Swithland Slate Headstones David Lea Pp51-110

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submissionversion

SILEBY NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2018 – 2036 Submission version Page left deliberately blank 2 Contents Chapter heading Page Foreword from the Chair 4 1. Introduction 6 2. How the Neighbourhood Plan fits into the planning system 8 3. The Plan, its vision, objectives and what we want it to achieve 10 4. How the Plan was prepared 12 5. Our Parish 14 6. Meeting the requirement for sustainable development 19 7. Neighbourhood Plan Policies 20 General 20 Housing 26 The Natural and Historic Environment 35 Community Facilities 58 Transport 65 Employment 74 8. Monitoring and Review 78 Appendix 1 – Basic Condition Statement (with submission version) Appendix 2 – Consultation Statement (with submission version) Appendix 3 – Census Data, Housing Needs Report and SSA report Appendix 4 – Environmental Inventory Appendix 5 – Local Green Space Assessments Appendix 6 – Buildings and Structures of local significance Appendix 7 – Study of traffic flows in Sileby (transport appendices) 3 Foreword The process of creating the Sileby Neighbourhood Plan has been driven by Parish Councillors and members of the community and is part of the Government’s approach to planning contained in the Localism Act of 2011. Local people now have a greater say through the planning process about what happens in the area in which they live by preparing a Neighbourhood Plan that sets out policies that meet the need of the community whilst having regard for local, national and EU policies. The aim of this Neighbourhood Plan is to build and learn from previous community engagement and village plans and put forward clear wishes of the community regarding future development. -

Roundabout, 2012, 03

Editorial policy Roundabout aims to promote local events, groups and businesses and to keep everyone informed of anything that affects our community. We avoid lending support (in the form of articles) to any social, political or religious causes, and we reserve the right to amend or omit any items submitted. The final decision rests with the editors. While Roundabout is supported by Woodhouse Parish Council, we rely on advertisements to pay production costs, and we accept advertisements for local businesses as well as those that publicise charitable and fund-raising events. Brief notification of events in the ‘What’s on’ schedule is free. Copyright in any articles published is negotiable but normally rests with Roundabout. We apologise for any errors that might occur during production and will try to make amends in the following issue. Roundabout needs your input. For guidelines on submission, please see inside the back cover. Management and production Roundabout is managed on behalf of the community and published by the Editorial and Production Team comprising Richard Bowers, Evelyn Brown, Peter Crankshaw, Amanda Garland, Andrew Garland, Tony Lenney, Rosemary May, Neil Robinson, Grahame Sibson and Andy Thomson. Content editor for this issue: Evelyn Brown Cover: Neil Robinson Advertising managers: Amanda and Andrew Garland Desk-top publishing (page layout) for this issue: Richard Bowers Printing: Loughborough University Printing Services Roundabout is available to read or download from the parish council website at www.woodhouseparishcouncil.org.uk/roundabout.html Distribution: Roundabout is delivered by volunteers to every address within the parish boundary – just under 1000 households and businesses, including all the surrounding farms. -

Barrow Upon Soar Local Walks

Local Walks AROUND BARROW UPON SOAR www.choosehowyoumove.co.uk These walks include the loop of the River Soar as it curves from Barrow to Quorn, the canal, surrounding wolds countryside and Charnwood Hills. The parish comprises the village, the River Soar, Grand Union Canal, working railway, Barrow Gravel Pits, one of oldest surviving valley pits in the county and a derelict willow osier bed (grid ref 580158), Barrow Hill, disused lime pits and hedgerows rich in wildlife and flora route linking Leicester with the Trent and Mersey Canal. START: Public car park at Old Station Close at south end of High NOTES: Do not attempt walks 3 and 4 when the river is in flood, or for Street. Nearest postcode LE12 8QL, Ordnance Survey Grid Reference several days afterwards. For details visit www.environment-agency.gov.uk. 457452 317352 - Explorer Map 246. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: With thanks to the Ramblers, Britain’s PARKING: Public Car Park, Old Station Close. walking charity, who have helped develop this local walk. For more For more information GETTING THERE: information and ideas for walks visit www.ramblers.org.uk and to report Plan your journey on foot, by bike, public transport or car by visiting problems contact: www.choosehowyoumove.co.uk or calling Traveline on 0871 200 22 33 Tel 0116 305 0001 (charges apply) for the latest public transport information. Email footpaths@ leics.gov.uk Local Walks AROUND BARROW UPON SOAR www.choosehowyoumove.co.uk Walk 1: A walk to Barrow Deep Lock and From the car park turn left over E. Turn right over the railway railway bridge into High Street, bridge and right into Breachfield Easy Millennium Park with views of the river and then left along Cotes Road to Road. -

