Modern and Folk Sports in Central Asia Under Lenin and Stalin: Uzbekistan from 1925 to 1952

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

U.S. Citizenship Non-Precedent Decision of the and Immigration Administrative Appeals Office Services In Re: 8865906 Date: NOV. 30, 2020 Appeal of Nebraska Service Center Decision Form 1-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Extraordinary Ability) The Petitioner, a martial arts athlete and coach, seeks classification as an alien of extraordinary ability. See Immigration and Nationality Act (the Act) section 203(b)(l)(A), 8 U.S.C. § l 153(b)(l)(A). This first preference classification makes immigrant visas available to those who can demonstrate their extraordinary ability through sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in their field through extensive documentation. The Director of the Nebraska Service Center denied the petition, concluding that the record did not establish that the Petitioner met the initial evidence requirements through receipt of a major, internationally recognized award or meeting three of the evidentiary criteria at 8 C.F.R. § 204.5(h)(3). In these proceedings, it is the Petitioner's burden to establish eligibility for the requested benefit. See Section 291 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1361. Upon de nova review, we will dismiss the appeal. I. LAW Section 203(b)(l) of the Act makes visas available to immigrants with extraordinary ability if: (i) the alien has extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics which has been demonstrated by sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in the field through extensive documentation, (ii) the alien seeks to enter the United States to continue work in the area of extraordinary ability, and (iii) the alien's entry into the United States will substantially benefit prospectively the United States. -

ISF 2019 Season World of School Sport

MAGAZINE Launch of the ISF 2019 Season World of School Sport p.6 She Runs - Active Girls’ Lead Project p.9 Inside ISF p.20 ISF & Youth She Runs project through the eyes of youth p.24 Interview ISF EC Member Mr Panya Hanlumyuang p.26 FEB - MAR #20 WE ARE SCHOOL SPORT 2019 2 | ISF IN MOTION ISF IN MOTION | 3 ISF Magazine | FEBRUARY - MARCH 2019 FEBRUARY - MARCH 2019 | ISF Magazine 4 | SUMMARY RENDEZ-VOUS WITH THE PRESIDENT | 5 SUMMARY "Rendez-Vous" WITH THE PRESIDENT #20 | January - March | 2019 As we begin yet another busy and eventful year, let us take a moment to reflect 2 | ISF in Motion and appreciate the success we have achieved in 2018. Follow us on 5 | I am delighted with the strides we have taken this past year and cannot thank you all enough "Rendez-Vous" with the President for the passion and dedication displayed in helping the ISF develop and grow. Nonetheless, I am happy to say that for 2019 we are not content with just sitting back and admiring our past 6 | World of school sport successes, with the new year bringing about a very important transitional period. 7 | With the close of 2018, our Executive Committee meeting hosted in Sochi, Russian Federation was able to decide upon the progression of the ISF secretariat and Committee. This outcome 8 | Food for thought was greatly needed and will help in strengthening and broadening the ISF’s ability to develop school sport and expand our reach. This will be partly thanks to the new structure involving to a higher degree, member countries, helping expand and improve our ability to provide youth 9 | She Runs - Active Girls’ Lead Project with professionally run sport events. -

Qatar's Sports Strategy: a Case of Sports Diplomacy Or Sportswashing?

