• A Jewish Historian from Lublin אַ ייִדישע היסטאָריקערין פֿון לובלין

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust/Shoah the Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-Day Poland

NOW AVAILABLE remembrance a n d s o l i d a r i t y Holocaust/Shoah The Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-day Poland in 20 th century european history Ways of Survival as Revealed in the Files EUROPEAN REMEMBRANCE of the Ghetto Courts and Police in Lithuania – LECTURES, DISCUSSIONS, remembrance COMMENTARIES, 2012–16 and solidarity in 20 th This publication features the century most significant texts from the european annual European Remembrance history Symposium (2012–16) – one of the main events organized by the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity in Gdańsk, Berlin, Prague, Vienna and Budapest. The 2017 issue symposium entitled ‘Violence in number the 20th-century European history: educating, commemorating, 5 – december documenting’ will take place in Brussels. Lectures presented there will be included in the next Studies issue. 2016 Read Remembrance and Solidarity Studies online: enrs.eu/studies number 5 www.enrs.eu ISSUE NUMBER 5 DECEMBER 2016 REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY EDITED BY Dan Michman and Matthias Weber EDITORIAL BOARD ISSUE EDITORS: Prof. Dan Michman Prof. Matthias Weber EDITORS: Dr Florin Abraham, Romania Dr Árpád Hornják, Hungary Dr Pavol Jakubčin, Slovakia Prof. Padraic Kenney, USA Dr Réka Földváryné Kiss, Hungary Dr Ondrej Krajňák, Slovakia Prof. Róbert Letz, Slovakia Prof. Jan Rydel, Poland Prof. Martin Schulze Wessel, Germany EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Ewelina Pękała REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHER: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity ul. Wiejska 17/3, 00–480 Warszawa, Poland www.enrs.eu, [email protected] COPY-EDITING AND PROOFREADING: Caroline Brooke Johnson PROOFREADING: Ramon Shindler TYPESETTING: Marcin Kiedio GRAPHIC DESIGN: Katarzyna Erbel COVER DESIGN: © European Network Remembrance and Solidarity 2016 All rights reserved ISSN: 2084–3518 Circulation: 500 copies Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag. -

The Holocaust in Europe Research Trends, Pedagogical Approaches, and Political Challenges

Special Lessons & Legacies Conference Munich | November 4-7, 2019 The Holocaust in Europe Research Trends, Pedagogical Approaches, and Political Challenges CONFERENCE PROGRAM WELCOME TO MUNICH Since 1989, scholars from around the world are gathering biennially for the interdisciplinary conference "Lessons & Legacies of the Holocaust" to present their work and discuss new research trends and fresh pedagogical approaches to the history and memory of the Holocaust. This year, for the first time ever, a special Lessons & Legacies Conference takes place in Europe. The close proximity to historical sites and authentic places of Nazi rule and terror provides a unique opportunity not only to address the reverberations of the past in the present, but also to critically reflect upon the challenges for research and education posed by today’s growing nationalism and right-wing populism. What is more, our rich conference program includes a rare chance to visit relevant memorial sites, documentations centers, museums, and archives in the vicinity. We are especially pleased to collaborate with the Jewish Community of Munich and Upper Bavaria to introduce conference delegates to a vibrant Jewish communal life in the heart of the city and the region. We are looking forward to a productive and most fruitful conference that will stimulate debate and foster a lasting scholarly exchange among a large community of experts working in the field of Holocaust Studies. Center for Holocaust Studies at the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ) Leonrodstraße -

German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸Dykowski

Macht Arbeit Frei? German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939–1943 Witold Wojciech Me¸dykowski Boston 2018 Jews of Poland Series Editor ANTONY POLONSKY (Brandeis University) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: the bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-61811-596-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-61811-597-3 (electronic) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA P: (617)782-6290 F: (857)241-3149 [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com This publication is supported by An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61811-907-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. To Luba, with special thanks and gratitude Table of Contents Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Part One Chapter 1: The War against Poland and the Beginning of German Economic Policy in the Ocсupied Territory 1 Chapter 2: Forced Labor from the Period of Military Government until the Beginning of Ghettoization 18 Chapter 3: Forced Labor in the Ghettos and Labor Detachments 74 Chapter 4: Forced Labor in the Labor Camps 134 Part Two Chapter -

Pogrom Cries – Essays on Polish-Jewish History, 1939–1946

Rückenstärke cvr_eu: 39,0 mm Rückenstärke cvr_int: 34,9 mm Eastern European Culture, 12 Eastern European Culture, Politics and Societies 12 Politics and Societies 12 Joanna Tokarska-Bakir Joanna Tokarska-Bakir Pogrom Cries – Essays on Polish-Jewish History, 1939–1946 Pogrom Cries – Essays This book focuses on the fate of Polish “From page one to the very end, the book Tokarska-Bakir Joanna Jews and Polish-Jewish relations during is composed of original and novel texts, the Holocaust and its aftermath, in the which make an enormous contribution on Polish-Jewish History, ill-recognized era of Eastern-European to the knowledge of the Holocaust and its pogroms after the WW2. It is based on the aftermath. It brings a change in the Polish author’s own ethnographic research in reading of the Holocaust, and offers totally 1939–1946 those areas of Poland where the Holo- unknown perspectives.” caust machinery operated, as well as on Feliks Tych, Professor Emeritus at the the extensive archival query. The results Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw 2nd Revised Edition comprise the anthropological interviews with the members of the generation of Holocaust witnesses and the results of her own extensive archive research in the Pol- The Author ish Institute for National Remembrance Joanna Tokarska-Bakir is a cultural (IPN). anthropologist and Professor at the Institute of Slavic Studies of the Polish “[This book] is at times shocking; however, Academy of Sciences at Warsaw, Poland. it grips the reader’s attention from the first She specialises in the anthropology of to the last page. It is a remarkable work, set violence and is the author, among others, to become a classic among the publica- of a monograph on blood libel in Euro- tions in this field.” pean perspective and a monograph on Jerzy Jedlicki, Professor Emeritus at the the Kielce pogrom. -

Cultural History” Into the Study of the Holocaust: a Response to Dan Stone

Dan Michman Introducing more “Cultural History” into the Study of the Holocaust: A Response to Dan Stone In his paper, Dan Stone rightly observes that the study of the Holocaust is dominated to a large extent by the positivist approach, and within the latter by political and bureaucratic history which places a strong emphasis on facts recorded in archival documents. This type of research pays little attention to the theoretical issues of historical writing and their implications for modes of writing (as an exception to the rule, Stone mentions – and here, too, correctly – the uniqueness of Probing the Limits of Representation, edited by Saul Friedländer and published in 1992),1 at the same time as these theoretical issues were rocking the very foundations of other historical research.2 There were doubtless very good reasons for this. Firstly, there was the fact that the study both of the Germans (the “persecutors”) and of the Jews began already during the Holocaust and developed further immediately following the end of World War II, rather than being distanced by the passage of time. At that stage, the comprehensive picture was not yet clear so that at first, scholars had to gather laboriously, the basic details of the development of the event itself. This need arose once again in view of the spreading phenomenon of Holocaust denial during the 1990s and in the early years of the new millennium. In this context Christopher Browning observed on one occasion―following the Irving vs Lipstadt trial in London in 2000―that historians are charged with a responsibility “to get the facts right,” in order to silence the deniers. -

Children's Holocaust Testimonies

A Teaching Module for College and University Courses VOICES OF CHILD SURVIVORS: CHILDREN’S HOLOCAUST TESTIMONIES Module 2: Children in the Midst of Mass Killing Actions (Aktzyas) – Eastern Galicia Prepared with the generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, Inc. and the Rabbi Isra el Miller Fund for Shoah Education, Research and Documentation Joel Walters, Rita Horvath, Boaz Cohen, Keren Goldfrad Bar Ilan University 1 1 MODULE 2: Children in the midst of Mass Killing Actions (Aktzyas)—Eastern Galicia Table of Contents 1. Introduction Page 2 2. Eastern Galicia: Geography, Politics and History Page 4 3. Killing in Stages Page 6 4. An In-depth Analysis of a Child’s Testimony Page 13 5. Theoretical Significance Page 33 6. Additional Testimonies from Eastern Galicia Page 36 7. Supplement Page 52 2 2 MODULE 2: Children in the midst of Mass Killing Actions (Aktzyas)—Eastern Galicia 1. Introduction his educational module deals with testimonies of children from Jewish communities in Eastern Galicia – today the western Ukraine. TThese communities experienced pre-war Polish rule, the Soviet occupation from September 1939 to June 1941, and the German occupation from then on until liberation by the Soviet Army in 1944. During the time of German occupation, the Jewish population in the entire area was wiped out by the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators. Between the summer of 1941 and the winter of 1943, Galician Jews were subjected to three massive waves of killings resulting in the murder of more than 500,000 Jews out of the 600,000 who had resided there before the war.1 The surviving children were witness to periodically reoccurring waves of killing and terror, "Aktzyas" as they were called at the time, and their testimonies, presented in this teaching module, center around this experience. -

