Slide 2 a Superscalar Implementation of the Processor Architecture Is One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

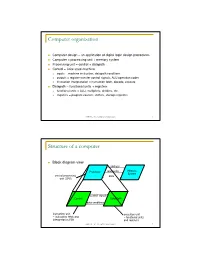

Computer Organization

Computer organization Computer design – an application of digital logic design procedures Computer = processing unit + memory system Processing unit = control + datapath Control = finite state machine inputs = machine instruction, datapath conditions outputs = register transfer control signals, ALU operation codes instruction interpretation = instruction fetch, decode, execute Datapath = functional units + registers functional units = ALU, multipliers, dividers, etc. registers = program counter, shifters, storage registers CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 1 Structure of a computer Block diagram view address Processor read/write Memory System central processing data unit (CPU) control signals Control Data Path data conditions instruction unit execution unit œ instruction fetch and œ functional units interpretation FSM and registers CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 2 Registers Selectively loaded – EN or LD input Output enable – OE input Multiple registers – group 4 or 8 in parallel LD OE D7 Q7 OE asserted causes FF state to be D6 Q6 connected to output pins; otherwise they D5 Q5 are left unconnected (high impedance) D4 Q4 D3 Q3 D2 Q2 LD asserted during a lo-to-hi clock D1 Q1 transition loads new data into FFs D0 CLK Q0 CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 3 Register transfer Point-to-point connection MUX MUX MUX MUX dedicated wires muxes on inputs of each register rs rt rd R4 Common input from multiplexer load enables rs rt rd R4 for each register control signals MUX for multiplexer Common bus with output enables output enables and load rs rt rd R4 enables for each register BUS CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 4 Register files Collections of registers in one package two-dimensional array of FFs address used as index to a particular word can have separate read and write addresses so can do both at same time 4 by 4 register file 16 D-FFs organized as four words of four bits each write-enable (load) 3E RB read-enable (output enable) RA WE (- WB (. -

Balanced Multithreading: Increasing Throughput Via a Low Cost Multithreading Hierarchy

Balanced Multithreading: Increasing Throughput via a Low Cost Multithreading Hierarchy Eric Tune Rakesh Kumar Dean M. Tullsen Brad Calder Computer Science and Engineering Department University of California at San Diego {etune,rakumar,tullsen,calder}@cs.ucsd.edu Abstract ibility of SMT comes at a cost. The register file and rename tables must be enlarged to accommodate the architectural reg- A simultaneous multithreading (SMT) processor can issue isters of the additional threads. This in turn can increase the instructions from several threads every cycle, allowing it to clock cycle time and/or the depth of the pipeline. effectively hide various instruction latencies; this effect in- Coarse-grained multithreading (CGMT) [1, 21, 26] is a creases with the number of simultaneous contexts supported. more restrictive model where the processor can only execute However, each added context on an SMT processor incurs a instructions from one thread at a time, but where it can switch cost in complexity, which may lead to an increase in pipeline to a new thread after a short delay. This makes CGMT suited length or a decrease in the maximum clock rate. This pa- for hiding longer delays. Soon, general-purpose micropro- per presents new designs for multithreaded processors which cessors will be experiencing delays to main memory of 500 combine a conservative SMT implementation with a coarse- or more cycles. This means that a context switch in response grained multithreading capability. By presenting more virtual to a memory access can take tens of cycles and still provide contexts to the operating system and user than are supported a considerable performance benefit. -

Data-Flow Prescheduling for Large Instruction Windows in Out-Of-Order Processors

Data-Flow Prescheduling for Large Instruction Windows in Out-of-Order Processors Pierre Michaud, Andr´e Seznec IRISA/INRIA Campus de Beaulieu, 35042 Rennes Cedex, France {pmichaud, seznec}@irisa.fr Abstract We introduce data-flow prescheduling. Instructions are sent to the issue buffer in a predicted data-flow order instead The performance of out-of-order processors increases of the sequential order, allowing a smaller issue buffer. The with the instruction window size. In conventional proces- rationale of this proposal is to avoid using entries in the is- sors, the effective instruction window cannot be larger than sue buffer for instructions which operands are known to be the issue buffer. Determining which instructions from the yet unavailable. issue buffer can be launched to the execution units is a time- In our proposal, this reordering of instructions is accom- critical operation which complexity increases with the issue plished through an array of schedule lines. Each schedule buffer size. We propose to relieve the issue stage by reorder- line corresponds to a different depth in the data-flow graph. ing instructions before they enter the issue buffer. This study The depth of each instruction in the data-flow graph is de- introduces the general principle of data-flow prescheduling. termined, and the instruction is inserted in the correspond- Then we describe a possible implementation. Our prelim- ing schedule line. Lines are consumed by the issue buffer inary results show that data-flow prescheduling makes it sequentially. possible to enlarge the effective instruction window while Section 2 briefly describes issue buffers and discusses re- keeping the issue buffer small. -

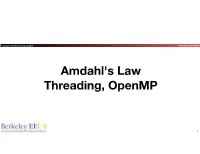

Amdahl's Law Threading, Openmp

Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver Amdahl's Law Threading, OpenMP 1 Big Idea: Amdahl’s (Heartbreaking) Law Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • Speedup due to enhancement E is Exec time w/o E Speedup w/ E = ---------------------- Exec time w/ E • Suppose that enhancement E accelerates a fraction F (F <1) of the task by a factor S (S>1) and the remainder of the task is unaffected Execution Time w/ E = Execution Time w/o E × [ (1-F) + F/S] Speedup w/ E = 1 / [ (1-F) + F/S ] 2 Big Idea: Amdahl’s Law Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver Speedup = 1 (1 - F) + F Non-speed-up part S Speed-up part Example: the execution time of half of the program can be accelerated by a factor of 2. What is the program speed-up overall? 1 1 = = 1.33 0.5 + 0.5 0.5 + 0.25 2 3 Example #1: Amdahl’s Law Speedup w/ E = 1 / [ (1-F) + F/S ] Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • Consider an enhancement which runs 20 times faster but which is only usable 25% of the time Speedup w/ E = 1/(.75 + .25/20) = 1.31 • What if its usable only 15% of the time? Speedup w/ E = 1/(.85 + .15/20) = 1.17 • Amdahl’s Law tells us that to achieve linear speedup with 100 processors, none of the original computation can be scalar! • To get a speedup of 90 from 100 processors, the percentage of the original program that could be scalar would have to be 0.1% or less Speedup w/ E = 1/(.001 + .999/100) = 90.99 4 Amdahl’s Law If the portion of Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 the program that Wawrzynek and Weaver can be parallelized is small, then the speedup is limited The non-parallel portion limits the performance 5 Strong and Weak Scaling Computer Science 61C Spring 2018 Wawrzynek and Weaver • To get good speedup on a parallel processor while keeping the problem size fixed is harder than getting good speedup by increasing the size of the problem. -

GPU Implementation Over IPTV Software Defined Networking

Esmeralda Hysenbelliu. Int. Journal of Engineering Research and Application www.ijera.com ISSN : 2248-9622, Vol. 7, Issue 8, ( Part -1) August 2017, pp.41-45 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS GPU Implementation over IPTV Software Defined Networking Esmeralda Hysenbelliu* Information Technology Faculty, Polytechnic University of Tirana, Sheshi “Nënë Tereza”, Nr.4, Tirana, Albania Corresponding author: Esmeralda Hysenbelliu ABSTRACT One of the most important issue in IPTV Software defined Network is Bandwidth Issue and Quality of Service at the client side. Decidedly, it is required high level quality of images in low bandwidth and for this reason it is needed different transcoding standards (Compression of image as much as it is possible without destroying the quality of it) as H.264, H265, VP8 and VP9. During a test performed in SMC IPTV SDN Cloud Network, it was observed that with a server HP ProLiant DL380 g6 with two physical processors there was not possible to transcode in format H.264 more than 30 channels simultaneously because CPU’s achieved 100%. This is the reason why it was immediately needed to use Graphic Processing Units called GPU’s which offer high level images processing. After GPU superscalar processor was integrated and done functional via module NVENC of FFEMPEG Program, number of channels transcoded simultaneously was tremendous increased (more than 100 channels). The aim of this paper is to real implement GPU superscalar processors in IPTV Cloud Networks by achieving improvement of performance to more than 60%. Keywords - GPU superscalar processor, Performance Improvement, NVENC, CUDA --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 01 -05-2017 Date of acceptance: 19-08-2017 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. -

