Directors in the Twilight Zone - Hungary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinball Game List

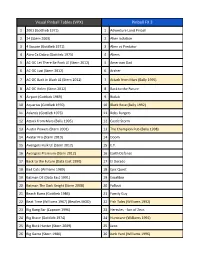

Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 1 Adventure Land Pinball 2 24 (Stern 2009) 2 Alien Isolation 3 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) 3 Alien vs Predator 4 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) 4 Aliens 5 AC-DC Let There Be Rock LE (Stern 2012) 5 American Dad 6 AC-DC Luci (Stern 2012) 6 Archer 7 AC-DC Back in Black LE (Stern 2012) 7 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 8 AC-DC Helen (Stern 2012) 8 Back to the Future 9 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) 9 Biolab 10 Aquarius (Gottlieb 1970) 10 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 11 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 11 Bobs Burgers 12 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 12 Castle Storm 13 Austin Powers (Stern 2001) 13 The Champion Pub (Bally 1998) 14 Avatar Pro (Stern 2010) 14 Doom 15 Avengers Hulk LE (Stern 2012) 15 E.T. 16 Avengers Premium (Stern 2012) 16 Earth Defense 17 Back to the Future (Data East 1990) 17 El Dorado 18 Bad Cats (Williams 1989) 18 Epic Quest 19 Batman DE (Data East 1991) 19 Excalibur 20 Batman The Dark Knight (Stern 2008) 20 Fallout 21 Beach Bums (Gottlieb 1986) 21 Family Guy 22 Beat Time (Williams 1967) (Beatles MOD) 22 Fish Tales (Williams 1992) 23 Big Bang Bar (Capcom 1996) 23 Hercules - Son of Zeus 24 Big Brave (Gottlieb 1974) 24 Hurricane (Williams 1991) 25 Big Buck Hunter (Stern 2009) 25 Jaws 26 Big Game (Stern 1980) 26 Junk Yard (Williams 1996) Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 27 Big Guns (Williams 1987) 27 Jurassic Park 28 Black Knight (Williams 1980) 28 Jurassic Park Pinball Mayhem 29 Black Knight 2000 (Williams 1989) 29 Jurassic World 30 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 30 Mars 31 Blue Note (Gottlieb 1979) 31 Marvel - Age of Ultron 32 Bram Stoker's Dracula (Williams 1993) 32 Marvel - Ant-Man 33 Bronco (Gottlieb 1977) 33 Marvel - Blade 34 Bubba the Redneck Werewolf (2018) 34 Marvel - Captain America 35 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1976) 35 Marvel - Civil War 36 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 36 Marvel - Deadpool 37 Bugs Bunny B. -

Into the Twilight Zone: Informing Judicial Discretion in Federal Sentencing

Ramirez 8.0 5/21/2009 2:14 PM INTO THE TWILIGHT ZONE: INFORMING JUDICIAL DISCRETION IN FEDERAL SENTENCING Mary Kreiner Ramirez* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Independence Versus Accountability: The Limits of Discretion in Sentencing .......................................................................................... 597 II. Influential Factors Shaping Discretionary Decisions ........................ 607 A. Appellate Review and Normative Forces ................................... 608 B. Bias and Diversity .......................................................................... 609 C. Political Process and the Judiciary ............................................... 614 D. Informing Federal Judges Through Judicial Education Programs ...................................................................... 617 III. Channeling Discretion Through Cognitive Training: Guiding Discretion ................................................................................ 621 A. Recent Science on Cognitive Studies .......................................... 624 B. External Guidance to Discretion: Effective Training and Mindfulness ............................................................................. 627 IV. Embracing Informed Discretion ......................................................... 635 A. Obstacles to Education ................................................................. 635 B. Finding the Tipping Point ............................................................. 637 V. Conclusion ............................................................................................ -