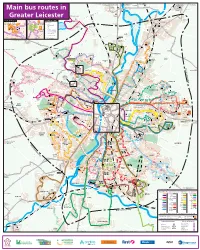

Main Bus Services Around Leicester

126 to Coalville via Loughborough 27 to Skylink to Loughborough, 2 to Loughborough 5.5A.X5 to X5 to 5 (occasional) 127 to Shepshed Loughborough East Midlands Airport Cossington Melton Mowbray Melton Mowbray and Derby 5A 5 SYSTON ROAD 27 X5 STON ROAD 5 Rothley 27 SY East 2 2 27 Goscote X5 (occasional) E 5 Main bus routes in TE N S GA LA AS OD 126 -P WO DS BY 5A HALLFIEL 2 127 N STO X5 SY WESTFIELD LANE 2 Y Rothley A W 126.127 5 154 to Loughborough E S AD Skylink S 27 O O R F N Greater Leicester some TIO journeys STA 5 154 Queniborough Beaumont Centre D Glenfield Hospital ATE RO OA BRA BRADG AD R DGATE ROAD N Stop Services SYSTON TO Routes 14A, 40 and UHL EL 5 Leicester Leys D M A AY H O 2.126.127 W IG 27 5A D H stop outside the Hospital A 14A R 154 E L A B 100 Leisure Centre E LE S X5 I O N C Skylink G TR E R E O S E A 40 to Glenfield I T T Cropston T E A R S ST Y-PAS H B G UHL Y Reservoir G N B Cropston R ER A Syston O Thurcaston U T S W R A E D O W D A F R Y U R O O E E 100 R Glenfield A T C B 25 S S B E T IC WA S H N W LE LI P O H R Y G OA F D B U 100 K Hospital AD D E Beaumont 154 O R C 74, 154 to Leicester O A H R R D L 100 B F E T OR I N RD. -

Rural Grass Cutting III Programme 2021 PDF, 42 Kbopens New Window

ZONE 1 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 1 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 1 30th August - 5th September Primethorpe Broughton Astley Willoughby Waterleys Peatling Magna Ashby Magna Ashby Parva Shearsby Frolesworth Claybrooke Magna Claybrooke Parva Leire Dunton Bassett Ullesthorpe Bitteswell Lutterworth Cotesbach Shawell Catthorpe Swinford South Kilworth Walcote North Kilworth Husbands Bosworth Gilmorton Peatling Parva Bruntingthorpe Upper Bruntingthorpe Kimcote Walton Misterton Arnesby ZONE 2 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 2 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 2 23rd August - 30th August Kibworth Harcourt Kibworth Beauchamp Fleckney Saddington Mowsley Laughton Gumley Foxton Lubenham Theddingworth Newton Harcourt Smeeton Westerby Tur Langton Church Langton East Langton West Langton Thorpe Langton Great Bowden Welham Slawston Cranoe Medbourne Great Easton Drayton Bringhurst Neville Holt Stonton Wyville Great Glen (south) Blaston Horninghold Wistow Kilby ZONE 3 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. The roads surrounding the close by villages and towns fall within Zone 3 DATE RANGE PARISHES WITHIN ZONE 3 16th August - 22nd August Stoughton Houghton on the Hill Billesdon Skeffington Kings Norton Gaulby Tugby East Norton Little Stretton Great Stretton Great Glen (north) Illston the Hill Rolleston Allexton Noseley Burton Overy Carlton Curlieu Shangton Hallaton Stockerston Blaston Goadby Glooston ZONE 4 The rural grass cutting takes 6 weeks to complete and is split into 10 zones. -

