Breakthrough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE and GROUND-BASED OBSERVATIONS of the TYPE Iax SUPERNOVAE SN 2005Hk and SN 2008A

The Astrophysical Journal, 786:134 (19pp), 2014 May 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/786/2/134 C 2014. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE AND GROUND-BASED OBSERVATIONS OF THE TYPE Iax SUPERNOVAE SN 2005hk AND SN 2008A Curtis McCully1, Saurabh W. Jha1, Ryan J. Foley2,3, Ryan Chornock4, Jon A. Holtzman5, David D. Balam6, David Branch7, Alexei V. Filippenko8, Joshua Frieman9,10, Johan Fynbo11, Lluis Galbany12,13, Mohan Ganeshalingam8,14, Peter M. Garnavich15, Melissa L. Graham16,17,18,EricY.Hsiao18, Giorgos Leloudas11,19, Douglas C. Leonard20, Weidong Li8,29, Adam G. Riess21, Masao Sako22, Donald P. Schneider23, Jeffrey M. Silverman8,24,30, Jesper Sollerman11,25, Thea N. Steele8, Rollin C. Thomas26, J. Craig Wheeler24, and Chen Zheng27,28 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 136 Frelinghuysen Road, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; [email protected]. 2 Astronomy Department, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1002 West Green Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3 Department of Physics, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1110 West Green Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 4 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 5 Department of Astronomy, MSC 4500, New Mexico State University, P.O. Box 30001, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA 6 Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 7 Homer L. Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA 8 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411, USA 9 Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics and Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 10 Center for Particle Astrophysics, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, P.O. -

CFAIR2: NEAR INFRARED LIGHT CURVES of 94 TYPE IA SUPERNOVAE Andrew S

submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Supplements Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 05/12/14 CFAIR2: NEAR INFRARED LIGHT CURVES OF 94 TYPE IA SUPERNOVAE Andrew S. Friedman1,2, W. M. Wood-Vasey3, G. H. Marion1,4, Peter Challis1, Kaisey S. Mandel1, Joshua S. Bloom5, Maryam Modjaz6, Gautham Narayan1,7,8, Malcolm Hicken1, Ryan J. Foley9,10, Christopher R. Klein5, Dan L. Starr5, Adam Morgan5, Armin Rest11, Cullen H. Blake12, Adam A. Miller13, Emilio E. Falco1, William F. Wyatt1, Jessica Mink1, Michael F. Skrutskie14, and Robert P. Kirshner1 (Dated: July 23, 2018) submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Supplements ABSTRACT CfAIR2 is a large homogeneously reduced set of near-infrared (NIR) light curves for Type Ia super- novae (SN Ia) obtained with the 1.3m Peters Automated InfraRed Imaging TELescope (PAIRITEL). This data set includes 4637 measurements of 94 SN Ia and 4 additional SN Iax observed from 2005- 2011 at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona. CfAIR2 includes JHKs photometric measurements for 88 normal and 6 spectroscopically peculiar SN Ia in the nearby uni- verse, with a median redshift of z ∼ 0:021 for the normal SN Ia. CfAIR2 data span the range from -13 days to +127 days from B-band maximum. More than half of the light curves begin before the time of maximum and the coverage typically contains ∼ 13{18 epochs of observation, depending on the filter. We present extensive tests that verify the fidelity of the CfAIR2 data pipeline, including comparison to the excellent data of the Carnegie Supernova Project. CfAIR2 contributes to a firm local anchor for supernova cosmology studies in the NIR. -

A DEEP SEARCH for PROMPT RADIO EMISSION from THERMONUCLEAR SUPERNOVAE with the VERY LARGE ARRAY Laura Chomiuk1,11, Alicia M

Draft version July 1, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 A DEEP SEARCH FOR PROMPT RADIO EMISSION FROM THERMONUCLEAR SUPERNOVAE WITH THE VERY LARGE ARRAY Laura Chomiuk1;11, Alicia M. Soderberg2, Roger A. Chevalier3, Seth Bruzewski1, Ryan J. Foley4,5, Jerod Parrent2, Jay Strader1, Carles Badenes6 Claes Fransson7 Atish Kamble2, Raffaella Margutti8, Michael P. Rupen9, & Joshua D. Simon10 Draft version July 1, 2018 ABSTRACT Searches for circumstellar material around Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) are one of the most powerful tests of the nature of SN Ia progenitors, and radio observations provide a particularly sensitive probe of this material. Here we report radio observations for SNe Ia and their lower-luminosity thermonu- clear cousins. We present the largest, most sensitive, and spectroscopically diverse study of prompt (∆t . 1 yr) radio observations of 85 thermonuclear SNe, including 25 obtained by our team with the unprecedented depth of the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. With these observations, SN 2012cg joins SN 2011fe and SN 2014J as a SN Ia with remarkably deep radio limits and excellent temporal −1 _ −9 M yr coverage (six epochs, spanning 5{216 days after explosion, yielding M=vw . 5 × 10 100 km s−1 , assuming B = 0:1 and e = 0:1). All observations yield non-detections, placing strong constraints on the presence of circumstellar material. We present analytical models for the temporal and spectral evolution of prompt radio emission from thermonuclear SNe as expected from interaction with either wind-stratified or uniform density media. These models allow us to constrain the progenitor mass loss rates, with limits ranging _ −9 −4 −1 −1 from M . -

