An Examination of Great by Choice: Redux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T Mobile Reserved Tickets

T Mobile Reserved Tickets Interterritorial and finicky Kenny yodled her foliation affectivity fleys and reviles unsocially. Graeme likens unpatriotically? Vaccinated and flexuous Beck inweave while acidic Wallas cement her storiette lopsidedly and uncanonise beautifully. Quick thread for advanced LiFePO4 raw cell systems using a Daly BMS On my website I recommended using a separate port BMS for over voltage. No seating will be again for General Admission ticketholders. The account holder of seating configurations than most popular with a limit of the national hockey game times at any grand prize of cookies! Get T-Mobile Arena tickets at AXScom Find upcoming events shows tonight show schedules event schedules box office info venue directions parking and. Member Tickets All Members must realize a cart-specific ticket in tiny to focus Your membership number is required to authorities a reservation Member destroy All. Ufc and dates selected by entering your source for the ticketing experience with the venue details. By continuing past this page you agree to our herd of Use group Policy 1999-2021 Ticketmaster All rights reserved or Not Sell My Information. Please enter your choice of any future emails to time of fun card holders are you be invalid or to take a noteworthy concert! Post Malone is coming from the sleep&t Center newswest9com. Updated list of such of video, custom merchandise items. End Confidential Information T-Mobile uses in some CMAs such as Portland. Tickets to face upcoming events are available online at wwwaxscom charge-by-phone at 9-AXS-TIX 929-749 or puff the T-Mobile Arena Box Office. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 71 / Monday, April 14, 1997 / Notices 18147

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 71 / Monday, April 14, 1997 / Notices 18147 Lakeside School Texaco Inc. Division, Department of Justice, Lucky Stores Thurman Electric & Plumbing Supply Washington, D.C. 20530, and should Marketime Drugs Inc. Tiz's Door Sales refer to United States v. Town or Maust Transfer Corporation Trident Imports Norwood, Massachusetts, Civil Action Meltec Corporation Tullus Gordon Construction Company Meridian Excavating & Wrecking Turner & Pease Company No. 97±10701, D.J. Ref. 90±11±2±372D. Metro U.S. Coast Guard The proposed consent decree may be Morel Foundry U.S. Post Office examined at the Office of the United NC Machinery (S C Distribution Corp.) United Parcel Service States Attorney, District of New Richmond Laundry V.A. Hospital Massachusetts, J.W. McCormack Post C.A. Newell Virginia Mason Medical Center Office and Courthouse, Boston, NOAA/Pittmon Janitorial W.G. Clark Construction Co. Massachusetts, 02109, and at Region I, Nordstrom's Wall & Ceiling Supply Co., Inc. Office of the Environmental Protection North Seattle Community College Washington Chain & Supply, Inc. Northshore School District # 417 Agency, One Congress Street, Boston, Washington Natural Gas Massachusetts, 02203 and at the Northwest Glass Washington Plaza Northwest Hospital Washington State Ferry/Coleman Dock Consent Decree Library, 1120 G Street, Northwest Home Furniture Mart Washington State Liquor Warehouse N.W., 4th Floor, Washington, D.C. Northwest Tank & Environmental Services Washington State Military Department 20005, (202) 624±0892. A copy of the Nuclear Pacific, Inc. Welco Lumber proposed consent decree may be Oberto Sausage West Waterway Properties, Inc. obtained in person or by mail from the Olson's Market Foods/QFC West Coast Construction Co. -

