Allie If You Talk About an Assemblage of Plants Near the Monument…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMNP Mountains Manual 2017

Mountain Adventures Manual utahmasternaturalist.org June 2017 UMN/Manual/2017-03pr Welcome to Utah Master Naturalist! Utah Master Naturalist was developed to help you initiate or continue your own personal journey to increase your understanding of, and appreciation for, Utah’s amazing natural world. We will explore and learn aBout the major ecosystems of Utah, the plant and animal communities that depend upon those systems, and our role in shaping our past, in determining our future, and as stewards of the land. Utah Master Naturalist is a certification program developed By Utah State University Extension with the partnership of more than 25 other organizations in Utah. The mission of Utah Master Naturalist is to develop well-informed volunteers and professionals who provide education, outreach, and service promoting stewardship of natural resources within their communities. Our goal, then, is to assist you in assisting others to develop a greater appreciation and respect for Utah’s Beautiful natural world. “When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” - Aldo Leopold Participating in a Utah Master Naturalist course provides each of us opportunities to learn not only from the instructors and guest speaKers, But also from each other. We each arrive at a Utah Master Naturalist course with our own rich collection of knowledge and experiences, and we have a unique opportunity to share that Knowledge with each other. This helps us learn and grow not just as individuals, but together as a group with the understanding that there is always more to learn, and more to share. -

High-Resolution Correlation of the Upper Cretaceous Stratigraphy Between the Book Cliffs and the Western Henry Mountains Syncline, Utah, U.S.A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of Sciences 5-2012 HIGH-RESOLUTION CORRELATION OF THE UPPER CRETACEOUS STRATIGRAPHY BETWEEN THE BOOK CLIFFS AND THE WESTERN HENRY MOUNTAINS SYNCLINE, UTAH, U.S.A. Drew L. Seymour University of Nebraska, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss Part of the Geology Commons, Sedimentology Commons, and the Stratigraphy Commons Seymour, Drew L., "HIGH-RESOLUTION CORRELATION OF THE UPPER CRETACEOUS STRATIGRAPHY BETWEEN THE BOOK CLIFFS AND THE WESTERN HENRY MOUNTAINS SYNCLINE, UTAH, U.S.A." (2012). Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 88. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss/88 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HIGH-RESOLUTION CORRELATION OF THE UPPER CRETACEOUS STRATIGRAPHY BETWEEN THE BOOK CLIFFS AND THE WESTERN HENRY MOUNTAINS SYNCLINE, UTAH, U.S.A. By Drew L. Seymour A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For Degree of Master of Science Major: Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Under the Supervision of Professor Christopher R. Fielding Lincoln, NE May, 2012 HIGH-RESOLUTION CORRELATION OF THE UPPER CRETACEOUS STRATIGRAPHY BETWEEN THE BOOK CLIFFS AND THE WESTERN HENRY MOUNTAINS SYNCLINE, UTAH. U.S.A. Drew L. Seymour, M.S. -

Saline Soils and Water Quality in the Colorado River Basin: Natural and Anthropogenic Causes Gabriel Lahue River Ecogeomorphology Winter 2017

Saline soils and water quality in the Colorado River Basin: Natural and anthropogenic causes Gabriel LaHue River Ecogeomorphology Winter 2017 Outline I. Introduction II. Natural sources of salinity and the geology of the Colorado River Basin IIIA. Anthropogenic contributions to salinity – Agriculture IIIB. Anthropogenic contributions to salinity – Other anthropogenic sources IV. Moving forward – Efforts to decrease salinity V. Summary and conclusions Abstract Salinity is arguably the biggest water quality challenge facing the Colorado River, with estimated damages up to $750 million. The salinity of the river has doubled from pre-dam levels, mostly due to irrigation and reservoir evaporation. Natural salinity sources – saline springs, eroding salt-laden geologic formations, and runoff – still account for about half of the salt loading to the river. Consumptive water use for agricultural irrigation concentrates the naturally- occurring salts in the Colorado River water, these salts are leached from the root zone to maintain crop productivity, and the salts reenter the river as agricultural drainage water. Reservoir evaporation represents a much smaller cause of river salinity and most programs to reduce the salinity of the Colorado River have focused on agriculture; these include the lining of irrigation canals, irrigation efficiency improvements, and removing areas with poor drainage from production. Salt loading to the Colorado River has been reduced because of these efforts, but more work will be required to meet salinity reduction targets. Introduction The Colorado River is one of the most important rivers in the Western United States: it provides water for approximately 40 million people and irrigation water for 5.5 million acres of land, both inside and outside the Colorado River Basin (CRBSCF, 2014). -