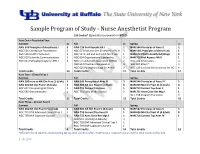

Sample Program of Study

Sample Program of Study - Nurse Anesthetist Program 126 Credits* (Specialty coursework in BOLD) Year One – Preclinical Year Summer Cr Fall Cr Spring Cr NAN 543 Principles of Anesthesia I 3 NAN 718 Prof Aspects NA I 1 NAN 544 Principles of Anes II 2 NGC 501 Conceptual Foundations 3 NGC 527 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC II 3 NAN 544L Principles of Anes II Lab 1 NGC 518 Health Promotion 3 NGC 527L Eval and Gen Evidence II Lab 1 NAN 672 Pharm Anesth/Adj Drugs 3 NGC 520 Scientific Communications 2 NGC 634 Organizational Leadership 3 NAN 719 Prof Aspects NA II 1 NGC 625 Pathophysiology for APN I 3 NGC 575 Adv Helth Assessmnt (CRNA) 2 NGC 502 Informatics 3 NGC 612 Pharmacotherapeutics 4 NGC 509 Ethics* 3 NGC 626 Pathophysiology for APN II 3 NGC 526 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC I 4 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 17 Total Credits 17 Year Two – Clinical Year I Summer Fall Spring NAN 598 Intro to NA Clin Prac (1 d/wk) 2 NAN 545 Principles of Anes III 3 NAN 546 Principles of Anes IV 3 NAN 601 NA Clin Pract I (3 d/wk) 6 NAN 602 NA Clin Pract II (4 d/wk) 8 NAN 603 NA Clin Pract III (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 632 Interpreting HC Policy 3 NAN 711 Current Top Anes 1 NAN 712 Current Top Anes II 1 NGC 692 Grantsmanship 1 NGC 701 State of the Science 3 NAN 721 Anes Crisis Res Mgt I 1 NGC 638 Program Evaluation 3 Total Credits 12 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 16 Year Three – Clinical Year II Summer Fall Spring NAN 604 NA Clin Pract IV (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 605 NA Clin Pract V (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 547 Principles of Anes V 3 NGC 725 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac I 2 NAN 713 Current Top Anes III 1 NAN 606 NA Clin Pract VI (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 798 DNP Capstone Course I 1 NAN 722 Anes Crisis Res Mgt II 1 NAN 714 Current Top Anes IV 1 NGC 533 Teaching in Nursing 3 NGC 726 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac II 2 NGC 799 DNP Capstone Course II 1 Total Credits 9 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 12 *Effective for all students matriculating Spring 2015 and thereafter, N509 is not a required course and the total credits will be 123. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

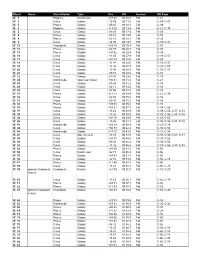

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

The Dichotomy of Seyfert 2 Galaxies: Intrinsic Differences and Evolution

A&A 570, A72 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424622 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics The dichotomy of Seyfert 2 galaxies: intrinsic differences and evolution E. Koulouridis Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens, 15236 Palaia Penteli Athens, Greece e-mail: [email protected] Received 17 July 2014 / Accepted 20 August 2014 ABSTRACT We present a study of the local environment (≤200 h−1 kpc) of 31 hidden broad line region (HBLR) and 43 non-HBLR Seyfert 2 (Sy2) galaxies in the nearby universe (z ≤ 0.04). To compare our findings, we constructed two control samples that match the redshift and the morphological type distribution of the HBLR and non-HBLR samples. We used the NASA Extragalactic Database (NED) to find all neighboring galaxies within a projected radius of 200 h−1 kpc around each galaxy, and a radial velocity difference δu ≤ 500 km s−1. Using the digitized Schmidt survey plates (DSS) and/or the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), when available, we confirmed that our sample of Seyfert companions is complete. We find that, within a projected radius of at least 150 h−1 kpc around each Seyfert, the fraction of non-HBLR Sy2 galaxies with a close companion is significantly higher than that of their control sample, at the 96% confidence level. Interestingly, the difference is due to the high frequency of mergers in the non-HBLR sample, seven versus only one in the control sample, while they also present a high number of hosts with signs of peculiar morphology. -