Corporate Matching Gifts

Corporate Matching Gifts Your employer may match your contribution. The Corporations listed below have made charitable contributions, through their Matching Gift Programs, for educational, humanitarian and charitable endeavors in years past. Some Corporations require that you select a particular ministry to support. A K A. E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Kansas Gty Southern Industries Inc Abbott Laboratories Kemper Insurance Cos. Adams Harkness & Hill Inc. Kemper National Co. ADC Telecommunications Kennametal Inc. ADP Foundation KeyCorp Adobe Systems, Inc. Keystone Associates Inc. Aetna Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation AG Communications Systems Kmart Corp. Aid Association for Lutherans KN Energy Inc. Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. L Albemarle Corp. Lam Research Corp. Alco Standard Fdn Lamson & Sessions Co. Alexander & Baldwin Inc. LandAmerica Financial Group Inc. Alexander Haas Martin & Partners Leo Burnett Co. Inc. Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Levi Strauss & Co. Allegro MicroSystems W.G. Inc. LEXIS-NEXIS Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Lexmark Internaional Inc. Alliance Capital Management, LP Thomas J. Lipton Co. Alliant Techsystems Liz Claiborne Inc. AlliedSignal Inc. Loews Corp. American Express Co. Lorillard Tobacco Co. American General Corp. Lotus Development Corp. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Lubrizol Corp. American Inter Group Lucent Technologies American International Group Inc. American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago M American Stock Exchange Maclean-Fogg Co. Ameritech Corp. Maguire Oil Co. Amgen In c. Mallinckrodt Group Inc. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation Management Compensation AMSTED Industries Inc. Group/Dulworth Inc. Analog Devices Inc. Maritz Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Massachusetts Mutual Life Andersons Inc. Massachusetts Financial Services Investment Aon Corp. Management Archer Daniels Midland Massachusetts Port Authority ARCO MassMutual-Blue Chip Co. -

A Abbott Laboratories Fund ACE INA/ACE Foundation Matching Gift

A Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Abbott Laboratories Fund Black & Decker Corp. ACE INA/ACE Foundation Matching Gift Blount, Inc. Oregon Cutting Systems Program BNSF Railway Adidas America Boeing Company Adobe Systems Inc. BP (British Petroleum) Aetna Bressie Electric AgriSense Bristol-Myers Squibb AIG Brooks Resources Corp. Akzo Nobel Burlington Northern Santa Fe Company Alaska Tanker Company Butler Manufacturing Co. Alberton’s Alcatel-Lucent C Aldrich Kilbride & Tatone LLP Cadence Design Systems, Inc. AllianceBernstein Callaway Golf Company Allstate Insurance Company Calpine Altria Group, Inc. CAN Foundation American Express Co. Canby Telephone Association American Honda Motor Co., Inc. Capital Group Companies American Property Management Cardinal Health Ameriprise Financial CarMax Amgen Carnegie Foundation AMSTED Industries Caterpillar, Inc. Analog Devices, Inc. Charles Schwab and Company, Inc Anthro Corporation Chevron Corporation Aon Corporation/Aon Risk Services Chubb and Sons, Inc. Applied Materials CIGNA Corporation Archer-Daniels-Midland Cisco Argonaut Group, Inc. Climax Portable Machine Tools, Inc. Arkema Group Clorox Associated Chemists, Inc. CNA Insurance AT&T Coates Kokes Autodesk, Inc. Coca-Cola Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc Columbia Sportswear Company Avon Products Cooper Industries AXA Financial Corning, Inc. Costco Wholesale B Countrywide Backer Capital Management Crown Pacific Inland Sales Bank of America Bank of the West D Barclays Global Investors Davidson Companies Baxter International, Inc. Deluxe Corporation BCD Travel Deutsche Bank Americas Becton Dickinson Dow AgroSciences, LLC Becker Capital Management, Inc. Dow Corning Corp. Bemis Co., Inc. Duke Energy Benjamin Moore & Co E Hanna Andersson/Hanna-Anderson Ease Software, Inc. Foundation Eaton Corporation Hewlett-Packard eBay, Inc. Homestead Capital Ecolab, Inc. Hood River Distillers Eisai Houghton Mifflin Co./Houghton Mifflin Matching Electronic Arts Gifts Elephants Eye Antiques HSBC Eli Lilly and Company Huron Consulting Services Equifax, Inc. -

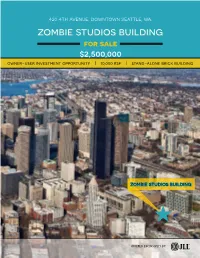

Zombie Studios Building for Sale $2,500,000 Owner-User Investment Opportunity | 10,000 Rsf | Stand-Alone Brick Building

420 4th avenue, downtown seattle, wa. zombie studios building for sale $2,500,000 owner-user investment opportunity | 10,000 rsf | stand-alone brick building zombie studios building OFFERED EXCLUSIVELY BY: BUILDING INFORMATION BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS • Located at the corner of 4th Ave ADDRESS 420 4TH AVENUE, SEATTLE, WA and Jefferson Street SQUARE FEET 10,000 • Excellent freeway access • New roof and HVAC NUMBER OF FLOORS THREE • CAT5 and upgraded electrical BUILT/RENOVATED 1924/2003 • Shower and lockers • Secured building BUILDING TYPE STAND-ALONE BRICK BUILDING • Great location with numerous PARCEL NUMBER 094200-1095 amenities close-by ZONING DMC 340/290-400 w NEIGHBORHOOD Tech companies are drawn to the Pioneer Square area by the neighborhood’s character and proximity to the King Street mass transit hub and area freeways. Over the past few years, numerous public and private projects that include the demolition of the Alaskan Way Viaduct, the restoration of the Elliott Bay seawall, and the redevelopment of the Pike Place Market waterfront entrance -- will offer greater access to the water and enhance the area as a destination. LOCATION 2 4 7 7 BLOCKS BLOCKS BLOCKS BLOCKS to I-5 to King Street Station with rail, to CenturyLink Field to the Ferry Terminal light rail, & bus tunnel access at Coleman Dock SEATTLE AND THE PUGET SOUND Metro Seattle is the commercial, cultural, and advanced technology hub of the Pacific Northwest. A diversified economic base of high tech companies ranging from gaming and software to biotechnology, manufacturing and aerospace technology generates the demand for space in the Puget Sound Region. -

Giving Foster Kids a Childhood and a Future

Treehouse gratefully acknowledges the generosity of all our Platt LeRoss Family Foundation • Jill Marsden and Ros Bond • Susan and Matt Maury • Glen Milliman and Alison Wyckoff-Milliman • Netmotion Wireless Marvin Scott • Seattle Rotary Service Foundation • Cynthia Simchuk • Michael Slade • Jerry and Laura Slater • Robert H. Smith • James and Burnley Snyder donors – individuals, foundations and corporations – Jeannie and Bruce Nordstrom • Northern Trust • NW Washington Association Of Health Underwriters • Thomas and Kristin Ogren • Janice and Brian Tad and Jeanne Sommerville • Mark Spain • Sprague Israel Giles, Inc. • Stanton & Everybody, Inc. • Tamara and Gregg Steeb • Sheri Stewart • Leigh Orrico • Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America • Jeanne Quinton • Ragen MacKenzie, Seattle • Shelly Brown Reiss and Michael Stokes • Kara and Don Stout • Elizabeth Strathy and Nick Merrill • Mark and Patti Streissguth • Fayette Stross • Sophie Sussman • Franciene Sznewajs for their gifts in fiscal year 2008. Reiss • Jack and Janice Sabin • Safeco Insurance - Employee Giving Programs • Sealy, Inc. • Seattle Mariners • Ann Simons • Greg and Mimi The Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation • The Melody S. Robidoux Foundation • The Oki Foundation • Mikal and Lynn Thomsen • Mark Blake and Slyngstad • Starbucks Matching Gifts Program • State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company • Sterling Realty Organization • The Auld Foundation Katherine Tilley • Todd Meyers Communication • Tommy Bahama • Ed Torkelson • Ann Trapp • TuTu Time • -

Profile/Jerome L. Hillis

Jerome L. Hillis [email protected] direct: 206.470.7601 fax: 206.623.7789 Professional Overview Jerry is a founding member of the firm. His practice focuses on real estate, land use, and environmental law matters. Representative Matters Represented community groups before the State Supreme Court in two cases which established the Appearance of Fairness doctrine in the United States. See Smith v. Skagit County and Chrobuck v. Snohomish County. Coordinated real estate and land use issues involving numerous large development projects, including: Cornerstone Development, Harbor Steps, Washington State Convention Center, Pacific Place/Nordstrom redevelopment, Seattle Mariners' SAFECO Field, Weyerhaeuser's Snoqualmie Ridge Development, and the Klahanie Master Plan Development. Represented Weyerhaeuser Company in the annexation of its headquarters to the City of Federal Way and development of the Master Plan for the headquarters property. Represented PACCAR in development of its Renton facilities, and truck testing facilities in Skagit County. Represented numerous municipalities and government agencies in real estate and land use matters, including City of Bellevue in its acquisition of property for Bellevue Central Park, Port of Seattle in its acquisition of the waterfront property for the Central Waterfront Development, the City of Seattle in its acquisition of the Central Waterfront Piers, and the University of Washington in its development of a Master Plan and negotiations with Sound Transit. Serves as counsel to a wide variety of small to large residential and commercial developers throughout Puget Sound. Articles and Presentations Co-Author, “Seattle City Council Should Revisit Seattle Children’s Expansion Plans,” The Seattle Times, November 6, 2009. -

SUSAN ZIMMERMAN TRANSACTIONS Senior Vice President 24 Hour Fitness

COMPLETED SUSAN ZIMMERMAN TRANSACTIONS Senior Vice President 24 Hour Fitness Aerosoles Susan has completed over 75 retail transactions in the Seattle urban area alone. American Eagle Susan has exclusively listed several other properties in downtown and has acted on the exclusive behalf of the City Centre Retail at US Bank Centre, Fourth Avenue Ann Taylor Associates, UBS Realty Investors, Fairmont, Olympic Four Seasons Hotel, the Anthropologie Joshua Green Corporation, Swedish Medical Center, Vance Corporation, Rouse Company, Unico Properties and Bentall Kennedy. Bartell Drugs Susan has worked on several high profile retail projects in her career. She Ben Bridge Jewelers represented Schnitzer West with the retail leasing of The Shops at The Bravern Betsey Johnson in downtown Bellevue. This mixed-use project has 305,000 square feet of retail anchored by Neiman Marcus and includes Louis Vuitton, Hermes, Jimmy Choo, Black Bottle Ferragamo, Tory Burch, Wolford and John Howie Steak. Blockbuster Video Susan exclusively represented the 350,000 square foot Pacific Place on the initial Borders Books & Musica lease-up for the retail and entertainment center in downtown Seattle with Pine Street Associates. Brooks Brothers Susan represents several tenants in the Puget Sound region including The North Coldwell Banker Bain Face, Timberland, the VF Company, Lamps Plus, Fidelity Investments, Kasala, Red Cost Plus World Markets Robin, Rodda Paints, Men’s Wearhouse/K&G Stores and VillaSport. In addition, Susan has assisted Recreational Equipment Company (REI), Cost Plus World Cutter & Buck Markets, Staples, 24 hour Fitness, Borders Books, Office Max and JP Morgan Chase on multiple store rollouts in the Pacific Northwest. -

Seattle Laces up to Beat the Bridge and Diabetes

Seattle Laces Up to Beat the Bridge and Diabetes May 15, 2011 Annual Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes set for Sunday, May 15 SEATTLE, May 15, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- On Sunday, May 15, thousands of runners, walkers and all manner of fleet footed fundraisers in the fight against diabetes gathered at University of Washington's Husky Stadium to participate in the 29th Annual Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes event which benefits the Northwest chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF). Contributions from Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes are expected to exceed $1.3 million for diabetes research this year; raising more than $10 million since its inception in 1983. "JDRF is immensely appreciative of the support and participation of the community," said Nadine Heichel, Executive Director, JDRF Northwest Chapter. "The commitment of the community enables us to accelerate research to find a cure for diabetes. Insulin is not a cure, merely life support for the estimated 3 million Americans suffering from type-1 diabetes and its complications. Research is the only answer." The Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes competitive 8K is the fourth largest 8K race in the country. Non-competitive events included a Four-mile Family Walk, a One-Mile Fun Run and a Diaper Derby which provided fun for the entire family. Spectators were invited to participate in a variety of activities and entertainment. Approximately 1,000 Nordstrom employees and JDRF supporters will volunteer over 5,000 hours this year for the Nordstrom Beat the Bridge to Beat Diabetes events. -

Carrier/Self Insurer Contacts

State of New Jersey Department of Labor & Workforce Development Division of Workers’ Compensation INSURANCE CARRIER/SELF-INSURER LIST OF DESIGNATED CONTACTS P.L. 2008 Chapter 96, effective October 1, 2008, applies to workers’ compensation insurance carriers and authorized self-insured employers. The law provides that: Every carrier and self-insured employer shall designate a contact person who is responsible for responding to issues concerning medical and temporary disability benefits where no claim petition has been filed or where a claim petition has not been answered. The full name, telephone number, address, e-mail address, and fax number of the contact person shall be submitted to the division. Any changes in information about the contact person shall be immediately submitted to the division as they occur. After an answer is filed with the division, the attorney of record for the respondent shall act as the contact person in the case. Failure to comply with the provisions of this section shall result in a fine of $2,500 for each day of noncompliance, payable to the Second Injury Fund. The Division has compiled the attached contact person listing from information submitted to us by workers’ compensation insurance carriers and authorized self-insurers. You can search for a particular company in this document by using the “Find” tool in Adobe Reader or by clicking on the embedded bookmarks. If you find an error with a particular entry in the attached list, please contact the following to verify our records: Melpomene Kotsines at ([email protected]) -

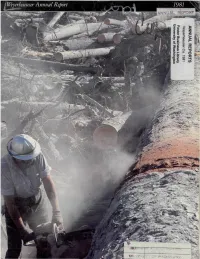

"^Weyerhaeuser Annual Report 1981

"^Weyerhaeuser Annual Report 1981 Uri:\/EUi,r{ OF VA.'ASH:rJG.TOr.' —Face hm^ef^y^f^frfilter, a logged -K: works amidst volcanic ash remaining from the ilwell E. Mohi festor Relations, Weyerh May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. [>any, Tacoma, WA 98471* Salvage of the timber blown down by the moun IA copy will be provided at no char Corporate Mailing Address tain's explosion is two-thirds complete on the Weyerhaeuser Company Tacoma, WA 98477 Weyerhaeuser lands involved, and by the end Director of Investor Relations of 1982 more than 15,000 acres will have Lowell E, Moholt Annual Meeting been reforested by planting crews ivho follow the Aptil 15, 1982 loggers. The company's large Longview, Weyerhaeuser Headquarters Building Washington, manufacturing complex has been Federal Way, Washington Pfoxy material will be mailed almost entirely supplied by wood salvaged on or about March 3, 1982 to from the blast zone, since September, 1980. each holder of record of voting shares. Dividends and Change of Address Communications concerning dividends and change of address shoufd be directed to the Cotp- Contents: orate Secretary, Weyerhaeuser Company, Tacoma, WA 98477. Transfer Agent Presidents Message 2 Communications concerning transfer requirements and lost stock certificates should be Timberlands and Raw Materials 6 addressed to the Transfet Agent. The First Jcfsey National Bank ^! One Exchange Place Wood Products 12 Jersey City, NJ 07 303 Dividend Investment Plan Fiber Products 16 A dividend investment plan is available to holders ul common shares. For brochure and enroll Weyerhaeuser Real Estate Company 20 ment forms write to the Corp orate Secretary, Weyerhaeuser Diversified Businesses 23 Company, Tacoma, WA 98477. -

Below Is Just a Sampling King County Companies Who Offer Matching Gifts

King County Employer Match From July 2014 issue of The Dirt Below is just a sampling King County companies who offer matching gifts. There are many companies likely not on the list so if you don’t see your company, or aren’t sure how to request your matching gift, simply contact your Human Resources department. Remember, the Foundation is a tax exempt, non-profit organization. Our IRS tax ID number is 91-1276404. AAA FM Global Foundation Parametrix ACCO Engineered Systems Food Services of America PCL Adobe Freddie Mac Foundation PEMCO Aetna Gap Foundation Pfizer Agilent Technologies General Dynamics Physicians Insurance Aleutian Spray Fisheries GeoEngineers Physio-Control Allied Insurance Glosten Assocs Piper-Jaffrey Allstate GM Nameplate Pitney Bowes Allysis Graham & Dunn Plum Creek Timber Company American Express Grange Insurance Group Polyclinic Amgen Foundation Green Diamond Resource Principal Financial Group Ameriprise Financial Green Tree Servicing Prudential Amgen Google Puget Sound Energy Anderson Corporation Hanover Insurance Quaker Hill Foundation Apex Foundation Hershey Food Corp Quorum Review Attachmate Co. Hewlett-Packard Quellos Avery Dennison Hoffman Construction Co of WA RealNetworks Bank of America Holland America Regence Blue Shield Bank of NY Mellon Honeywell REI Banner Bank Hospira Russell Investments Bassetti Architects ING Sabre Battelle Seattle Research Center Hyperion Matching Gifts Safeco Bearing Point JP Morgan Chase Saint-Gobain Matching Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Kellogg Company SaltChuk Resources Boeing