June 2013 the Parish of Birstall and Wanlip

JUNE 2013 THE PARISH OF BIRSTALL AND WANLIP 3 PARISH DIARY JUNE—AUGUST 2013 JUNE 2nd 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 16th 6pm Christian Unity Sunday Evensong at Wanlip with Speaker from “GATES” 22nd 9am Coach trip to Gloucester 29/30th Birstall Gala 30th Service on the Park JULY 7th 10 am ‘All Together’ Service 8th—12th Parish Holiday to Cober Hill 27th 10 am Parish Away Day at Nanpantan AUGUST 1st 10 am ‘All Together’ service led by Home Groups 4th 7.30 pm Home Groups Get Together 11th 10 am Mothers’ Union Service 26th 2pm Parish Garden Fete on the Church Lawn Details of our regular services can be found on page 6 Please see church information sheets and/or website www.birstall.org for further information 4 Welcome Welcome to the summer edition of ‘Link’. I hope you find it informative, useful and interesting. It is the first put together ‘under new management’ since our friend - and editor of many years - Maureen Holland died in April. It is due to Maureen’s efforts that ‘Link’ exists today; a link with the Church which we hope to continue to provide you with for a long time to come. Our website editor, Gill Pope, has taken over the production editorial role, Noreen Talbot continues as commissioning editor. Gill and Noreen welcome your contributions as well as your feedback in order to help them make it the magazine that you look forward to receiving and reading each quarter. Thank you for your continued interest in, and support of, the Church. -

Division Arrangements for Thurmaston Ridgemere

East Goscote Rearsby Ratcliffe on the Wreake Cossington Rothley & Mountsorrel Rothley Syston Fosse Queniborough Gaddesby Syston Melton Wolds Syston Ridgeway Wanlip Twyford & Thorpe South Croxton Barkby Leicestershire Birstall Birstall Thurmaston Thurmaston Ridgemere Lowesby Beeby Barkby Thorpe Hungarton Launde Cold Newton Keyham Scraptoft Billesdon County Division Parish 0 0.375 0.75 1.5 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Thurmaston Ridgemere © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Lockington-Hemington Castle Donington & Kegworth Castle Donington Kegworth Isley cum Langley Long Whatton & Diseworth Breedon on the Hill Hoton Hathern Loughborough North Cotes Sileby & The Wolds Staunton Harold Prestwold Valley Loughborough East Burton on the Wolds Belton Worthington Walton on the Wolds Osgathorpe Shepshed Loughborough North West Shepshed Loughborough South Barrow upon Soar Loughborough South West Ashby de la Zouch Coleorton Leicestershire Quorn & Barrow Ashby-de-la-Zouch Ashby Woulds Swannington Quorndon Whitwick Whitwick Charley Sileby Mountsorrel Woodhouse Packington Coalville North Forest & Measham Ravenstone with Snibstone Oakthorpe & Donisthorpe Bardon Rothley & Mountsorrel Normanton Le Heath Coalville South Swithland Rothley Ulverscroft Bradgate Hugglescote & Donington le Heath Measham Ellistown & Battleflat Thurcaston & Cropston Ibstock & Appleby Markfield Swepstone Newtown Linford Syston Ridgeway Stretton en le Field Chilcote Heather Stanton-under-Bardon -

