3. Wales a Publication from the Bennett Institute for Public Policy Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Flu Immunisation Dates – 2019

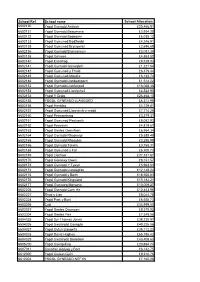

30/09/19 WK 1 DATE Thursday YBC 03/10/2019 The Bridge 03/10/2019 Friday Heronsbridge 04/10/2019 07/10/19 WK 2 Monday Greenfield 07/10/2019 YGG Llyn- y-Forwyn 07/10/2019 Ysgol Ty Coch 07/10/2019 Litchard 07/10/2019 Tuesday Park Lane 08/10/2019 Hendreforgan Primary 08/10/2019 PenyFai 08/10/2019 Wednesday Aberdare CIW 09/10/2019 Dolau Primary 09/10/2019 Bryncethin 09/10/2019 Thursday Troedyrhiw primary 10/10/2019 Glenboi primary 10/10/2019 Ysgol Hen felin 10/10/2019 Parclewis Primary 10/10/2019 Pencoed 10/10/2019 Friday Parc Primary 11/10/2019 Gwauncelyn Primary 11/10/2019 14/10/19 WK 3 Monday Dowlais Primary + PRU 14/10/2019 Ynyshir Primary 14/10/2019 Llwycrwn Primary 14/10/2019 Nottage 14/10/2019 Tuesday ysgol santes tudfil 15/10/2019 Penderyn 15/10/2019 Pontrhondda primary 15/10/2019 Cefn Cribwr 15/10/2019 St Roberts 15/10/2019 Wednesday Abercynon community 16/10/2019 Llanhari Primary (Eng) 16/10/2019 Nantymoel 16/10/2019 Thursday Cyfarthfa Infants* 17/10/2019 Cyfarthfa junior* 17/10/2019 Penywaun primary 17/10/2019 Penpych primary 17/10/2019 Craig-yr-Hesg Primary 17/10/2019 AM Cefn Primary 17/10/2019 PM Maes Yr Haul 17/10/2019 Friday Gellifaelog 18/10/2019 Ynysyboeth 18/10/2019 Porth Community 18/10/2019 21/10/19 WK 4 Monday YGG Rhyd y Grug 21/10/2019 Abernant primary 21/10/2019 AM Llwydcoed 21/10/2019 PM Penrhys Primary 21/10/2019 AM Tai Unit 21/10/2019 PM Tonysguboriau Primary 21/10/2019 Porthcawl 21/10/2019 Afon Y Felin 21/10/2019 Tuesday Edwardsville Nursery 22/10/2019 Edwardsville 22/10/2019 St Margarets 22/10/2019 Williamstown -

Deposit Draft Local Development Plan 2006 - 2021 Preserving Our Heritage • Building Our Future Contents

Deposit Draft Local Development Plan 2006 - 2021 Preserving Our Heritage • Building Our Future Contents Chapter 1 Introduction and Context ......................................3 Chapter 7 Monitoring and Review Framework....................117 Introduction...................................................................3 Appendix 1 Detailed Allocations ..........................................121 Structure of document ..................................................4 a) Housing Allocations .............................................121 Key facts about Rhondda Cynon Taf.............................5 b) Employment Allocations......................................128 Links to other Strategies................................................5 c) Retail Allocations .................................................130 National Planning Policy and Technical Advice.........11 d) Major Highway Schemes......................................131 How to use the document...........................................15 e) Sites of Important Nature Conservation Chapter 2 Key Issues in Rhondda Cynon Taf .........................17 and Local Nature Reserves ..................................133 Chapter 3 Vision and Objectives ..........................................21 Appendix 2 Statutory Designations.......................................137 Chapter 4 Core Strategy.......................................................25 Appendix 3 Local Development Plan Evidence Base..............139 Key Diagram ................................................................28 -

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to September

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-December 2020 Primary schools All Saints R.C. Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Blaen-Y-Cwm C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Coed -y- Garn Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Deighton Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Sofrydd C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Illtyd's Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Mary's Roman Catholic - Brynmawr Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Willowtown Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ysgol Bro Helyg Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ystruth Primary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Afon-Y-Felin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Archdeacon John Lewis Bridgend County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Brackla Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryncethin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryntirion Infants School Bridgend County Borough Council Cefn Glas Infant School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Cwmfelin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend -

Settings Participating in Designed to Smile, Cwm Taf University Health Board (July 2017) Merthyr Tydfil

Settings participating in Designed to Smile, Cwm Taf University Health Board (July 2017) Merthyr Tydfil Bedlinog Community Primary Bobl Bach Pre-school Building Blocks Preschool Busy Bees Pre School Caedraw Primary Cyfarthfa Park Primary School Cylch Meithrin Pentrebach (ICC Merthyr) Cylch Meirthin Treharris Cylch Meithrin Twyncarmel Dowlais Primary School Dwy Lo Bach Pre-School Edwardsville Primary School and Nursery Funtazia Day Nursery (Cwm Golau) Funtazia Day Nursery (Prince Charles Hospital) Galon Uchaf Pre School Gellifaelog Primary School Goetre Primary School Gurnos Nursery Gwaunfarren Primary School Heolgerrig Community School Here We Grow Day Nursery Kerry Anne Lewton Childminder Little Cubs (Now Llwynog Bychain Bedllwynog) Little Lambs Pentrebach (was Footsteps) Little Lambs Treharris Little Rascals Myra Greenhaf Childminder Nursery Rhymes Community Playgroup Merthyr Tydfil (continued) Pantysgallog Primary School Pila Pala Bilingual Day Nursery Plant Bach and Penydarren Flying Start Seren Bach Flying Start Pre-School St Aloysios RC Primary St Illtyd's RC St Mary’s RC Primary Tiny Treasures Toddlers@ Coed-Y-Dderwen Troedyrhiw Early Days Support (TEDS) Trefechan Toddlers Pre School Treharris Nursery (Edwardsville Primary Nursery Dept) Trelewis Playgroup Trelewis Primary School Trinity Childcare and Family Centre Troedyrhiw Primary School Twynyrodyn Community School Ynysowen Community Primary School Ysgol Gynradd Coed y Dderwen Ysgol Gynradd Gymraeg Rhyd-y-Grug Ysgol Gynradd Gymraeg Santes Tudful Ysgol Y Graig Nursery (Trefechan -

Evaluation of the Lateral Flow Device Testing Pilot for COVID-19 in Merthyr Tydfil and the Lower Cynon Valley

2020 Evaluation of the Lateral Flow Device Testing Pilot for COVID-19 in Merthyr Tydfil and the lower Cynon Valley MERTHYR TYDFIL COUNTY BOROUGH & LOWER CYNON VALLEY (RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH) SECTION CONTENT PAGE 1 Foreword 3 2 Executive summary 5 3 Introduction 9 3.1 Purpose 3.2 Pilot aims and objectives 3.3 Demography of pilot areas 3.3.1 Deprivation in pilot areas 3.3.2 Black and ethnic minority populations 3.4 Epidemiology of COVID-19 in the pilot areas 3.4.1 Positivity rates and lockdowns 3.5 Testing strategy 3.6 Hypothesis to test through assessment of mass testing 4 Governance, planning and implementation 17 4.1 Governance 4.2 Planning 4.3 Implementation 5 Logistics 26 5.1 Community based testing 5.1.1 Home testing arrangements 5.2 Contact tracing 5.3 Protect 5.3.1 Cwm Taf Morgannwg Self Isolation Helpline 6 Schools based testing – Merthyr Tydfil and lower Cynon Valley 37 6.1 Communication and engagement 6.2 Secondary school mass testing – Merthyr Tydfil 6.3 Secondary school mass testing – lower Cynon Valley 6.4 Resources 6.4.1 Workforce resources 6.4.2 Logistical resources 6.4.3 Financial resources 6.5 Testing and analysis of uptake outcomes 6.5.1 Uptake 6.5.2 Positivity rate by age group 6.6 Comparisons, learning from other areas 6.7 Systems and process working 7 Resources 53 7.1 Workforce resources 7.2 Logistical resources 7.2.1 Physical infrastructure 7.2.2 Equipment and support services 1 | P a g e 7.3 Financial resources 8 Analysis of testing uptake and outcomes 65 8.1 Uptake of testing 8.1.2 Age and gender 8.1.3 -