Utah's Mighty Five from Salt Lake City

Utah’s Mighty Five from Salt Lake City Utah’s Mighty Five from Salt Lake City (8 days) Explore five breathtaking national parks: Arches, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, Bryce Canyon & Zion, also known as Utah's Mighty 5. You’ll get a chance to explore them all on this 8-day guided tour in southern Utah. Join a small group of no more than 14 guests and a private guide on this adventure. Hiking, scenic viewpoints, local eateries, hidden gems, and other fantastic experiences await! Dates October 03 - October 10, 2021 October 10 - October 17, 2021 October 17 - October 24, 2021 October 24 - October 31, 2021 October 31 - November 07, 2021 November 07 - November 14, 2021 November 14 - November 21, 2021 November 21 - November 28, 2021 November 28 - December 05, 2021 December 05 - December 12, 2021 December 12 - December 19, 2021 December 19 - December 26, 2021 December 26 - January 02, 2022 Highlights Small Group Tour 5 National Parks Salt Lake City Hiking Photography Beautiful Scenery Professional Tour Guide Comfortable Transportation 7 Nights Hotel Accommodations 7 Breakfasts, 6 Lunches, 2 Dinners Park Entrance Fees Taxes & Fees Itinerary Day 1: Arrival in Salt Lake City, Utah 1 / 3 Utah’s Mighty Five from Salt Lake City Arrive at the Salt Lake Airport and transfer to the hotel on own by hotel shuttle. The rest of the day is free to explore on your own. Day 2: Canyonlands National Park Depart Salt Lake City, UT at 7:00 am and travel to Canyonlands National Park. Hike to Mesa Arch for an up-close view of one of the most photographed arches in the Southwestern US. -

Townsendia Condensata Parry Ex Gray Var. Anomala (Heiser) Dorn (Cushion Townsend Daisy): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Townsendia condensata Parry ex Gray var. anomala (Heiser) Dorn (cushion Townsend daisy): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project May 9, 2006 Hollis Marriott and Jennifer C. Lyman, Ph.D. Garcia and Associates 7550 Shedhorn Drive Bozeman, MT 59718 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Marriott, H. and J.C. Lyman. (2006, May 9). Townsendia condensata Parry ex Gray var. anomala (Heiser) Dorn (cushion Townsend daisy): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/townsendiacondensatavaranomala.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to several of our colleagues who have authored thorough and clearly-written technical conservation assessments, providing us with excellent examples to follow, including Bonnie Heidel (Wyoming Natural Diversity Database [WYNDD]), Joy Handley (WYNDD), Denise Culver (Colorado Natural Heritage Program), and Juanita Ladyman (JnJ Associates LLC). Beth Burkhart, Kathy Roche, and Richard Vacirca of the Species Conservation Project of the Rocky Mountain Region, USDA Forest Service, gave useful feedback on meeting the goals of the project. Field botanists Kevin and Amy Taylor, Walt Fertig, Bob Dorn, and Erwin Evert generously shared insights on the distribution, habitat requirements, and potential threats for Townsendia condensata var. anomala. Kent Houston of the Shoshone National Forest provided information regarding its conservation status and management issues. Bonnie Heidel and Tessa Dutcher (WYNDD) once again provided much needed information in a timely fashion. We thank Curator Ron Hartman and Manager Ernie Nelson of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, University of Wyoming, for their assistance and for continued access to their fine facilities. -

EVALUATION REPORT Areas of Critical Environmental Concern Richfield Resource Management Plan

EVALUATION REPORT Areas of Critical Environmental Concern Richfield Resource Management Plan Dirty Devil and Henry Mountains Potential ACECs Richfield Field Office Bureau of Land Management January 2005 Evaluation Report Richfield Field Office EVALUATION REPORT—AREAS OF CRITICAL ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERN—RICHFIELD RMP/DEIS1 BACKGROUND ...........................................................................................................................................................1 The Law: FLPMA................................................................................................................................................1 The Regulation: 43 CFR 1610.7-2 .......................................................................................................................1 The Policy: BLM Manual 1613 ...........................................................................................................................1 EVALUATION PROCESS ..............................................................................................................................................2 Existing ACECs ...................................................................................................................................................2 ACEC Nominations .............................................................................................................................................2 Potential ACECs ..................................................................................................................................................6 -

West Colorado River Plan

Section 9 - West Colorado River Basin Water Planning and Development 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Background 9-1 9.3 Water Resources Problems 9-7 9.4 Water Resources Demands and Needs 9-7 9.5 Water Development and Management Alternatives 9-13 9.6 Projected Water Depletions 9-18 9.7 Policy Issues and Recommendations 9-19 Figures 9-1 Price-San Rafael Salinity Control Project Map 9-6 9-2 Wilderness Lands 9-11 9-3 Potential Reservoir Sites 9-16 9-4 Gunnison Butte Mutual Irrigation Project 9-20 9-5 Bryce Valley 9-22 Tables 9-1 Board of Water Resources Development Projects 9-3 9-2 Salinity Control Project Approved Costs 9-7 9-3 Wilderness Lands 9-8 9-4 Current and Projected Culinary Water Use 9-12 9-5 Current and Projected Secondary Water Use 9-12 9-6 Current and Projected Agricultural Water Use 9-13 9-7 Summary of Current and Projected Water Demands 9-14 9-8 Historical Reservoir Site Investigations 9-17 Section 9 West Colorado River Basin - Utah State Water Plan Water Planning and Development 9.1 Introduction The coordination and cooperation of all This section describes the major existing water development projects and proposed water planning water-related government agencies, and development activities in the West Colorado local organizations and individual River Basin. The existing water supplies are vital to water users will be required as the the existence of the local communities while also basin tries to meet its future water providing aesthetic and environmental values. -

Floating the Dirty Devil River

The best water levels and time Wilderness Study Areas (WSA) of year to float the Dirty Devil The Dirty Devil River corridor travels through two The biggest dilemma one faces when planning BLM Wilderness Study Areas, the Dirty Devil KNOW a float trip down the Dirty Devil is timing a WSA and the Fiddler Butte WSA. These WSA’s trip when flows are sufficient for floating. On have been designated as such to preserve their wil- BEFORE average, March and April are the only months derness characteristics including naturalness, soli- YOU GO: that the river is potentially floatable. Most tude, and primitive recreation. Please recreate in a people do it in May or June because of warm- manner that retains these characteristics. Floating the ing temperatures. It is recommended to use a hard walled or inflatable kayak when flows Dirty Devil are 100 cfs or higher. It can be done with “Leave-no-Trace” River flows as low as 65 cfs if you are willing to Proper outdoor ethics are expected of all visitors. drag your boat for the first few days. Motor- These include using a portable toilet when camping ized crafts are not allowed on this stretch of near a vehicle, using designated campgrounds The name "Dirty Devil" tells it river. when available, removing or burying human waste all. John Wesley Powell passed in the back country, carrying out toilet paper, using by the mouth of this stream on Another essential consideration for all visitors camp stoves in the backcountry, never cutting or his historic exploration of the is flash flood potential. -

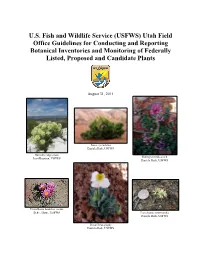

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Utah Field Office Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Botanical Inventories and Monit

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Utah Field Office Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Botanical Inventories and Monitoring of Federally Listed, Proposed and Candidate Plants August 31, 2011 Jones cycladenia Daniela Roth, USFWS Barneby ridge-cress Holmgren milk-vetch Jessi Brunson, USFWS Daniela Roth, USFWS Uinta Basin hookless cactus Bekee Hotze, USFWS Last chance townsendia Daniela Roth, USFWS Dwarf bear-poppy Daniela Roth, USFWS INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE These guidelines were developed by the USFWS Utah Field Office to clarify our office’s minimum standards for botanical surveys for sensitive (federally listed, proposed and candidate) plant species (collectively referred to throughout this document as “target species”). Although developed with considerable input from various partners (agency and non-governmental personnel), these guidelines are solely intended to represent the recommendations of the USFWS Utah Field Office and should not be assumed to satisfy the expectations of any other entity. These guidelines are intended to strengthen the quality of information used by the USFWS in assessing the status, trends, and vulnerability of target species to a wide array of factors and known threats. We also intend that these guidelines will be helpful to those who conduct and fund surveys by providing up-front guidance regarding our expectations for survey protocols and data reporting. These are intended as general guidelines establishing minimum criteria; the USFWS Utah Field Office reserves the right to establish additional standards on a case-by-case basis. Note: The Vernal Field Office of the BLM requires specific qualifications for conducing botanical field work in their jurisdiction; nothing in this document should be interpreted as replacing requirements in place by that (or any other) agency. -

Emery County Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018

Emery County Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 Emery County Page 1 Emery County Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 Table of Contents Emery County 4 PDM Project Quick Reference 5 PDM Introduction 7 Demographics and Population Growth 13 Economy 15 Transportation and Commuting Trends 16 Land Use and Development Trends 17 Risk Assessment (Working Group) 19 Critical Facilities 20 Natural Hazards Profiles 28 Dam Failures 37 Flood 45 Landslides 48 Wildland Fires 53 Problem Soils 55 Infestation 58 Severe Weather 59 Earthquake 64 Drought Hazard History 68 Mitigation Goals, Objectives and Actions 77 Drought 77 Flood 80 Wildland Fires 92 Severe Weather 93 Earthquake 95 Landslides 96 Dam Failure 97 Problem Soils 99 Infestation 100 Hazus Report Appendix 1 Plan Maintenance, Evaluation and Implementation Appendix 2 PDM Planning Process Appendix 3 General Mitigation Strategies Appendix 4 Environmental Considerations Appendix 5 Research Sources Appendix 6 Emery County Community Wildfire Preparedness Plan (CWPP) Appendix 7 Emery County Page 2 Emery County Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 Utah Information Resource Guide Emery County Page 3 Emery County Pre-Disaster Hazard Mitigation Plan 2018 Emery County Emery County is located where the desert meets the mountains in Southeastern Utah. It encompasses 4,452 square miles making it Utah’s seventh largest county. On the western side of the County is the Wasatch Plateau, which is the major water supply for the County. The San Rafael Swell dominates the County’s center with its rugged reefs, “castles”, and gorges. East of the San Rafael Swell is the Green River Desert, an arid district which has been historically important to ranching operations located in the lower San Rafael Valley. -

Quantifying the Base Flow of the Colorado River: Its Importance in Sustaining Perennial Flow in Northern Arizona And

1 * This paper is under review for publication in Hydrogeology Journal as well as a chapter in my soon to be published 2 master’s thesis. 3 4 Quantifying the base flow of the Colorado River: its importance in sustaining perennial flow in northern Arizona and 5 southern Utah 6 7 Riley K. Swanson1* 8 Abraham E. Springer1 9 David K. Kreamer2 10 Benjamin W. Tobin3 11 Denielle M. Perry1 12 13 1. School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, US 14 email: [email protected] 15 2. Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, US 16 3. Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, US 17 *corresponding author 18 19 Abstract 20 Water in the Colorado River is known to be a highly over-allocated resource, yet decision makers fail to consider, in 21 their management efforts, one of the most important contributions to the existing water in the river, groundwater. This 22 failure may result from the contrasting results of base flow studies conducted on the amount of streamflow into the 23 Colorado River sourced from groundwater. Some studies rule out the significance of groundwater contribution, while 24 other studies show groundwater contributing the majority flow to the river. This study uses new and extant 1 25 instrumented data (not indirect methods) to quantify the base flow contribution to surface flow and highlight the 26 overlooked, substantial portion of groundwater. Ten remote sub-basins of the Colorado Plateau in southern Utah and 27 northern Arizona were examined in detail. -

Appendix L—Acec Evaluations for the Price Resource Management Plan

Proposed RMP/Final EIS Appendix L APPENDIX L—ACEC EVALUATIONS FOR THE PRICE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN INTRODUCTION Section 202(c)(3) of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) requires that priority be given to the designation and protection of areas of critical environmental concern (ACEC). FLPMA Section 103 (a) defines ACECs as public lands for which special management attention is required (when such areas are developed or used or when no development is required) to protect and prevent irreparable damage to important historic, cultural, or scenic values; fish and wildlife resources; or other natural systems or processes or to protect life and safety from natural hazards. CURRENTLY DESIGNATED ACECS BROUGHT FORWARD INTO THE PRICE RMP FROM THE SAN RAFAEL RMP In its Notice of Intent (NOI) to prepare this Resource Management Plan (RMP) (Federal Register, Volume 66, No. 216, November 7, 2001, Notice of Intent, Environmental Impact Statement, Price Resource Management Plan, Utah), BLM identified the 13 existing ACECs created in the San Rafael RMP of 1991. The NOI explained BLM’s intention to bring these ACECs forward into the Price Field Office (PFO) RMP. A scoping report was prepared in May 2002 to summarize the public and agency comments received in response to the NOI. The few comments that were received were supportive of continued management as ACECs. The ACEC Manual (BLM Manual 1613, September 29, 1988) states, “Normally, the relevance and importance of resource or hazards associated with an existing ACEC are reevaluated only when new information or changed circumstances or the results of monitoring establish a need.” The following discussion is a brief review of the existing ACECs created by the San Rafael RMP of 1991 and discussed in the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).