Leonnatus's Campaign of 322 BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

341 BC the THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes Translated By

1 341 BC THE THIRD PHILIPPIC Demosthenes translated by Thomas Leland, D.D. Notes and Introduction by Thomas Leland, D.D. 2 Demosthenes (383-322 BC) - Athenian statesman and the most famous of Greek orators. He was leader of a patriotic party opposing Philip of Macedon. The Third Philippic (341 BC) - The third in a series of speeches in which Demosthenes attacks Philip of Macedon. Demosthenes urged the Athenians to oppose Philip’s conquests of independent Greek states. Cicero later used the name “Philippic” to label his bitter speeches against Mark Antony; the word has since come to stand for any harsh invective. 3 THE THIRD PHILIPPIC INTRODUCTION To the Third Philippic THE former oration (The Oration on the State of the Chersonesus) has its effect: for, instead of punishing Diopithes, the Athenians supplied him with money, in order to put him in a condition of continuing his expeditions. In the mean time Philip pursued his Thracian conquests, and made himself master of several places, which, though of little importance in themselves, yet opened him a way to the cities of the Propontis, and, above all, to Byzantium, which he had always intended to annex to his dominions. He at first tried the way of negotiation, in order to gain the Byzantines into the number of his allies; but this proving ineffectual, he resolved to proceed in another manner. He had a party in the city at whose head was the orator Python, that engaged to deliver him up one of the gates: but while he was on his march towards the city the conspiracy was discovered, which immediately determined him to take another route. -

Grand Tour of Greece

Grand Tour of Greece Day 1: Monday - Depart USA Depart the USA to Greece. Your flight includes meals, drinks and in-flight entertainment for your journey. Day 2: Tuesday - Arrive in Athens Arrive and transfer to your hotel. Balance of the day at leisure. Day 3: Wednesday - Tour Athens Your morning tour of Athens includes visits to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Panathenian Stadium, the ruins of the Temple of Zeus and the Acropolis. Enjoy the afternoon at leisure in Athens. Day 4: Thursday - Olympia CORINTH Canal (short stop). Drive to EPIDAURUS (visit the archaeological site and the theatre famous for its remarkable acoustics) and then on to NAUPLIA (short stop). Drive to MYCENAE where you visit the archaeological site, then depart for OLYMPIA, through the central Peloponnese area passing the cities of MEGALOPOLIS and TRIPOLIS arrive in OLYMPIA. Dinner & Overnight. Day 5: Friday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of OLYMPIA. Drive via PATRAS to RION, cross the channel to ANTIRION on the "state of the art" new suspended bridge considered to be the longest and most modern in Europe. Arrive in NAFPAKTOS, then continue to DELPHI.. Dinner & Overnight. Day 6: Saturday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of Delphi. Rest of the day at leisure. Dinner & Overnight in DELPHI. Day 6: Sunday – Kalambaka In the morning, start the drive by the central Greece towns of AMPHISSA, LAMIA and TRIKALA to KALAMBAKA. Afternoon visit of the breathtaking METEORA. Dinner & Overnight in KALAMBAKA. Day 7: Monday - Thessaloniki Drive by TRIKALA and LARISSA to the famous, sacred Macedonian town of DION (visit).Then continue to THESSALONIKI, the largest town in Northern Greece. -

TUBERCULOSIS in GREECE an Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country by J

TUBERCULOSIS IN GREECE An Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country By J. B. McDOUGALL, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P. (Ed.), F.R.S.E.; Late Consultant in Tuberculosis, Greece, UNRRA INTRODUCTION In Greece, we follow the traditions of truly great men in all branches of science, and in none more than in the science of medicine. Charles Singer has rightly said - "Without Herophilus, we should have had no Harvey, and the rise of physiology might have been delayed for centuries. Had Galen's works not survived, Vesalius would have never reconstructed anatomy, and surgery too might have stayed behind with her laggard sister, Medicine. The Hippo- cratic collection was the necessary and acknowledged basis for the work of the greatest of modern clinical observers, Sydenham, and the teaching of Hippocrates and his school is still the substantial basis of instruction in the wards of a modern hospital." When we consider the paucity of the raw material with which the Father of Medicine had to work-the absence of the precise scientific method, a population no larger than that of a small town in England, the opposition of religious doctrines and dogma which concerned themselves largely with the healing art, and a natural tendency to speculate on theory rather than to face the practical problems involved-it is indeed remarkable that we have been left a heritage in clinical medicine which has never been excelled. Nearly 2,000 years elapsed before any really vital advances were made on the fundamentals as laid down by the Hippocratic School. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Court of Alexander the Great As Social System

Originalveröffentlichung in Waldemar Heckel/Lawrence Tritle (Hg.), Alexander the Great. A New History, Malden, Mass. u.a. 2009, S. 83-98 5 The Court of Alexander the Great as Social System Gregor Weber In his discussion of events that followed Alexander ’s march through Hyrcania (summer 330), Plutarch gives a succinct summary of the king ’s conduct and reports the clash of his closest friends, Hephaestion and Craterus (Alex. 47.5.9-11).1 The passage belongs in the context of Alexander ’s adoption of the traditions and trap pings of the dead Persian Great King (Fredricksmeyer 2000; Brosius 2003a), although the conflict between the two generals dates to the time of the Indian campaign (probably 326). It reveals not only that Alexander was subtly in tune with the atti tudes of his closest friends, but also that his changes elicited varied responses from the members of his circle. Their relationships with each other were based on rivalry, something Alexander - as Plutarch ’s wording suggests - actively encouraged. But it is also reported that Alexander made an effort to bring about a lasting reconcili ation of the two friends, who had attacked each other with swords, and drawn their respective troops into the fray. To do so, he had to marshal “all his resources ” (Hamilton 1969; 128-31) from gestures of affection to death threats. These circumstances invite the question: what was the structural relevance of such an episode beyond the mutual antagonism of Hephaestion and Craterus? For these were not minor protagonists, but rather men of the upper echelon of the new Macedonian-Persian empire, with whose help Alexander had advanced his con quest ever further and exercised his power (Berve nos. -

Name Address Postal City Mfi Id Head Office Res* Greece

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* GREECE Central Banks GR010 Bank of Greece, S.A. 21, Panepistimiou Str. 102 50 Athens No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GR060 ABN Amro Bank 348, Syngrou Avenue 176 74 Athens NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. Yes GR077 Achaiki Co-operative Bank, L.L.C. 66, Michalakopoulou Str. 262 21 Patra Yes GR056 Aegean Baltic Bank S.A. 28, Diligianni Str. 145 62 Athens Yes GR014 Alpha Bank, S.A. 40, Stadiou Str. 102 52 Athens Yes GR100 American Bank of Albania Greek Branch 14, E. Benaki Str. 106 78 Athens AL American Bank of Albania Yes GR080 American Express Bank 280, Kifissias Avenue 152 32 Athens US American Express Yes Company GR047 Aspis Bank S.A. 4, Othonos Str. 105 57 Athens Yes GR043 ATE Bank, S.A. 23, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens Yes GR016 Attica Bank, S.A. 23, Omirou Str. 106 72 Athens Yes GR081 Bank of America N.A. 35, Panepistimiou Str. 102 27 Athens US Bank of America Yes Corporation GR073 Bank of Cyprus Limited 170, Alexandras Avenue 115 21 Athens CY Bank of Cyprus Public Yes Company Ltd GR050 Bank Saderat Iran 25, Panepistimiou Str. 105 64 Athens IR Bank Saderat Iran Yes GR072 Bayerische Hypo und Vereinsbank A.G. 7, Irakleitou Str. 106 73 Athens DE Bayerische Hypo- und Yes Vereinsbank AG GR105 BMW Austria Bank GmbH Zeppou 33 166 57 Athens AT BMW Austria Bank GmbH Yes GR070 BNP Paribas 94, Vas. Sofias Avenue 115 28 Athens FR Bnp paribas Yes GR039 BNP Paribas Securities Services 94, Vas. -

Public Finance and Democratic Ideology in Fourth-Century BC Athens by Christopher Scott Welser BA, Sw

Dēmos and Dioikēsis: Public Finance and Democratic Ideology in Fourth-Century B.C. Athens By Christopher Scott Welser B.A., Swarthmore College, 1994 M.A., University of Maryland, 1999 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. May, 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Christopher Scott Welser This dissertation by Christopher Scott Welser is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date________________ _______________________________________ Adele C. Scafuro, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date________________ _______________________________________ Alan L. Boegehold, Reader Date________________ _______________________________________ David Konstan, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date________________ _______________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Christopher Scott Welser was born in Romeo, Michigan in 1971. He attended Roeper City and Country School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and in 1994 he graduated from Swarthmore College, earning an Honors B.A. in Economics (his major) and Biology (his minor). After working for several years at public policy research firms in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, he decided to pursue the study of Classics, an interest of his since childhood. Upon earning an M.A. with Distinction in Latin and Greek from the University of Maryland at College Park in 1999, he enrolled in the Ph.D. program in Classics at Brown University. While working on his Ph.D., he spent two years as Seymour Fellow (2002-2003) and Capps Fellow (2004-2005) at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and participated in the summer program of the American Academy in Rome (2000). -

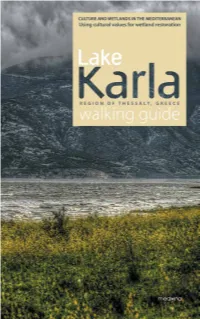

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

(Pelasgians/Pelasgi/Pelasti/Pelišti) – the Archaic Mythical Pelasgo/Stork-People from Macedonia

Basil Chulev • ∘ ⊕ ∘ • Pelasgi/Balasgi, Belasgians (Pelasgians/Pelasgi/Pelasti/Pelišti) – the Archaic Mythical Pelasgo/Stork-people from Macedonia 2013 Contents: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Macedonians from Pella and Pelasgians from Macedon – origin of the Pelasgians ....... 16 Religion of the Pelasgians …………………..…………………………………..……… 32 Pelasgian language and script .......................................................................................... 39 Archaeological, Etymological, Mythological, and Genetic evidence of Pelasgic origin of Macedonians .................................................................................................................... 52 References ........................................................................................................................ 64 Introduction All the Macedonians are familiar with the ancient folktale of 'Silyan the Stork' (Mkd.latin: Silyan Štrkot, Cyrillic: Сиљан Штркот). It is one of the longest (25 pages) and unique Macedonian folktales. It was recorded in the 19th century, in vicinity of Prilep, Central Macedonia, a territory inhabited by the most direct Macedonian descendents of the ancient Bryges and Paionians. The notion of Bryges appear as from Erodot (Lat. Herodotus), who noted that the Bryges lived originally in Macedonia, and when they moved to Asia Minor they were called 'Phryges' (i.e. Phrygians). Who was Silyan? The story goes: Silyan was banished -

Print This Article

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 58, 2021 The March 2021 Thessaly earthquakes and their impact through the prism of a multi-hazard approach in disaster management Mavroulis Spyridon Department of Dynamic Tectonic Applied Geology, Faculty of Geology and Geoenvironment, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens Mavrouli Maria Department of Microbiology, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens Carydis Panayotis European Academy of Sciences and Arts Agorastos Konstantinos Region of Thessaly, Larissa Lekkas Efthymis Department of Dynamic Tectonic Applied Geology, Faculty of Geology and Geoenvironment, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.26852 Copyright © 2021 Spyridon Mavroulis, Maria Mavrouli, Panayotis Carydis, Konstantinos Agorastos, Efthymis Lekkas To cite this article: Mavroulis, S., Mavrouli, M., Carydis, P., Agorastos, K., & Lekkas, E. (2021). The March 2021 Thessaly earthquakes and their impact through the prism of a multi-hazard approach in disaster management. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 58, 1-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.26852 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 05/10/2021 09:49:56 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 05/10/2021 09:49:56 | Volume 58 BGSG Research Paper THE MARCH 2021 THESSALY EARTHQUAKES AND THEIR IMPACT Correspondence to: THROUGH THE PRISM OF A MULTI-HAZARD APPROACH IN DISASTER Spyridon Mavroulis MANAGEMENT [email protected]