Recollections by Albert J. "A.J." Willett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

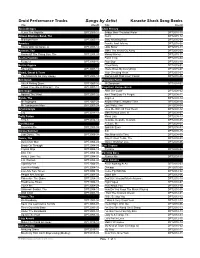

Druid Performance Tracks Karaoke

Druid Performance Tracks Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Alicia Bridges Elvis Presley I Love The Nightlife DPT2009-14 Bridge Over Troubled Water DPT2015-15 Allman Brothers Band, The Don't DPT2015-12 Midnight Rider DPT2005-11 Early Morning Rain DPT2015-09 America Frankie And Johnny DPT2015-05 Horse With No Name, A DPT2005-12 Little Sister DPT2015-13 Animals, The Make The World Go Away DPT2015-02 House Of The Rising Sun, The DPT2005-05 Money Honey DPT2015-11 Aretha Franklin Patch It Up DPT2015-04 Respect DPT2009-10 Poor Boy DPT2015-10 Bertie Higgins Proud Mary DPT2015-01 Key Largo DPT2007-12 There Goes My Everything DPT2015-07 Blood, Sweat & Tears Your Cheating Heart DPT2015-03 You Made Me So Very Happy DPT2005-13 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' DPT2015-06 Bob Dylan Emmylou Harris Like A Rolling Stone DPT2007-10 Mr Sandman DPT2014-01 Times They Are A-Changin', The DPT2007-11 Engelbert Humperdinck Bob Seger After The Lovin' DPT2008-02 Against The Wind DPT2007-02 Am I That Easy To Forget DPT2008-11 Byrds, The Angeles DPT2008-14 Mr Bojangles DPT2007-09 Another Place, Another Time DPT2008-10 Mr Tambourine Man DPT2007-08 Last Waltz, The DPT2008-04 Crystal Gayle Love Me With All Your Heart DPT2008-12 Cry DPT2014-11 Man Without Love, A DPT2008-07 Dolly Parton Mona Lisa DPT2008-13 9 To 5 DPT2014-13 Quando, Quando, Quando DPT2008-05 Don McLean Release Me DPT2008-01 American Pie DPT2007-05 Spanish Eyes DPT2008-03 Donna Summer Still DPT2008-15 Last Dance, The DPT2009-04 This Moment In Time DPT2008-09 Doors, The Way It Used To Be, The DPT2008-08 Back Door Man DPT2004-02 Winter World Of Love DPT2008-06 Break On Through DPT2004-05 Eric Clapton Crystal Ship DPT2004-12 Cocaine DPT2005-02 End, The DPT2004-06 Fontella Bass Hello, I Love You DPT2004-07 Rescue Me DPT2009-15 L.A. -

Record Collectibles

Unique Record Collectibles 3-9 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in gold vinyl with 7 inch Hound Dog picture sleeve embedded in disc. The idea was Elvis then and now. Records that were 20 years apart molded together. Extremely rare, one of a kind pressing! 4-2, 4-3 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-3 Elvis As Recorded at Madison 3-11 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 Made in black and blue vinyl. Side A has a Square Garden AFL1-4776 Made in blue vinyl with blue or gold labels. picture of Elvis from the Legendary Performer Made in clear vinyl. Side A has a picture Side A and B show various pictures of Elvis Vol. 3 Album. Side B has a picture of Elvis from of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the Aloha playing his guitar. It was nicknamed “Dancing the same album. Extremely limited number from Hawaii album. Side B has a picture Elvis” because Elvis appears to be dancing as of experimental pressings made. of Elvis from the inner sleeve of the same the record is spinning. Very limited number album. Very limited number of experimental of experimental pressings made. Experimental LP's Elvis 4-1 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 3-8 Moody Blue AFL1-2428 4-10, 4-11 Elvis Today AFL1-1039 Made in blue vinyl. Side A has dancing Elvis Made in gold and clear vinyl. Side A has Made in blue vinyl. Side A has an embedded pictures. Side B has a picture of Elvis. Very a picture of Elvis from the inner sleeve of bonus photo picture of Elvis. -