61 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

61 bus time schedule & line map 61 Aberdare - Pontypridd View In Website Mode The 61 bus line (Aberdare - Pontypridd) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aberdare: 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM (2) Pontypridd: 5:57 AM - 7:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 61 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 61 bus arriving. Direction: Aberdare 61 bus Time Schedule 58 stops Aberdare Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Bus Station 5, Pontypridd Tuesday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Corn Stores, Pontypridd Wednesday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Hollies, Pontshonnorton Thursday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Bryn Olwg, Pontshonnorton Friday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Bryn Olwg, Pontypridd Saturday 7:05 AM - 8:45 PM Royal Oak Inn, Pontshonnorton Coronation Terrace, Pontypridd Community Norton Bridge Methodists, Pontshonnorton 61 bus Info Kings Hill, Cilfynydd Direction: Aberdare Cilfynydd Road, Pontypridd Community Stops: 58 Trip Duration: 48 min Albion Flats, Cilfynydd Line Summary: Bus Station 5, Pontypridd, Corn Stores, Pontypridd, Hollies, Pontshonnorton, Bryn Commercial Hotel, Cilfynydd Olwg, Pontshonnorton, Royal Oak Inn, Pontshonnorton, Norton Bridge Methodists, Cilfynydd Inn, Cilfynydd Pontshonnorton, Kings Hill, Cilfynydd, Albion Flats, Cilfynydd, Commercial Hotel, Cilfynydd, Cilfynydd Inn, Cilfynydd, Travellers Rest, Abercynon, Navigation Travellers Rest, Abercynon Park, Abercynon, Imperial, Abercynon, Station Road, Abercynon, Top Of the Hill, Abercynon, Albert House, Navigation Park, Abercynon Abercynon, -

The Degree of Mark Master Masons

THE DEGREE OF MARK MASTER MASONS All communications to be addressed to: M. A. Jones Mark Provincial Office Bridgend Masonic Hall Coychurch Road Bridgend CF31 2AP Tel: 02920 490555 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.southwalesmarkmastermasons.co.uk 302 THE EXECUTIVE R.W.Bro. Thomas Richard Eirian Jones Provincial Grand Master W.Bro. Dr Paul Richard Calderwood PGSD W.Bro. Philip William Davies PGJD Deputy Provincial Grand Master Assistant Provincial Grand Master 303 The Mark Degree is under the control of the Grand Lodge of Mark Master Masons of England and Wales and its Districts and Lodges Overseas. It has many similar associations with the old opera- tive system of Freemasonry. The ritual is founded upon ancient Craft legends of this operative system and reflects portions of Biblical History that are far earlier than other degrees. It deals with events before or at the building of King Solomon’s Temple and the problems that arose during its construction. It was found necessary to ensure completeness and perfect accuracy in all departments of the work and to establish a system of grades amongst the vast number of work- men employed, under which each member of each grade marked his work with some particular mark or symbol thereby enabling the overseers to know the hand which prepared each particular piece of work. Thus a very early system for “Quality Control” and ensuring “Value for Money” was established. In the old Guilds the ceremony of selecting and registering a Mark by newly admitted Craftsmen was second in importance only to that of his first admission into the Society. -

School Ref School Name School Allocation 6602130 Ysgol Gynradd

School Ref School name School Allocation 6602130 Ysgol Gynradd Amlwch £20,466.91 6602131 Ysgol Gynradd Beaumaris £3,934.20 6602132 Ysgol Gynradd Bodedern £6,038.12 6602133 Ysgol Gymuned Bodffordd £4,246.91 6602135 Ysgol Gymuned Bryngwran £2,696.68 6602136 Ysgol Gynradd Brynsiencyn £3,081.38 6602138 Ysgol Cemaes £4,853.52 6602140 Ysgol Esceifiog £8,529.83 6602141 Ysgol Gynradd Garreglefn £1,221.54 6602142 Ysgol Gymuned y Ffridd £6,379.44 6602145 Ysgol Gymuned Moelfre £6,122.74 6602146 Ysgol Gynradd Llanbedrgoch £1,514.22 6602152 Ysgol Gynradd Llanfairpwll £16,068.36 6602153 Ysgol Gymuned Llanfechell £4,543.90 6602154 Ysgol Y Graig £26,468.10 6602155 YSGOL GYNRADD LLANGOED £6,312.95 6602156 Ysgol Henblas £4,729.81 6602157 Ysgol Gymuned Llannerch-y-medd £7,774.26 6602160 Ysgol Pencarnisiog £3,379.31 6602161 Ysgol Gymuned Pentraeth £8,082.93 6602162 Ysgol Penysarn £4,819.67 6602163 Ysgol Santes Gwenfaen £6,954.34 6602164 Ysgol Gynradd Rhosneigr £5,355.49 6602165 Ysgol Gynradd Rhosybol £3,298.99 6602166 Ysgol Gynradd Talwrn £3,768.31 6602168 Ysgol Gymuned y Fali £6,700.73 6602169 Ysgol Llanfawr £27,331.67 6602170 Ysgol Goronwy Owen £8,151.57 6602173 Ysgol Gynradd Y Tywyn £5,963.03 6602174 Ysgol Gynradd Llandegfan £12,148.24 6602175 Ysgol Gynradd y Borth £18,565.83 6602176 Ysgol Gynradd Kingsland £15,182.21 6602177 Ysgol Gymraeg Morswyn £10,009.27 6602226 Ysgol Gynradd Corn Hir £10,843.96 6602227 Rhyd y Llan £8,044.78 6602228 Ysgol Parc y Bont £6,925.73 6603036 Cybi £35,999.05 6603037 Ysgol Santes Dwynwen £9,370.02 6603304 Ysgol Santes Fair -

