The Rohingya Crisis: Past, Present and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

That Is Necessary

Belmont University Belmont Digital Repository Honors Theses Belmont Honors Program 4-20-2020 All That Is Necessary Jes Martinez Belmont University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/honors_theses Part of the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Jes, "All That Is Necessary" (2020). Honors Theses. 23. https://repository.belmont.edu/honors_theses/23 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Belmont Honors Program at Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL THAT IS NECESSARY written by Jes Martinez Based on Real Events DRAFT B [email protected] (703) 340-5100 TIGHT ON: an ANIMATED MAP of the world. It ZOOMS INTO INDIA and SOUTHEAST ASIA, c. 1050 AD. Then ZOOMS INTO the PAGAN EMPIRE. A WALL OF RED, the MONGOL INVASION, washes over the empire, from the North, c. 1287 AD. The RED DISSOLVES and various CITY-STATES sprout up, rising and falling as they war with each other. EMMA (V.O.) Myanmar’s diverse demographic landscape emerged out of centuries of migration, invasion, and internal turmoil. The city-states DISSOLVE into the rise and fall of dynasties: the PEGU, BAGO, and HANTHARWADDY DYNASTIES (1287-1599), the PINYA DYNASTY (1309-60), the SAGAING DYNASTY (1315-64), the INWA DYNASTY (1365-1555), the TAUNGOO DYNASTY (1486-1752), and the KONBAUNG DYNASTY (1752-1885). EMMA (V.O.) Britain colonized the region-- then called Burma-- and deepened ethno- religious resentments by establishing a system of indirect rule in which they empowered local leaders from the minority groups while suppressing the majority Buddhist Bamar, lighting the flame for the wildfire that Burman religious nationalism was to become. -

Atrocity Crimes Risk Assessment Series

ASIA PACIFIC CENTRE - RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT ATROCITY CRIMES RISK ASSESSMENT SERIES MYANMAR VOLUME 9 - NOVEMBER 2019 Acknowledgements This 2019 updated report was prepared by Ms Elise Park whilst undertaking a volunteer senior in- ternship at the Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect based at the School of Political Science and International Studies at The University of Queensland. We acknowlege the 2017 version author, Ms Ebba Jeppsson (a volunteer senior APR2P intern )and the preliminary background research undertaken in 2016 by volunteer APR2P intern Mr Joshua Appleton-Miles. These internships were supported by the Centre’s staff: Professor Alex Bellamy, Dr Noel Morada, and Ms Arna Chancellor. The Asia Pacific Risk Assessment series is produced as part of the activities of the Asia Pacific Cen- tre for the Responsibility to Protect (AP R2P). Photo acknowledgement: Rohingya refugees make their way down a footpath during a heavy monsoon downpour in Kutupalong refugee settlement, Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh. © UNHCR/David Azia.Map Acknowledgement: United Nations Car-tographic Section. Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect School of Political Science and International Studies The University of Queensland St Lucia Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Email: [email protected] http://www.r2pasiapacific.org/index.html LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AA Arakan Army AHA ASEAN Humanitarian Assistance ALA Arakan Liberation Army ARSA Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations EAO Ethnic Armed -

