Decolonizers of the Imaginary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BARRY N. MALZBERG Introduction by D

REVELATIONS A Paranoid Novel of Suspense BARRY N. MALZBERG Introduction by D. Harlan Wilson AP ANTI-OEDIPUS PRESS Revelations Copyright © 1972 by Barry N. Malzberg ISBN: 978-0-99-915354-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934879 First published in the United States by Warner Paperback First Anti-Oedipal Paperback Edition: March 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author and publisher. Published in the United States by Anti-Oedipus Press, an imprint of Raw Dog Screaming Press. www.rawdogscreaming.com Introduction © 2020 by D. Harlan Wilson Afterword © 1976 by Barry N. Malzberg Afterword to an Afterword © 2019 by Barry N. Malzberg Cover Design by Matthew Revert www.matthewrevert.com Interior Layout by D. Harlan Wilson www.dharlanwilson.com Anti-Oedipus Press Grand Rapids, MI www.anti-oedipuspress.com SF SCHIZ FLOW PRAISE FOR THE WORK OF BARRY N. MALZBERG “There are possibly a dozen genius writers in the genre of the imaginative, and Barry Malzberg is at least eight of them. Malzberg makes what the rest of us do look like felonies!” —Harlan Ellison “Malzberg makes persuasively clear that the best of science fiction should be valued as literature and nothing else.” —The Washington Post “One of the finest practitioners of science fiction.” —Harry Harrison “Barry N. Malzberg’s writing is unparalleled in its intensi- ty and in its apocalyptic sensibility. His detractors consider him bleakly monotonous and despairing, -

Panels Seeking Participants

Panels Seeking Participants • All paper proposals must be submitted via the Submittable (if you do not have an account, you will need to create one before submitting) website by December 15, 2018 at 11:59pm EST. Please DO NOT submit a paper directly to the panel organizer; however, prospective panelists are welcome to correspond with the organizer(s) about the panel and their abstract. • Only one paper proposal submission is allowed per person; participants can present only once during the conference (pre-conference workshops and chairing/organizing a panel are not counted as presenting). • All panel descriptions and direct links to their submission forms are listed below, and posted in Submittable. Links to each of the panels seeking panelists are also listed on the Panel Call for Papers page at https://www.asle.org/conference/biennial-conference/panel-calls-for-papers/ • There are separate forms in Submittable for each panel seeking participants, listed in alphabetical order, as well as an open individual paper submission form. • In cases in which the online submission requirement poses a significant difficulty, please contact us at [email protected]. • Proposals for a Traditional Panel (4 presenters) should be papers of approximately 15 minutes-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. Please include your name and contact information in this file. • Proposals for a Roundtable (5-6 presenters) should be papers of approximately 10 minute-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. -

Solarpunk: L'utopia Che Vuole Esistere a Cura Di Giulia Abbate E Romina Braggion

Solarpunk: l'utopia che vuole esistere a cura di Giulia Abbate e Romina Braggion Zest Letteratura sostenibile | © Tutti i diritti riservati I Per ZEST Letteratura sostenibile | 2020 Progetto Prose Selvatiche – Osservatorio sull'Eco-fiction www.zestletteraturasostenibile.com Tutti i diritti riservati in copertina immagine di Rita Fei Zest Letteratura sostenibile | © Tutti i diritti riservati II Prima la domanda: perché? Nato negli anni '10 di questo secolo, emanazione diretta della fantascienza quanto dell'eco-fiction classica, il solarpunk ha alcune caratteristiche che hanno richiamato la nostra attenzione e che troviamo utile sistematizzare e far conoscere. Questo perché il solarpunk si fa interprete di sentimenti e istanze attualissime e utili a un progresso collettivo, organico, equo, ecologico, inclusivo; si esplicita in un comparto visuale che va oltre la mera suggestione estetica; fin dai suoi inizi esprime una visione politica complessa e aperta a vari contributi, ma chiara. È un genere, insomma, che potrebbe essere un movimento: potrebbe aiutarci non solo a immaginare un futuro migliore, ma anche a costruire strategie operative per avvicinarci a tali visioni condivise. Radici: le immagini Risalire alle le radici del solarpunk è stata una scoperta: ci ha portate su strade affatto scontate, in un lavoro di ricostruzione cross-mediale. Queste radici non sono letterarie, ma legate al mondo di Tumblr, una piattaforma di comunicazione di nicchia: mescola il microblogging con la diffusione social, dando la preminenza a contenuti visuali; è qui che il solarpunk ha mosso i suoi primi passi, identificandosi in una serie di immagini, che mostravano mondi futuri diversi da quelli a cui ci ha abituato la distopia postapocalittica e l'immaginario urbano cyberpunk. -