Directors in the Twilight Zone V Directors in the Twilight Zone V

DIRECTORS IN THE TWILIGHT ZONE V DIRECTORS IN THE TWILIGHT ZONE V Contributors Country Contributor/s Argentina Adolfo Rouillon University of Rosario Daniel F Alonso Austral University Australia Jeffrey Siddle Kara Thornton Isabel Coulton Macpherson Kelley Bahamas Simone I. Fitzcharles Marco M. Turnquest Lennox Paton Belgium Nora Wouters Bermuda John Riihiluoma John Wasty Jessica Almeida Appleby (Bermuda) Limited Canada The Hon. Regional Senior Justice Geoffrey Morawetz Ontario Superior Court of Justice Toronto Hon. James Farley Q.C. Retired Dr. Janis Sarra University of British Columbia Cathy Costa-Faria Jesse Mighton Goodmans LLP Toronto Cayman Islands Michael Pearson Stephen Briscoe FFP China Prof. Xianchu Zhang The University of Hong Kong Colombia Diana Lucia Talero Castro Fellow, INSOL International Urdaneta, Vélez, Pearl & Abdallah Abogados England and Wales Gordon Stewart Rupert Cheetham Allen & Overy LLP Estonia Dr. Leonid Tolstov TGS BALTIC Philipp Takjas Rechtsanwalt, Associated Partner, Noerr LLP vi DIRECTORS IN THE TWILIGHT ZONE V Country Contributor/s France Anker Sorensen De Gaulle Fleurance et Associés - Société d’Avocats Germany Dr. Bernd Meyer-Loewy Kirkland & Ellis International LLP Greece Orestis Omran Dentons Prof. Dr. Pavlos E. Masouros Masouros & Partners Hong Kong Richard Woodworth Viola Jing Alison Fok Allen & Overy India Prof. Vaneeta Patnaik WB National University of Juridical Science Indonesia Andi Kadir Hadiputranto Hadinoto & Partners (a member firm of Baker & McKenzie) Italy Giuseppe Scassellati Sforzolini -

Enter the Zone...THE TWILIGHT ZONE West Endicott Park Ross Park (Closed for Summer 2020) Recreation Park Highland Park George W

Enter the zone...THE TWILIGHT ZONE West Endicott Park West Park Ross Recreation Park Highland Park Johnson Park George W. CF Johnson Park “Everyone has to have a hometown... (Closed for Summer 2020) Binghamton’s Mine” -Rod Serling Rod Serling (1924-1975) Enter the SERLING zone (Limited Hours for Summer 2020) Binghamton Native, Writer, Producer, Teacher Rod Serling (1924-1975) graduated from Known primarily for his role as the host of Binghamton Central HS, Class of 1943. Now television’s The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling known as Binghamton High School, it is the had one of the most exceptional and varied home of the Rod Serling School of Fine Arts. careers in television. As a writer, a producer, Visit the plaque dedicated to Serling on the and for many years a teacher, Serling constantly front lawn, see the door casing where he signed challenged the medium of television to reach for his name in 1943 while working backstage, visit loftier artistic goals. the Helen Foley Theatre named after Rod’s drama After a brief career in radio, Serling entered television in 1951, penning teacher and mentor and where he was commencement speaker in 1968, scripts for several programs including Hallmark Hall of Fame and leaf through his high school yearbook at the library, or just stroll through Playhouse 90, at a time when the medium was referred to as “The the halls that Rod passed through each school day. Appointments are Golden Age.” suggested. Please contact Lawrence Kassan, Coordinator of Special Events In 1955, Kraft Television Theatre presented Serling’s teleplay Patterns and Theatre for the Binghamton City School District at (607) 762-8202. -

STINGER VP Virtual Pinball Machine

STINGER VP Virtual Pinball machine NewAgeArcade.com User Manual and Game list 863 Pinball Games in One I.PC Configuration Mainboard: Gigabyte H81 CPU: Intel G1840 RAM: 4GB Graphics Card:NVIDIA GT730 ,DDR5,1GB SSD:SAMSUMG 120 GB (or Sandisk or Intel) II.Monitor Requirement 1.Playfield monitor:1920*1080 (optimum resolution),connect to DVI of graphics card 2.Backglass monitor: 1366*768 (optimum resolution),connect to VGI of graphics card 3.DMD monitor:640*480 (Minimum resolution) ,connect to VGI of mainboard III.Buttons Layout 1 / 12 1. Left Flipper 2. Left MagnaSave 3. Left (game exploring),Left Tilt (game playing) 4. Right ( game exploring),Fwd Tilt (game playing) 5. PageLeft (game exploring),Right Tilt (game playing) 6. PageRight (game exploring),Mech Tilt (game playing) 7. Free play 8. Start game 9. Plunger 10. Exit 2 8 7 1 9 3 4 10 5 6 IV.These games release the ball by RMagnaSave ,LMagnaSave or LeftTilt key after starting. No. GameName No. GameName 1 Ali Baba (Gottlieb 1948) 17 Frolics (Bally 1952) 2 Alpine Club (Williams 1965) 18 Golden Arrow (Gottlieb 1977) 3 Ballyhoo (Bally 1969) 19 Happy Days (Gottlieb 1952) 4 Bank A Ball (Gottlieb 1965) 20 KC Jones (Gottlieb 1949) 5 Big Casino (Gottlieb 1961) 21 Lightning Ball (Gottlieb 1959) 6 Big Daddy (Williams 1963) 22 Mermaid (Gottlieb 1951) 7 Big Top (Gottlieb 1964) 23 Mystic Marvel (Gottlieb 1954) 8 Broadway (Bally 1952) 24 Palisades (Williams 1953) 2 / 12 9 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1948) 25 Queen of Hearts (Gottlieb 1952) 10 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 26 Silver (Gottlieb 1957) 11 Casino (Williams 1958) 27 Spitfire (Williams 1954) 12 Chinatown (Gottlieb 1952) 28 TeleCard (Gottlieb 1949) 13 Crosstown (Gottlieb 1966) 29 Ten Spot (Williams 1961) 14 De-Icer (Williams 1949) 30 Three Coins (Williams 1962) 15 Dragonette (Gottlieb 1954) 31 Three Deuces (Williams 1955) 16 FotoFinish (Gottlieb 1961) 32 Twin Bill (Gottlieb 1955) V.Games List No. -