Elvis Presley Greatest Hits 6 Lp

1 / 4 Elvis Presley Greatest Hits 6 Lp 7 LPs in good condition Box in bad condition Comes with Elvis book about his life Collection only fr.. (#181: 19 February 1977, 6 weeks) For the more hardcore Elvis fan, also, The 50 Greatest Hits is an essential purchase, offering almost all of the finest tracks .... 19 Jul 2021 — Free 2-day shipping. Buy Elvis Presley - 50 Greatest Hits - Vinyl at Walmart.com.. Elvis presley greatest hits in vendita ✓ Elvis 30 1 Hits (Legacy Vinyl): 23,55 ... ELVIS PRESLEY's raro Greatest Hits puzzle 6 Lp box usato Palermo .... Moody Blue guitar chords and lyrics, as performed by Elvis Presley. ... Buy The Moody Blues - In Search of the Lost Chord [LP] [180 Gram Vinyl, .... 80s Music Explosion!, AM Gold, Big Bands, Body & Soul (6), Body Talk, ... **Classic Rock Greatest Hits 60s,70s,80s - Best Classic Rock Songs Of All T Best ... Elvis Presley- Elvis Presley's Greatest Hits.1978 UK 6LP Box Set +Bonus LP+ More. EUR 98.66. EUR 58.97 postage. or Best Offer .... The 50 Greatest Hits is a compilation album by American recording artist Elvis Presley, originally released on November 18, 2000.. Elvis Presley Greatest Hits | Elvis Presley Overview. Music Career, Ed Sullivan Show, Out of The Army, Number Ones.. ELVIS PRESLEY- THE Greatest Hits READERS DIGEST BOX SET 6-LP (Best of) 50s 60s - £17.99. FOR SALE! OUR REF- LP Lp 38701ELVIS PRESLEY- The Greatest Hits .... Shawn Klush, who played Elvis Presley on HBO's acclaimed "Vinyl" series, ... when 6 million viewers tuned in to see him crowned 'The World's Greatest Elvis' ... -

MY BERKSHIRE B Y

MY BERKSHIRE b y Eleanor F . Grose OLA-^cr^- (\"1S MY BERKSHIRE Childhood Recollections written for my children and grandchildren by Eleanor F. Grose POSTSCIPT AND PREFACE Instead of a preface to my story, I am writing a postscript to put at the beginning! In that way I fulfill a feeling that I have, that now that I have finished looking back on my life, I am begin' ning again with you! I want to tell you all what a good and satisfying time I have had writing this long letter to you about my childhood. If it hadn’t been for you, I wouldn’t have had the fun of thinking about and remembering and trying to make clear the personalities of my father and mother and making them integrated persons in some kind of perspective for myself as well as for you—and I have en joyed it all very much. I know that I will have had the most fun out of it, but I don’t begrudge you the little you will get! It has given me a very warm and happy feeling to hear from old friends and relatives who love Berkshire, and to add their pleasant memo ries to mine. But the really deep pleasure I have had is in linking my long- ago childhood, in a kind of a mystic way, in my mind, with you and your future. I feel as if I were going on with you. In spite of looking back so happily to old days, I find, as I think about it, that ever since I met Baba and then came to know, as grown-ups, my three dear splendid children and their children, I have been looking into the future just as happily, if not more so, as, this win ter, I have been looking into the past. -

