Report Issue 13 2008–2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scribal Authorship and the Writing of History in Medieval England / Matthew Fisher

Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture Ethan Knapp, Series Editor Scribal Authorship and the Writing of History in SMedieval England MATTHEW FISHER The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, Matthew, 1975– Scribal authorship and the writing of history in medieval England / Matthew Fisher. p. cm. — (Interventions : new studies in medieval culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1198-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1198-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9299-0 (cd) 1. Authorship—History—To 1500. 2. Scribes—England—History—To 1500. 3. Historiogra- phy—England. 4. Manuscripts, Medieval—England. I. Title. II. Series: Interventions : new studies in medieval culture. PN144.F57 2012 820.9'001—dc23 2012011441 Cover design by Jerry Dorris at Authorsupport.com Typesetting by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and ITC Cerigo Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Abbreviations vi List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION 1 ONE The Medieval Scribe 14 TWO Authority, Quotation, and English Historiography 59 THREE History’s Scribes—The Harley Scribe 100 FOUR The Auchinleck Manuscript and the Writing of History 146 EPILOGUE 188 Bibliography 193 Manuscript Index 213 General Index 215 ABBrEviationS ANTS Anglo-Norman Text Society BL British Library CUL Cambridge University Library EETS Early English Text Society (OS, Original Series, ES, Extra Series, SS Supplementary Series) LALME A Linguistic Atlas of Late Medieval English, ed. -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

CURRICULUM Academic Year 2020 – 2021

CURRICULUM Academic year 2020 – 2021 DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT I to IV Semester M. Tech M.Tech in INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING (MIE) RAMAIAH INSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institute, Affiliated to VTU) BANGALORE – 54 About the Institute: Ramaiah Institute of Technology (RIT)(formerly known as M.S.Ramaiah Institute of Technology) is a self-financing institution established in Bangalore in the year 1962 by the industrialist and philanthropist, Late Dr. M S Ramaiah. The institute is accredited with “A” grade by NAAC in 2016 and all engineering departments offering bachelor degree programs have been accredited by NBA. RIT is one of the few institutes with prescribed faculty student ratio and achieves excellent academic results. The institute was a participant of the Technical Education Quality Improvement Program (TEQIP), an initiative of the Government of India. All the departments have competent faculty, with 100% of them being postgraduates or doctorates. Some of the distinguished features of RIT are: State of the art laboratories, individual computing facility to all faculty members. All research departments are active with sponsored projects and more than 304 scholars are pursuing PhD. The Centre for Advanced Training and Continuing Education (CATCE), and Entrepreneurship Development Cell (EDC) have been set up on campus. RIT has a strong Placement and Training department with a committed team, a good Mentoring/Proctorial system, a fully equipped Sports department, large air conditioned library withover1,35,427 books with subscription to more than 300 International and National Journals. The Digital Library subscribes to several online e-journals like IEEE, JET etc. RIT is a member of DELNET, and AICTE INDEST Consortium. -

Keeping Quality Teachers the Art of Retaining General and Special Education Teachers

Keeping Quality Teachers The Art of Retaining General and Special Education Teachers A Practical Guidebook for School Leaders Held Accountable for Student Success THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of The University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. .............................................. Tonawanda ADELAIDE L. SANFORD, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A., P.D. ........................ Hollis DIANE O’NEILL MCGIVERN,B.S.N., M.A., Ph.D. ...................................... Staten Island SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ............................................................ New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ............................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. .................................................................. North Syracuse MERRYL H. TISCH, B.A., M.A. ..................................................................... New York GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ................................................ Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. .............................................................. Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ........................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN, JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ..................... Albany LORRAINE A. CORTÉS-VÁZQUEZ,B.A., M.P.A. ........................................... Bronx JAMES R. TALLON, JR., B.A., M.A. ............................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. -

Technology Reference Guide for Radiologically Contaminated Surfaces

United States Office of Air and Radiation EPA-402-R-06-003 Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC 20460 March 2006 Technology Reference Guide for Radiologically Contaminated Surfaces Technology Reference Guide for Radiologically Contaminated Surfaces EPA-402-R-06-003 April 2006 Project Officer Ed Feltcorn U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air and Radiation Office of Radiation and Indoor Air Radiation Protection Division This page intentionally left blank. Technology Reference Guide for Radiologically Contaminated Surfaces U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air and Radiation Office of Radiation and Indoor Air Radiation Protection Division Center for Radiation Site Cleanup EnDyna, Inc. Under Contract No. 4W-2324-WTSZX This page intentionally left blank i Disclaimer This Technology Guide, developed by USEPA, is meant to be a summary of information available for technologies demonstrated to be effective for radioactive surface decontamination. Inclusion of technologies in this Guide should not be viewed as an endorsement of either the technology or the vendor by USEPA. Similarly, exclusion of any technology should not be viewed as not being endorsed by USEPA; it merely means that the information related to that technology was not so readily available during the development of this Guide. Also, the technology-specific performance and cost data presented in this document are somewhat subjective as they are from a limited number of demonstration projects and based on professional judgment. In addition, all images used in this document are from public domain or have been used with permission. ii Acknowledgments This manual was developed by the Radiation Protection Division of EPA’s Office of Radiation and Indoor Air. -