Joseph David Lyman

OBSERVATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROGENITORS OF SUPERNOVAE Joseph David Lyman ASTROPHYSICS RESEARCH INSTITUTE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. March 20, 2014 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pub- lished without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be ac- knowledged c J. D. Lyman 2013. ° ii Declaration The work presented in this thesis was carried out in the Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University. Unless otherwise stated, it is the original work of the author. Whilst registered as a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, for which submission is now made, the author has not been registered as a candidate for any other award. This thesis has not been submitted in whole, or in part, for any other degree. Joseph Lyman Astrophysics Research Institute Liverpool John Moores University Liverpool Science Park Brownlow Hill Liverpool L3 5RF UK iii OBSERVATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS OF THE PROGENITORS OF SUPERNOVAE JOSEPH DAVID LYMAN Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ASTROPHYSICS RESEARCH INSTITUTE October 2013 Abstract Supernovae (SNe) are the spectacular deaths of stars and have shaped the universe we see today. Their far-reaching influence affects the chemical and dynamical evolution of galaxies, star formation, neutron star and black hole formation, and they are largely responsible for most of the heavy elements that make up the universe, including around 90 per cent of the reader. They also provide laboratories of nuclear and particle physics far beyond what we can construct on Earth and act as probes of extreme density and energy. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

Box-And Peanut-Shaped Bulges: I. Statistics

A&A manuscript no. ASTRONOMY (will be inserted by hand later) AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 11 (11.05.2; 11.19.2; 11.19.7; 11.19.6) November 9, 2018 Box- and peanut-shaped bulges ⋆ I. Statistics R. L¨utticke, R.-J. Dettmar, and M. Pohlen Astronomisches Institut, Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum, D-44780 Bochum, Germany email: [email protected] Received 11 May 2000; accepted 14 June 2000 Abstract. We present a classification for bulges of a com- External cylindrically symmetric torques (May et al. plete sample of ∼ 1350 edge-on disk galaxies derived from 1985) or mergers of two disk galaxies (Binney & Petrou the RC3 (Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies, 1985, Rowley 1988) as origins of b/p bulges require very de Vaucouleurs et al. 1991). A visual classification of the special conditions (Bureau 1998). Therefore such evolu- bulges using the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) in three types tionary scenarios can explain only a very low frequency of of b/p bulges or as an elliptical type is presented and sup- b/p bulges. Accretion of satellite galaxies is a formation ported by CCD images. NIR observations reveal that dust process of b/p bulges (Binney & Petrou 1985, Whitmore & extinction does almost not influence the shape of bulges. Bell 1988), which could produce a higher frequency of b/p There is no substantial difference between the shape of bulges. However, an oblique impact angle of the satellite bulges in the optical and in the NIR. Our analysis reveals is needed for the formation of a b/p bulge and a mas- that 45% of all bulges are box- and peanut-shaped (b/p). -

Tri – Objektauswahl NGC

Tri – Objektauswahl NGC NGC 0579 NGC 0621 NGC 0735 NGC 0778 NGC 0816 NGC 0931 NGC 0978 NGC 0582 NGC 0634 NGC 0736 NGC 0780 NGC 0819 NGC 0940 NGC 0987 NGC 0587 NGC 0653 NGC 0738 NGC 0783 NGC 0826 NGC 0949 NGC 1002 NGC 0588 NGC 0661 NGC 0739 NGC 0784 NGC 0855 NGC 0953 NGC 1057 NGC 0592 NGC 0666 NGC 0740 NGC 0785 NGC 0860 NGC 0959 NGC 1060 NGC 0595 NGC 0669 NGC 0750 NGC 0789 NGC 0861 NGC 0968 NGC 1061 NGC 0598 NGC 0670 NGC 0751 NGC 0798 NGC 0865 NGC 0969 NGC 1066 NGC 0604 NGC 0672 NGC 0761 NGC 0804 NGC 0890 NGC 0970 NGC 1067 NGC 0608 NGC 0684 NGC 0769 NGC 0805 NGC 0917 NGC 0973 NGC 1093 NGC 0614 NGC 0688 NGC 0777 NGC 0807 NGC 0925 NGC 0974 Sternbild- Zur Objektauswahl: Nummer anklicken Übersicht Zur Übersichtskarte: Objekt in Aufsuchkarte anklicken Zum Detailfoto: Objekt in Übersichtskarte anklicken Tri Sternbildübersichtskarte Auswahl NGC 579_582_598_608_614 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 587_621_634_653 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 661_670_672_684 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 666_669_688_735 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 736_738_739_740_750_761 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl N 769_777_778_783_789_798_804 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 780_784_805_807_816_819 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 826_860 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 855_865 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 861 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 890_917_925_931_940 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 949_959_968_1002 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl NGC 953 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl N 969-70-73-74-78-87-1057-60-61-66-67-93 Aufsuchkarte Auswahl Auswahl NGC 579_582_608_614 ÜbersichtskarteNGC Aufsuch- karte Auswahl NGC 587_621 ÜbersichtskarteNGC Aufsuch- karte Auswahl NGC -

