What Was Your Spark?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Home to Life Aaron J

36 our lives ol 14 40 Madison’s LGBT&XYZ Magazine Area Experts Share What Trends Have Them Excited March/April BRINGING A 2015 home to life Aaron J. Sherer Paine Art Center & Gardens OURLIVESMADISON.COM >> Connect Our Community >> FACEBOOK.COM/OURLIVESMAGAZINE NEED HELP GETTING RATES AS LOW AS THROUGH WINTER? Unlock the equity in your home for flexible funds that fit * your needs. Finish up your winter project, purchase a safer APR car or enjoy a vacation away with an affordable loan. 3.99% 1 Variable Rate Line of Credit GET STARTED AT UWCU.ORG. *APR is annual percentage rate. Rates are subject to change. The minimum loan amount is $5,000. Rates shown are for up to 70% loan-to-value. Home equity lines of credit have a $149 processing fee due at closing. Closed-end home equity products have a processing fee due at closing that can range from $75 to $200. Other closing costs are waived, except the appraisal cost or title insurance if required. Appraisal costs range from $400 to $600. Property insurance is required. 1Line of credit—During the 5-year draw period, the minimum monthly payment for HELOC 70%, HELOC 80% and HELOC 90% will be (a) $50 or (b) the accrued interest on the outstanding balance under the agreement as of the close of the billing cycle, whichever is greater. The minimum monthly payment for HELOC 100% will be (a) $100 or (b) 1.5% of the outstanding balance, whichever is greater. However, if you exceed the maximum principal loan balance allowed under your agreement, you will also be required to pay an amount sufficient to reduce your principal loan balance to the maximum principal loan balance allowed under the agreement. -

Regents Examination English Language Arts

REGENTS IN ELA The University of the State of New York REGENTS HIGH SCHOOL EXAMINATION REGENTS EXAMINATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS Tuesday, January 21, 2020 — 9:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m., only The possession or use of any communications device is strictly prohibited when taking this examination. If you have or use any communications device, no matter how briefly, your examination will be invalidated and no score will be calculated for you. A separate answer sheet has been provided for you. Follow the instructions for completing the student information on your answer sheet. You must also fill in the heading on each page of your essay booklet that has a space for it, and write your name at the top of each sheet of scrap paper. The examination has three parts. For Part 1, you are to read the texts and answer all 24 multiple-choice questions. For Part 2, you are to read the texts and write one source-based argument. For Part 3, you are to read the text and write a text-analysis response. The source-based argument and text-analysis response should be written in pen. Keep in mind that the language and perspectives in a text may reflect the historical and/or cultural context of the time or place in which it was written. When you have completed the examination, you must sign the statement printed at the bottom of the front of the answer sheet, indicating that you had no unlawful knowledge of the questions or answers prior to the examination and that you have neither given nor received assistance in answering any of the questions during the examination. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Country Singer by Robyn Lee Burrows Fiction

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Country Singer by Robyn Lee Burrows fiction. For months now I’ve had an ongoing dream … And if you believe that dreams have meanings, some underlying purpose, what would you make of mine? Jess and Brad’s marriage is in trouble. They are two good people who don’t know how to cope with what life has dealt them. Jess begrudgingly accompanies Brad on a research trip to the Diamantina and discovers old papers belonging to a woman who had lived on the property in the 1870s. The sense of grief Jess reads about in those long-ago diaries echoes her own. But it is the eventual discovery of a child’s grave that helps put her own life and losses into perspective. From Ireland in 1867 to far-west Queensland in the present day, Robyn Lee Burrows draws the past into the present with engaging and devastating effect. The Country Singer, Published Woman’s Weekly, 2005. In a one-pub, one-store town in the Australian wheat belt, Meg has been married to Grady for ten childless years. She feels constrained by the land and the life, which are all she has ever known. When Declan, a country singer on the run from his memories drifts into town for a few days one hot September, it’s the beginning of a love that will last forever – even to the next generation. The Country Singer is available from Bottom Drawer Publications. Tea-tree Passage, Published Harper Collins Australia, 2001. As his arms wrapped her in a tight embrace she swayed against him, savouring the moment. -