Footway Slurry Seal Programme 2007/08

FOOTWAY SLURRY SEAL PROGRAMME 2007/08 Programme under construction Site No Village 1 Anstey 2 Anstey 3 Anstey 4 Anstey 5 Anstey 6 Anstey 7 Birstall 8 Birstall 9 Birstall 10 Birstall 11 Birstall 12 Birstall 13 Loughborough 14 Loughborough 15 Loughborough 16 Loughborough 17 Loughborough 18 Loughborough 19 Loughborough 20 Loughborough 21 Loughborough 22 Loughborough 23 Loughborough 24 Loughborough 25 Loughborough 26 Loughborough 27 Loughborough 28 Loughborough 29 Loughborough 30 Loughborough 31 Loughborough 32 Loughborough 33 Loughborough 34 Loughborough 35 Loughborough 36 Loughborough 37 Mountsorrel 38 Mountsorrel 39 Mountsorrel 40 Mountsorrel 41 Mountsorrel 42 Mountsorrel 43 Mountsorrel 44 Mountsorrel 45 Mountsorrel 46 Mountsorrel 47 Mountsorrel 48 Newtown Linford 49 Newtown Linford Page 1 50 Quorn 51 Sileby 52 Sileby 53 Syston 54 Syston 55 Syston 56 Syston 57 Thurmaston 58 Thurmaston 59 Thurmaston Page 2 APPENDIX D FOOTWAY SLURRY SEAL PROGRAMME 2007/08 CHARNWOOD DISTRICT Location Link Road (Bradgate Road to Dalby Road) Charles Drive Andrew Road King Williams Way Edward Street (Part) Nertherfield Road Briargate Drive Saltersgate Drive Harrowgate Drive Ludgate Close Knollgate Close Queensgate Drive Clowbridge Drive Wilstone Close Chelker Way Blithefield Avenue Rowbank Way Crosswood Close Afton Close Sywell Avenue Pevensey Road Durham Road Rockingham Road Oakham Close North Road Byron Street Extension Braddon Road Lyall Close Leslie Close Canning Way Gardner Close Knightthorpe Road Thorpe Hill Nottingham Road (Conneries to Ratcliffe Road) -

Private Residents. { and Rutland

LEICESTERSHIRE 1 716 woo PRIVATE RESIDENTS. { AND RUTLAND. Wood William, Harwarden villas, Lei- Wootton W: H. 1.P. 2 Victoria street, Wright T. W. The Elms, Elms park, cester road, Hinckley .Loughborough Loughborough Wood William Chandler, Glenholme, Wootton WaIt. 9 Herrick rd.Loughboro' WrightW J.p.OneAsh,Quom,Loughboro' Glenfield, Leicester Wordsworth Wm. Erin, Quom, Lghboro' Wright Waiter, The Warren, Woodhouse Wood William Joseph Henry, Rutland Wormleighton Harry, Caer-Lerion, Eaves, Loughborough hous£>, Syston, Leicester Knighton Grange road, Leicester Wyatt Wilham, Whetstone, Leicester Woodcock Christopher Cleever, The Wormleighton ,Mrs. Bitteswell road, Wykes Major Lewis Vincent, Hall Leys, Homestead, Thrussington, Leicester Lutterworth Stoughton road, Oadby, Leicester Woodcock F. Northcroft, Blaby, Leicestr Wormleighton William John, Woodville, Wykes Mrs. Leicester road, Ashby- Woodcock Frank C. Gainsborough villa, Dunton Bassett, Lutterworth de-Ia-Zouch Narborough, Leicester . WorrallEdwd.d.p.TheHall,Wing,Oakhm Wykes Percy, Woodlands, Swithland WoodcockMiss,4WyclifIe ter.Lutterwrth Worrall Philip, The Hall, Wing, Oakham lane, Rothley, Leicester Woodcock Reginald Boyd, The Haven, Worswick Mrs. Burbage hall, Burbage, Wykes W. H. North st.Hugglescote,Lcstr Birstall hill, Birstall, Leicester Hinckley Wynter Col. Walter Andrew, Long Close, Woodcock Thomas, Wanlip road, Sys- WorthingtonMisses,Thurlaston,Hinckley Woodhouse Eaves, Loughborough ton, Leicester Wragg Horace, Highfield hOllse, Ashby Yarborough Victoria Alexandrina, Woodford Mrs. Barkby, Leicester Woulds, Ashby-de-Ia-Zouch Countess of, Edmondthorpe hall, Woodhouse Vivian Mackay, The Old Wragg Miss, 68 Leicesterrd.Loughboro' Oakham Hall, Queniborough, Leicester Wright· Rev. Thomas B.A. Vicarage, Yate Col. Charles Edward C.S.I., C.M.G., Woodroffe Mrs. 12 Burton st.Loughboro' Frisby-on-the-Wreak, Leicester M.P., D.L. -