Asfacts Oct19.Pub

doon in 2008. His final story, “Save Yourself,” will be published by BBC Books later this year. SF writers in- Winners for the Hugo Awards and for the John W. cluding Charlie Jane Anders, Paul Cornell, and Neil Campbell Award for Best New Writer were announced Gaiman have cited his books as an important influence. August 18 by Dublin 2019, the 77th Worldcon, in Dub- Dicks also wrote over 150 titles for children, including lin, Ireland. They include a couple of Bubonicon friends the Star Quest trilogy, The Baker Street Irregulars series, – Mary Robinette Kowal, Charles Vess, Gardner Dozois, and The Unexplained series, plus children’s non-fiction. and Becky Chambers. The list follows: Terrance William Dicks was born April 14, 1935, in BEST NOVEL: The Calculating Stars by Mary Robi- East Ham, London. He studied at Downing College, nette Kowal, BEST NOVELLA: Artificial Condition by Cambridge and joined the Royal Fusiliers after gradua- Martha Wells, BEST NOVELETTE: “If at First You Don’t tion. He worked as an advertising copywriter until his Succeed, Try, Try Again” by Zen Cho, BEST SHORT STO- mentor Malcolm Hulke brought him in to write for The RY: “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendi- Avengers in the ’60s, and he wrote for radio and TV be- um of Portal Fantasies” by Alix E. Harrow, BEST SERIES: fore joining the Doctor Who team in the late ’60s. He Wayfarers by Becky Chambers, BEST GRAPHIC STORY: also worked as a producer on various BBC programs. He Monstress, Vol 3: Haven by Marjorie Liu and illustrated is survived by wife Elsa Germaney (married 1963), three by Sana Takeda, sons, and two granddaughters. -

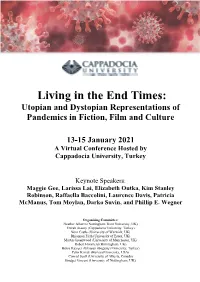

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

Resistant Female Cyborgs in Brazil

Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía Volume 7 Issue 1 Ibero-American Homage to Mary Article 5 Shelley Resistant Female Cyborgs in Brazil M. Elizabeth Ginway University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ginway, M. Elizabeth (2020) "Resistant Female Cyborgs in Brazil," Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2167-6577.7.1.5 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique/vol7/iss1/5 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Ginway: Resistant Female Cyborgs in Brazil In her oft-cited “A Cyborg Manifesto,” (1985) Donna Haraway conceptualizes the cyborg as a feminist possibility, emphasizing the need for a self-created, self-engendered female, free from the demands of capitalism and the Freudian neuroses caused by traditional family life (150). In How We Became Posthuman (1999), N. Katherine Hayles identifies three stages of cybernetic theory from the 1940s to the present, i.e., cybernetic feedback loops, reflexivity and pattern recognition,1 which she uses to analyze to science fiction’s portrayals of artificially enhanced humans, androids and artificial intelligence. In this article, I discuss examples of Brazilian artificial humans in works by Caio Fernando Abreu, Roberto de Sousa Causo and João Paulo Cuenca that follow the trajectory described by Hayles and raise the gender issues discussed by Haraway. -

O ANTI-FUTURISMO SOLARPUNK: Desenvolvimento De Uma Estética Figurativa E Narrativa ANEXOS

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES O ANTI-FUTURISMO SOLARPUNK: Desenvolvimento de uma Estética Figurativa e Narrativa ANEXOS João Ricardo Santos de Matos Fortuna Trabalho de Projeto Mestrado em Desenho Trabalho de Projeto orientado pelo Prof. Doutor António Pedro Ferreira Marques ANO 2021 2 3 Anexos Entrevista a Dustin Jacobus João - I found solarpunk 10 years ago, like rumors on the internet. It was little more than an idea badly defined and at that time the only work published was an anthology book of the same name in Brazil, only recently translated to English. The rest were works of eco-fiction that came as far back as the 60's but didn't identify themselves as solarpunk. So, I would like to know, how did you find solarpunk and what was your first experience with it? D. Jacobus - About a year ago, I started collaborating on a design guide made by Eric Hunting. Eric noticed there was a lot of confusion as to what Solarpunk means and for that reason, he decided to write, “Solarpunk: post-industrial design and aesthetics.” Just like you, I was familiar with Solarpunk and for me too it remained a bit vague. While sketching for Eric’s paper, I read different articles about Solarpunk. I noticed there was much more interest on the Solarpunk theme than before. At the same time I worked on my own art publication, called Universitas. I decided to link it to the Solarpunk theme. My own work has many similarities with Eric’s work and other descriptions/narratives about Solarpunk. -

June 2020 June 2020 June 2020 June 2020

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 field notes art books Normality is Death by Jacob Blumenfeld 6 Greta Rainbow on Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects 88 Where Is She? by Soledad Álvarez Velasco 7 Kate Silzer on Excerpts from the1971 Journal of Prison in the Virus Time by Keith “Malik” Washington 10 Rosemary Mayer 88 Higher Education and the Remaking of the Working Class Megan N. Liberty on Dayanita Singh’s by Gary Roth 11 Zakir Hussain Maquette 89 The pandemics of interpretation by John W. W. Zeiser 15 Jennie Waldow on The Outwardness of Art: Selected Writings of Adrian Stokes 90 Propaganda and Mutual Aid in the time of COVID-19 by Andreas Petrossiants 17 Class Power on Zero-Hours by Jarrod Shanahan 19 books Weston Cutter on Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League art and Luke Geddes’s Heart of Junk 91 John Domini on Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne ART IN CONVERSATION and Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s Seeing the Body: Poems 92 LYLE ASHTON HARRIS with McKenzie Wark 22 Yvonne C. Garrett on Camille A. Collins’s ART IN CONVERSATION The Exene Chronicles 93 LAUREN BON with Phong H. Bui 28 Yvonne C. Garrett on Kathy Valentine’s All I Ever Wanted 93 ART IN CONVERSATION JOHN ELDERFIELD with Terry Winters 36 IN CONVERSATION Jason Schneiderman with Tony Leuzzi 94 ART IN CONVERSATION MINJUNG KIM with Helen Lee 46 Joseph Peschel on Lily Tuck’s Heathcliff Redux: A Novella and Stories 96 june 2020 THE MUSEUM DIRECTORS PENNY ARCADE with Nick Bennett 52 IN CONVERSATION Ben Tanzer with Five Debut Authors 97 IN CONVERSATION Nick Flynn with Elizabeth Trundle 100 critics page IN CONVERSATION Clifford Thompson with David Winner 102 TOM MCGLYNN The Mirror Displaced: Artists Writing on Art 58 music David Rhodes: An Artist Writing 60 IN CONVERSATION Keith Rowe with Todd B. -

Cyberpunk 2077 Review

RPG REVIEW Issue #49-50, Dec-Mar 2020-2021 ISSN 2206-4907 (Online) Proceedings of "Cyberpunk 2020: Year of the Stainless Steel Rat" Convention Proceedings, Articles, and Scenarios Keynote by Walter Jon Williams What Was/Is Cyberpunk? ¼ Hackers and IT Security Issues ¼ Cyberculture ¼ Technology Trends and Solarpunk ¼ Anarchist Politics ¼ Gaming and Cyberpunk ¼ GURPS Biotech ¼ Cyberpunk 2020, Cyberspace, Scenarios ¼ GURPS Biotech ¼ and more! 1 RPG REVIEW ISSUE 49-50 Dec to Mar 2020-2021 Table of Contents ADMINISTRIVIA.........................................................................................................................................................2 EDITORIAL AND COOPERATIVE NEWS................................................................................................................2 WHAT WAS/IS CYBERPUNK?...................................................................................................................................7 HACKERS: THE IT SECURITY PANEL..................................................................................................................17 TECHNOLOGY : CYBERPUNK AND SOLARPUNK.............................................................................................26 POLITICS: ANARCHISM, LIBERTARIANISM, CYPHERPUNKS........................................................................35 CYBERCULTURE PANEL........................................................................................................................................44 CYBERPUNK GAMING............................................................................................................................................56 -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Steampunk – Retro-Futurismus als ästhetisches Mittel“ Verfasserin Lisa Theres Schranz angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. habil. Michael Gissenwehrer Danksagung Eine wissenschaftliche Arbeit dieser Größe ist kaum alleine zu bewältigen. Daher möchte ich an dieser Stelle meine tiefe Dankbarkeit ausdrücken. Vielen Dank meinen Freunden für das Verständnis, die Geduld und fürs Rücken stärken, jede und jeder Einzelne haben auf unterschiedliche Weise dazu beigetragen diese Arbeit zu vollenden. Ganz besonders Lukas Tröscher, Friedrich Schumann und Elisabeth Bürger mit ihrem strengen Blick und ihrer konstruktive Kritik. Ganz großer Dank gebührt auch meiner ganzen Familie. Besonders meiner Mutter, meinen Brüdern, meiner Tante und meiner Cousine für ihren Rückhalt und die bedingungslose Unterstützung auf moralischer sowie finanzieller Ebene, die mir erst das Studium und nun den Abschluss ermöglichten. ~ 2 ~ Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 2. Der Begriff Steampunk 3. Die Wiege des Steampunk: Die Literatur 3.1. Zwei Richtungen 3.2. Die scheinbare Verifikation 3.3. Kategorisierung der Steampunk-Literatur 3.3.1. Viktorianische Science Fiction 3.3.2. Retro-Science-Fiction 3.3.3. Steampunk - Ein neues Genre 3.3.4. Steampunk heute 4. Die Entwicklung der Steampunk-Ästhetik: Filme 4.1. Disney und Steampunk 4.2. Die Filme vor 1987 4.3. Die ersten Steampunk-Filme 4.4. Der Boom der 2000er 4.5. Terry Gilliam und Tim Burton 4.5.1. Gilliams Anachronismus 4.5.2. Burtons schräge Märchen 4.6. Musikvideos 4.6.1. Die erste Steampunk-Welle 4.6.2. -

Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture

University of Alberta The Steampunk Aesthetic: Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture by Mike Dieter Perschon A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature © Mike Dieter Perschon Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedicated to Jenica, Gunnar, and Dacy Abstract Despite its growing popularity in books, film, games, fashion, and décor, a suitable definition for steampunk remains elusive. Debates in online forums seek to arrive at a cogent definition, ranging from narrowly restricting and exclusionary definitions, to uselessly inclusive indefinitions. The difficulty in defining steampunk stems from the evolution of the term as a literary sub-genre of science fiction (SF) to a sub-culture of Goth fashion, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) arts and crafts movements, and more recently, as ideological counter-culture. Accordingly, defining steampunk unilaterally is challenged by what aspect of steampunk culture is being defined. -

Readercon 20 Program Guide

readercon 20 KRW ©2009 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, twentieth edition readercon 20 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 9th–12th July 2009 Guests of Honor: Elizabeth Hand Greer Gilman Memorial Guest of Honor: Hope Mirrlees program guide Policies and Practical Information........................................................................1 Bookshop Dealers ...................................................................................................4 Readercon 20 Guest Index .....................................................................................5 Readercon 20 Program ...........................................................................................7 Thursday ...........................................................................................................7 Friday ................................................................................................................9 Saturday ..........................................................................................................20 Sunday.............................................................................................................27 Readercon 20 Committee .....................................................................................34 Readercon 21 Advertisement...............................................................................35 Program Participant Bios ....................................................................................37 Hotel Map.....................................................................Just