1 Accumulative Extremism: the Post-War Tradition of Anglo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a Hoax to Hate Introduction

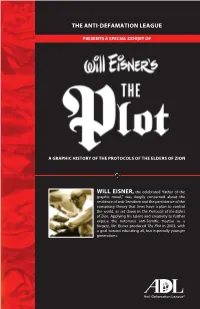

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE PRESENTS A SPECIAL EXHIBIT OF A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE PROTOCOLS OF THE ELDERS OF ZION WILL EISNER, the celebrated “father of the graphic novel,” was deeply concerned about the resilience of anti-Semitism and the persistence of the conspiracy theory that Jews have a plan to control the world, as set down in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Applying his talent and creativity to further expose the notorious anti-Semitic treatise as a forgery, Mr. Eisner produced The Plot in 2003, with a goal toward educating all, but especially younger generations. A SPECIAL EXHIBIT PRESENTED BY THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE ADL is proud to present a special traveling exhibit telling the story of the infamous forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, that has been used to justify anti-Semitism up to and including today. In 2005, Will Eisner’s graphic novel, The Plot: The Secret Story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published, exposing the history of The Protocols and raising public awareness of anti-Semitism. Mr. Eisner, who died in 2005, did not live to see this highly effective exhibit, but his commitment and spirit shine through every panel of his work on display. This project made possible through the support of the Will Eisner Estate and W.W. Norton & Company Inc. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Hoax to Hate Introduction It is a classic in the literature of hate. Believed by many to be the secret minutes of a Jewish council called together in the last years of the 19th century, it has been used by anti-Semites as proof that Jews are plotting to take over the world. -

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

STATEMENT by MR. ANDREY KELIN, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE of the RUSSIAN FEDERATION, at the 1045Th MEETING of the OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL

PC.DEL/393/15/Rev.1 25 March 2015 ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation STATEMENT BY MR. ANDREY KELIN, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, AT THE 1045th MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 19 March 2015 On the growth of racism, radicalism and neo-Nazism in the OSCE area Mr. Chairperson, The growth in manifestations of racism, violent extremism, aggressive nationalism and neo-Nazism remain, as ever, one of the most serious threats in the OSCE area. Unfortunately, the work in the OSCE to combat the spread of radical and neo-Nazi views within society is not being done systematically. Despite commitments in this area, there is no single OSCE action plan as there is for combating trafficking in human beings, improving the situation of Roma and Sinti or promoting gender equality. Every OSCE country has its problems connected with the growth of radicalism and nationalistic extremism. Russia is not immune to these abhorrent phenomena either. The approaches to resolving these problems in the OSCE participating States vary though. In our country, there is a package of comprehensive measures in place, ranging from criminal to practical, to nip these threats in the bud. Neo-Nazis and anyone else who incites racial hatred are either in prison or will end up there sooner or later. However, in many countries, including those that are proud to count themselves among the established democracies, people close their eyes to such phenomena or justify these activities with reference to freedom of speech, assembly and association. We are surprised at the position taken by the European Union, which attempts to find justification for neo-Nazi demonstrations and gatherings sometimes through particular historical circumstances and grievances and sometimes under the banner of democracy. -

Internal Brakes the British Extreme Right (Pdf

FEBRUARY 2019 The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation The British extreme right in the 1990s ANNEX B Joel Busher, Coventry University Donald Holbrook, University College London Graham Macklin, Oslo University This report is the second empirical case study, produced out of The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation: A Descriptive Typology programme, funded by CREST. You can read the other two case studies; The Trans-national and British Islamist Extremist Groups and The Animal Liberation Movement, plus the full report at: https://crestresearch.ac.uk/news/internal- brakes-violent-escalation-a-descriptive-typology/ To find out more information about this programme, and to see other outputs from the team, visit the CREST website at: www.crestresearch.ac.uk/projects/internal-brakes-violent-escalation/ About CREST The Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) is a national hub for understanding, countering and mitigating security threats. It is an independent centre, commissioned by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and funded in part by the UK security and intelligence agencies (ESRC Award: ES/N009614/1). www.crestresearch.ac.uk ©2019 CREST Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC-SA licence. www.crestresearch.ac.uk/copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................5 2. INTERNAL BRAKES ON VIOLENCE WITHIN THE BRITISH EXTREME RIGHT .................10 2.1 BRAKE 1: STRATEGIC LOGIC .......................................................................................................................................10 -

The New Faces of Fascism: Populism and the Far Right'

H-Nationalism Cârstocea on Traverso, 'The New Faces of Fascism: Populism and the Far Right' Review published on Tuesday, October 8, 2019 Enzo Traverso. The New Faces of Fascism: Populism and the Far Right. London: Verso, 2019. viii + 200 pp. $24.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-78873-046-4. Reviewed by Raul Cârstocea (University of Leicester) Published on H-Nationalism (October, 2019) Commissioned by Cristian Cercel (Ruhr University Bochum) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54462 Historicizing the Present: A Conceptual Reading of Postfascism Previously relegated to the dustbin of history, a specialist subject of seemingly antiquarian interest and otherwise popular only as a term of abuse meant to delegitimize one’s opponents, the last decade has seen “fascism” come back in fashion, in the tow of the other two terms making up the subtitle of Enzo Traverso’s book: populism and the Far Right. The increasing importance of the latter on the political spectrum, part and parcel of a resurgence of authoritarianism that is presently experienced globally, from the “Old” to the “New” Europe and from China, Russia, and Turkey to the United States and Brazil, has conjured up the specter of “fascism,” even for (the majority of) authors who find the association misleading. As such, despite the deluge of publications trading in the subject with more or less insight, a book that explicitly aims to link the two phenomena and analyze its contemporary iterations as “new faces of fascism” could not be more timely. From the outset however, we are introduced to another term, “postfascism,” according to the familiar and (still?) fashionable tendency to assign a “post” to everything, from “human” to “truth.” The “concept emphasizes its chronological distinctiveness and locates it in a historical sequence implying both continuity and transformation,” underlining “the reality of change” (p. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