DAV UNIVERSITYJALANDHAR Course Scheme & Syllabus for B

DAV UNIVERSITY, JALANDHAR DAV UNIVERSITYJALANDHAR Course Scheme & Syllabus For B.Tech. in Mechanical Engineering (Hons./Pass) (Program ID- ) th 1st TO 8 SEMESTER Examinations 2013–2014 Session Syllabi Applicable For Admissions in 2013 Page 1 of 139 DAV UNIVERSITY, JALANDHAR Scheme of Courses B.Tech. in Mechanical Engineering Semester 1 Paper % Weightage S.No Course Title L T P Cr E Code A B C D Engineering 1 MTH152 4 1 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Mathematics-II 2 PHY151 Engineering Physics 3 0 0 3 25 25 25 25 75 Engineering Physics- 3 PHY152 0 0 2 2 20 80 50 Lab Basic Communication 4 ENG151 3 0 0 3 25 25 25 25 75 Skills Basic Communication 5 ENG152 0 0 2 2 20 80 25 Skills -Lab Electrical & 6 ELE101 Electronics 4 1 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Technology Electrical & 7 ELE102 Electronics 0 0 2 2 20 80 50 Technology -Lab General knowledge & 8 SGS102 2 0 0 2 25 25 25 25 50 Current affairs Fundamentals of 9 MEC102 Mechanical 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Engineering Manufacturing 10 MEC104 0 0 4 2 20 80 50 Practice 20 2 10 28 675 A: Continuous Assessment: Based on Objective Type Tests B: Mid-Term Test-1: Based on Objective Type & Subjective Type Test C: Mid-Term Test-2: Based on Objective Type & Subjective Type Test D: End-Term Exam (Final): Based on Objective Type Tests E: Total Marks L: Lectures T: Tutorial P: Practical Cr: Credits Page 2 of 139 DAV UNIVERSITY, JALANDHAR Scheme of Courses B.Tech. -

City of Miami Gardens

City of Miami Gardens D I S A B I L I T Y R E S O U R C E D I R E C T O R Y A Disclaimer: This database is maintained by the City of Miami Gardens and is provided as a courtesy by the City of Miami Gardens pursuant to the American’s with Disabilities Act. While the City of Miami Gardens attempts to make sure all information on the site has been secured from reliable sources; the City expressly disclaims any representation or warranty express or implied concerning the accuracy, completeness or fitness for a particular purpose of the information. Persons accessing this information assume full responsibility for the use of the information and understand and agree that the City is not responsible or liable for any claim, loss or damage arising from the use of the information. You are responsible for verifying all information and bear all risk for inaccuracies. Reference to specific providers, products, processes, or services do not constitute or imply recommendation or endorsement by the City of Miami Gardens or its employees. The views and opinions of the information contributors do not necessarily state or reflect those of the City. If you believe that any of the information contained herein is inaccurate or misleading, or if you would have to have your organization included, please send comments to: [email protected]/. 1 AARP (American Association of Retired Persons) AARP is the nation’s larges organization advocating for seniors. It offers a number of programs, materials and products for seniors. -

The Selection of Preferred Metric Values for Design and Construction NATIONAL BUREAU of STANDARDS

NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 990 \ 'fSAyi of U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/ National Bureau of Standards The Selection of Preferred Metric Values for Design and Construction NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is performed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government Agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference Materials; -