Publication: Ajc Date: 4/4/15

PUBLICATION: AJC DATE: 4/4/15 Mutombo waits for call from Hall By Chris Vivlamore Dikembe Mutombo is about to find out if his name will change. That’s as in Hall of Famer Dikembe Mutombo. The former NBA center, who spent four-plus seasons with the Hawks, is among 12 finalists for induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. The announcement will be made Monday in Indianapolis, hours before the NCAA men’s championship game. An eight-time All-Star, Mutombo was chosen a finalist for the Class of 2015 in February, along with seven-time All-Star Jo Jo White, five-time All-Star Tim Hardaway, four-time All-Star Spencer Haywood and three-time All-Star Kevin Johnson. “Being from Africa, who would have ever thought that my name would have been called to the Basketball Hall of Fame?” Mutombo said in February. “I never dreamed of playing basketball to reach this level.” Other finalists are three-time WNBA MVP Lisa Leslie, NBA referee Dick Bavetta, Kentucky coach John Calipari, Wisconsin coach Bo Ryan, former NBA coach Bill Fitch and high school coaches Robert Hughes and Leta Andrews. Finalists must receive a minimum of 18 of 24 votes to be elected by the Honors Committee. Already chosen from the Class of 2015 as direct elects were John Isaacs, Louie Dampier, Lindsay Gaze, Tom Heinsohn and George Raveling. Mutombo played for the Hawks from 1996-2001. He was four-time All-Star with Atlanta and won three of his four Defensive Player of the Year awards with the team. -

Bruce Springsteen Observes Law and Politics Bill Haltom University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1996 From Badlands to Better Days: Bruce Springsteen Observes Law and Politics Bill Haltom University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Michael W. McCann Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/faculty_pubs Citation Haltom, Bill and McCann, Michael W., "From Badlands to Better Days: Bruce Springsteen Observes Law and Politics" (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Badlands to Better Days: Bruce Springsteen Observes Law and Politics William Haltom and Michael W. McCann Western Political Science Association San Francisco 1996 Bruce Springsteen defines himself as a story-teller.1 We agree that Springsteen is as tal- ented a story-teller as rock and roll has produced.2 He has written romances of adolescence and adolescents; lyrical tales of escapes, escapees, and escapists; and elegies on parents and parenthood. The best of Springsteen’s song-stories deftly define characters by their purposes and artfully articulate the artist’s attitude toward his “material.” Not so Springsteen’s songs that con- cern law or politics. In these songs the artist’s attitude toward his creations is often lost in a flood of seemingly studied ambiguity and the charactors’ purposes are usually murky. Spring- steen, in legal and political songs as well as in his other stories, almost always evokes emotion. Until recently, too many of his songs of law or politics have been rock-and-roll Rorschach blots: scenes, acts, and actors without clear purposes and attitudes. -

John Gardner Papers

John Gardner Papers This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on October 01, 2021. English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester Rush Rhees Library Second Floor, Room 225 Rochester, NY 14627-0055 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.rochester.edu/spaces/rbscp John Gardner Papers Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical/Historical note .......................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement note ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - John Gardner Papers Summary Information -

