A Dictionary of Malakmalak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) K-TEA (Achievement test) Kʻa-la-kʻun-lun kung lu (China and Pakistan) USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Karakoram Highway (China and Pakistan) K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) K-theory Ka Lae o Kilauea (Hawaii) USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) [QA612.33] USE Kilauea Point (Hawaii) K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) BT Algebraic topology Ka Lang (Vietnamese people) UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) Homology theory USE Giẻ Triêng (Vietnamese people) K9 (Fictitious character) NT Whitehead groups Ka nanʻʺ (Burmese people) (May Subd Geog) K 37 (Military aircraft) K. Tzetnik Award in Holocaust Literature [DS528.2.K2] USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) UF Ka-Tzetnik Award UF Ka tūʺ (Burmese people) K 98 k (Rifle) Peras Ḳ. Tseṭniḳ BT Ethnology—Burma USE Mauser K98k rifle Peras Ḳatseṭniḳ ʾKa nao dialect (May Subd Geog) K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 BT Literary prizes—Israel BT China—Languages USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 K2 (Pakistan : Mountain) Hmong language K.A. Lind Honorary Award UF Dapsang (Pakistan) Ka nō (Burmese people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Godwin Austen, Mount (Pakistan) USE Tha noʹ (Burmese people) K.A. Linds hederspris Gogir Feng (Pakistan) Ka Rang (Southeast Asian people) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris Mount Godwin Austen (Pakistan) USE Sedang (Southeast Asian people) K-ABC (Intelligence test) BT Mountains—Pakistan Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children Karakoram Range USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine K-B Bridge (Palau) K2 (Drug) Hukatere (N.Z.) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Synthetic marijuana Ka-taw K-BIT (Intelligence test) K3 (Pakistan and China : Mountain) USE Takraw USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test USE Broad Peak (Pakistan and China) Ka Tawng Luang (Southeast Asian people) K. -

Conference Abstracts

Keynote Abstracts Referential functions and the construction of prominence profiles Professor Petra Schumacher, University of Cologne (Monday, Dec 10th, 2 pm, H2-16) Referential expressions are essential ingredients for information processing. Speakers use particular referential forms to convey different discourse functions and thus shape the 'prominence profile' that organizes referents in discourse representation. The prominence profile, i.e. the ranking of the referential candidates, feeds into expectations for upcoming discourse referents and interacts with the choice of referential forms (e.g., less informative referential forms are more likely to refer to more prominent referents). The prominence profile can further be changed as discourse unfolds, i.e. certain referential expressions such as demonstratives can raise the prominence status of their referents. The talk discusses various cues that contribute to the dynamic construction of prominence profiles and presents evidence for the different referential functions from behavioral and event-related potential studies. Manifestations of complexity in grammar and discourse Professor Walter Bisang, University of Mainz (Wednesday, Dec 12th, 9 am, H2-16) Linguistic discussions on complexity come in various shades. Some models are based on cognitive costs and difficulty of acquisition, others look at the properties of the form by which grammatical distinctions are expressed and connected, yet another group of linguists focus on recursion and merge and, finally, complexity can be measured in terms of algorithmic information theory. What is common to the above approaches is their concentration on linguistic form. In my presentation, I argue that form is only one side of complexity. If one looks at complexity from the perspective of the two competing motivations of explicitness vs. -

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 Report submitted to the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in association with the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Front cover photo: Yipirinya School Choir, Northern Territory. Photo by Faith Baisden Disclaimer The Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents are not responsible for the activities of organisations and agencies listed in this report and do not accept any liability for the results of any action taken in reliance upon, or based on or in connection with this report. To the extent legally possible, the Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents, disclaim all liability arising by reason of any breach of any duty in tort (including negligence and negligent misstatement) or as a result of any errors and omissions contained in this document. The views expressed in this report and organisations and agencies listed do not have the endorsement of the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA). ISBN 0 642753 229 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices National Circuit CANBERRA ACT 2600 Or visit http://www.ag.gov.au/cca This report was commissioned by the former Broadcasting, Languages and Arts and Culture Branch of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS). -

Handbook of Kimberley Languages. Vol. I: General Information

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - No.I05 HANDBOOK OF KIMBERLEY LANGUAGES Vol ume 1: General Information William McGregor A project of the Kimberley Language Resource Centre Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY McGregor, W. Handbook of Kimberley languages. Vol. I: General information. C-105, xiv + 276 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1988. DOI:10.15144/PL-C105.cover ©1988 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. L PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of fo ur series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: SA Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, D.C. Laycock, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender H.P. McKaughan University of Hawaii University of Hawaii David Bradley P. Milhlhausler La Trobe University Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Gillian Sank off University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K. T'sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. -

Proto Gunwinyguan Verb Suffixes 11

Proto Gunwinyguan verb suffixes 11 BARRY ALPHER, NICHOLAS EVANS AND MARK HARVEY 1 Introduction I The study of paradigmatic irregularities is crucial to the genetic subclassification of languages, particularly in language families like Australian, where extensive diffusion of morphological items has sometimes taken place and where phonological conservatism often makes diffusion hard to trace. In Australian languages, conjugational irregularities of verbs, particularly in the suffixal systems encoding tense, aspect and mood (hereafter TAM),2 often appear to be the grammatical domain most resistant to borrowing. Even such intense cases of linguistic diffusion as those in eastern Arnhem Land (Heath 1978a), providing as they do evidence both of indirect typological diffusion and of occasional direct diffusion of case markers and pronominal enclitics, do not appear to result in the diffusion of verbal conjugational irregularities. The comparison of verbal inflectional paradigms was central to Alpher's (1972) study of the subgrouping of the languages of southwestern Cape York Peninsula, and Dixon (1980) again used verbal cO'njugations as prime evidence for the relatedness of Australian languages. Dixon's chapter on verbal reconstruction proposes that not only is it possible to reconstruct a small set of mostly monosyllabic verbs at the level of 'Proto Australian' (pA), but that it is also possible to reconstruct seven 'conjugation markers' upon which the Tense/AspectIMood (henceforth TAM) suffixes of pA and its descendants are based. Most of the evidence in Dixon (1980) for reconstructing seven pA conjugation markers comes from Pama-Nyungan (hereafter PN) languages.3 The only nonPN languages he considers are Kunwinjku (K), Ngandi (Ngan) and Rembarrnga (R) - all members of the Gunwinyguan (GN) family. -

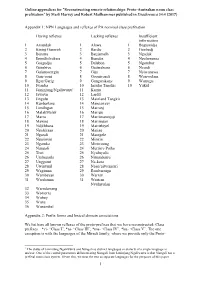

1 Appendix 1

Online appendices for “Reconstructing remote relationships: Proto-Australian noun class prefixation” by Mark Harvey and Robert Mailhammer published in Diachronica 34:4 (2017) Appendix 1: NPN Languages and reflexes of PA nominal class prefixation Having reflexes Lacking reflexes Insufficient information 1 Amurdak 1 Alawa 1 Bugurnidja 2 Bininj Gunwok 2 Bardic 2 Gonbudj 3 Burarra 3 Batjjamalh 3 Ngaduk 4 Enindhilyakwa 4 Bunuba 4 Ngalarrunga 5 Gaagudju 5 Dalabon 5 Ngombur 6 Giimbiyu 6 Gajirrabeng 6 Nyardi 7 Gulumoerrgin 7 Gija 7 Nyiwanawu 8 Gurr-goni 8 Gooniyandi 8 Worrwolam 9 Ilgar/Garig 9 Gungarakany 9 Wurrugu 10 Iwaidja 10 Insular Tangkic 10 Yukul 11 Jaminjung/Ngaliwurru1 11 Kamu 12 Jawoyn 12 Lardil 13 Jingulu 13 Mainland Tangkic 14 Kunbarlang 14 Mangarrayi 15 Limilngan 15 Marranj 16 MalakMalak 16 Marrgu 17 Marra 17 Marrimaninjsji 18 Mawng 18 Marringarr 19 Ndjébbana 19 Marrithiyel 20 Ngalakgan 20 Matige 21 Ngandi 21 Matngele 22 Ngarinyin 22 Minkin 23 Ngarnka 23 Miriwoong 24 Nungali 24 Murriny-Patha 25 Tiwi 25 Nyulnyulic 26 Umbugarla 26 Nimanburru 27 Unggumi 27 Na-kara 28 Uwinymil 28 Ngan’gityemerri 29 Wagiman 29 Rembarrnga 30 Wambayan 30 Warray 31 Wardaman 31 Western Nyulnyulan 32 Warndarrang 33 Worrorra 34 Wubuy 35 Wuna 36 Wunambal Appendix 2: Prefix forms and lexical domain associations We list here all known reflexes of the proto-prefixes that we have reconstructed: Class prefixes – *ci- “Class I”, *ta- “Class III”, *ma- “Class IV”, *ku- “Class V”. The one exception is with the languages of the Mirndi family, where we provide only the Proto- 1 The status of Jaminjung/Ngaliwurru and Nungali as distinct languages or dialects of a single language is unclear. -

A Sketch Grammar of Kamu Mark

A SKETCH GRAMMAR OF KAMU MARK HARVEY TABLE OF CONTENTS. Preface 1 Acknowledgements 2 Chapter 1 : Social Organisation of the Gamu People 3 1.1. Location and Contact History of the Gamu. 3 1.2. Consultant. 4 1.3. Neighbouring Languages and Linguistic Relationships. 5 1.4. Kinship 8 Chapter 2 : Phonology 13 2.1. The Phonemic Inventory 13 2.2. The Stop Contrast. 13 2.3. Retroflexion. 14 2.4. The Glottal Stop. 16 2.5. The Palatal Lateral. 18 2.6. The Apical Tap and Continuant. 18 2.7. Lenition. 19 2.8. Vowels 20 2.9. Diphthongs and Long Vowels. 22 2.10. Syllable and Morpheme Structures. 23 2.11. The Word 26 2.12. Stress 26 2.13. Orthography. 27 Chapter 3 : Nominals 29 3.1. Parts of Speech. 29 3.2. Nominal Stems 29 3.3. Nominal Classification. 31 3.4. Case Markers. 32 3.4.1. The Absolutive. 32 3.4.2. The Ergative/Instrumental. 33 3.4.3. The Dative. 34 3.4.4. The Allative. 35 3.4.5. The Locative. 36 3.4.6. The Ablative. 36 3.4.7. The Pergressive. 37 3.4.8. The Locational Cases. 38 3.4.9. The Comitative. 40 3.4.10. The Privative. 41 3.5. The Pronouns. 41 3.6. Definite Demonstratives. 45 3.7. Interrogative Demonstratives. 47 3.8. Temporals. 50 3.9. Quantifiers. 54 3.10. Other Nominal Affixes and Clitics. 55 3.11. The Order of Nominal Suffixes. 60 Chapter 4 : Verbs 61 4.1. The Verbal Complex 61 4.2. -

Download MIDDLE FLIGHT Vol.6 -2017

ISSN 2319-7684 MIDDLE FLIGHT SSM JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE UGC Approved National Level Peer Reviewed Journal NOVEMBER 2017 VOL. 6 NO. 1 SPECIAL VOLUME: Peripheral Identities in Literature, Film and Performance Middle Flight ISSN 2319-7684 Middle Flight SSM JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE VOL. 6 2017 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH S. S. MAHAVIDYALAYA KESHPUR, PASCHIM MEDINIPUR PIN: 721150, WEST BENGAL, INDIA Middle Flight SSM JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE UGC Approved National Level Peer Reviewed Journal Editorial Board: Bill Ashcroft, Australian Professorial Fellow, School of the Arts and Media, UNSW, Sydney Krishna Sen , Professor , University of Calcutta Tirthankar Das Purkayastha, Professor, Vidyasagar University Sankar Prasad Singha, Professor, Vidyasagar University Mahadev Kunderi, Professor, Mysore University Binda Sharma, Associate Professor, C.M.D. College (PG) Satyaki Pal , Associate Professor, R. K. M. Residential College (Autonomous), Narendrapur (PG) Goutam Buddha Sural , Professor, Bankura University Sudhir Nikam, Associate Professor, B. N. N. College (PG) Dinesh Panwar, Assistant Professor, University of Delhi Advisory Board: Jawaharlal Handoo, Professor, Tezpur University & President, Indian Folklore Congress Parbati Charan Chakraborty , Professor, The University of Burdwan B. Parvati, Professor, Andhra University Angshuman Kar, Associate Professor, The University of Burdwan Simi Malhotra, Professor, Jamia Millia Islamia University Shreya Bhattacharji, Associate Professor, Central University of Jharkhand Ujjwal Jana, Assistant Professor, Pondicherry University Subhajit Sengupta, Associate Professor, The University of Burdwan Guest Editor : Jaydeep Sarangi Editors : Debdas Roy Pritha Kundu Associate Editors : Joyjit Ghosh Indranil Acharya Published: November, 2017 ISSN: 2319 – 7684 Published by : Sukumar Sengupta Mahavidyalaya Keshpur, Paschim Medinipur, Pin: 721150 Ph: 03227-250861, Mail: [email protected] / [email protected] © S. -

The Spread of a Loan Word in Australian Languages

This item is Chapter 17 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Working verbs: the spread of a loan word in Australian languages Jane Simpson Cite this item: Jane Simpson (2016). Working verbs: the spread of a loan word in Australian languages. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 244-262 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2017 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 17 Working verbs: the spread of a loan word in Australian languages Jane Simpson Australian National University 1. Introduction1 From the first encounters with outsiders, Indigenous Australians developed words for expressing the new things, animals and concepts that came with the outsiders. This paper shows how the distribution of a single loanword ‘work’ and its variants across Australia sheds light on early contact between outsiders and Indigenous Australians, as well as between Indigenous Australians themselves. I propose that widespread multilingualism has led to diffusion both of forms and of strategies for integrating them morphologically into the grammars of individual languages.