60A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

60A bus time schedule & line map 60A Aberdare - Pontypridd View In Website Mode The 60A bus line (Aberdare - Pontypridd) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aberdare: 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM (2) Pontypridd: 6:09 AM - 6:02 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 60A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 60A bus arriving. Direction: Aberdare 60A bus Time Schedule 53 stops Aberdare Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Bus Station 5, Pontypridd Tuesday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Navigation Park, Abercynon Wednesday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Imperial, Abercynon Thursday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Walter Street, Abercynon Friday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Martins Close, Abercynon Community Saturday 7:35 AM - 7:05 PM Top Of the Hill, Abercynon Mountain Ash Road, Abercynon Community Albert House, Abercynon 60A bus Info Pontycynon, Pontcynon Direction: Aberdare Stops: 53 Level, Ynys-Boeth Trip Duration: 51 min Line Summary: Bus Station 5, Pontypridd, Ynysboeth, Ynys-Boeth Navigation Park, Abercynon, Imperial, Abercynon, Walter Street, Abercynon, Top Of the Hill, Abercynon, Albert House, Abercynon, Pontycynon, Pontcynon, Tynte Hotel, Tyntetown Level, Ynys-Boeth, Ynysboeth, Ynys-Boeth, Tynte Hotel, Tyntetown, Pentwyn Avenue, Tyntetown, Pentwyn Avenue, Tyntetown Pentwyn Avenue, Tyntetown, Pentwyn Bridge, Pentwyn Avenue, Abercynon Community Tyntetown, Infants School, Perthcelyn, Perthcelyn Stores, Perthcelyn, Post O∆ce, Perthcelyn, Mission Pentwyn Avenue, Tyntetown Hall, Miskin, Olde Royal Oak, Miskin, -

961 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

961 bus time schedule & line map 961 Aberdare - Pontypridd View In Website Mode The 961 bus line (Aberdare - Pontypridd) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Abercynon: 4:10 PM (2) Aberdare: 8:06 AM - 4:10 PM (3) Nantgarw: 7:43 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 961 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 961 bus arriving. Direction: Abercynon 961 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Abercynon Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:10 PM Bus Station 1, Aberdare Tuesday 4:10 PM The Full Moon, Aberdare Wednesday 4:10 PM Blaengwawr Inn, Aberaman Thursday 4:10 PM Henry Street, Aberdare Friday 4:10 PM The Brook, Aberaman Saturday Not Operational Plough Inn, Aberaman Mount Street, Aberaman Community Rock Inn, Aberaman 961 bus Info Swan, Aberaman Direction: Abercynon Brecon Street, Aberaman Community Stops: 46 Trip Duration: 42 min George Street, Aberaman Line Summary: Bus Station 1, Aberdare, The Full Moon, Aberdare, Blaengwawr Inn, Aberaman, The Clarence Terrace, Aberaman Brook, Aberaman, Plough Inn, Aberaman, Rock Inn, Cwrt Tre-Aman, Aberaman Community Aberaman, Swan, Aberaman, George Street, Aberaman, Clarence Terrace, Aberaman, Aberaman Aberaman Bridge, Aberaman Bridge, Aberaman, Home Bargains, Aberaman, Park View Terrace, Abercwmboi, Old Police Station, Home Bargains, Aberaman Abercwmboi, Cap Coch, Abercwmboi, Workmen's Hall, Abercwmboi, Terminus, Abercwmboi, The Park View Terrace, Abercwmboi Lodge, Fernhill, Glenboi Primary School, Fernhill, Fernhill Estate Middle, Fernhill, -