Post-War Soap Burial in Romania, Bulgaria and Brazil HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Joachim Neander Independent Researcher [email protected]

‘Symbolically burying the six million’: post-war soap burial in Romania, Bulgaria and Brazil HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Joachim Neander independent researcher [email protected] Abstract During the Second World War and its aftermath, the legend was spread that the Germans turned the bodies of Holocaust victims into soap stamped with the ini- tials ‘RIF’, falsely interpreted as ‘made from pure Jewish fat’. In the years following liberation, ‘RIF’ soap was solemnly buried in cemeteries all over the world and came to symbolise the six million killed in the Shoah, publicly showing the deter- mination of Jewry to never forget the victims. This article will examine the funerals that started in Bulgaria and then attracted several thousand mourners in Brazil and Romania, attended by prominent public personalities and receiving widespread media coverage at home and abroad. In 1990 Yad Vashem laid the ‘Jewish soap’ legend to rest, and today tombstones over soap graves are falling into decay with new ones avoiding the word ‘soap’. ‘RIF’ soap, however, is alive in the virtual world of the Internet and remains fiercely disputed between ‘believers’ and ‘deniers’. Key words: Jews, soap, burial, Brazil, Romania, Holocaust, RIF RIF and the ‘Jewish soap’ legend During the Second World War, the legend spread that the Germans boiled down the victims of the Holocaust to soap.1 Alleged proof were the letters ‘RIF’ stamped on all soap bars distributed in Germany and German occupied countries, misread as an abbreviation of Reines Juden-Fett or ‘pure Jewish fat’. In reality, RIF denoted Reichsstelle für Industrielle Fettversorgung, an authority that controlled the distri- bution and processing of fats for industrial purposes in wartime Germany.2 The legend originated in the ghettos of occupied Poland just after the beginning of the war as a kind of Jewish gallows humour. -

View the Conference Program

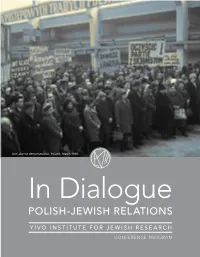

Anti-Zionist demonstration. Poland, March 1968. COVER PHOTO: Poland, March 1968, anti-Zionist demonstration. Signs read: “Popieramy klasę robotniczej Warszawy” [WE SUPPORT WARSAW’S WORKING CLASS] “Uczącym się chwała chuliganom pała” [GLORY TO STUDENTS, DOWN WITH HOOLIGANS] “Popieramy politykę pokoju i postępu” [WE SUPPORT THE POLITICS OF PEACE AND PROGRESS] “Zawsze z partią” [ALWAYS WITH THE PARTY] “Oczyścić partię ze syjonistów” [CLEANSE THE PARTY OF ZIONISTS] YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE MAY 5, 2019 CO-PRESENTED BY 1 his past year, tensions between the Polish government and the international Jewish community rose following a controversial law making it an offense T for anyone to accuse Poland of participating in the Holocaust or other Nazi crimes. According to the U.S. State Department, this law “could undermine free speech and academic discourse.” In this context, exploring the history of Polish-Jewish relations is more pertinent than ever. The 2018-2019 In Dialogue: Polish-Jewish Relations series explores the complex history of Poland, with its shifting borders, focusing in on a shared—but much misunderstood— past of Polish Jews and Christians. It provides historical and cultural tools to foster better understanding of Poland’s history, and of the tensions between history and memory, exclusion and belonging, national ideologies, identities, and antisemitism. The series culminates in this daylong conference on Sunday, May 5, discussing Polish- Jewish relations in the post-war era, including contemporary issues -