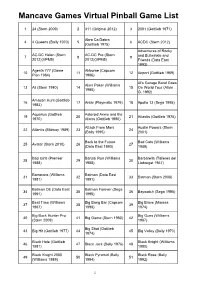

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List 1 24 (Stern 2009) 2 311(Original 2012) 3 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) AbraCa Dabra 4 4Queens( Bally 1970) 5 6 ACDC (Stern 2012) (Gottlieb 1975) Adventures of Rocky AC-DC Helen( Stern AC-DC Pro (Stern 7 8 9 and Bullwinkle and 2012)(VPM5) 2012)(VPM5) Friends (DataEast 1993) Agents777 (Game Airborne (Capcom 10 11 12 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) Plan 1984) 1996) Al's Garage Band Goes Alien Poker (Williams 13 Ali (Stern 1980) 14 15 On World Tour (Alivin 1980) G. 1992) Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 16 17 Antar (Playmatic 1979) 18 Apollo 13 (Sega 1995) 1983) Aquarius (Gottlieb Asteroid Annie andt he 19 20 21 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 1970) Aliens (Gottlieb 1980) Attack From Mars Austin Powers (Stern 22 Atlantis (Midway 1989) 23 24 (Bally 1995) 2001) Back to the Future Bad Cats (Williams 25 Avatar (Stern 2010) 26 27 (DataEast 1990) 1989) Bad Girls (Premier Banzai Run (Williams Barbarella( Talleres del 28 29 30 1988) 1988) Llobregat 1967) Barracora (Williams Batman (DataEast 31 32 33 Batman (Stern 2008) 1981) 1991) Batman DE (DataEast Batman Forever (Sega 34 35 36 Baywatch (Sega 1995) 1991) 1995) Beat Time (Williams Big Bang Bar (Capcom Big Brave (Maresa 37 38 39 1967) 1996) 1974) Big Buck Hunter Pro Big Guns (Williams 40 41 Big Game (Stern 1980) 42 (Stern 2009) 1987) Big Shot (Gottlieb 43 Big Hit (Gottlieb 1977) 44 45 Big Valley (Bally 1970) 1974) Black Hole (Gottlieb Black Knight (Williams 46 47 Black Jack (Bally 1976) 48 1981) 1980) Black Knight 2000 Black Pyramid (Bally Black Rose (Bally 49 50 51 (Williams 1989) 1984) 1992) -

In the Twilight Zone of Collaborative Disaster Prevention? the Experience of Flood Control in Different Levels of Government in Taiwan