25 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

25 bus time schedule & line map 25 Fernhill - Pontypridd View In Website Mode The 25 bus line (Fernhill - Pontypridd) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fernhill: 7:50 PM (2) Mountain Ash: 6:25 PM (3) Perthcelyn: 8:25 PM (4) Pontypridd: 6:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 25 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 25 bus arriving. Direction: Fernhill 25 bus Time Schedule 36 stops Fernhill Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:50 PM Bus Station 5, Pontypridd Tuesday 7:50 PM Berw Road, Pontypridd Sion Street, Pontypridd Wednesday 7:50 PM Graig-Yr-Hesg, Trallwn Thursday 7:50 PM Graigyrhesg Road, Pontypridd Friday 7:50 PM White Bridge, Trallwn Saturday 7:50 PM Rogart Terrace, Glyn-Coch Glyncoch Terrace, Glyn-Coch Ynysybwl Road, Pontypridd Community 25 bus Info Direction: Fernhill Coed Y Cwm, Glyn-Coch Stops: 36 Trip Duration: 33 min New Road, Glyn-Coch Line Summary: Bus Station 5, Pontypridd, Berw Road, Pontypridd, Graig-Yr-Hesg, Trallwn, White Dan Y Cribyn, Ynys-Y-Bwl Bridge, Trallwn, Rogart Terrace, Glyn-Coch, Glyncoch New Road, Ynysybwl And Coed-Y-Cwm Community Terrace, Glyn-Coch, Coed Y Cwm, Glyn-Coch, New Road, Glyn-Coch, Dan Y Cribyn, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Greenbanks, Ynys-Y-Bwl Greenbanks, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Cribbyn Ddu, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Roberttown Hotel, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Augustus Street, Cribbyn Ddu, Ynys-Y-Bwl Ynys-Y-Bwl, Clive Terrace, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Heol-Y-Plwyf, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Cemetery, Ynys-Y-Bwl, Glanffrwd Cribyn-Ddu Street, Ynysybwl Terrace, Mynachdy, Terminus, Mynachdy, Post -

600 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

600 bus time schedule & line map 600 Aberdare - Cardiff via Mountain Ash, Abercynon, View In Website Mode Pontypridd The 600 bus line (Aberdare - Cardiff via Mountain Ash, Abercynon, Pontypridd) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aberdare: 11:47 AM - 7:52 PM (2) Cardiff Bus Station: 6:45 PM (3) Pontypridd: 10:15 AM - 9:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 600 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 600 bus arriving. Direction: Aberdare 600 bus Time Schedule 76 stops Aberdare Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 11:47 AM - 7:52 PM Monday Not Operational Philharmonic Jp, Cardiff Tuesday Not Operational Kingsway Gc, Cardiff Kingsway, Cardiff Wednesday Not Operational Corbett Road, Cathays Park Thursday Not Operational Friday Not Operational Blackweir Saturday Not Operational Maindy Stadium, Maindy Parkƒeld Place, Gabalfa Parkƒeld Place, Cardiff 600 bus Info North Road Clinic, Gabalfa Direction: Aberdare Stops: 76 Manor Way, the Philog Trip Duration: 36 min Line Summary: Philharmonic Jp, Cardiff, Kingsway Westƒeld Road, Whitchurch Gc, Cardiff, Corbett Road, Cathays Park, Blackweir, Maindy Stadium, Maindy, Parkƒeld Place, Gabalfa, North Road Clinic, Gabalfa, Manor Way, the Philog, Manor Rise, Whitchurch Westƒeld Road, Whitchurch, Manor Rise, Whitchurch, High School, Whitchurch, Tyn Y Parc Road, High School, Whitchurch Whitchurch, Brocastle Road, Whitchurch, Heol Y Northern Avenue, Cardiff Forlan, Whitchurch, Ynysangharad Park Gates, Pontypridd, Bus Station 4, Pontypridd, West Street, Tyn