FDT Free Access

Jon Fauer ASC www.fdtimes.com Feb 2019 Issue 92 Art, Technique and Technology in Motion Picture Production Worldwide Vanja Černjul and Crazy Rich Asians Creative Solutions acquires Amimon Nicol Verheem, Ikigai, Art, Analogies Still Moving Pictures: The Favourite Greig Fraser, VICE, Arricam, Cooke Tour of Sony’s Atsugi Tech Center Sasaki & Cioni on Large Format CVP in the Camera Triangle RED Ranger for Rentals Sony VENICE 120 fps Panavision Lens Bar Tokina Vista Primes cmotion cPRO DJI Ronin-S Panther S-Type Dolly Transvideo Metadator Louma 2 Point & Plane ARRI ALEXA LF SUP 4.0 Sekonic C-800 Color Meter Preston Cinema Light Ranger 2W P+S Technik Evolution Anamorphic Cages for Pocket Cinema Camera 4K Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 4K Cooke Panchro/i Classics & FF Anamorphics Guillermo Granillo, ALEXA LF & ZEISS Supremes Cover: Awkwafina on Crazy Rich Asians with Panasonic VariCam. Photo courtesy of Warner Bros. www.fdtimes.com Art, Technique and Technology On Paper, Online, and now on iPad Film and Digital Times is the guide to technique and technology, tools and how-tos for Cinematographers, Photographers, Directors, Producers, Studio Executives, Camera Assistants, Camera Operators, Grips, Gaffers, Crews, Rental Houses, and Manufacturers. Subscribe It’s written, edited, and published by Jon Fauer, ASC, an award-winning Cinematographer and Director. He is the author of 14 bestselling books—over 120,000 in print—famous for their user-friendly way Online: of explaining things. With inside-the-industry “secrets-of the-pros” www.fdtimes.com/subscribe information, Film and Digital Times is delivered to you by subscription or invitation, online or on paper. -

"Puddie" RODGERS

newsletter VOL UME 9, NU~B ER 4 S UMME R 1982 P.O. Box 669, San Juan Capistrano, CA 92693 ©Oon & Carolyn Davis Ph: 714-496-9599 SYNERGETIC Working together; co-operating, co-operative SYNERGISM Co-operative action of discrete agencies such that the total effect is greater than the sum of the two effects taken independently. EXCHANGE OF IDEAS I met a man with a dollar I met a man with an idea We exchanged dollars We exchanged ideas I still had a dollar Now we each had two ideas SPHERICAL MAPPING FOR LOUDSPEAKER COVERAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PAGE 2 SYN·AUD-CON EDITORIAL 18 HP-41C CLUB 3 HIS SOUND - WORKSHEET 18 TIME 3 SMI LE 19 THRESHOLD HEARING VS HEARING AT HIGHER LEVELS ( 4 A PROGRESS REPORT ON TEP" 19 MASK - MUSICIAN'S AMPLIFICATION SOUND KONTR~LLER 4 MODEL QA-200 ELECTR- ACOUSTl C ANALYZER 20 DECIBEL REFERENCE LEVELS 5 A CONCERT HALL ACOUSTICS SEMINAR 20 PZr1'~ POOl UM 5 SYN-AUD-CON HOSPITALITY SUITE AT AES 20 HP-41C - DEAD BATTERIES 6 SYN-AUD-CON 1982 AND 1983 SCHEDULE 21 SAN FRANCISCO CLASS MONTAGE 6 NEWSLETTER UPDATE 22 LEDEm "DOWN UNDER" 6 THE FAILS MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE 23 A BREAKTHROUGH IN DIGITAL ADVERTISING 7 TE P" AND ACOUSTI C MODELS 23 AUDIO PORNOGRAPHY 7 SMILE 24 SPECIAL COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEMS 8 LEVELS AND TIME DIFFERENCES 25 FLYING ENGINEERS 9 PHASE DISTORTION & PHASE EQUALIZATION 26 MINNEAPOLIS CLASS ~ONTAGE 10 C.. A. "Puddie" RODGERS 27 CALCULATING PERCENTAGES AND RATIOS 10 THE INITIAL TIME DELAY GAP 27 FILTER BANDWIDTH DESIGNATIONS 11 "QUORUM" TELECONFERENCING MICROPHONE 28 FINDING THE "RENARD SERIES" FOR FRACTIONAL OCTAVE SPACING 11 NEW "HI-FI FAD?" - THE LEDETM LISTENING ROOM 28 CONVERTING ACOUSTIC REFERENCE LEVELS 12 THE "REVOLUTIONARY" COPERNICUS SPEAKER 28 SMILE 12 FROf1 THE LONDON FINANCIAL TIMES 29 WHEN TO VARY LW VERSUS Q TO CONTROL La 12 DIGITAL ADDITION CIRCUIT 29 HAROLD W. -