Qatar’s sports strategy: A case of sports diplomacy or sportswashing? Håvard Stamnes Søyland Master in, International Studies Supervisor: PhD Marcelo Adrian Moriconi Bezerra, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon Co-Supervisor: PhD Cátia Miriam da Silva Costa, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon November, 2020 Qatar’s sports strategy: A case of sports diplomacy or sportswashing? Håvard Stamnes Søyland Master in, International Studies Supervisor: PhD Marcelo Adrian Moriconi Bezerra, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon Co-Supervisor: PhD Cátia Miriam da Silva Costa, Researcher and Invited Assistant Professor Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon November, 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Marcelo Moriconi for his help with this dissertation and thank ISCTE for an interesting master program in International Studies. I would like to thank all the interesting people I have met during my time in Lisbon, which was an incredible experience. Last but not least I would like to thank my family and my friends at home. Thank you Håvard Stamnes Søyland Resumo Em Dezembro de 2010, o Qatar conquistou os direitos para o Campeonato do Mundo FIFA 2020. Nos anos seguintes, o Qatar ganhou uma influência significativa no desporto global. Este pequeno estado desértico tem sido o anfitrião de vários eventos desportivos internacionais durante a última década e aumentou a sua presença global através do investimento em desportos internacionais, do patrocínio de negócios desportivos, da aquisição de clubes de futebol, da aquisição de direitos de transmissão desportiva e da criação de instalações desportivas de última geração. -

Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants

IAAF World Championships • Biographical Entry List (may include reserves) Womenʼs 100 Metres 51 Entrants Starts Sunday, August 11 Age (Days) Born 2013 Best Personal Best 112 BREEN Melissa AUS 22y 326d 1990 11.25 -13 11.25 -13 Won sprint double at 2012 Australian Championships ... 200 pb: 23.12 -13. sf WJC 100 2008; 1 Pacific Schools Games 100 2008; 8 WSG 100 2009; 8 IAAF Continental Cup 100 2010; sf COM 100 2010; ht OLY 100 2012. 1 Australian 100/200 2012 (1 100 2010). Coach-Matt Beckenham In 2013: 1 Canberra 100/200; 1 Adelaide 100/200; 1 Sydney “Classic” 100/200; 3 Hiroshima 100; 3 Fukuroi 200; 7 Tokyo 100; 3ht Nivelles 100; 2 Oordegem Buyle 100 (3 200); 6 Naimette-Xhovémont 100; 6 Lucerne 100 ʻBʼ; 2 Belgian 100; 3 Ninove Rasschaert 200 129 ARMBRISTER Cache BAH 23y 317d 1989 11.35 11.35 -13 400 pb: 53.45 -11 (55.28 -13). 200 pb: 23.13 -08 (23.50 -13). 3 Central American & Caribbean Champs 4x100 2011. Student of Marketing at Auburn University In 2013: 1 Nassau 400 ʻBʼ; 6 Cayman Islands Invitational 200; 4 Kingston ”Jamaica All-Comers” 100; 1 Kingston 100 ʻBʼ (May 25); 1 Kingston 200 (4 100) (Jun 8); 2 Bahamian 100; 5 Central American & Caribbean Champs 100 (3 4x100) 137 FERGUSON Sheniqua BAH 23y 258d 1989 11.18 11.07 -12 2008 World Junior Champion at 200m ... led off Bahamas silver-winning sprint relay team at the 2009 World Championships 200 pb: 22.64 -12 (23.32 -13). sf World Youth 100 2005 (ht 200); 2 Central American & Caribbean junior 100 2006; 1 WJC 200 2008 (2006-8); qf OLY 200 2008; 2 WCH 4x100 2009 (sf 200, qf 100); sf WCH 200 2011; sf OLY 100 2012. -

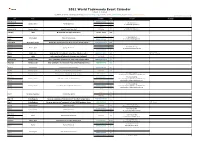

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar

2021 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (subject to change) ※ Grade of event is distinguished by colour: Blue-Kyorugi, Red-Poomsae, Green-Para, Purple-Junior, Orange-Team, (as of 15th January, 2021) Date Place Event Discipline Grade Contacts Remarks February 20-21 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Open 2021 February 22 CADET N/A (E ) [email protected] February 23 JUNIOR N/A (T) 0090 530 575 27 00 February 25-26 Istanbul, Turkey Turkish Poomsae Open 2021 POOMSAE G-1 (E ) [email protected] February Online World Taekwondo Super Talent Show TALENT SHOW N/A - March 6 CADET & JUNIOR N/A (T) 359 8886 84548 Sofia, Bulgaria Ramus Sofia Open 2021 March 7 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (E ) [email protected] March 8-10 Riyad, Saudi Arabia Riyadh 2021 World Taekwondo Women's Open Championships SENIOR KYORUGI TBD March 12 CADET N/A (T) 34 965 37 00 63 March 13 Alicante, Spain Spanish Open 2021 JUNIOR N/A (E ) [email protected] March 14 SENIOR KYORUGI G-1 (PSS : Daedo) March Wuxi, China Wuxi 2020 World Taekwondo Grand Slam Champions Series SENIOR KYORUGI N/A Postponed to 2021 March Online Online 2021 World Taekwondo Poomsae Open Challenge I POOMSAE G-4 March 26-27 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games SENIOR KYORUGI N/A March 28 Amman, Jordan Asian Qualification Tournament for Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games PARA KYORUGI G-1 April 8-11 Sofia, Bulgaria European Senior Championships SENIOR KYORUGI G-2 April 19 Beirut, Lebanon 6th Asian Taekwondo Poomsae Championships POOMSAE G-4 -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

NAVIGATING THE ‘DRUNKEN REPUBLIC’: THE JUNO AND THE RUSSIAN AMERICAN FRONTIER, 1799-1811 By TOBIN JEREL SHOREY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Tobin Jerel Shorey To my family, friends, and faculty mentors ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my parents and family, whose love and dedication to my education made this possible. I would also like to thank my wife, Christy, for the support and encouragement she has given me. In addition, I would like to extend my appreciation to my friends, who provided editorial comments and inspiration. To my colleagues Rachel Rothstein and Lisa Booth, thank you for all the lunches, discussions, and commiseration. This work would not have been possible without the support of all of the faculty members I have had the pleasure to work with over the years. I also appreciate the efforts of my PhD committee members in making this dream a reality: Stuart Finkel, Alice Freifeld, Peter Bergmann, Matthew Jacobs, and James Goodwin. Finally, I would like to thank the University of Florida for the opportunities I have been afforded to complete my education. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

2001 Report Olympic Solidarity

2001 - 2004 Quadrennial plan 2001 Report Olympic Solidarity Contents 1 Message by the Olympic Solidarity Director 2 A vast programme making everyone a winner 3 A big cheer for all our partners! 5 Changes to the Olympic Solidarity Commission 6 Structures adapted for decentralisation 7 Programmes and budgets 8 Widespread, targeted communication 10 World programmes 14 Athletes 16 Salt Lake City 2002 – NOC preparation programme 18 Olympic Scholarships for athletes “Athens 2004” 22 Athens 2004 – Team sports support grants 26 Regional and Continental Games – NOC preparation programme 28 Youth Development Programme 30 Coaches 34 Technical courses 36 Scholarships for coaches 38 Development of national coaching structure 42 NOC Management 46 NOC infrastructure 48 Sports administrators programme 50 High-level education for sports administrators 52 NOC management consultancy 54 Regional forums 56 Special Fields 60 Olympic Games participation 62 Sports Medicine 64 Sport and the Environment 66 Women and Sport 68 International Olympic Academy 70 Sport for All 72 Culture and Education 74 NOC Legacy 76 Continental programmes 80 Continental Associations take stock 82 Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa (ANOCA) 82 Pan American Sports Organisation (PASO) 84 Olympic Council of Asia (OCA) 86 The European Olympic Committees (EOC) 88 Oceania National Olympic Committees (ONOC) 90 Abbreviations 93 2 3 For Olympic Solidarity, 2001 was the first year of the new quadrennial period 2001- 2004. The main focus of these four years can be summed up in one word: decen- tralisation. The pace of the decentralisation process, which began slowly during the previous plan, has been gradually stepped up, with full co-operation between the different organisations involved and in the knowledge that the continental bodies responsible for decentralised management are suitably equipped for the task. -

AGENDA 63Rd ABU SPORTS GROUP CONFERENCE & ASSOCIATED

AGENDA 63rd ABU SPORTS GROUP CONFERENCE & ASSOCIATED MEETINGS Sept 30 – Oct 1, 2018 Venue: Banquet Room 2, Hotel YYLDYZ, Ashgabat, Turkmenistan DAY 1 : SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 08:00 - 09:00 REGISTRATION 09:00 - 10:30 Broadcast Rights Committee Meeting 10:30 - 11:00 Coffee Break 11:00 - 12:30 Finance Committee Meeting OPENING CEREMONY 14:00 - 14:10 Opening Remarks by Mr Jiang Heping, Chairperson ABU Sports Group 14:10 - 14:20 Welcome Remarks by Vice Chairman, News and Sports TVTM (TBC) Keynote Address by His Excellency, Mr. Dayanch Gulgeldiyev, Minister of Sport & Youth Policy of 14:20 - 14:30 Turkmenistan 14:30 - 14:40 Opening Remarks by Dr Javad Mottaghi, the Secretary-General ABU 14:40 - 15:00 Group Photo 15:00 - 15:30 Report by Mr Cai Yanjiang, Director of ABU Sports followed by Q&A 15:30 - 16:00 Coffee Break Members Forum Followed by Q&A & Discussion This session provides a glimpses of the sports broadcasting in different countries and the region. Selected 16:00 members share experiences, challenges and opportunities among others. Areas of focus include broadcast rights to production and transmission and technological developments. Sports Broadcasting in Turkmenistan by Host TVTM The first Presentation of the 63rd Sports Group Conference and Associated Meetings is from our host TVTM, Turkmenistan. The Secretary General of the Olympic Committee of Turkmenistan Mr Azat Myradov and the 16:00 - 16:15 Chief of Sport TV Channel of Turkmenistan Mr Resul Babayev will talk about “Weightlifting World Championship 2018 in Ashgabat. They will also share development of Sports and the new trends in Turkmenistan. -

Chapter I Problems of Working out the E – Text Book for Teaching

C o n t e n t s Introduction…………………………………………………………… Chapter I Problems of working out the E – text book for teaching “Practical English”.………………………………………………….. 1:1A brief information about the history of compiling E – textbooks …………………………………………………………… 1:2 Importance of E – books in the modern of technology Education ……………………………………………………………. 1:3 The aims and the Parts of the E –textbook on practical English for Intermediate and Advanced level students………………… Conclusion……………………………………………………………… Chapter II Structure of the E – book on the topic “Sport in Uzbekistan”.…………………… Information resources……………………………………………. Introduction The present qualification paper deals with the study of the Structure of the E – book on the topic “Sport in Uzbekistan” which presents a certain interest both the theoretical investigation and for the practical language use. The president of the republic of Uzbekistan. Islam Abduganievich Karimov speaking about the future of Uzbekistan underlines that “Harmonious generation is the future guarantee of prosperity”. It is our task to prepare and teach professionally competent and energetic personnel, real patriots to see them in the world depository of science and culture. In this plan the national program about training personal was worked out on the formation of new generation of specialist. “With the high common and professionally culture, creative and social activity, with the ability to orientate in the social and political life independently, capable to raise and solve the problems to the perspective”. Here the notable place is assigned to the general applied linguistics which carries responsibility for such socially and scientifically important sphere of knowledge as lexicography text logy dictionary methods of language training, translation theory and so on. -

Our Outstanding Graduates

OUR OUTSTANDING GRADUATES Aimagambetov Erkara Balkaraevich Rector of Karaganda economic university, d.e.sc., professor Doctor of Economics, Professor, Corresponding Member IHEAS, academician of the IEA Eurasia In 1970 Aimagambetov E.B. graduated with distinction from the Karaganda Cooperative Institute of Centrosoyuz. In 1989 he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation on the specialty "Political Economy" at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kiev. From 1991 to 1997 held a position of Vice Rector for Academic Affairs of the Karaganda Cooperative Institute of Centrosoyuz. Since 1997 he has been the Rector of Karaganda Economic University of Kazpotrebsoyuz. Aimagambetov E.B is a Chairman of Karaganda regional territorial election commission, Chairman of the Public Council for Combating Corruption under the NDP "Nur Otan", a member of the Disciplinary Board of the Agency for Civil Service in the Karaganda region. He was awarded the medal "For valorous work" to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Lenin, the medal "For Labor Valor", "Kurmet" (2004), Jubilee Medal "Kazakhstan Constitution 10 zhyl " (2005), silver medal "A.Baytursynov" (2006), a medal for the 10th anniversary of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2007), jubilee Medal "10 zhyl Astana" (2007), the Order "Parasat" (2009). Ashlyaev Hazbolat Sopyzhanovich Chairman of the Kazpotrebsoyuz Graduated Karaganda Cooperative Institute (1970.), economist. After graduation he worked as a mezhraybaza commodity, instructor, chief of organizational -

Sport As an Important Factor of Strengthening Tolerance (The Case of Kazakhstan)

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 38 (Nº 46) Year 2017. Page 40 Sport as an important factor of strengthening tolerance (The case of Kazakhstan) El deporte como factor importante de fortalecimiento de la tolerancia (El caso de Kazajstán) B. DOSKARAYEV 1; A. KULBAYEV 2 Received: 22/09/2017 • Approved: 25/09/2017 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Methodology 3. Results of the study and their discussion 4. Conclusion References ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: The article highlights the importance of the sport, El artículo destaca la importancia del deporte, el Olympic movement, Olympic Games, international movimiento olímpico, los Juegos Olímpicos, los eventos sporting events as the main factor in strengthening deportivos internacionales como el factor principal en el interethnic friendship, tolerance and friendship. Based fortalecimiento de la amistad interétnica, la tolerancia y on the statements and conclusions of famous la amistad. Basándose en las declaraciones y personalities of the sphere of sports movement, the conclusiones de personalidades famosas de la esfera del authors give analyzes and opinions. Especially, movimiento deportivo, los autores dan análisis y information is provided on the role of international opiniones. Sobre todo, se proporciona información sports relations in the formation of a worldwide sobre el papel de las relaciones deportivas understanding among the peoples of the world and internacionales en la formación de un entendimiento significant international events in this area. mundial entre los pueblos del mundo y los importantes Key words: Tolerance, sport, peace, Olympic acontecimientos internacionales en este ámbito. movement, international sporting events, international Palabras clave: tolerancia, deporte, paz, movimiento sporting relations. -

Technologies of Power, Governmentality and Olympic Discourses: Using Fouca

Esporte e Sociedade ano 4, n 12, Jul.2009/Out.2009 Technologies of Power Chatziefstathiou/Henry TECHNOLOGIES OF POWER, GOVERNMENTALITY AND OLYMPIC DISCOURSES: A FOUCAULDIAN ANALYSIS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE DISCURSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE OLYMPIC IDEOLOGY Dikaia Chatziefstathiou Department of Sport Science, Tourism and Leisure Canterbury Christ Church University - UK Ian Henry Centre for Olympic Studies & Research Loughborough University - UK Abstract This article discusses the process of construction of Olympic discourses during the early years of the modern Olympic Movement. It focuses on documents written by the founder of the Olympic Movement, Baron Pierre de Coubertin and adopts a Foucauldian analysis for understanding the discursive construction of the Olympic discourses. Thus our approach is more concerned with the constitution of knowledges and discourses rather than with the historical approach focusing on personalities, structures and context. Core to our discussion will be the Foucauldian bio-politics and neo-liberal governmentality which refer to socio-political contexts where power is decentred and members of society play an active role in their own self-regulation and self-government. The article will consider the use of the body as a regulatory force for the discursive constructions of classist and gendered discourses of the Olympic ideology. Keywords: Olympism, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, Governmentality, Discourse Analysis, Foucauldian analysis Introduction In this paper we seek to understand the process of construction of