The Regulation and Supervision of the Belgian Financial System (1830 - 2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growth of Central Banking: the Societe Generale Des Pays-Bas And

Growth of Central Banking: The Soci•t• Ge•e•rale des Pays-Bas and the Impact of the Function of General State Cashier on Belgium's Monetary System (1822-1830) Julienne M. Laureyssens University of Manitoba I intend to reexamine in this paper the creation and the first ten odd years of operation of Belgium's first corporate bank, the SocaeteG(n•rale des Pays-Bas,with special regard to its function as General State Cashier. The bank was founded in 1822 by King William I of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. It was the only corporate bank in the southern part of the Netherlands until 1835. During the Dutch period, which lasted until September 1830 and up to the creation of the National Bank of Belgium in 1850, it carried out some of the functions of a central bank. King William I had an extensive knowledge of financial affairs, in fact, they were his private passion. According to Demoulin, he consideredbanks to be "des creatmns para-•'ta- tiques," institutions that are the state's "helpmates" whether they are owned and managed privately or not. The bank's particular function within the spectrum of the state's tasks were to mobilize BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC HISTORY., Second Series, Volume Fourteen, 1985. Copyright (c) 1985 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Library of Congress Catalog No. 85-072859. 125 126 capital and to extend the benefits of credit. William I was a firm believer in paper money, in the beneficial use of a wide variety of paper debt instruments, and in low interest rates. -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Financial Stability Report 2019

2019 Report Financial Stability National Bank of Belgium FINANCIAL STABILITY REPORT 2019 Financial Stability Report 2019 © National Bank of Belgium All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or part of this publication for educational and non‑commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. Contents Executive summary 7 Macroprudential Report 9 A. Introduction 9 B. Main risks and points for attention and prudential measures adopted 10 Financial Stability Overview 43 Banking sector 43 Insurance sector 68 Additional charts and tables for the banking and insurance sector 80 Thematic articles 89 Transaction-level data sets and monitoring of systemic risk : an illustration with Securities Holding Statistics 91 Climate-related risks and sustainable finance. Results and conclusions from a sector survey 107 A risk dashboard for detecting and monitoring systemic risk in Belgium 129 Statistical Annex 149 5 Executive summary 1. In the current macro-financial context, monitoring financial stability risks continues to be of great importance. In addition to the growing relevance for financial stability of a range of structural trends and risks – such as the intensive digitisation of the financial sector or risks related to climate change – the macro-financial impact of a persistent low interest rate environment is becoming increasingly apparent. Although a highly accommodative monetary policy on the part of the ECB is justified, given the current macroeconomic situation, the acceleration of the credit cycle in many EU countries, including Belgium, is an important warning that such a policy can also have adverse spillover effects and present potential risks to financial stability. The build‑up of vulnerabilities in Belgium in the form of an increasing debt ratio of households and companies or rising exposure of the financial sector to undervalued or under-priced financial risks may, in the long term, affect the resilience and absorption capacity of the Belgian economy in the event of major shocks. -

Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.P.A

Important Notice The Depository Trust Company B #: 15497-21 Date: August 24, 2021 To: All Participants Category: Tax Relief, Distributions From: International Services Attention: Operations, Reorg & Dividend Managers, Partners & Cashiers Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. CUSIPs: 46115HAU1 Subject: Record Date: 9/2/2021 Payable Date: 9/17/2021 CA Web Instruction Deadline: 9/16/2021 8:00 PM (E.T.) Participants can use DTC’s Corporate Actions Web (CA Web) service to certify all or a portion of their position entitled to the applicable withholding tax rate. Participants are urged to consult TaxInfo before certifying their instructions over CA Web. Important: Prior to certifying tax withholding instructions, participants are urged to read, understand and comply with the information in the Legal Conditions category found on TaxInfo over the CA Web. ***Please read this Important Notice fully to ensure that the self-certification document is sent to the agent by the indicated deadline*** Questions regarding this Important Notice may be directed to Acupay at +1 212-422-1222. Important Legal Information: The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”) does not represent or warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the information contained in this communication, which is based in part on information obtained from third parties and not independently verified by DTC and which is provided as is. The information contained in this communication is not intended to be a substitute for obtaining tax advice from an appropriate professional advisor. In providing this communication, DTC shall not be liable for (1) any loss resulting directly or indirectly from mistakes, errors, omissions, interruptions, delays or defects in such communication, unless caused directly by gross negligence or willful misconduct on the part of DTC, and (2) any special, consequential, exemplary, incidental or punitive damages. -