Newsletter FALL 2019

LOCATED IN THE CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY 15 West 16th Street New York, NY 10011-6301 yivo.org 212.246.6080 Newsletter FALL 2019 The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is dedicated to the preservation and study of the history and culture of East European Jewry worldwide. For nearly a century, YIVO has pioneered new forms of Jewish scholarship, research, education, and cultural expression. Our public programs and exhibitions, as well as online and on-site courses, extend our global outreach and enable us to share our vast resources. The YIVO Archives contains more than 23 million original items and YIVO’s Library has over 400,000 volumes—the single largest resource for such study in the world. Follow us @YIVOInstitute LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Contact tel 212.246.6080 Dear Friends, fax 212.292.1892 yivo.org On July 6, 2019, I received an award from the president of General Inquiries [email protected] Lithuania for YIVO’s work in the preservation of the prewar Archival Inquiries Jewish archives of Lithuania through the Edward Blank YIVO [email protected] Photo/Film Archives | [email protected] Vilna Online Collections project. I was proud to accept this Sound Archives | [email protected] award because it acknowledged the excellent collaboration Library Inquiries between YIVO and our Lithuanian partners. Importantly, it recognizes the value [email protected] of this work in helping to recover Lithuania’s Jewish past that can provide a Travel Directions foundation for building the kind of multicultural, liberal, and democratic soci- The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is located in the Center for Jewish History at 15 West 16th Street between Fifth and ety that many in Lithuania wish for their country. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Moshe Arens, Flags over the Warsaw Ghetto: The Untold Story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2011, 405 pages, (paperback). Review Article by Dariusz Libionka and Laurence Weinbaum “Whoever reports a saying in the name of its originator brings deliver- ance to the world.” [Rabbi Chanina] Babylonian Talmud, Megillah, 15a. The Warsaw Ghetto uprising was a seminal event in Jewish history and memory. Often compared to Masada or Thermopylae, no military encounter of comparable magnitude has attracted such a degree of attention. Over time, and especially in recent years, researchers have enabled us to develop a more accurate and nuanced understanding of this struggle and its context. Among the most elusive aspects of the uprising is the role played by the ad- herents of Vladimir Jabotinsky. In the 1930s, the New Zionist Organization (HaTzohar) and its youth movement, Betar, attracted a sizeable following in Po- land. Though bereft of most of its prewar leadership (including Menachem Be- gin), the remnants of this organization eventually established their own armed underground group in the Warsaw ghetto, the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW), which operated independently from the mainstream Jewish Fighting Organiza- tion (ŻOB). Led by Mordechai Anielewicz, the ŻOB was a coalition of left-wing Zionist youth movements as well as the anti-Zionist Bund and the Communists. Its best-known veterans were Zivia Lubetkin, Antek Zuckerman and Marek Edel- man, who, together with other surviving fighters, created the narrative upon which much of the popular knowledge of the uprising has been based. To the extent that the Revisionists figured in the accounts of their political rivals, it was referred to only minimally and sometimes disparagingly. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Relacje Ocalalych z Holocaustu (Sygn.301) Holocaust Survivor Testimonies RG‐15.084M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Tel. (202) 479‐9717 Email: [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Relacje Ocalalych z Holocaustu (Sygn.301) (Holocaust Survivor Testimonies) Dates: 1945‐1946 RG Number: RG‐15.084M Accession Number: 1997.A.0125 Creator: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma Extent: 14,588 digital images, JPEG (57.3 GB); 71 microfilm reels (35 mm) Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Languages: Polish, Yiddish, Hebrew, German, and Russian. Administrative Information Access: No restrictions on access. Reproduction and Use: Publication or copying of more than several documents for a third party requires the permission of the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny imienia Emanuela Ringelbluma. Preferred Citation: RG‐15.084M, Relacje Ocalalych z Holocaustu (Sygn. 301), 1945‐1946. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. Acquisition Information: Purchased from the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela 1 http://collections.ushmm.org http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Ringelbluma, Poland, Sygn. 302. Forms part of the Claims Conference International Holocaust Documentation Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. This archive consists of documentation whose reproduction and/or acquisition was made possible with funding from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Accruals: Accruals may have been received since this collection was first processed, see the Archives catalog at collections.ushmm.org for further information. -

Matters of Testimony

Introduction Matters of Testimony ••• Discoveries In February 1945, in the weeks after the liberation of Oświęcim by the 60th Army of the First Ukrainian Front, the massive complex of Auschwitz- Birkenau was proving difficult to manage. The Red Army, preoccupied with securing its position against German attempts to recapture the valuable industrial zone of Silesia, had few resources to spread across the camp’s multiple sites. The grounds of Birkenau were littered with debris and rubbish. Luggage lay in the cars of a train left on the unloading ramp, and was also strewn over the ground nearby. The departing SS had set fire to storehouses, and blown up the crematoria. The snow was beginning to melt, leaving everything in a sea of mud, and revealing more of what had been left behind: mass graves and burnt human remains. Around six hundred corpses had been found inside blocks or lying in the snow, and needed to be buried. Of the seven thousand prisoners who had been liberated on 27 January, nearly five thousand were in need of some kind of treatment. Soviet medical officers and Polish Red Cross volunteers came to the camp to care for them.1 Andrzej Zaorski, a 21-year-old doctor stationed in Kraków, was one of these volunteers. He arrived at Auschwitz a week or two after its liberation, where, as he recalled twenty-five years later, he was lodged in the commandant’s house. He found a richly illustrated book among the papers left behind. The author, an SS-man, described the birdlife in 2 • Matters of Testimony the vicinity of the camp, and thanked the commandant for permission to carry out observations.