Dossier on Glenn Greenwald

THE GLENN GREENWALD / MATT HALE LOVE AFFAIR GLENN GREENWALD’S LAW LICENSE WAS SUSPENDED FOR RECEIVING CODED MESSAGES FROM PRISON FROM HIS CLIENT AND PARAMOUR NAZI MATT HALE WHICH GLENN PASSED ON TO MEMBERS OF HALE’S CREW OF MISCREANTS UNTIL HE WAS QUESTIONED BY THE FBI JEWISH DEFENSE ORGANIZATION DOSSIER ON GLENN GREENWALD The writer who broke the NSA SNOWDEN PRISM story, Glenn Greenwald, is a traitor to the United States. Additionally, evidence suggests he was sexually attracted to the Nazi Matt Hale, which makes him one perverted Jew. His involvement with Hale went well beyond the normal attorney / client relationship. Glenn became an honorary member of Hale’s Church of the Creator and one of his crew. He represented the Church in every legal matter for five years for free, flying to Peoria to hook up with his client. He did illegal undercover work for Hale. Why risk imprisonment and loss of your law license if you do not believe in Nazi doctrine? The answer is Greenwald was in a relationship with Hale. We know Glenda is gay but what about Hale? For one thing Hale could never consummate a heterosexual relationship. Hale was married to a 16 year old for three months. Her name, according to the Nazis, was THE GLENN GREENWALD / MATT HALE LOVE AFFAIR ―Terra Heron.‖ Then he married Peggy Anderson in 1997 but he was divorced shortly thereafter. Hale was never attracted to women and was unable to perform in bed. He moved back in with his father. He spent 30 years with his father Russell Hale who croaked in 2012. -

TURNING the PAGE on HATE Huge Quantities Of

HOPE NOT HATE BRIEFING: TURNING THE PAGE ON HATE MARCH 2018 WWW.HOPENOTHATE.ORG.UK TURNING THE PAGE ON HATE By the Right Response Team SUMMARY OUR POSITION ■ An investigation by HOPE not hate’s Right ■ While we abhor these books HOPE not hate is Response team has found huge quantities of not saying that people do not have the right extreme hate content being sold by the major to write and publish books we disagree with. book sellers Waterstones, Foyles, WHSmith We are arguing that major mainstream book and Amazon. sellers such as Waterstones, Foyles, Amazon ■ All 4 companies sell the Turner Diaries or WHSmith should not profit from extreme which has inspired numerous violent racists hate content such as this. and terrorists, including the Oklahoma City ■ Our further major concern is that bomber Timothy McVeigh, who killed 168 these extreme books and authors gain people using a truck bomb similar to one respectability by virtue of their publications described in detail in the book. Purchasing being available on the websites of trusted the Turner Diaries at Foyles gets you 48 and mainstream sellers. Foyalty points as part of their loyalty scheme. ■ We accept that Amazon took the step of ■ Waterstones, Foyles and Amazon companies removing three Holocaust denial titles in sell the antisemitic forgery The Protocols of 2017, a move we of course welcome, but the Learned Elders of Zion which has been much more needs to be done. Worryingly described as a “warrant for genocide”. some of the books they removed are ■ Large amounts of extreme Holocaust denial still available via other sellers such as literature is available via these sellers. -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

Identifying Extreme Racist Beliefs

identifying extreme racist beliefs What to look out for and what to do if you see any extreme right wing beliefs promoted in your neighbourhood. At Irwell Valley Homes, we believe that everyone has the If you see any of these in any of the neighbourhoods right to live of life free from racism and we serve, please contact us straight away on 0300 discrimination. However, whilst we work to promote 561 1111 or [email protected]. We take equality, racism still exists and we want to take action to this extremely seriously and will work with the Greater stop this. Manchester Police to deal with anyone responsible. This guide helps you to identify some of the numbers, signs and symbols used to promote extreme right wing beliefs including racism, extreme nationalism, fascism and neo nazism. 18: The first letter of the alphabet is A; the eighth letter of the alphabet is H. so, 1 plus 8, or 18, equals AH, an abbreviation for Adolf Hitler. Neo-Nazis use 18 in tat- toos and symbols. The number is also used by Combat 18, a violent British neo-Na- zi group that chose its name in honour of Adolf Hitler. 14: This numeral represents the phrase “14 words,” the number of words in an ex- pression that has become the slogan for the white supremacist movement. 28: The number stands for the name “Blood & Honour” because B is the 2nd letter of the alphabet and H is the 8th letter. Blood & Honour is an international neo-Nazi/ racist skinhead group started by British white supremacist and singer Ian Stuart.