Wymeswold Parish Walk

5½km (3¼miles), allow Walk 3: 2 hours, across open countryside with interesting views Wymeswold This leaflet is one of a series produced to promote Follow directions for Walk 2 until point 6. For this circular walking throughout the county. You can obtain route cross the stile that is mentioned and continue others in the series by visiting your local library or Wymeswold keeping the hedge on the left. Soon turn right and Tourist Information Centre. You can also order them walk parallel to the hedge on the right. Turn right by phone or from our website. circular again to cross the field boundary and continue through Bottesford walks the next field with the hedge now on the left. Muston 3 Redmile 1 Cross two stiles then turn diagonally right aiming for 4¾kms/3 miles the far right hand corner of the next field. The tower of 2 4½kms/2¾ miles Wymeswold church soon comes into view. There are 3 5½kms/3¼ miles Wymeswold Scalford Hathern also wonderful views of the hills of Charnwood Forest Burton on the Wolds Thorpe Acre & Prestwold Asfordby in the distance. Barrow upon Soar Frisby li At the field corner turn left and take the path with Normanton le Heath Barkby the hedge on your right. Halfway across the next field, Ibstock Twyford Go through a hand gate and continue along the brook. by the electricity wires, turn right and walk down the Appleby Swepstone Anstey Hungarton Magna Groby Tilton & Lowesby Then walk diagonally up to another hand gate which field in line with the church tower. -

The Wolds Historian No. 3 2006

Contents Chairman’sreport 2006 Welcome to this the third issue of The Wolds Historian. One of the articles reveals that much Chairman's report 2005 1 heritage is being lost as a result of village growth. I The airfield in our midst 2 therefore make a plea for all ‘at risk’ features to be recorded and photographed so that information Polish camp revisited 19 will not be lost to future generations of local historians. Articles, short or long, based on such Wymeswold'swells 20 features throughout the Woldsare most welcome Village life in nineteenth century Hoton 21 for publication in future issues of The Wolds Historian. Will of JoanGroves of Wymeswold 27 The WoldsHistorical Organisation meets Burton'sheritage lost in 2006 28 regularly on the third Tuesday in the month (except July and August) with a variety of speakers and a walk in June. This year WHO member Colin Lines gave an excellent insight into the steam fairground rides of FrederickSavage; Jack Smirfitt enlightened members about framework knitting, followed by a visit to RuddingtonFramework Knitting Museum; ThomasLeafe’stalk on nineteenth century pit boys made us aware of how easy life is today; ErnestMiller explained the history of ancient board games, with members honing their practical playing skills with Nine Front cover: The front cover of the souvenir Mens’ Morris; while HelenBoyntoninstructed us programme for the open day at RAF Wymeswold in the geology of CharnwoodForest and the on Saturday 15thSeptember 1956 (original in unique fossils in the old rocks. colour, kindly loaned by DavidPutt. Anyone with an interest in local and wider history is most welcome to attend WHO meetings. -

NOTICE of POLL Leicestershire County County Election of a County Councillor for Sileby & the Wolds

NOTICE OF POLL Leicestershire County County Election of a County Councillor for Sileby & The Wolds Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Sileby & The Wolds will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors ADDINALL (Address in the The For Britain Ian D W Margetts (+) Joanne C Y Margetts George Frederick Charnwood area) Movement (++) MORRIS 1 Christie Drive, Reform UK Donald C Randle (+) Andrea J Jenkins (++) Pete Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 5YR RICHARDS 122 Seagrave Road, Green Party Katie M Richards (+) Benjamin P Mastericks Billy Sileby, Leicestershire, (++) LE12 7TR SEGGIE (Address in the Labour Party Valerie S Marriott (+) Andrew C Marriott (++) Andrew John Charnwood area) Robertson SHARPE (Address in the Liberal Democrats Martin J Weedon (+) Wendy A Sharpe (++) Ian Robert Charnwood area) SHEPHERD 73 Leicester Road, The Conservative Party Paul G Murphy (+) Robert Shields (++) Richard James Quorn, Leicestershire, Candidate LE12 8BA 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of