and September 1938, M-G-M Winkie Guards); the capture and chase by The Winkies; and scenes with HARDCOVER set a start date for The Wizard of Oz, and each came and went The Witch, Nikko, and another monkey. Stills of these sequences show stag- as preproduction problems grew. By October, director Norman ing and visual concepts that would not appear in the finished film: A Taurog had left the project; when filming finally started on the A • Rather than being followed and chased by The Winkies, Toto 13th, Richard Thorpe was—literally and figuratively—calling the shots. instead escaped through their ranks to leap across the castle $20.00 Rumor had it that the Oz Unit first would seek and photograph whichever drawbridge. California barnyard most resembled Kansas. Alternately, a trade paper re- • Thorpe kept Bolger, Ebsen, and Lahr in their Guard disguises well ported that all the musical numbers would be completed before other after they broke through The Tower Room door to free Dorothy. -

The Comment, October 29, 1981

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1981 The ommeC nt, October 29, 1981 Bridgewater State College Volume 55 Number 17 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1981). The Comment, October 29, 1981. 55(17). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/491 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. l I l -j THE COM ENT i Dear Joe, page· 3 Triumph! page 7 Vol. LV, Issue 17 Bridgewater State College October 29, 1981 Bridgewater Junior Saves Life of Friend by Michael Ricciardi Joseph Cifello is a police officer the woman from· choking. Joseph for the town of Rockland. He is also knew that this was only driving the in his junior year at BSC. Last choking material farther into her Thurs, Oct 22, Mr. Cifello was one throat. After what seemed like of forty honored guests at a banquet hours Cifello, pushing the chef out sponsored by the American Blue of the way, tried three times unsuc Cross, Blue Shield. He and the cessfully to dislodge the food from other 39 guests personally received her throat. On the fourth try he suc .awards from Dr. Henry Hiemlech, ceeded in dislodging the food from inventor of a first aid maneuver the woman's throat. It was not until known as the "Hiemlich hug". some time later that Joseph fully It all began some four years ago realized what he had done. "When I when Mr. Cifello was at home got home it hit me:.1 had saved a watching a morning talk show. -

King John in Fact and Fiction

W-i".- UNIVERSITY OF PENNS^XVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WALLERSTEIN ff DA 208 .W3 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARY ''Ott'.y^ y ..,. ^..ytmff^^Ji UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WAIXE510TFIN. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GiLA.DUATE SCHOOL IN PARTLVL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 'B J <^n5w Introductory LITTLE less than one hundred years after the death of King John, a Scottish Prince John changed his name, upon his accession to L the and at the request of his nobles, A throne to avoid the ill omen which darkened the name of the English king and of John of France. A century and a half later, King John of England was presented in the first English historical play as the earliest English champion and martyr of that Protestant religion to which the spectators had newly come. The interpretation which thus depicted him influenced in Shakespeare's play, at once the greatest literary presentation of King John and the source of much of our common knowledge of English history. In spite of this, how- ever, the idea of John now in the mind of the person who is no student of history is nearer to the conception upon which the old Scotch nobles acted. According to this idea, John is weak, licentious, and vicious, a traitor, usurper and murderer, an excommunicated man, who was com- pelled by his oppressed barons, with the Archbishop of Canterbury at their head, to sign Magna Charta. -

Scena Del Film "Athena E Le Sette Sorelle" - Regia Richard Thorpe - 1954 - Attori Jane Powell, Louis Calhern, Edmund Purdom, Steve Reeves

SIRBeC scheda AFRLIMM - IMM-PV250-0000857 Scena del film "Athena e le sette sorelle" - regia Richard Thorpe - 1954 - attori Jane Powell, Louis Calhern, Edmund Purdom, Steve Reeves Thorpe, Richard Link risorsa: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede/IMM-PV250-0000857/ Scheda SIRBeC: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/fotografie/schede-complete/IMM-PV250-0000857/ SIRBeC scheda AFRLIMM - IMM-PV250-0000857 CODICI Unità operativa: PV250 Numero scheda: 857 Codice scheda: IMM-PV250-0000857 Visibilità scheda: 3 Utilizzo scheda per diffusione: 03 Tipo di scheda: AFRLIMM SOGGETTO SOGGETTO Indicazioni sul soggetto Sul palcoscenico di un teatro, si riconoscono al centro Jane Powell (Athena Mulvain), Louis Calhern (Grandpa Ulysses Mulvain), Edmund Purdom (Adam Calhorn Shaw), Steve Reeves (Ed Perkins) e a sinistra un gruppo di ballerine Identificazione Scena del film "Athena e le sette sorelle" - regia Richard Thorpe - 1954 - attori Jane Powell, Louis Calhern, Edmund Purdom, Steve Reeves Nomi [1 / 4]: Powel, Jane Nomi [2 / 4]: Calhern, Louis Nomi [3 / 4]: Purdom, Edmund Nomi [4 / 4]: Reeves, Steve CLASSIFICAZIONE Altra classificazione: fiction / scena di genere THESAURUS [1 / 4] Descrittore: interni THESAURUS [2 / 4] Descrittore: spettacolo THESAURUS [3 / 4] Descrittore: abbigliamento THESAURUS [4 / 4] Descrittore: suppellettili Pagina 2/10 SIRBeC scheda AFRLIMM - IMM-PV250-0000857 LUOGO E DATA DELLA RIPRESA LOCALIZZAZIONE Stato: Stati Uniti d'America Occasione: Scena del film "Athena e le sette sorelle" (Athena) - regia di Richard -