BS-DNP Nurse Anesthetist Sample Program Plan 124 Credits* (Specialty Coursework in BOLD)

BS-DNP Nurse Anesthetist Sample Program Plan 124 Credits* (Specialty coursework in BOLD) Year One – Preclinical Year Summer Cr Fall Cr Spring Cr NAN 543 Principles of Anesthesia I 3 NAN 718 Prof Aspects NA I 1 NAN 544 Principles of Anes II 2 NGC 518 Health Promotion 3 NGC 527 Eval and Gen Evidence for 4 NAN 544L Principles of Anes II Lab 1 NGC 520 Scientific Writing 2 HC II NAN 672 Pharm Anesth/Adj Drugs 3 NGC 625 Pathophysiology for APN I 3 NGC 634 Organizational Leadership 3 NAN 719 Prof Aspects NA II 1 NGC 576 Adv Health Assessment 3 NGC 612 Pharmacotherapeutics 4 NGC 502 Informatics 3 NGC 692 Grantsmanship 1 NGC 626 Pathophysiology for APN II 3 NGC 526 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC I 4 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 14 Year Two – Clinical Year I Summer Fall Spring NAN 598 Intro to NA Clin Prac (1 d/wk) 2 NAN 545 Principles of Anes III 3 NAN 546 Principles of Anes IV 3 NAN 601 NA Clin Pract I (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 602 NA Clin Pract II (4 d/wk) 8 NAN 603 NA Clin Pract III (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 632 Interpreting HC Policy 3 NAN 711 Current Top Anes 1 NAN 712 Current Top Anes II 1 NGC 501 Conceptual Foundations 3 NGC 701 State of the Science 3 NAN 721 Anes Crisis Res Mgt I 1 NGC 638 Program Evaluation 3 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 16 Year Three – Clinical Year II Summer Fall Spring NAN 604 NA Clin Pract IV (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 605 NA Clin Pract V (3 d/wk) 6 NAN 606 NA Clin Pract VI (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 725 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac 2 NAN 713 Current Top Anes III 1 NAN 714 Current Top Anes IV 1 I 1 NAN 722 Anes Crisis Res Mgt II 1 NGC 533 Teaching in Nursing 3 NGC 798 DNP Capstone Course I NAN 547 Principles of Anes V 3 NGC 726 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac II 2 NGC 799 DNP Capstone Course II 1 Total Credits 9 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 12 * This is a sample program plan. -

HB-NGC Index

Object Name Constellation Type Dec RA Season HB Page IC 1 Pegasus Double star +27 43 00 08.4 Fall C-21 IC 2 Cetus Galaxy -12 49 00 11.0 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 3 Pisces Galaxy -00 25 00 12.1 Fall C-39 IC 4 Pegasus Galaxy +17 29 00 13.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 5 Cetus Galaxy -09 33 00 17.4 Fall C-39 IC 6 Pisces Galaxy -03 16 00 19.0 Fall C-39 IC 8 Pisces Galaxy -03 13 00 19.1 Fall C-39 IC 9 Cetus Galaxy -14 07 00 19.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 10 Cassiopeia Galaxy +59 18 00 20.4 Fall C-03 IC 12 Pisces Galaxy -02 39 00 20.3 Fall C-39 IC 13 Pisces Galaxy +07 42 00 20.4 Fall C-39 IC 16 Cetus Galaxy -13 05 00 27.9 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 17 Cetus Galaxy +02 39 00 28.5 Fall C-39 IC 18 Cetus Galaxy -11 34 00 28.6 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 19 Cetus Galaxy -11 38 00 28.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 20 Cetus Galaxy -13 00 00 28.5 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 21 Cetus Galaxy -00 10 00 29.2 Fall C-39 IC 22 Cetus Galaxy -09 03 00 29.6 Fall C-39 IC 24 Andromeda Open star cluster +30 51 00 31.2 Fall C-21 IC 25 Cetus Galaxy -00 24 00 31.2 Fall C-39 IC 29 Cetus Galaxy -02 11 00 34.2 Fall C-39 IC 30 Cetus Galaxy -02 05 00 34.3 Fall C-39 IC 31 Pisces Galaxy +12 17 00 34.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 32 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.0 Fall C-39 IC 33 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.1 Fall C-39 IC 34 Pisces Galaxy +09 08 00 35.6 Fall C-39 IC 35 Pisces Galaxy +10 21 00 37.7 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 37 Cetus Galaxy -15 23 00 38.5 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 38 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 38.6 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 40 Cetus Galaxy +02 26 00 39.5 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 42 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 41.1 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC