The Bridge River 1 an Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Upper Bridge River Valley Official Community Plan Bylaw No. Bylaw 608, 1996

Upper Bridge River Valley Official Community Plan Bylaw No. Bylaw 608, 1996 CONSOLIDATED COPY May 2016 IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS IS AN UNOFFICIAL CONSOLIDATION OF BYLAW NO. 608 WHICH HAS BEEN PREPARED FOR CONVENIENCE ONLY. Although the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District is careful to assure the accuracy of all information presented in this consolidation, you should confirm all information before making any decisions based on it. Information can be confirmed through the SLRD Planning Department. Bylaw 608 ( Consolidated for Convenience Only) May 2016 SUMMARY OF AMENDMENTS CONSOLIDATED FOR CONVENIENCE ONLY Consolidated bylaws are consolidated for convenience only and are merely representative. Each consolidated bylaw consists of the original bylaw text and maps, together with current amendments which have been made to the original version. Copies of all bylaws (original and amendments) may be obtained from the SLRD Planning and Development Department. BY-LAW NO. DATE OF ADOPTION 1022 – 2006 Major Review of Upper Bridge River Valley OCP January 28, 2008 Rezoning a parcel of unsurveyed Crown land from Resource 1094 – 2008 October 26, 2009 Management to Industrial Tyax Real Estate Ltd. text and map amendments plus 1305 - 2014 housekeeping amendment July 28, 2014 PID 024-877-638 (Lot 5, DL 4931, Plan KAP67637, LLD) Creating a Medical Marihuana Production Facility 1309 - 2014 February 25, 2015 Development Permit Area 1440 - 2016 OCP amendments to the Tyax Staff Housing May 25, 2016 Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 608 Page 2 Bylaw 608 ( Consolidated for Convenience Only) May 2016 SQUAMISH LILLOOET REGIONAL DISTRICT BYLAW NO. 1022, 2006 A bylaw of the Squamish Lillooet Regional District to amend the Upper Bridge River Valley Official Community Plan Bylaw No. -

Horseshoe Bend Trail Rails & Trails Made Upofdeepsandand Es

Code: GC3QN7Z Rails & Trails Written and Researched by Wayne Robinson Horseshoe Bend Trail Site Identification Nearest Community: Lillooet, B.C. Geocache Location: N 50°51.608' W 122°09.318' Ownership: Crown Land Accuracy: 4 meters Photo: Wayne Robinson Overall Difficulty: 2.5 Overall Terrain: 3 The Horseshoe Bend is located on Highway 40, along the Bridge River just south of the confluence of the Bridge Access Information and and Yalakom Rivers. This is an interesting feature marked Restrictions: by a dramatic bend within the river. The canyon walls From the Mile 0 Cairn go north 2 km and turn left on Hwy 40 and follow for are laced with hoodoos and made up of deep sand and 28 km approximately to Horseshoe Bend gravel deposits left behind by retreating glaciers. At pull off. Do not drive down old road. first glance the Horseshoe Bend looks to be a marvel of Beware of cliff edge. Watch for falling geological forces, but it is a human made feature. This rock. Caution if with children and pets. Do not walk on upper rim of Horseshoe feature is sometimes called Horseshoe Wash; this helps Bend. describe the way in which the feature was created, through hydraulic mining for gold. It is amazing that this is a mine. Parking Advice: Operations began here in the 1908 and continued off and Between trees off the road at a natural on until relatively recent times. Between 1908 and 1914 view point. over a million dollars’ worth of gold was extracted from this area (using the historic gold value of $32 per ounce). -

British Columbia Geological Survey Geological Fieldwork 1989

GEOLOGY AND MINERAL OCCURRENCES OF THE YALAKOM RIVER AREA* (920/1, 2, 92J/15, 16) By P. Schiarizza and R.G. Gaba, M. Coleman, Carleton University J.I. Garver, University of Washington and J.K. Glover, Consulting Geologist KEYWORDS:Regional mapping, Shulaps ophiolite, Bridge REGIONAL GEOLOGY River complex, Cadwallader Group Yalakom fault, Mission Ridge fault, Marshall Creek fault. The regional geologic setting of the Taseko-Bridge River projectarea is described by Glover et al. (1988a) and Schiarizza et al. (1989a). The distributicn and relatio~uhips of themajor tectonostratigraphic assemblages are !;urn- INTRODUCTION marized in Figures 1-6-1 ;and 1-6-2. The Yalakom River area covers about 700 square kilo- The Yalakom River area, comprisinl: the southwertem metres of mountainous terrain along the northeastern margin segment of the project area, encompasses the whole OF the of the Coast Mountains. It is centred 200 kilometres north of Shubdps ultramafic complex which is interpreted by hagel Vancouver and 35 kilometresnorthwest of Lillooet.Our (1979), Potter and Calon et a1.(19901 as a 1989 mapping provides more detailed coverageof the north- (1983, 1986) dismembered ophiolite. 'The areasouth and west (of the em and western ShulapsRange, partly mapped in 1987 Shulaps complex is underlain mainly by Cjceanic rocks cf the (Glover et al., 1988a, 1988b) and 1988 (Schiarizza et al., Permian(?)to Jurassic €!ridge Rivercomplex, and arc- 1989d, 1989b). and extends the mapping eastward to include derived volcanic and sedimentary rocksof the UpperTri %sic the eastem part of the ShulapsRange, the Yalakom and Cadwallader Group. These two assemhkgesare struclurally Bridge River valleys and the adjacent Camelsfoot Range. -

Simon Fraser University Exchange / Study Abroad Fact Sheet: 2017/18

Simon Fraser University Exchange / Study Abroad Fact Sheet: 2017/18 GENERAL INFORMATION _________________________________________________ About SFU Simon Fraser University was founded 50 years ago with a mission to be a different kind of university – to bring an interdisciplinary rigour to learning, to embrace bold initiatives, and to engage deeply with communities near and far. Our vision is to be Canada’s most community-engaged research university. Today, SFU is Canada’s leading comprehensive research university and is ranked one of the top universities in the world. With campuses in British Columbia’s three largest cities – Vancouver, Burnaby and Surrey – SFU has eight faculties, delivers almost 150 programs to over 35,000 students, and boasts more than 130,000 alumni in 130 countries around the world. SFU is currently ranked as Canada’s top comprehensive university (Macleans 2017 University Rankings). The QS 2015 rankings placed SFU second in Canada for the international diversity of its students and for research citations per faculty member. For more, see: <www.sfu.ca/sfu-fastfacts> Campus Locations Simon Fraser University’s three unique campuses, spread throughout Metropolitan Vancouver, are all within an hour of one another by public transit. Burnaby (main campus): Perched atop Burnaby Mountain, Simon Fraser University’s original Arthur Erickson-designed campus now includes more than three dozen academic buildings and is flanked by UniverCity, a flourishing sustainable residential community. Surrey: A vibrant community hub located in the heart of one of Canada’s fastest-growing cities. Vancouver: Described by local media as the “intellectual heart of the city”, SFU’s Vancouver Campus transformed the landscape of urban education in downtown Vancouver. -

British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority

BRITISH COLUMBIA HYDRO AND POWER AUTHORITY Financial Information Act Return for the Year Ended March 31, 2016 Published in accordance with the Financial Information Act, Revised Statutes of British Columbia 1996, Chapter 140, as amended. FINANCIAL INFORMATION ACT RETURN FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Audited Consolidated Financial Statements F2016 B. British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority and its subsidiary Powerex Corp. Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – Board of Directors C. British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – General Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – Employees Schedule of Payments to Suppliers for Goods and Services Statement of Grants and Contributions D. Columbia Hydro Constructors Ltd. Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – General Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – Employees Schedule of Payments to Suppliers for Goods and Services E. Powerex Corp. Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – General Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – Employees Schedule of Payments to Suppliers for Goods and Services F. Powertech Labs Inc. Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – General Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses – Employees Schedule of Payments to Suppliers for Goods and Services British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority MANAGEMENT REPORT The consolidated financial statements of British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro) are the responsibility of management and have been prepared in accordance with the financial reporting provisions prescribed by the Province of British Columbia pursuant to Section 23.1 of the Budget Transparency and Accountability Act and Section 9.1 of the Financial Administration Act (see Note 2(a)). The preparation of financial statements necessarily involves the use of estimates which have been made using careful judgment. -

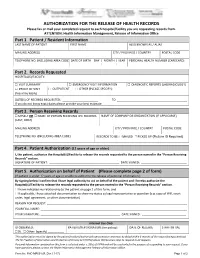

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

The British Columbia Road Runner, Volume 14, Number 1

THE BRITISH COLUMBIA ISSN UJ!>2 -2Hl Runner PBUSHED BY T H E 1 INISTRY OF HIGHWAYS AND P UBLIC W O K WINTER 1977 VOLUME 14, NUMBE R 1 LANGFORD FABRICATION SHOP As earl y as 1958, development of a single-operator winter unit was considered imperative. Such a unit , fully con tro llable from the cab, had to be capable of sanding and ploughing as well as retaining its original fu nctio n as a dump truck. By 1960, Langford was in production of hydraulic systems, underbody ploughs and tailgate sanders. The basic hydraulic system has been improved during the intervening years but it still uses the same components. Improvements in design and function have developed the unde rbody plough and pres ent L. E. Croft demand is for a plough for each new unit. Changes Art Cook have also been made through the years to the tail gat e sander , which now is widel y used in salt delivery. However, the ori ginal design was sound and, the quality and durability of the sanders proven. The or iginal sanders produced in 1960 are still performing from Langford to 100 Mile Hou se. Over 700 sanders have been produced as well as hundreds of underbody ploughs and hydraul ic systems. Langford fabrication sho p has been the chief manufacturing centre over the years. The hydraulic systems, underbody ploughs, and front-plough mou nts for all new units are fabricated and, excep t fo r the tandem truc ks, are ship ped out fo r installation. Each tandem unit has a front-plough mount, an underbody plough , and a hydraulic system tailor made and installed in the fab ricat ion sho p. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

November 2010 Elders Voice

Volume 10 Issue 12 ATTENTION: Elders Contact People Please Remember To Make Copies of The November 2010 EV Each Month For Your Elders And If EV’S 120th Issue! You Could Also Make Copies For Your Chiefs and Councils That Would Be A Great Help, And Much Appreciated! ______________________________________________________________ THE DATES ARE ANNOUNCED!! Hosts: Sto:lo and Coast Salish 35th Annual BC Elders Gathering July 12, 13, 14, 2011 LOCATION: The Fraser Valley Trade & Exhibition Centre or Tradex 1190 Cornel Street, Abbotsford _____________________________________________________________ HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO ALL ELDERS BORN IN NOVEMBER !! _____________________________________________________ SPECIAL THANKS TO THE 1ST PARTICIPANTS IN: ‘HAVE A FUNDRAISER FOR THIS ELDER’S OFFICE EVENT’ 1. Shirley Matilpi, BC Elders Council & the Namgis Elder`s Group - $200 2. Deanna George, BC Elders Council & the Tsleil-Waututh Nation- $250 3. Grace Charest, BC Elders Council & the Weiwaikum First Nation$100 *BC Elders Council Members and their support people will be conducting 50/50 draws/raffles in local communities to help fundraise for the BCECCS. Your support is appreciated. **Any group who does not yet have a member on the BC Elders Council is encouraged to contact this elder’s office. LEST WE FORGET - NOVEMBER 11th Pg. 9: Winter Family Gathering Tradi- Inside this issue tional Pow Wow Easy Bakers Corner/Handy 2 Pgs. 10-11: Dream Fund Bursary Info Tips/Website Information Pg. 12: Minister of Children and Fam- ily Development Opinion - Editorial List of Paid Support Fees 3 Pgs. 13-15: Aboriginal Childhood Dev. Pg. 16: Gladue Training Workshop KINGCOME INLET FLOODED 4 Pgs. 17-18: Gladue Workshop Info Pg. -

The Return of Cultural Burning | Scott Falconer

The Return of Cultural Burning | Scott Falconer The Lord Mayor’s Bushfire Appeal Churchill Fellowship Report: The Return of Cultural Burning Scott Falconer 2017 Churchill Fellow 1 The Return of Cultural Burning | Scott Falconer THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA Report by Scott Falconer 2017 Churchill Fellow THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA Project Description: The LordI understand Mayor’s thatBushfire the Churchill Appeal Trust Churchill may publish Fellowship this Report, to create either close in hard partnerships copy or on thewith internet and or employmentboth, and for consent Traditional to such Owners publication. in fire and land management. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against any loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the Trust in respect of or arising out of the publication of any Disclaimer:Report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I understandI also warrant that the that Churchill my Final ReportTrust may is original publish and this does report, not infringe either the in copyrighthard copy of or any on person, the internet, or both, orand contain consent anything to such which publication. is, or the incorporation of which into the Final Report is, actionable for defamation, a breach of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, I indemnify the Churchill Trust against loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or passing-off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. proceedings made against the trust in respect of or arising out of the publication of any report submitted to the trust and which the trust places on the website for access over the internet.