12-04-2018 Traviata Eve.Indd

GIUSEPPE VERDI la traviata conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, production Michael Mayer based on the play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils set designer Christine Jones Tuesday, December 4, 2018 costume designer 8:00–11:00 PM Susan Hilferty lighting designer New Production Premiere Kevin Adams choreographer Lorin Latarro DEBUT The production of La Traviata was made possible by a generous gift from The Paiko Foundation Major additional funding for this production was received from Mercedes T. Bass, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S la traviata conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance violet ta valéry annina Diana Damrau Maria Zifchak flor a bervoix giuseppe Kirstin Chávez Marco Antonio Jordão the marquis d’obigny giorgio germont Jeongcheol Cha Quinn Kelsey baron douphol a messenger Dwayne Croft* Ross Benoliel dr. grenvil Kevin Short germont’s daughter Selin Sahbazoglu gastone solo dancers Scott Scully Garen Scribner This performance Martha Nichols is being broadcast live on Metropolitan alfredo germont Opera Radio on Juan Diego Flórez SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Tuesday, December 4, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Diana Damrau Chorus Master Donald Palumbo as Violetta and Musical Preparation John Keenan, Yelena Kurdina, Juan Diego Flórez Liora Maurer, and Jonathan -

Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham

Early Theatre 14.1 (2011) Alexis Butzner ‘Sette on foote with gode Wyll’: Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham Lythe and listin, gentilmen, That be of frebore blode; I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode. A Gest of Robyn Hode1 In the greenwood of England, a game is afoot. Robin Hood, the noble ban- dit, has been identified as the audacious hero of Sherwood and Barnsdale for centuries, and his constant presence in ballads and drama since the four- teenth century attests to his popularity in and influence on the culture of the English nation. In a manuscript fragment of the late fifteenth century,2 the legend finds incarnation in a twenty-one-line drama (forty-two, if the caesurae are recognized instead as line-breaks), known by most scholars as Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham. The text contains no indication of scene-divisions or stage directions, and does not offer any notation to indi- cate the identity of the various speakers. Because the text offers so little in the way of definite answers, it invites interpretation. Despite their admirable efforts to treat the fragment, however, scholars have reached little consensus: critics, while advancing the probable accuracy of their own reconstructions, have yet to resolve some crucial difficulties that arise in the extant text. By reading the script Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham as a single and complete play-text, as I do in this re-examination, readers may reconcile its apparent inconsistencies. Since the first extant record of Robin Hood in literature, in the four- teenth century Piers Plowman, tales and rhymes of the legendary outlaw have permeated Anglophone culture — a feat of public memory that, according to Stephen Knight, is surpassed only by stories of King Arthur.3 That the Robin Hood legend survives — and thrives — should not come as a shock; 61 62 Alexis Butzner even in his earliest incarnations, he occupies a liminal space between social strata. -

2019 ARF Calendar

Arlington Rose Foundation (ARF) 2019 Calendar of Events Website: www.arlingtonrose.org Updated February 15, 2019 Events are free tp the public except where otherwise noted Updates, changes and new events may occur. Members are notified by e-mail. January 20, Sunday at midnight - Annual Cash Awards Digital Photography Contest- Award rules published in newsletter and sent online to all members. Deadline for submittal is January 20 at midnight. Contact 703-371-9351 with questions. February 10, Sunday 2-4 pm - Floral Arrangement Workshop- Floral designer and instructor Tricia Smith guides participants in techniques for designing French inspired rose arrangements. Create and take home your own arrangement. Bring your sweetheart, medium tall vase and pruners. $10 for members, $25 for newcomers which includes a one year ARF membership/ benefits. Location: TwinBrook Floral Design, 4151 Lafayette Center Dr. Suite 110B, Chantilly, VA (703) 978-3700. February 16, Saturday 9:30 -11am- Coffee in McLean, StarNut Gourmet, 1445 Laughlin Ave, McLean, VA Talk roses with ARF growers over coffee. Our treat. February 24, Sunday 2-4pm - Know & Grow Country Store Product Seminar- Learn how to apply proven products to grow amazing roses. Save time and money. Speakers: ARF Consulting Rosarians. Location: Merrifield Garden Center - Fair Oaks. Free. March 2, Saturday 6pm - Country Store orders due to Country Store manager, Sylvia Henderson. E-mail: [email protected]. ARF members only. March 8 & 9, Friday & Saturday - Pre-spring District Seminars in Staunton, VA . Rose growing programs and fellowship. For more information: go to www.colonialdistrictroses.org. Registration required. March 16 & 17, Saturday 10-2 pm, Sunday 10 to Noon- Pick up for Country Store garden products at Merrifield Garden Center 12101 Lee Highway, Fairfax, VA in the OVERFLOW PARKING LOT. -

Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani 14

Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani 14 a cura di Concetta Assenza Pubblicazione dell’A.Ri.M. – Associazione Marchigiana per la Ricerca e Valorizzazione delle Fonti Musicali QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI 14/2016 a cura di Concetta Assenza ASSOCIAZIONE MARCHIGIANA PER LA RICERCA E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLE FONTI MUSICALI (A.Ri.M. – onlus) via P. Bonopera, 55 – 60019 Senigallia www.arimonlus.it [email protected] QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI Volume 14 Comitato di redazione Concetta Assenza, Graziano Ballerini, Lucia Fava, Riccardo Graciotti, Gabriele Moroni Realizzazione grafica: Filippo Pantaleoni ISSN 2421-5732 ASSOCIAZIONE MARCHIGIANA PER LA RICERCA E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLE FONTI MUSICALI (A.Ri.M. – onlus) QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI Volume 14 a cura di Concetta Assenza In copertina: Particolare dell’affresco di Lorenzo D’Alessandro,Madonna orante col Bambino e angeli musicanti, 1483. Sarnano (MC), Chiesa di Santa Maria di Piazza. La redazione del volume è stata chiusa il 30 giugno 2016 Copyright ©2016 by A.Ri.M. – onlus Diritti di traduzione, riproduzione e adattamento totale o parziale e con qualsiasi mezzo, riservati per tutti i Paesi. «Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani» – nota Lo sviluppo dell’editoria digitale, il crescente numero delle riviste online, l’allargamento del pubblico collegato a internet, la potenziale visibilità globale e non da ultimo l’abbattimento dei costi hanno spinto anche i «Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani» a trasformarsi in rivista online. Le direttrici che guidano la Rivista rimangono sostanzialmente le stesse: particolare attenzione alle fonti musicali presenti in Regione o collegabili alle Marche, rifiuto del campanilismo e ricerca delle connessioni tra storia locale e dimensione nazionale ed extra-nazionale, apertura verso le nuove tendenze di ricerca, impostazione scientifica dei lavori. -

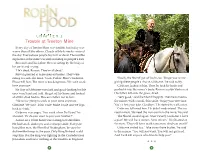

Robin Hood Was Smiling

CHAPTER 1 Trouble at Treeton Mine Every day at Treeton Mine was terrible, but today was worse than all the others. Clouds of black smoke covered the sky. Everywhere people lay hurt or dead. The terrible explosion at the mine was still sounding in people’s ears. Rowan found his father. He was sitting by the body of his uncle and crying. ‘He’s dead, Rowan. They’re all dead.’ Rowan pointed at some men on horses. They were riding towards the mine. ‘Look, Father. Here’s Gisborne. Slowly, the Sheriff got off his horse. ‘I hope you’re not Please tell him. The mine is too dangerous. We can’t work giving these people a choice, Gisborne,’ he said softly. here anymore.’ Gisborne looked at him. Then he took his knife and Sir Guy of Gisborne was dark and good-looking but his pushed it into the miner’s body. Rowan couldn’t believe it. eyes were hard and cold. He got off his horse and looked His father fell onto the grass, dead. at all the dead bodies. Rowan’s father ran to him. ‘Very good,’ said the Sheriff happily. Then he turned to ‘We’re not going to work in your mine anymore, the miners with a small, thin smile. ‘Enjoy your free time. Gisborne. We can’t. It isn’t safe. Make it safe and we’ll go You’ve lost your jobs. Goodbye.’ He started to walk away. back to work.’ Gisborne followed him. He didn’t understand. ‘But we Gisborne was angry. ‘You work when I tell you!’ he need miners.