Chinese Public Administration CPAR Review Volume 8 Issue 2, December 2017 In the Twilight Zone of Collaborative Disaster Prevention? The Experience of Flood Control in Different Levels of Government in Taiwan Ming-feng Kuo *, Chun-yuan Wang † * National Taiwan University, Taiwan † Central Police University, Taiwan With the coming of risk society, natural and human-made disasters have challenged the governance capacity of national and local governments. Although decentralization is a governance trend in various fields, little is known about the appropriate mode and crucial factors influencing its capacity for disaster management. The authors contend that a twilight zone exists between decentralization and centralization, and thus the purpose of this study is to explore how different levels of governments in Taiwan may collaborate in flood control effectively. By conducting in-depth interviews with public officials in Taiwan’s branches of flood control in central and local governments, we analyzed the existing conflicts of power and responsibility between central- and local authorities. We defined the factors that influence the construction of effective collaboration across the levels of governments. Based on our empirical findings, this study ultimately makes policy suggestions to facilitate the establishment of mechanisms for effective governance. Keywords: centralization, decentralization, collaborative disaster prevention, flood control, local governance, Taiwan INTRODUCTION in the act and the trend of decentralization has been confirmed in Taiwan, many controversies related to xamining how different levels of government power and responsibility have still emerged between have worked effectively and collaboratively central and local governments in the last two decades. Eduring disaster management has raised a big question and attracted considerable attention One of the most prominent cases in Taiwan is the dispute in academia and practice (Drabek, 1985; Kapucu, of flood control. -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

Pinball Game List

Pinball Game List 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 2 24 (Stern 2009) 3 250cc (Inder 1992) 4 300 (Gottlieb 1975) 5 311 (Original 2012) 6 4 Queens (Bally 1970) Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb ACDC - Devil Girl 7 8 9 AC-DC (Stern 2012) 1975) (Ultimate) (Stern 2012) AC-DC Helen (Stern Adam Strange (Original 10 11 AC-DC Pro (Stern 2012) 12 2012) 2015) Adventures of Rocky and Aerosmith (Original Agents 777 (Game Plan 13 Bullwinkle and Friends 14 15 2015) 1984) (Data East 1993) 16 Air Aces (Bally 1975) 17 Airborne (Capcom 1996) 18 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) Alien Dude (Original 19 Akira (Original 2011) 20 Ali (Stern 1980) 21 2013) Alien Poker (Williams Alien Racing (Original Alien Science (Original 22 23 24 1980) 2013) 2012) Aliens Infestation Aliens Legacy (Ultimate Alladin's Castle 25 26 27 (Original 2012) Edition) (Original (Ultimate) (Bally 1976) Alone In The Dark A2l0'1s1 )G arage Band Goes Amazing Spider-Man 28 29 30 (Original 2014) On World Tour (Alivin (Gottlieb 1980) Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb G. 1992) Angry Robot (Original 31 32 America's Most Haunted 33 1983) 2015) Aquarius (Gottlieb 34 Antar (Playmatic 1979) 35 Apollo 13 (Sega 1995) 36 1970) Arcade Mayhem (Original Asteroid Annie 37 38 Aspen (Brunswick 1979) 39 2012) (Gottlieb 1980) Asteroid Annie and the Atlantis (Gottlieb 40 41 42 Atlantis (Midway 1989) Aliens (Gottlieb 1980) 1975) Attack From Mars (Bally Attack of the Killer Attack Revenge FM 43 44 45 1995) Tomatoes (Original (Bally 1999) Austin Powers (Stern 2014) Back To The Future 46 47 Avatar (Stern 2010) 48 2001) (Original 2013) Back to the Future -

TZPT124 Five Characters

This is the first transcript of The Twilight Zone Podcast for hearing impaired fans of The Twilight Zone. Although perhaps “transcript” isn't quite the right term, as this document is actually the notes I make prior to recording the show, which I then read from. Instead of just deleting them each time as I have done for 100 plus episodes of The Twilight Zone Podcast, I hope they will be of some enjoyment to hearing impaired fans of the show. Please bear in mind that these notes are made for me to riff on and read from, so the style and cadence may be different from if they were written for an article, and much as I've tried to clean them up they may be rough round the edges in places. My apologies that I didn't do this sooner, but I hope you enjoy them now. Best Wishes – Tom Elliot Five Characters in Search of an Exit Introduction: Where are we? What are we? Who are we? Three questions that we've probably all asked at some point in our lives, perhaps not in the plural sense, but certainly in the singular. Where am I? What am I? Who am I? Why am I here? What am I doing with my life? Who am I supposed to be? We're seconds into this Twilight Zone Podcast and already things are getting kind of heavy. But in this case, how can we not be? It's always a bit of a balancing act with this show. The Twilight Zone has many levels. -