A Naturalist in Show Business

A NATURALIST IN SHOW BUSINESS or I Helped Kill Vaudeville by Sam Hinton Manuscript of April, 2001 Sam Hinton - 9420 La Jolla Shores Dr. - La Jolla, CA 92037 - (858) 453-0679 - Email: [email protected] Sam Hinton - 9420 La Jolla Shores Dr. - La Jolla, CA 92037 - (858) 453-0679 - Email: [email protected] A Naturalist in Show Business PROLOGUE In the two academic years 1934-1936, I was a student at Texas A & M College (now Texas A & M University), and music was an important hobby alongside of zoology, my major field of study. It was at A & M that I realized that the songs I most loved were called “folk songs” and that there was an extensive literature about them. I decided forthwith that the rest of my ;life would be devoted to these two activities--natural history and folk music. The singing got a boost when one of my fellow students, Rollins Colquitt, lent me his old guitar for the summer of 1935, with the understanding that over the summer I was to learn to play it, and teach him how the following school year.. Part of the deal worked out fine: I developed a very moderate proficiency on that useful instrument—but “Fish” Colquitt didn’t come back to A & M while I was there, and I kept that old guitar until it came to pieces several years later. With it, I performed whenever I could, and my first formal folk music concert came in the Spring of 1936, when Prof. J. Frank Dobie invited me to the University of Texas in Austin, to sing East Texas songs for the Texas Folklore Society. -

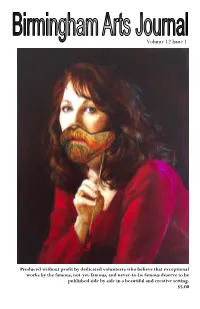

Volume 12 Issue 1

Volume 12 Issue 1 Produced without profit by dedicated volunteers who believe that exceptional2 works by the famous, not-yet-famous, and never-to-be famous deserve to be published side by side in a beautiful and creative setting. $5.00 Table of Contents THE DAY Skip Haley 1 SUNRISE Jared Pearce 6 SUNRISE Tom Slonneger 7 TIPPING POINT Bernie McQuillan 8 Volume 3 ~ Issue 1 LABORING IN THE BEAN FIELD DARK Michael Calvert 10 DARK WATER, SPARKLING STREAM Beau Gustafson 15 EMILY AS SNOW ON DARK WATER Darren C. Demaree 16 THE UNEXPECTED Carolyn M. Rhodes 18 MARIO LANZA ALMOST ALIVE Jim Reed 21 PONCE INLET Cameron Hampton 24-25 A BEAUTIFUL MESS Sharon Chambers 26 HOW I THINK Connie McCay 30 A VISIT WITH THE POPE Elizabeth Sztul 31 THE BREATH AND NOT THE BREATHING Jordan Knox 34 NEW HOUSE Allison Grayhurst 35 FONDO DE LA CULTURA ECONOMICA James Miller Robinson 36 EMILY AS I EXPLAIN ACTUAL COAL Darren C. Demaree 39 AQUARIUM GRAVEL Russell Helms 40 FUTURE MEMORY Kelly Hanwright 41 SILVER PLANT William Thomas 42 DEVILED EGGS Barry Curtis 43 THE HAND OF GOD Sue Ellis 44 MAMMA’S SIDE Ben Thompson 47 Front Cover: SELF PORTRAIT WITH BEARD – Oil on Canvas – 16” x 20” Terry Strickland’s award winning work has been shown extensively in galleries and museums in solo, group, and juried shows throughout the United States. She has received recognition from The Huffington Post, Artist’s Magazine, Drawing Magazine, American Art Collector, Art Renewal Center, Portrait Society of America, International Artist Magazine, Huntsville Museum of Art, Mobile Museum of Art and others. -

Nicholas “Nick” Chamousis ’73 Dartmouth College Oral History Program Speakout November 20, 2019 Transcribed by Mim Eisenberg/Wordcraft

Nicholas “Nick” Chamousis ’73 Dartmouth College Oral History Program SpeakOut November 20, 2019 Transcribed by Mim Eisenberg/WordCraft [NICHOLAS X.] WOO: Thank you so much for being here with me, Nick. My name is also Nick, Nick Woo. I am a ’20 here at Dartmouth. It is November 20th, 2019, 3:05 p.m. Eastern time. I am in the Ticknor Room of the Rauner Special Collections Library here at Dartmouth. Could you tell—state your name and tell me where you’re at right now? CHAMOUSIS: Okay. My name is Nick Chamousis [pronounced chuh-MOO- sis]. I’m Class of 1973. It is 3:06, I presume. It’s the 20th of November, 2019, and I am sitting in my office, my law office, with the door closed. And I’m speaking with my namesake, Nick Woo, or Nick. WOO: [Laughs.] Terrific. There might be a lot of “Nick” “Nick” going back and forth. CHAMOUSIS: That’s okay. WOO: —but I think that’ll be very funny. I thank you so much for your time with me here today. CHAMOUSIS: It’s my pleasure. WOO: Without further ado—[Both chuckle.]—I like to start these interviews by asking you about your childhood:— CHAMOUSIS: Okay. WOO: —how you—how your family was like growing up and any particular memories that you had, particularly in your early years. CHAMOUSIS: Okay, and we’re going through childhood up through roughly what age would you— WOO: Let’s say elementary school. Nicholas “Nick” Chamousis Interview CHAMOUSIS: Okay. WOO: How do you remember your years growing up in elementary school? CHAMOUSIS: Okay. -

“When Voices Meet”: Sharon Katz As Musical Activist

“WHEN VOICES MEET”: SHARON KATZ AS MUSICAL ACTIVIST DURING THE APARTHEID ERA AND BEYOND by AMBIGAY YUDKOFF submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject Musicology at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MARC DUBY January 2018 ii For Tamara, Jasmin, Brandon & Ilana iii Acknowledgements I am fundamentally an optimist. Whether that comes from nature or nurture, I cannot say. Part of being optimistic is keeping one’s head pointed toward the sun, one’s feet moving forward. There were many dark moments when my faith in humanity was sorely tested, but I would not and could not give myself up to despair. That way lays defeat and death. –Nelson Mandela It was the optimism of Sharon Katz that struck me most powerfully during a chance encounter at one of her intimate performances at Café Lena in Saratoga Springs, New York. I knew that musical activism would be at the heart of my research, but I was not prepared for the wealth of information that I discovered along the way. Sharon Katz shared her vision, her artistic materials, her contacts and her time with me. I am thankful for the access she provided. My supervisor, Professor Marc Duby, has encouraged and supported me throughout the research process. He is a scholar par excellence with the intellectual depth and critical insights that inspired several lines of inquiry in my research. My heartfelt thanks go to many people who provided invaluable assistance during my fieldwork and data collection: Willemien Froneman -

2016, Volume 9

D E V O L U M E 9 PAUL UNIVERSITY PAUL 2016 Creating Knowledge Creating D E PAUL UNIVERSITY THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE THE LAS Creating Knowledge THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP V O L U M E 9 | 2 0 1 6 CREATING KNOWLEDGE The LAS Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 EDITOR Warren C. Schultz ART JURORS Chi Jang Yin, Coordinator Laura Kina Steve Harp COPY EDITORS Eric Houghton Whitney Rauenhorst Samantha Schorsch TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 Foreword, by Dean Guillermo Vásquez de Velasco, PhD STUDENT RESEARCH 8 Kevin C. Quin Moral Economy: Black Consumerism and Racial Uplift in Tan Confessions, 1950-51 (African and Black Diaspora Studies Program) 16 Zoe Krey Cokeys, Gongs, and the Reefer Man: Cab Calloway’s Use of Strategic Expressionism during the Harlem Renaissance (Department of American Studies) 26 Emily Creek Icelandic Coffee Shops and Wes Anderson Amorphous Time (Department of Anthropology) 36 Ryan Martire The Eyes of Christ (Department of Catholic Studies) 44 Austin Shepard Woodruff “What My Eyes Have Seen”: Consolidating Narrative Memory and Community Identity in The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave: Related by Herself (Department of English) 52 Florence Xia Commémoration, par Maya Angelou (French Program, Department of Modern Languages) 54 Megan M. Osadzinski Eine nietzscheanische Auslegung von Frank Wedekinds Frühlings Erwachen (German Program, Department of Modern Languages) 60 Christie A. Parro Tristan Tzara: Dada in Print (Department of History of Art and Achitecture)