Violence in South African Schools1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Department of Home Affairs [State of the Provinces:]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4825/department-of-home-affairs-state-of-the-provinces-104825.webp)

Department of Home Affairs [State of the Provinces:]

Highly Confidential Home Affairs Portfolio Committee PROVINCIAL MANAGER’S PRESENTATION BONAKELE MAYEKISO FREE STATE PROVINCE 6th SEPT 2011 Highly Confidential CONTENTS PART 1 Provincial Profile Provincial Management – Organogram Free State Home Affairs Footprint Provincial Capacity – Filled and Unfilled Posts Service Delivery Channels – Improving Access Corruption Prevention and Prosecution Provincial Finances – Budget, Expenditure and Assets PART 2 Strategic Overview Free State Turn-Around Times Conclusions 2 Highly Confidential What is unique about the Free State Free state is centrally situated among the eight provinces. It is bordered by six provinces and Lesotho, with the exclusion of Limpopo and Western Cape. Economic ¾ Contribute 5.5% of the economy of SA ¾ Average economic growth rate of 2% ¾ Largest harvest of maize and grain in the country. Politics ¾ ANC occupies the largest number of seats in the legislature Followed by the DA and COPE Safety and security ¾ The safest province in the country 3 Highly Confidential PROVINCIAL PROFILE The DHA offices are well spread in the province which makes it easy for the people of the province to access our services. New offices has been opened and gives a better image of the department. Municipalities has provided some permanent service points for free. 4 Highly Confidential PROVINCIAL MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE OPERATING MODEL 5 Highly Confidential Department of Home Affairs Republic of South Africa DHA FOOTPRINT PRESENTLY– FREE STATE Regional office District office 6 -

Botho/Ubuntu : Perspectives of Black Consciousness and Black Theology Ramathate TH Dolam University of South Africa, South Afri

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Botho/Ubuntu : Perspectives of Black Consciousness and Black Theology Ramathate TH Dolam University of South Africa, South Africa 0415 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract Botho/ubuntu is a philosophy that is as old as humanity itself. In South Africa, it was a philosophy and a way of life of blacks. It was an African cultural trait that rallied individuals to become communal in outlook and thereby to look out for each other. Although botho or ubuntu concept became popularised only after the dawn of democracy in South Africa, the concept itself has been lived out by Africans for over a millennia. Colonialism, slavery and apartheid introduced materialism and individualism that denigrated the black identity and dignity. The Black Consciousness philosophy and Black Theology worked hand in hand since the middle of the nine- teen sixties to restore the human dignity of black people in South Africa. Key words: Botho/Ubuntu, Black Consciousness, Black Theology, religion, culture. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org 532 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan 1. INTRODUCTION The contributions of Black Consciousness (BC) and Black Theology (BT) in the promotion and protection of botho/ubuntu values and principles are discussed in this article. The arrival of white people in South Africa has resulted in black people being subjected to historical injustices, cultural domination, religious vilification et cetera. BC and BT played an important role in identifying and analysing the problems that plagued blacks as a group in South Africa among the youth of the nineteen sixties that resulted in the unbanning of political organisations, release of political prisoners, the return of exiles and ultimately the inception of democracy. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

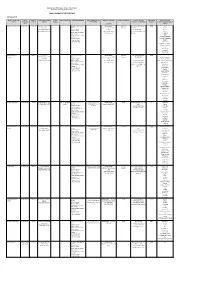

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Migration, Refugees, and Racism in South Africa

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Erasmus University Digital Repository Migration, Refugees, and Racism in South Africa Jeff Handmaker and Jennifer Parsley Abstract se penche sur la manière dont les actes des forces The paper looks at South Africa’s complex history and poli- policières et des fonctionnaires de l’état peut refléter les cies of racism, social separation and control and the impact sentiments du grand public, préjudiciant ainsi davan- that this has had on the nature of migration and refugee pol- tage les réfugiés et les immigrants. icy. The paper argues that this legacy has resulted in policy Les résultats de la CMCR (« Conférence mondiale and implementation that is highly racialized, coupled with a contre le racisme, la discrimination raciale, la xéno- society expressing growing levels of xenophobia. phobie et l’intolérance qui y est associée ») sont ex- Some causes and manifestations of xenophobia in South aminés et les gains obtenus en faveur des réfugiés et Africa are explored. It further examines how actions of police des demandeurs d’asile sont salués. Les implications and civil servants can mirror the sentiments of the general pour l’exécution (du programme d’actions) sont dis- public, further disadvantaging refugees and migrants. cutées à la lumière des attaques contre les États Unis. The outcomes of the WCAR are discussed with acknow- Pour conclure, l’article propose un certain nombre ledgment of the positive gains made for refugees and asylum de recommandations, dont la nécessité de mettre en seekers. The implications for implementation are debated in place des stratégies pour garder l’opinion publique light of the attacks on the USA. -

Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africaâ•Žs

Journal of Dispute Resolution Volume 2019 Issue 1 Article 16 2019 Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Benjamin Zinkel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin Zinkel, Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation, 2019 J. Disp. Resol. (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol2019/iss1/16 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dispute Resolution by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zinkel: Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth Apartheid and Jim Crow: Drawing Lessons from South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Benjamin Zinkel* I. INTRODUCTION South Africa and the United States are separated geographically, ethnically, and culturally. On the surface, these two nations appear very different. Both na- tions are separated by nearly 9,000 miles1, South Africa is a new democracy, while the United States was established over two hundred years2 ago, the two nations have very different climates, and the United States is much larger both in population and geography.3 However, South Africa and the United States share similar origins and histories. Both nations have culturally and ethnically diverse populations. Both South Africa and the United States were founded by colonists, and both nations instituted slavery.4 In the twentieth century, both nations discriminated against non- white citizens. -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