Review of Computer Architecture

Basic Computer Architecture CSCE 496/896: Embedded Systems Witawas Srisa-an Review of Computer Architecture Credit: Most of the slides are made by Prof. Wayne Wolf who is the author of the textbook. I made some modifications to the note for clarity. Assume some background information from CSCE 430 or equivalent von Neumann architecture Memory holds data and instructions. Central processing unit (CPU) fetches instructions from memory. Separate CPU and memory distinguishes programmable computer. CPU registers help out: program counter (PC), instruction register (IR), general- purpose registers, etc. von Neumann Architecture Memory Unit Input CPU Output Unit Control + ALU Unit CPU + memory address 200PC memory data CPU 200 ADD r5,r1,r3 ADD IRr5,r1,r3 Recalling Pipelining Recalling Pipelining What is a potential Problem with von Neumann Architecture? Harvard architecture address data memory data PC CPU address program memory data von Neumann vs. Harvard Harvard can’t use self-modifying code. Harvard allows two simultaneous memory fetches. Most DSPs (e.g Blackfin from ADI) use Harvard architecture for streaming data: greater memory bandwidth. different memory bit depths between instruction and data. more predictable bandwidth. Today’s Processors Harvard or von Neumann? RISC vs. CISC Complex instruction set computer (CISC): many addressing modes; many operations. Reduced instruction set computer (RISC): load/store; pipelinable instructions. Instruction set characteristics Fixed vs. variable length. Addressing modes. Number of operands. Types of operands. Tensilica Xtensa RISC based variable length But not CISC Programming model Programming model: registers visible to the programmer. Some registers are not visible (IR). Multiple implementations Successful architectures have several implementations: varying clock speeds; different bus widths; different cache sizes, associativities, configurations; local memory, etc. -

Jetson TX2 • NVIDIA Jetson Xavier • GPU Programming • Algorithm Mapping: • Convolutions Parallel Algorithm Execution

GPU and multicore CPU architectures. Algorithm mapping Contributors: N. Tsapanos, I. Karakostas, I. Pitas Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Presenter: Prof. Ioannis Pitas Aristotle University of Thessaloniki [email protected] www.multidrone.eu Presentation version 1.3 GPU and multicore CPU architectures. Algorithm mapping • GPU and multicore CPU processing boards • Graphics cards • NVIDIA Jetson TX2 • NVIDIA Jetson Xavier • GPU programming • Algorithm mapping: • Convolutions Parallel algorithm execution • Graphics computing: • Highly parallelizable • Linear algebra parallelization: • Vector inner products: 푐 = 풙푇풚. • Matrix-vector multiplications 풚 = 푨풙. • Matrix multiplications: 푪 = 푨푩. Parallel algorithm execution • Convolution: 풚 = 푨풙 • CNN architectures, linear systems, signal filtering. • Correlation: 풚 = 푨풙 • template matching, tracking. • Signal transforms (DFT, DCT, Haar, etc): • Matrix vector product form: 푿 = 푾풙 • 2D transforms (matrix product form): 푿’ = 푾푿. Processing Units • Multicore (CPU): • MIMD. • Focused on latency. • Best single thread performance. • Manycore (GPU): • SIMD. • Focused on throughput. • Best for embarrassingly parallel tasks. Pascal microarchitecture https://devblogs.nvidia.com/inside-pascal/gp100_block_diagram-2/ Pascal microarchitecture https://devblogs.nvidia.com/inside-pascal/gp100_sm_diagram/ GeForce GTX 1080 • Microarchitecture: Pascal. • DRAM: 8 GB GDDR5X at 10000 MHz. • SMs: 20. • Memory bandwidth: 320 GB/s. • CUDA cores: 2560. • L2 Cache: 2048 KB. • Clock (base/boost): 1607/1733 MHz. • L1 Cache: 48 KB per SM. • GFLOPs: 8873. • Shared memory: 96 KB per SM. GPU and multicore CPU architectures. Algorithm mapping • GPU and multicore CPU processing boards • Graphics cards • NVIDIA Jetson TX2 • NVIDIA Jetson Xavier • GPU programming • Algorithm mapping: • Convolutions ARM Cortex-A57: High-End ARMv8 CPU • ARMv8 architecture • Architecture evolution that extends ARM’s applicability to all markets. • Full ARM 32-bit compatibility, streamlined 64-bit capability. -

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4

Computer Hardware Architecture Lecture 4 Manfred Liebmann Technische Universit¨atM¨unchen Chair of Optimal Control Center for Mathematical Sciences, M17 [email protected] November 10, 2015 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Reading List • Pacheco - An Introduction to Parallel Programming (Chapter 1 - 2) { Introduction to computer hardware architecture from the parallel programming angle • Hennessy-Patterson - Computer Architecture - A Quantitative Approach { Reference book for computer hardware architecture All books are available on the Moodle platform! Computer Hardware Architecture 1 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 UMA Architecture Figure 1: A uniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory is the same for all cores in the system! Computer Hardware Architecture 2 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 NUMA Architecture Figure 2: A nonuniform memory access (UMA) multicore system Access times to main memory differs form core to core depending on the proximity of the main memory. This architecture is often used in dual and quad socket servers, due to improved memory bandwidth. Computer Hardware Architecture 3 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 Cache Coherence Figure 3: A shared memory system with two cores and two caches What happens if the same data element z1 is manipulated in two different caches? The hardware enforces cache coherence, i.e. consistency between the caches. Expensive! Computer Hardware Architecture 4 Manfred Liebmann November 10, 2015 False Sharing The cache coherence protocol works on the granularity of a cache line. If two threads manipulate different element within a single cache line, the cache coherency protocol is activated to ensure consistency, even if every thread is only manipulating its own data. -

V850ES/SA2, V850ES/SA3 32-Bit Single-Chip Microcontrollers

To our customers, Old Company Name in Catalogs and Other Documents On April 1st, 2010, NEC Electronics Corporation merged with Renesas Technology Corporation, and Renesas Electronics Corporation took over all the business of both companies. Therefore, although the old company name remains in this document, it is a valid Renesas Electronics document. We appreciate your understanding. Renesas Electronics website: http://www.renesas.com April 1st, 2010 Renesas Electronics Corporation Issued by: Renesas Electronics Corporation (http://www.renesas.com) Send any inquiries to http://www.renesas.com/inquiry. Notice 1. All information included in this document is current as of the date this document is issued. Such information, however, is subject to change without any prior notice. Before purchasing or using any Renesas Electronics products listed herein, please confirm the latest product information with a Renesas Electronics sales office. Also, please pay regular and careful attention to additional and different information to be disclosed by Renesas Electronics such as that disclosed through our website. 2. Renesas Electronics does not assume any liability for infringement of patents, copyrights, or other intellectual property rights of third parties by or arising from the use of Renesas Electronics products or technical information described in this document. No license, express, implied or otherwise, is granted hereby under any patents, copyrights or other intellectual property rights of Renesas Electronics or others. 3. You should not alter, modify, copy, or otherwise misappropriate any Renesas Electronics product, whether in whole or in part. 4. Descriptions of circuits, software and other related information in this document are provided only to illustrate the operation of semiconductor products and application examples. -

Parallel Generation of Image Layers Constructed by Edge Detection

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 13, Number 10 (2018) pp. 7323-7332 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Speed Up Improvement of Parallel Image Layers Generation Constructed By Edge Detection Using Message Passing Interface Alaa Ismail Elnashar Faculty of Science, Computer Science Department, Minia University, Egypt. Associate professor, Department of Computer Science, College of Computers and Information Technology, Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Abstract A. Elnashar [29] introduced two parallel techniques, NASHT1 and NASHT2 that apply edge detection to produce a set of Several image processing techniques require intensive layers for an input image. The proposed techniques generate computations that consume CPU time to achieve their results. an arbitrary number of image layers in a single parallel run Accelerating these techniques is a desired goal. Parallelization instead of generating a unique layer as in traditional case; this can be used to save the execution time of such techniques. In helps in selecting the layers with high quality edges among this paper, we propose a parallel technique that employs both the generated ones. Each presented parallel technique has two point to point and collective communication patterns to versions based on point to point communication "Send" and improve the speedup of two parallel edge detection techniques collective communication "Bcast" functions. The presented that generate multiple image layers using Message Passing techniques achieved notable relative speedup compared with Interface, MPI. In addition, the performance of the proposed that of sequential ones. technique is compared with that of the two concerned ones. In this paper, we introduce a speed up improvement for both Keywords: Image Processing, Image Segmentation, Parallel NASHT1 and NASHT2. -

CS650 Computer Architecture Lecture 10 Introduction to Multiprocessors

NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture CS650 Computer Architecture Lecture 10 Introduction to Multiprocessors and PC Clustering Andrew Sohn Computer Science Department New Jersey Institute of Technology Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 1/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Key Issues Run PhotoShop on 1 PC or N PCs Programmability • How to program a bunch of PCs viewed as a single logical machine. Performance Scalability - Speedup • Run PhotoShop on 1 PC (forget the specs of this PC) • Run PhotoShop on N PCs • Will it run faster on N PCs? Speedup = ? Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 2/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Types of Multiprocessors Key: Data and Instruction Single Instruction Single Data (SISD) • Intel processors, AMD processors Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) • Array processor • Pentium MMX feature Multiple Instruction Single Data (MISD) • Systolic array • Special purpose machines Multiple Instruction Multiple Data (MIMD) • Typical multiprocessors (Sun, SGI, Cray,...) Single Program Multiple Data (SPMD) • Programming model Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 3/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Shared-Memory Multiprocessor Processor Prcessor Prcessor Interconnection network Main Memory Storage I/O Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 4/15 12/7/2003 A. Sohn NJIT Computer Science Dept CS650 Computer Architecture Distributed-Memory Multiprocessor Processor Processor Processor IO/S MM IO/S MM IO/S MM Interconnection network IO/S MM IO/S MM IO/S MM Processor Processor Processor Lecture 10: Intro to Multiprocessors/Clustering 5/15 12/7/2003 A. -

Superscalar Fall 2020

CS232 Superscalar Fall 2020 Superscalar What is superscalar - A superscalar processor has more than one set of functional units and executes multiple independent instructions during a clock cycle by simultaneously dispatching multiple instructions to different functional units in the processor. - You can think of a superscalar processor as there are more than one washer, dryer, and person who can fold. So, it allows more throughput. - The order of instruction execution is usually assisted by the compiler. The hardware and the compiler assure that parallel execution does not violate the intent of the program. - Example: • Ordinary pipeline: four stages (Fetch, Decode, Execute, Write back), one clock cycle per stage. Executing 6 instructions take 9 clock cycles. I0: F D E W I1: F D E W I2: F D E W I3: F D E W I4: F D E W I5: F D E W cc: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 • 2-degree superscalar: attempts to process 2 instructions simultaneously. Executing 6 instructions take 6 clock cycles. I0: F D E W I1: F D E W I2: F D E W I3: F D E W I4: F D E W I5: F D E W cc: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Limitations of Superscalar - The above example assumes that the instructions are independent of each other. So, it’s easily to push them into the pipeline and superscalar. However, instructions are usually relevant to each other. Just like the hazards in pipeline, superscalar has limitations too. - There are several fundamental limitations the system must cope, which are true data dependency, procedural dependency, resource conflict, output dependency, and anti- dependency.