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG

Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Adam & Evil After Loving You Ain't That Lovin' You Baby All I Needed Was Rain All Shook Up All Shook Up (Live) All That I Am Almost Almost Always True Almost In Love Always On My Mind Am I Ready Amazing Grace America The Beautiful American Trilogy And I Love You So And The Grass Won't Pay No Mind Angel Any Day Now Any Place In Paradise Any Way You Want Me Anyone Could Fall In Love With You Anything That's Part Of You Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Lonesome Tonight Are You Sincere As Long As I Have You Ask Me Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Baby I Don't Care Baby Let's Play House Beach Boy Blues Beyond The Bend Big Boots Big Boss Man Big Hunk O' Love, A (Live) Aloha Concert Big Love, Big Heartache Bitter They Are, Harder They Fall Blue Christmas Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain Blue Hawaii Blue Moon Blue Suede Shoes Blue Suede Shoes Blueberry Hill Blueberry Hill/I Can't Stop Loving (Medley) Bosom Of Abraham Bossa Nova Baby Boy Like Me, A Girl Like You, A Bridge Over Troubled Water (Live) Bringin' It Back Burning Love (Live) Aloha Concert By & By Can't Help Falling In Love Change Of Habit Charro Cindy, Cindy Clean Up Your Own Back Yard C'mon Everybody Elvis Mega Karaokepakke CDG Crawfish Cross My Heart, Hope To Die Crying In The Chapel Danny Boy Devil In Disguise Didja Ever Dirty Dirty Feeling Dixieland Rock Do Not Disturb Do You Know Who I Am Doin' The Best I Can Don't Don't Ask Me Why Don't Be Cruel Don't Cry Daddy Don't Leave Me Now Don't Think Twice Don'tcha Think It's Time Down By The Riverside/When The Saints -

Kidd Galahad Elvis Tribute Artist Set List Kidd Galahad Is an Elvis

Kidd Galahad Elvis Tribute Artist Set List Kidd Galahad is an Elvis Tribute Artist with a vast set list, covering all eras of Elvis' music. Listed here is a small list we have compiled of the songs he performs. Please feel to choose your own set list for your event. All Shook Up Guitar Man (Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear Always On My Mind Heartbreak Hotel Little Less Conversation An American Trilogy Heart Of Rome Little Sister And The Grass Won't Pay No Mind Hey Jude Life Are You Lonesome Tonight Hound Dog Love Letters Big Boots Hurt Love Me Big Boss Man If I Get Home On Christmas Day Love Me Tender Big Hunk O' Love I Can't Stop Loving You Mama Liked The Roses Blue Christmas I Got A Woman (Marie's The Name) His Latest Flame Bossa Nova Baby I Just Can't Help Believin' Mary In The Morning Bridge Over Troubled Water I Want You, I Need You, I Love You Maybellene Burning Love I'll Remember You Memories Can't Help Falling In Love Impossible Dream Moody Blue Don't I'm Leavin' Mr Songman Don't Be Cruel I'm So Lonely I Could Cry My Babe Don't Cry Daddy In The Ghetto My Baby Left Me Fever It's Impossible My Boy Fool It's Now Or Never My Way For The Good Times It's Easy For You Mystery Train For The Heart I've Lost You Next Step Is Love For Ol' Times Sake It's Your Baby, You Rock It! (Now & Then There's) A Fool Such As I GI Blues Jailhouse Rock Old MacDonald Girl Of My Best Friend Johnny B. -

WDAM Radio's History of Elvis Presley

Listeners Guide To WDAM Radio’s History of Elvis Presley This is the most comprehensive collection ever assembled of Elvis Presley’s “charted” hit singles, including the original versions of songs he covered, as well as other artists’ hit covers of songs first recorded by Elvis plus songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis! More than a decade in the making and an ongoing work-in-progress for the coming decades, this collection includes many WDAM Radio exclusives – songs you likely will not find anywhere else on this planet. Some of these, such as the original version of Muss I Denn (later recorded by Elvis as Wooden Heart) and Liebestraum No. 3 later recorded by Elvis as Today, Tomorrow And Forever) were provided by academicians, scholars, and collectors from cylinders or 78s known to be the only copies in the world. Once they heard about this WDAM Radio project, they graciously donated dubs for this archive – with the caveat that they would never be duplicated for commercial use and restricted only to musicologists and scholarly purposes. This collection is divided into four parts: (1) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S singles hits in chronological order – (2) All of Elvis Presley’s charted U S and U K singles, the original versions of these songs by other artists, and hit versions by other artists of songs that Elvis Presley recorded first or had a cover hit – in chronological order, along with relevant parody/answer tunes – (3) Songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley – mostly, but not all in chronological order – and (4) X-rated or “adult-themed” songs parodying, saluting, or just mentioning Elvis Presley. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

High School | 9Th–12Th Grade

High School | 9th–12th Grade American History 1776The Hillsdale Curriculum The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum 9th–12th Grade HIGH SCHOOL American History 2 units | 45–50-minute classes OVERVIEW Unit 1 | The American Founding 15–19 classes LESSON 1 1763–1776 Self–Government or Tyranny LESSON 2 1776 The Declaration of Independence LESSON 3 1776–1783 The War of Independence LESSON 4 1783–1789 The United States Constitution Unit 2 | The American Civil War 14–18 classes LESSON 1 1848–1854 The Expansion of Slavery LESSON 2 1854–1861 Toward Civil War LESSON 3 1861–1865 The Civil War LESSON 4 1865–1877 Reconstruction 1 Copyright © 2021 Hillsdale College. All Rights Reserved. The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum American History High School UNIT 1 The American Founding 1763–1789 45–50-minute classes | 15–19 classes UNIT PREVIEW Structure LESSON 1 1763–1776 Self-Government or Tyranny 4–5 classes p. 7 LESSON 2 1776 The Declaration of Independence 2–3 classes p. 14 LESSON 3 1776–1783 The War of Independence 3–4 classes p. 23 LESSON 4 1783–1789 The United States Constitution 4–5 classes p. 29 APPENDIX A Study Guide, Test, and Writing Assignment p. 41 APPENDIX B Primary Sources p. 59 Why Teach the American Founding The beginning is the most important part of any endeavor, for a small change at the beginning will result in a very different end. How much truer this is of the most expansive of human endeavors: founding and sustaining a free country. The United States of America has achieved the greatest degree of freedom and prosperity for the greatest proportion of any country’s population in the history of humankind. -

Essays, Poetry, Stories, Artwork, and More the Creative Arts Magazine Of

Comet “Tales” Essays, Poetry, Stories, Artwork, and More The Creative Arts Magazine of Marionville Elementary and Middle School Students 2015-16 Foreword Welcome to the fourth publication of Comet “Tales,” the literary magazine that celebrates the creativity of Marionville students in grades 3-8. Thank you to all the teachers who submitted student writing and artwork. A link to an electronic (full color) version of this publication is available on our school website: www.marionville.us. The Editors, Cindy Mueller, PK-8 Librarian Ashley Mann, Middle School Communication Arts Jenna Unerstall, Middle School Communication Arts Cover Illustration by Jana Fulp, 4th A Publication of Marionville R-9 Schools Marionville, Missouri 65705 Elementary Principal: Greg Hopkins Middle School Principal: Shane Moseman Superintendent: Dr. Larry Brown Totem: Sofi Armfield, 5th Why so Many Colonists Died in Early Jamestown Why had so many colonists die in early Jamestown? Jamestown was the first permanent colony in America. Jamestown was located in Virginia and was founded around 1607. Many colonists died for several reasons in Jamestown’s early years, early years being around 1608 to 1612. Jamestown colonists died mainly because of three reasons. These reasons are the Powhatan, starvation and health/water. The first and main reason so many colonists died was due to health/water. Evidence shows that their main source of water, the James River, was also used to dispose of human waste, food scraps and even used to wash clothing. Instead of the waste being removed naturally, like the colonist had thought, it stayed and drastically damaged their health and food supply. -

Middle School English-Language Arts Resource Packet

Middle School English-Language Arts Resource Packet Packet Directions: As you read each passage… 1. Annotate (by highlighting, underlining, and/or writing notes on the passage) key details, vocabulary, etc. 2. Use annotations to complete the close reading activities below. (You may use notebook paper to replicate the charts below to complete.) 3. Answer questions that follow each passage. Activity 1a: K-W-L Chart (For non-fiction passages) K W L (What do you already (What do you want to (What did you learn after know?) know?) reading?) Activity 1b: Story Elements (For fiction passages) Events Problem/Challenge Character Response Dialogue (How does it affect the passage?) Resolution: 1 Middle School English-Language Arts Resource Packet Activity 2: Vocabulary Guide (Complete a chart for at least five words from each passage.) Word: Clues to word’s meaning: Definition in your own words: Definition: Activity 3a: Summarization (For non-fiction passages) Central Idea Summary of the Passage Activity 3b: Summarization (For fiction passages) Key Details Theme or Central Idea Summary 2 Middle School English-Language Arts Resource Packet Read the passage(s) below and answer the question(s) that follow. From Cameroon to New York 1 It’s been about a year now, and I am finally starting to feel more at home in Brooklyn, New York. My family moved here from Cameroon, a country in Africa. When we first arrived, I was overwhelmed by how fast people speak English here. Although I learned English in school in Cameroon, we spoke slowly, leaving a space between each word. On the streets of Brooklyn, all the words melt together into one. -

Full Song List by Song A

CODE SONG ARTIST TIME CAB1 123 Len Barry ‐ 2:30 CAB2 1234 Feist ‐ 3:02 CAB3 1973 JAMES BLUNT ‐ 3:56 CAB4 1985 Bowling for Soup ‐ 3:14 CAB5 1999 Prince 3:39 CAB6 (FAR FROM) HOME TIGA ‐ 2:51 CAB4682 (All Of A Sudden) My Hearts Sings Paul Anka 3:01 CAB7 (And She Said) Take Me Now Justin Timberlake ft Janet Jac ‐ 5:31 CAB8 (Can't Get My) Head Around You The Offspring ‐ 2:14 CAB9 (Don't) Give Hate A Dance Jamiroquai ‐ 3:48 CAB10 (Everybody) Get Up (Rogers Zap Roger ‐ 6:03 CAB4676 (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Sam Cooke 3:13 CAB4677 (If You Cry) True Love, True Love The Drifters 2:16 CAB4809 (It's Been A Long Time) Pretty Baby Gino & Gina 2:01 CAB4510 (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney 2:27 CAB4766 (There'll Be) Peace In The Valley (For Me) Elvis Presley 3:21 CAB11 (There's) Always Something The Sandie Shaw ‐ 2:42 CAB12 (They Long to Be) Close to You The Carpenters ‐ 4:31 CAB13 (When You Gonna) Give It Up To Various ‐ 4:03 CAB4358 (You've Got) The Magic Touch The Platters 2:26 CAB14 1 Thing Amerie Feat Eve ‐ 3:57 CAB15 1,2 Step Ciara feat Missy Elliott ‐ 3:17 CAB16 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters ‐ 3:06 CAB17 13, Storia D'oggi Al Bano 4:14 CAB18 15 Minut Projekt 15 Minut Projekt 6:55 CAB4418 16 Candles The Crests 2:51 CAB19 1983 (Eric Prydz Remix) Dirty South ‐ 3:15 CAB20 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue ‐ 2:52 CAB21 2 TIMES ANN LEE ‐ 3:46 CAB22 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc ‐ 3:46 CAB23 20 Miles Ray Brown And The Whispers ‐ 2:18 CAB24 22 STEPS DAMIEN LEITH ‐ 3:32 CAB25 24 MILA BACI LITTLE TON 2:48 CAB26 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 3:18 CAB27 3,2,1 Remix P‐MONEY FEAT.