Village Tracts of Mrauk - U Township Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Mrauk - U Township Rakhine State 93°0’E 93°10’E 93°20’E Kyauk Kyat Taung U Pyi Lone Gyi Ei Vi Ti Kar Kyi 20°48’N 20°48’N Yar Pyin Hteik Wa Pyin Pauk Pin Kwin Sin Ke Shar Yay Kan Sauk Pyin Oe Htein Pyaing Cha Tha Pyay Ma Kyar Se Kan Ta u n g M y in t Shwe Kyin Cheik Chaung Pyin Oke Kan Bu Ywet Gwa Son Ma Nyoe Hpa Yar Gyi Tein Nyo Byoke Chaung Maw Taung Taik Wet Hla Lay Hnyin Kone Baung Taung Tin Htein Kan 20°40’N Way Thar Li Gone Kyun 20°40’N Sin Oe Pya Hla Than Thin Pan Kaing Chaung Ywar Haung Taw MRAUK - U Kin Chaung Ah Yet Thay Ma Htan Ma Rit Na Kan Pu Zun Hpe Mrauk-U Myet Yaik Kyun Bar Nyo Kin Seik Urban Pu Rein Cha Yar Shauk Ta w Bwe i Ku Lar Ka Pon Kyun Baung Dut Paung Htoke Ka Da Wa Tan Tin Pi Pin Yin Than Ta Yar Ku Toe Nan Kya 20°32’N Naung Min 20°32’N Ma Har Kon Baung Su Yit Chaung Kyay Htee Oke Kar Kyaw Pin Lel Lay Hnyin Thar Pyar Te Yin Thei Myaung Than Shin Pyin Bway Maung Hna Ma Let Pan Taw Bu Ta Lone Zee Zar Kywe Te Koke Ka Rit Htaunt Ah Kyee Kant Tha Ri Set Thar Ta w M a Let Kyein Than Chi Nga Me Pyin Ye Hpyar Chaung Pyaung Paw Nyaung Pin Lel Nan Tet Ah Lel Chaung Kyar Kan Chin Shin Yae Zee Pin Gyi Hpa Yar Myar Tha Baw Mandalay Magway Nyaung 20°24’N Pin Lel (Ku Thar Yar Kone 20°24’N Lar Pone) K Thu Nge Taw Bay of Bengal Rakhine Bago Nat Chaung Minbya Kilometers Ayeyarwady 0482 Yangon 93°0’E 93°10’E 93°20’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Road Village Tract Boundaries Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU Creation Date: 15 November 2010. -

Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao

ICS TRAVEL GROUP is one of the first international DMCs to open own offices in our destinations and has since become a market leader throughout the Mekong region, Indonesia and India. As such, we can offer you the following advantages: Global Network. Rapid Response. With a centralised reservations centre/head All quotation and booking requests are answered office in Bangkok and 7 sales offices. promptly and accurately, with no exceptions. Local Knowledge and Network. Innovative Online Booking Engine. We have operations offices on the ground at every Our booking and feedback systems are unrivalled major destination – making us your incountry expert in the industry. for your every need. Creative MICE team. Quality Experience. Our team of experienced travel professionals in Our goal is to provide a seamless travel experience each country is accustomed to handling multi- for your clients. national incentives. Competitive Hotel Rates. International Standards / Financial Stability We have contract rates with over 1000 hotels and All our operational offices are fully licensed pride ourselves on having the most attractive pricing and financially stable. All guides and drivers are strategies in the region. thoroughly trained and licensed. Full Range of Services and Products. Wherever your clients want to go and whatever they want to do, we can do it. Our portfolio includes the complete range of prod- ucts for leisure and niche travellers alike. ICS TRAVEL ICSGROUPTRAVEL GROUP Contents Introduction 3 Tours 4 Cruises 20 Hotels 24 Yangon 24 Mandalay 30 Bagan 34 Mount Popa 37 Inle Lake 38 Nyaung Shwe 41 Ngapali 42 Pyay 45 Mrauk U 45 Ngwe Saung 46 Excursions 48 Hotel Symbol: ICS Preferred Hotel Style Hotel Boutique Hotel Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao Lahe INDIA INDIA Myitkyina CHINA CHINA Bhamo Muse MYANMAR Mogok Lashio Hsipaw BANGLADESHBANGLADESH Mandalay Monywa ICS TRA VEL GR OUP Meng La Nyaung Oo Kengtung Mt. -

1 Submission to CEDAW Regarding Myanmar's Exceptional Report On

Submission to CEDAW regarding Myanmar’s Exceptional Report on the Situation of Women and Girls from Northern Rakhine State May 2018 Human Rights Watch and Fortify Rights welcome the opportunity to provide joint input into the November 2017 request by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) for an exceptional report from the Myanmar government on the situation of women and girls from northern Rakhine State. This submission outlines the findings of our organizations through several separate on-the-ground investigations in 2016, 2017, and 2018 that documented widespread human rights violations committed against ethnic Rohingya women and girls by Myanmar security forces. We have included an appendix of relevant publications by our organizations. Our organizations have documented numerous mass atrocity crimes—including widespread killings, torture, rape and other sexual violence, arbitrary arrests, and mass arson—committed by Myanmar’s army and other state security forces. Human Rights Watch has found that these atrocities against the Rohingya amount to crimes against humanity.1 Fortify Rights, along with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Allard K. Lowenstein Clinic at Yale Law School, found strong evidence of genocide being committed against the Rohingya.2 In November 2017, Pramila Patten, the United Nations special representative on sexual violence in conflict, said the Myanmar army’s widespread use of sexual violence against Rohingya women and girls was “a calculated tool of terror aimed -