Industrial & Production Engineering

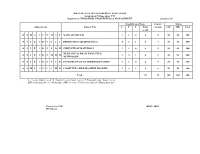

SCHEME OF TEACHING AND EXAMINATION 2010-2011 B.E INDUSTRIAL & PRODUCTION ENGINEERING III SEMESTER Teaching Hours / Sl. Subject Teaching week Examination No Code Title of the Subject Dept. Theory Pract IA Theory/ Total Pract. 1 10MAT31 Engineering Mathematics – III Maths 04 --- 03 25 100 125 2 10ME32A / Material Science & Metallurgy / ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 10ME 32B Mechanical Measurements & Metrology IM 3 10ME33 Basic Thermodynamics ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 IM 4 10ME34 Mechanics of Materials ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 IM 5 10ME 35 Manufacturing Processes-I ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 IM 6 10ME 36A / Computer Aided Machine Drawing/ Fluid ME/IP/ 01 03 03 25 100 125 10ME36B Mechanics IM 04 7 10MEL37A/ Metallography & Material Testing Lab/ ME/IP/ --- 03 03 25 50 75 10MEL 37B Mechanical Measurements & Metrology IM Lab 8 10MEL38A/ Foundry & Forging Laboratory/ Machine ME/IP/ --- 03 03 25 50 75 10MEL 38B Shop IM Total 21/24 09 - 200 700 900 1 SCHEME OF TEACHING AND EXAMINATION 2010-2011 B.E INDUSTRIAL & PRODUCTION ENGINEERING IV SEMESTER Teaching Hours / Sl. Subject Teaching week Examination No Code Title of the Subject Dept. Theory Pract Duration Marks (Hrs) IA Theory/ Total Pract. 1 10MAT41 Engineering Mathematics – IV Maths 04 --- 03 25 100 125 2 10ME42A / Material Science & Metallurgy / ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 10ME 42B Mechanical Measurements & IM Metrology 3 10ME43 Applied Thermodynamics IP/IM 04 --- 03 25 100 125 4 10ME44 Kinematics of Machines ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 IM 5 10ME 45 Manufacturing Processes-II ME/IP/ 04 --- 03 25 100 125 IM 6 10ME 46A / Computer Aided Machine ME/IP/ 01 --- 03 25 100 125 10ME46B Drawing/ Fluid Mechanics IM 04 7 10MEL47A/ Metallography & Material Testing ME/IP/ --- 03 03 25 50 75 10MEL 47B Lab/ Mechanical Measurements & IM Metrology Lab 8 10MEL48A/ Foundry & Forging Laboratory/ ME/IP/ --- 03 03 25 50 75 10MEL 48B Machine Shop IM Total 21/24 06 - 200 700 900 2 SCHEME OF TEACHING AND EXAMINATION 2010-2011 B.E INDUSTRIAL & PRODUCTION ENGINEERING V SEMESTER Teaching Sl. -

INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT Semester

BMS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, BANGALORE Autonomous College under VTU Department: INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT Semester: 03 Credit Hours/Week Contact Marks Subject Code Subject Title L T P Total hrs/wk CIE SEE Total credit 0 9 M A 3 I C M A T MATHAMATICS III 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 I E 3 D C P T 1 PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY-I 4 0 1 5 7 50 50 100 0 9 I E 3 D C S O M STRENGTH OF MATERIALS 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS & 0 9 I E 3 D C M M M 3 0 1 4 5 50 50 100 METROLOGY 0 9 I E 3 D C F T D FUNDAMENTALS OF THERMODYNAMICS 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 M I 3 G C C M D COMPUTER AIDED MACHINE DRAWING 2 0 2 4 6 50 50 100 Total 25 33 300 300 600 L – Lecture Hours / week; T- Tutorial Lecture Hours / week; P-Practical Lecture Hours / week. CIE- Continuous Internal Evaluation; SEE- Semester End Examination (of 3 Hours duration)‟ Chairperson-BOS HOD – IEM MI Cluster BMS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, BANGALORE Autonomous College under VTU Department: INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT Semester: 04 Credit Hours/Week Contact Marks Subject Code Subject Title L T P Total hrs/wk CIE SEE Total credits 0 9 I E 4 D C M A T ENGINEERING MATHEMATICS - IV 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 I E 4 D C P T 2 PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY-II 3 0 1 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 I E 4 D C T O M THEORY OF MACHINES 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 I E 4 D C M S M MATERIAL SCIENCE & METALLURGY 4 0 1 5 6 50 50 100 0 9 I E 4 D C M C D MACHINE DESIGN 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 0 9 I E 4 D C F M M FLUID MECHANICS & MACHINES 3 1 0 4 5 50 50 100 Total 25 31 300 300 600 L – Lecture Hours / week; T- Tutorial Lecture Hours / week; P-Practical Lecture Hours / week.