Download (PDF)

Review essay : Central banking through the centuries Working Paper Research by Ivo Maes October 2018 No 345 Editor Jan Smets, Governor of the National Bank of Belgium Statement of purpose: The purpose of these working papers is to promote the circulation of research results (Research Series) and analytical studies (Documents Series) made within the National Bank of Belgium or presented by external economists in seminars, conferences and conventions organised by the Bank. The aim is therefore to provide a platform for discussion. The opinions expressed are strictly those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. Orders For orders and information on subscriptions and reductions: National Bank of Belgium, Documentation - Publications service, boulevard de Berlaimont 14, 1000 Brussels Tel +32 2 221 20 33 - Fax +32 2 21 30 42 The Working Papers are available on the website of the Bank: http://www.nbb.be © National Bank of Belgium, Brussels All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. ISSN: 1375-680X (print) ISSN: 1784-2476 (online) NBB WORKING PAPER No. 345 – OCTOBER 2018 Abstract Anniversaries are occasions for remembrance and reflections on one’s history. Many central banks take the occasion of an anniversary to publish books on their history. In this essay we discuss five recent books on the history of central banking and monetary policy. In these volumes, the Great Financial Crisis and the way which it obliged central banks to reinvent themselves occupies an important place. Although this was certainly not the first time in the history of central banking, the magnitude of the modern episode is remarkable. -

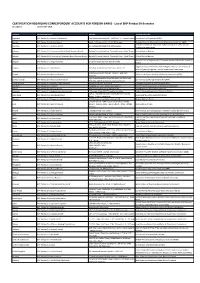

CERTIFICATION REGARDING CORRESPONDENT ACCOUNTS for FOREIGN BANKS - List of BNP Paribas SA Branches Last Update: 11 December 2018

CERTIFICATION REGARDING CORRESPONDENT ACCOUNTS FOR FOREIGN BANKS - List of BNP Paribas SA Branches Last update: 11 December 2018 Country Name of the entity Address Banking authority Argentina BNP Paribas S.A. Buenos Aires Branch Casa Central Bouchard 547, PISOS 26 Y 27 - Capital Federal Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) Austria BNP Paribas S.A. Austria Branch Vordere Zollamtsstraße 13, A-1030 Vienna Austrian Financial Market Authority (Finanzmarktaufsicht - FMA) Australian Prudential Regulation Authority/Australian Securites and Australia BNP Paribas S.A. Australia Branch 60 Castlereagh Street NSW 2000 Sydney Investments commission Bahrain BNP Paribas S.A. Conventional Retail Bank Manama Branch Barhain Financial Harbour, Financial Center - West Tower Central Bank of Bahrain Bahrain BNP Paribas S.A. Conventional Wholesale Bank Manama Branch Barhain Financial Harbour, Financial Center - West Tower Central Bank of Bahrain National Bank of Belgium (NBB)/Financial Services and Market Authority Belgium BNP Paribas S.A. Belgium Branch 3 rue Montagne du Parc, 1000 Bruxelles (FSMA) Bulgarian National Bank/Financial Intelligence Directorate of National Bulgaria BNP Paribas S.A. Sofia Branch 2 Blv Tzar Osvoboditel, 1000 Sofia - PO Box 11 Security Agency/Bulgarian Financial Supervision Commission 1981 Avenue McGill College - Quebec - H3A 2W8 Canada BNP Paribas S.A. Montreal Branch Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OFSI) Montréal Elgin Avenue Picadilly Centre 4th floor, PO BOX 10632 Cayman Islands BNP Paribas S.A. Grand Cayman Branch Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) APO, KY1-1006 Gran Cayman, Cayman Islands Czech Republic BNP Paribas S.A. pobočka Česká Republika Ovocný trh 8 - 117 19 Praha 1 Czech National Bank (Česká národní banka) Denmark BNP Paribas S.A. -

National Bank of Belgium

NATIONAL BANK OF BELGIUM WORKING PAPERS – RESEARCH SERIES ON THE ORIGINS OF THE FRANCO-GERMAN EMU CONTROVERSIES _______________________________ I. Maes(*) The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. As this paper is part of an ongoing research project on economic thought and European integration, I am indebted to many persons for fascinating discussions and suggestions. A special word of thanks goes to J.-P. Abraham, P. Achard, M. Albert, R. Barre, J.-R. Bernard, S. Bertholomé, G. Brouhns, J. de Larosière, A. de Lattre, H. Famerée, L. Gleske, J. Godeaux, G. Grosche, O. Issing, A. Kees, M. Lahnstein, D. Laidler, A. Louw, Ph. Maystadt, J. Michielsen, B. Molitor, F. Mongelli, F.-X. Ortoli, C. Panico, J.-C. Paye, W. Pluym, G. Ravasio, J.-J. Rey, J. Rollo, L. Schubert, J. Smets, G. Tavlas, H. Tietmeyer, J. Vignon, and H. von der Groeben. Earlier drafts have been presented at seminars at the European Central Bank, the Università Frederico II, the Sussex European Institute and conferences of the University Association of Contemporary European Studies and the European Society for the History of Economic Thought. The usual disclaimers apply. (*) NBB, Research Department, University of Leuven and ICHEC (e-mail: [email protected]). NBB WORKING PAPER No.34 - JULY 2002 Editorial Director Jan Smets, Member of the Board of Directors of the National Bank of Belgium Statement of purpose: The purpose of these working papers is to promote the circulation of research results (Research Series) and of analytical studies (Document Series) made within the National Bank of Belgium or presented by outside economists in seminars, conferences and colloquia organised by the Bank. -

The Discount Mechanism in Leading Industrial Countries Since World War Ii

FUNDAMENTAL REAPPRAISAL OF THE DISCOUNT MECHANISM THE DISCOUNT MECHANISM IN LEADING INDUSTRIAL COUNTRIES SINCE WORLD WAR II GEORGE GARVY Prepared for the Steering Committee for the Fundamental Reappraisal of the Discount Mechanism Appointed by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis The following paper is one of a series prepared by the research staffs of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and of the Federal Reserve Banks and by academic economists in connection with the Fundamental Reappraisal of the Discount Mechanism. The analyses and conclusions set forth are those of the author and do not necessarily indicate concurrence by other members of the research staffs, by the Board of Governors, or by the Federal Reserve Banks. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis THE DISCOUNT MECHANISM IN LEADING COUNTRIES SINCE WORLD WAR II George Garvy Federal Reserve Bank of New York Contents Pages Foreword 1 Part I The Discount mechanism as a tool of monetary control. Introduction 2 Provision of central bank credit at the initiative of the banks • . , 4 Discounts 9 Advances . , 12 Widening of the range of objectives and tools of monetary policy 15 General contrasts with the United States 21 Rate policy 33 Quantitative controls 39 Selective controls through the discount window 48 Indirect access to the discount window . 50 Uniformity of administration 53 Concluding remarks 54 Part II The discount mechanism in individual countries. Introduction 58 Austria . f 59 Belgium 71 Canada 85 France 98 Federal Republic of Germany 125 Italy 138 Japan 152 Netherlands l66 Sweden 180 Switzerland 190 United Kingdom 201 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

Statutes of the National Bank of Belgium

STATUTES OF THE NATIONAL BANK OF BELGIUM (Unofficial translation) Latest amendments by the Council of Regency of 14 January 2015, approved by Royal Decree of 10 March 20151. ____________________ CHAPTER I CONSTITUTION Section I - Name, rules applicable and establishments. Article 1. - The National Bank of Belgium, hereinafter referred to as the Bank, in Dutch "Nationale Bank van België", in French "Banque Nationale de Belgique", in German "Belgische Nationalbank", established by the Act of 5 May 1850, shall form an integral part of the European System of Central Banks, hereinafter referred to as ESCB, whose Statute has been established by the Protocol relating to it and annexed to the Treaty establishing the European Community. Furthermore, the Bank shall be governed by the Act of 22 February 1998 establishing the Organic Statute of the National Bank of Belgium, by these Statutes and, additionally, by the provisions relating to public limited liability companies [sociétés anonymes - naamloze vennootschappen]. Pursuant to Article 141 § 1 of the Act of 2 August 2002 on the supervision of the financial sector and on financial services, the words “and, additionally, by the provisions relating to public limited liability companies” are to be interpreted as meaning that the provisions on public limited liability companies do apply to the National Bank of Belgium only : 1° as regards matters which are not governed either by the provisions of Title VII of Part Three of the Treaty establishing the European Community and the Protocol on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank, or by the abovementioned Act of 22 February 1998 or the present Statutes; and 2° in so far as they are not in conflict with the provisions referred to in 1°. -

Working Paper 188 a Century of Macroeconomic and Monetary

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Maes, Ivo Working Paper A century of macroeconomic and monetary thought at the National Bank of Belgium NBB Working Paper, No. 188 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: Maes, Ivo (2010) : A century of macroeconomic and monetary thought at the National Bank of Belgium, NBB Working Paper, No. 188, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/144400 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten -

Payment Systems in Belgium: ELLIPS, the CEC and the Clearing House of Belgium

Payment systems in Belgium Belgium Table of contents List of abbreviations................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1. The institutional aspects................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 General institutional framework........................................................................................... 7 1.2 The role of the central bank ................................................................................................ 9 1.3 The role of other private and public sector bodies ............................................................ 10 2. Payment media used by non-banks............................................................................................ 11 2.1 Cash payments ................................................................................................................. 11 2.2 Non-cash payments .......................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Recent developments ....................................................................................................... 16 3. Interbank exchange and settlement systems.............................................................................. 16 3.1 General overview -

Instruction MARGIN REQUIREMENTS

N° Titre COLLATERAL ACCEPTED TO MEET IV.4-1 Instruction MARGIN REQUIREMENTS Pursuant to Chapter 4 of Title IV of the Clearing Rule Book. PRELIMINARY PROVISIONS Article 1 The provisions of this Instruction do not apply to Special Clearing Members, in the meaning defined in the Clearing Rule Book. Article 2 The provisions of this Instruction apply to the fulfilment of Margins (other than Variation Margin) requirements. The amount of Collateral to be provided corresponds to the Margin requirements which are calculated according to the Clearing Member's Open Positions and the evaluation of the Collateral which has already been provided, (i.e. once the relevant haircuts have been applied). The Margin requirements are sent, on a daily basis, to each Clearing Member by LCH SA. In addition, LCH SA shall send the Intra-day Margin requirements once or several times on each Clearing Day, pursuant to the terms and conditions described in a Notice. Article 3 Further to a trading halt, in application of the circuit breaker rules, Clearing Members may be required to pay additional Initial Margins to LCH SA, on the same day within a reasonable timeframe specified by LCH SA. Article 4 The Collateral posted by a Clearing Member to LCH SA is allocated or registered in the relevant Collateral Account held by LCH SA in the name of that Clearing Member exclusively pursuant to the instruction of the Clearing Member. Any Collateral that remains unallocated after a timeline specified in a Notice will be returned to the Clearing Member. The Collateral posted to cover Client Positions of a Clearing Member shall aim at securing the Open Positions registered in the Clearing Member's Client Position Accounts only.