Buckaroo Banzai

FROM : Panasonic FAX SYSTEM PHONE NO. Jan. 07 1997 li:48fiM PI /sSf- ^. BUCKARQO BANZAI ,^&**V X ANCIENT SECRETS & NEW MYSTERIES ^ FROM : Panasonic FAX SYSTEM PHONE NO. : Jan. 07 1997 li:49flM P2 BUCKAROO BANZAI ANCIENT SECRETS & NEW MYSTERIES Revealed For Television Through The Discoveries Of Eari Mac Rauch & W.D. Richter Episode One "SUPERSIZE THOSE FRIES" Reported By Earl Mac Rauch THE FOX NETWORK FROM POLYGRAM TELEVISION AND THE BANZAI INSTITUTE FOR BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING AND STRATEGIC INFORMATION REVISED PTBST DRAFT December '99 07 1997 11:51fiM P1 FROM : Panasonic FAX SYSTEM PHONE NO. : Jan. ,#>"«. "SUPERSIZE THOSE FRIES" -Another Buckaroo Banzai Adventure- THE STUFF OF NIGHTMARES.. .GLOWING RED EYEBALLS, equal parts human and demonic/ pierce the darkness...hissing a hellish laugh from the backseat that becomes the SCREAM OF AN ENGINE AND SCREECHING TIRES, as we're OFF AND RUNNING IN THE WORLD- FAMOUS JET CAR—! Cold sweat dripping from the driver's brow: DR. BUCKAROO BANZAI, M.D., Ph.D., amazing Renaissance man of our time and the best-looking, too, in a sleek tuxedo, his right hand working a stick shift with a CADUCEUS on it...ENTWINED SNAKES, medicinal and sinister-looking at the same time... RED EYEBALLS Running from your shadow again, Banzai—? No matter where you go, there I am. Nothing like a little quality time inside your head, huh, Doc—? BUCKAROO BANZAI And the only reason for time is so everything doesn't happen all at once. ...as the amber digits on his HEADS-UP WINDSHIELD DISPLAY read 600 mph and climbing...BUCKAROO'S CAR PHONE SUDDENLY RINGING...as he jerks the wheel hard, taking his incredible speed machine around a corner and accelerating, dream like, through city traffic...his speaker phone barking.•• SPEAKER PHONE Dr. -

Maximales Spielvergnügen Inklusive Montage Minimaler Platzbedarf

Minimaler Maximales Inklusive Montage Platzbedarf Spielvergnügen Im eingeklappten Spielen Sie 76 Tische Direkte Montage bei Zustand hat der Flipper auf der Originalgröße Ihnen vor Ort. den vergleichbaren eines Widebody Es werden lediglich 6 Platzbedarf eines Flippers. Löcher in die Wand schmalen Heizkörpers. Weitere Flippertische gebohrt. in Steam beziehbar. Vor-Ort Service Ein Leben lang kostenlos Flippern ! Addams Family, The (Gold) Earthshaker! Medieval Madness Al’s Garage Band Goes On a World Tour Eight Ball Deluxe Monster Bash Attack from Mars El Dorado No Fear: Dangerous Sports Big Shot El Dorado: City Of Gold No Good Gofers Black Hole Elvira and the Party Monsters Party Zone, The Black Knight F-14 Tomcat PINBOT Black Knight 2000 Fireball Red & Ted’s Road Show Black Rose Firepower Rescue 911 Bone Busters Inc. Fish Tales Safe Cracker Bram Stoker’s Dracula Frank Thomas’ Big Hurt Scared Stiff Bride of PinBot (The Machine) FunHouse Space Shuttle Cactus Canyon Genie Star Trek: The Next Generation Cactus Jack’s Getaway: High Speed II, The Swords of Fury Centaur Gladiators Tales of the Arabian Nights Centigrade 37 Goin’ Nuts Taxi Central Park Gorgar Tee’d Off Champion Pub, The Haunted House Terminator 2: Judgment Day Cirqus Voltaire High Speed Theatre of Magic Class of 1812 Hurricane Twilight Zone Creature from the Black Lagoon Indianapolis 500 TX-Sector Cue Ball Wizard JackBot Victory Cyclone Jacks Open Whirlwind Diner Judge Dredd White Water Doctor Who Junk Yard WHO Dunnit Doctor Who: Master of Time Lights…Camera…Action! Xenon Dr. Dude and His Excellent Ray 4K Video Pinball 76 Tische 43 Zoll 4K Playfield Aufbau vor Ort Touchscreen Offenes System (Windows) Headtracking und Nudging Zotac I5 High End PC | RTX2060 | 16 GB RAM | 500 GB SSD | 500 GB HD | Windows 10 installiert ab 5999 € Reparaturservice.