First Year Students' Narratives of 'Race' and Racism in Post-Apartheid South

University of the Witwatersrand SCHOOL OF HUMAN AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Department of Psychology First year students’ narratives of ‘race’ and racism in post-apartheid South Africa A research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Masters in Educational Psychology in the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, November 2011 Student: Kirstan Puttick, 0611655V Supervisor: Prof. Garth Stevens DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the Degree of Master in Educational Psychology at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. Kirstan Puttick November 2011 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several people whom I would like to acknowledge for their assistance and support throughout the life of this research project: Firstly, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my supervisor, Prof. Garth Stevens, for his guidance, patience and support throughout. Secondly, I would like to thank the members of the Apartheid Archive Study at the University of the Witwatersrand for all their direction and encouragement. Thirdly, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to all my friends and family who have been a tremendous source of support throughout this endeavour. I would also like to thank my patient and caring partner for all his kindness and understanding. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, I would like to thank my participants without whom this project would not have been possible. I cannot begin to express how grateful I am for the contributions that were made so willingly and graciously. -

Struggle for Liberation in South Africa and International Solidarity A

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERATION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY A Selection of Papers Published by the United Nations Centre against Apartheid Edited by E. S. Reddy Senior Fellow, United Nations Institute for Training and Research STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED NEW DELHI 1992 INTRODUCTION One of the essential contributions of the United Nations in the international campaign against apartheid in South Africa has been the preparation and dissemination of objective information on the inhumanity of apartheid, the long struggle of the oppressed people for their legitimate rights and the development of the international campaign against apartheid. For this purpose, the United Nations established a Unit on Apartheid in 1967, renamed Centre against Apartheid in 1976. I have had the privilege of directing the Unit and the Centre until my retirement from the United Nations Secretariat at the beginning of 1985. The Unit on Apartheid and the Centre against Apartheid obtained papers from leaders of the liberation movement and scholars, as well as eminent public figures associated with the international anti-apartheid movements. A selection of these papers are reproduced in this volume, especially those dealing with episodes in the struggle for liberation; the role of women, students, churches and the anti-apartheid movements in the resistance to racism; and the wider significance of the struggle in South Africa. I hope that these papers will be of value to scholars interested in the history of the liberation movement in South Africa and the evolution of United Nations as a force against racism. The papers were prepared at various times, mostly by leaders and active participants in the struggle, and should be seen in their context. -

Employing Sentiment Analysis for Gauging Perceptions of Minorities In

The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa ISSN: (Online) 2415-2005, (Print) 1817-4434 Page 1 of 1 Erratum Erratum: Employing sentiment analysis for gauging perceptions of minorities in multicultural societies: An analysis of Twitter feeds on the Afrikaner community of Orania in South Africa In the version of this article initially published, the text entries in Eqn 1 and Eqn 4 were mistakenly Authors: Eduan Kotzé1 misspelled which presented it in an illegible format. The actual values for Eqn 1 and Eqn 4 are Burgert Senekal2 updated and presented here: Affiliations: TP Precision ( p) = [Eqn 1] 1Department of Computer TP + FP Science and Informatics, University of the Free State, 2 ∗∗ (Recall Precision) South Africa Fm−=easure [Eqn 4] (Recall + )Precision 2Unit for Language Facilitation These corrections do not alter the study’s findings of significance or overall interpretation of the and Empowerment, University study results. The errors have been corrected in the PDF version of the article. The publisher of the Free State, South Africa apologises for any inconvenience caused. Corresponding author: Eduan Kotzé, [email protected] Date: Published: 21 Aug. 2019 How to cite this article: Kotzé, E. & Senekal, B., 2019, ‘Erratum: Employing sentiment analysis for gauging perceptions of minorities in multicultural societies: An analysis of Twitter feeds on the Afrikaner community of Orania in South Africa’, The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 15(1), a650. https://doi.org/ 10.4102/td.v15i1.650 Copyright: © 2019. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License. Read online: Scan this QR code with your smart phone or mobile device to read online. -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

Introduction to South Africa-India: Partnership in Freedom and Development

Introduction to South Africa-India: Partnership in freedom and development http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ESRINDP1B40002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Introduction to South Africa-India: Partnership in freedom and development Author/Creator Reddy, E.S. Date 1995 Resource type Articles Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) India, South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1900-1995 Source Enuga S. Reddy Description An article about the partnership between India and South Africa over the past decades and their common struggle for freedom. Format extent 15 pages (length/size) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ESRINDP1B40002 http://www.aluka.org INTRODUCTION TO SOUTH AFRICA-INDIA: PARTNERSHIP INTRODUCTION TO SOUTH AFRICA-INDIA: PARTNERSHIP IN FREEDOM AND DDEVELOPMENT, 19951 "I am convinced, your Excellency, that we are poised to build a unique and special partnership- a partnership forged in the crucible of history, common cultural attributes and common struggle". -

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District Socio�Economic Profile 2007 NO 1 and Development Plans

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile 2007 NO 1 and development plans Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans Centre for Development Support (IB 100) University of the Free State PO Box 339 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa www.ufs.ac.za/cds Please reference as: Centre for Development Support (CDS). 2007. Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans. CDS Research Report, Arid Areas, 2007(1). Bloemfontein: University of the Free State (UFS). CONTENTS I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. Geographic overview ........................................................................................................ 2 1. Namaqualand and Richtersveld ................................................................................................... 3 2. The Karoo................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Gordonia, the Kalahari and Bushmanland .................................................................................... 4 4. General characteristics of the arid areas ....................................................................................... 5 III. The Western Zone (Succulent Karoo) .............................................................................. 8 1. Namakwa District Municipality ..................................................................................................