MASSACRE by the RIVER Burmese Army Crimes Against Humanity in Tula Toli WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS MASSACRE BY THE RIVER Burmese Army Crimes against Humanity in Tula Toli WATCH Massacre by the River Burmese Army Crimes against Humanity in Tula Toli Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35614 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-35614 Massacre by the River Burmese Army Crimes against Humanity in Tula Toli Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 9 To the Burmese Government .................................................................................................... 9 To the -

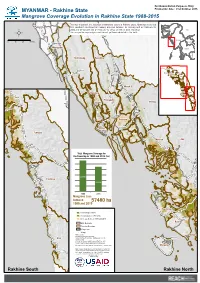

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

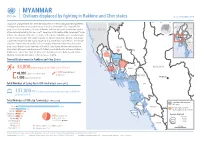

MYANMAR Civilians Displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin States As of 1 December 2019

MYANMAR Civilians displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin states As of 1 December 2019 Thousands of people have been internally displaced since the escalation of fighting between INDIA the Myanmar Armed Forces and the Arakan Army (AA) in December 2018. Nearly 45,000 INDIA people have fled insecurity to 131 sites in Rakhine and Chin states with an unknown number BANGLADESH CHINA of people being hosted by families. As of 1 December 2019, Rakhine State Government figures indicate that about 43,000 people are displaced in 119 sites in Rakhine State and operational partners report around 1,800 displaced people are living in 12 sites in Chin State. Population Nay Pyi Taw movements remain fluid with regular reports of displacement and some returns. The number THAILAND of people displaced by this conflict increased sharply in November when more than 9,000 people were displaced in the townships of Mrauk-U, Rathedaung, Myebon and Buthidaung. PALETWA Intensified fighting and new displacements further complicate the humanitarian situation in BUTHIDAUNG CHIN Rakhine State where more than 131,000 people, including stateless Rohingya and Kaman MANDALAY Muslims, remain displaced since sectarian violence in 2012. MAUNGDAW Recent Displacement in Rakhine and Chin States KYAUKTAW PONNAGYUN MAGWAY people displaced by conflict as of 1 Dec’19 MINBYA 44,800 MRAUK-U RATHEDAUNG + 9,000 newly displaced 43,000 displaced in Rakhine State in November RAKHINE SITTWE Magway 1,800 displaced in Chin State PAUKTAW Sittwe MYEBON Total Number of Long-Term IDPs in Camps -

The Rohingya Origin Story: Two Narratives, One Conflict

Combating Extremism SHAREDFACT SHEET VISIONS The Rohingya Origin Story: Two Narratives, One Conflict At the center of the Rohingya Crisis is a question about the group’s origin. It is in this identity, and the contrasting histories that the two sides claim (i.e., the Rohingya minority and the Buddhist government/some civilians), where religion and politics collide. Although often cast as a religious war, the contemporary conflict didn’t exist until World War II, when the minority Muslim Rohingya sided with British colonial rulers, while the Buddhist majority allied with the invading Japanese. However, it took years for the identity politics to fully take root. It was 1982, when the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship by law (For more on this, see “Q&A on the Rohingya Crisis & Buddhist Extremism in Myanmar”). Myanmarese army commander Senior General Min Aung Hlaing made it clear that Rohingya origin lay at the heart of the matter when, on September 16, 2017, he posted to Facebook a statement saying that the current military action against the Rohingya is “unfinished business” stemming back to the Second World War. He also stated, “They have demanded recognition as Rohingya, which has never been an ethnic group in Myanmar. [The] Bengali issue is a national cause and we need to be united in establishing the truth.”i This begs the question, what is the truth? There is no simple answer to this question. At the present time, there are two dominant, opposing narratives regarding the Rohingya ethnic group’s history: one from the Rohingya perspective, and the other from the neighboring Rakhine and Bamar peoples. -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations..