Student Movements in Greece Regarding the Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Naming of Sea Areas in Modern Atlases and Implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan Case

Dual naming of sea areas in modern atlases and implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan case Rainer DORMELS* Dual naming is, to varying extents, present in nearly all atlases. The empirical research in this paper deals with the dual naming of sea areas in about 20 atlases from different nations in the years from 2006 to 2017. Objective, quality, and size of the atlases and the country where the atlases originated from play a key role. All these characteristics of the atlases will be taken into account in the paper. In the cases of dual naming of sea areas, we can, in general, differentiate between: cases where both names are exonyms, cases where both names are endonyms, and cases where one name is an endonym, while the other is an exonym. The goal of this paper is to suggest a typology of dual names of sea areas in different atlases. As it turns out, dual names of sea areas in atlases have different functions, and in many atlases, dual naming is not a singular exception. Dual naming may help the users of atlases to orientate themselves better. Additionally, dual naming allows for providing valuable information to the users. Regarding the naming of the sea between Korea and Japan present study has achieved the following results: the East Sea/Sea of Japan is the sea area, which by far showed the most use of dual naming in the atlases examined, in all cases of dual naming two exonyms were used, even in atlases, which allow dual naming just in very few cases, the East Sea/Sea of Japan is presented with dual naming. -

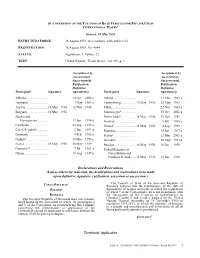

Unless Otherwise Indicated, the Declarations and Reservations Were Made Upon Definitive Signature, Ratification, Accession Or Succession.)

10. CONVENTION ON THE TAXATION OF ROAD VEHICLES FOR PRIVATE USE IN INTERNATIONAL TRAFFIC Geneva, 18 May 1956 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 18 August 1959, in accordance with article 6(2). REGISTRATION: 18 August 1959, No. 4844. STATUS: Signatories: 8. Parties: 23. TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 339, p. 3. Acceptance(A), Acceptance(A), Accession(a), Accession(a), Succession(d), Succession(d), Ratification, Ratification, Definitive Definitive Participant Signature signature(s) Participant Signature signature(s) Albania.........................................................14 Oct 2008 a Ireland..........................................................31 May 1962 a Australia....................................................... 3 May 1961 a Luxembourg.................................................18 May 1956 28 May 1965 Austria .........................................................18 May 1956 12 Nov 1958 Malta............................................................22 Nov 1966 a Belgium .......................................................18 May 1956 Montenegro5 ................................................23 Oct 2006 d Bosnia and Netherlands6.................................................18 May 1956 20 Apr 1959 Herzegovina1..........................................12 Jan 1994 d Norway ........................................................ 9 Jul 1965 a Cambodia.....................................................22 Sep 1959 a Poland7.........................................................18 May 1956 4 Sep 1969 Czech -

Neitzey, Wilfred, 61, 65, 69, SMR Dec. 1955, 3; SMR March 1956, 3; SMR

Neitzey, Wilfred, 61, 65, 69, Outbuildings furnishings cont'd. SMR Dec. 1955, 3; SMR March 1956, 4; SMR May 1956, 5; 1956, 3; SMR June 1956, 4, SMR June 1956, 6; SMR 5; SMR July 1956, 3 July 1956, 3 New York Public Library, pastry slab (marble), 28, gift of, SMR April 1956, 5 SMR Jan. 1956, 6; SMR Niepold, Mr. Frank, SMR April Feb. 1956, 7 1956, 4 Peter Collection (certain Noerr, Mr. Karl, SMR June articles), 28 1956, 1 rolling pin, 18th century, Norris, Mr. John H., 28, SMR Sept. 1956, 4 letter of praise from, 100 tea kettle, copper, 28, SMR Sept. 1956, 4 0 see also SMR Curatorial Activities for each month; Officers of the Association, Gifts; Morse, Frank E. a-c Outbuildings-- Buildings Blacksmith Shop, 70, SMR Parke-Bernet Galleries, 5, SMR Feb. 1956, 6 March 1956, 4; SMR June 1956, Butler's House, SMR Dec. 2 1955, 3, 5 Parmer, Mr. Charles, 16 Ice House, SMR Dec. 1955, Patee, Mr. & Mrs. R. W., 4 loan of silver spoons, SMR Kitchen (Family), 66, SMR Jan. 1956, 7 July 1956, 3 Pell, Mr. John, Necessaries, SMR Feb. 1956, describes restoration & opera- 6; SMR March 1956, 3 tion of Fort Ticonderoga to School House, SMR Feb. MVLA, 13, 109 1956, 6 Pepper, Hon. George Wharton, c Seed House, 67, 68, SMR Peter, Mr. Freeland, Nov. 1955, 4; SMR Dec. collection of catalogued, SMR 1955, 3; SMR Jan. 1956, May 1956, 5 5; SMR Feb. 1956, 6 collection of unpacked at MV, Slave Quarters, SMR Dec. SMR Aug. -

The Agenda of the Athenian Acropolis Museum

Zakakis, N., Bantimaroudis, P., and Zyglidopoulos, S. (2015) Museum promotion and cultural salience: the agenda of the Athenian Acropolis museum. Museum Management and Curatorship, 30(4), pp. 342-358. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/105578/ Deposited on: 1 May 2015 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Museum Promotion and Cultural Salience: The Agenda of the Athenian Acropolis Museum Nikos Zakakis Philemon Bantimaroudis Department of Cultural Technology and Communication, University of the Aegean, Mytilene, T.K. 81100, Greece E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] And Stelios Zyglidopoulos Adam Smith Business School University of Glasgow, Main Building, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, Scotland, UK E-mail: [email protected] Paper accepted for publication at the Museum Management and Curatorship As of April 2015 Museum Promotion and Cultural Salience: The Agenda of the Athenian Acropolis Museum Abstract This case study examines a process of agenda building in the context of cultural organizations. We chose the Acropolis Museum, as a new, emerging cultural organization in the European periphery which engages in public actions, in the form of symbolic initiatives, in order to set a specific cultural agenda for Greek and international media. We scrutinize seven symbolic initiatives publicized by the museum, as attributes that influence media content. We conclude that development of cultural/educational services, advertising and marketing, visitor/customer relations, partnerships, symbolic actions, special events, and supporting services constitute significant cultural attributes, which strategically become a part of the media agenda, thereby contributing toward the building of a museum agenda. -

Multilateral Agreement on Commercial Rights of Non-Scheduled Air Services in Europe Signed at Paris on 30 April 1956

MULTILATERAL AGREEMENT ON COMMERCIAL RIGHTS OF NON-SCHEDULED AIR SERVICES IN EUROPE SIGNED AT PARIS ON 30 APRIL 1956 Entry into force: In accordance with Article 6(1), the Agreement entered into force on 21 August 1957. Status: 24 parties. State Date of signature Date of deposit of Effective date Instrument of Ratification or Adherence Austria 30 October 1956 21 May 1957 21 August 1957 Belgium 30 April 1956 22 April 1960 22 July 1960 Croatia 2 July 1999 2 October 1999 Denmark 21 November 1956 12 September 1957 12 December 1957 Estonia 4 April 2001 4 July 2001 Finland 14 October 1957 6 November 1957 6 February 1958 France 30 April 1956 5 June 1957 5 September 1957 Germany 29 May 1956 11 September 1959 11 December 1959 Hungary 16 November 1993 14 February 1994 Iceland 8 November 1956 25 September 1961 25 December 1961 Ireland 29 May 1956 2 August 1961 2 November 1961 Italy 23 January 1957 Luxembourg 30 April 1956 23 December 1963 23 March 1964 Monaco 19 January 2017 19 April 2017 Netherlands (1) 12 July 1956 20 January 1958 20 April 1958 Norway 8 November 1956 5 August 1957 5 November 1957 Portugal (2) 7 May 1957 17 October 1958 17 January 1959 Republic of Moldova 23 December 1998 23 March 1999 San Marino 17 May 2016 17 August 2016 Serbia 21 March 2017 21 June 2017 Spain 8 November 1956 30 May 1957 30 August 1957 Sweden 23 January 1957 13 August 1957 13 November 1957 Switzerland 30 April 1956 2 April 1957 21 August 1957 Turkey 8 November 1956 4 November 1958 4 February 1959 United Kingdom (3) 11 January 1960 11 April 1960 The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia deposited its instrument of adherence on 23 August 2002 and became a party to the Agreement on 23 November 2002. -

Armed Forces Intervention in Post-War Turkey: a Methodological Approach of Greek Newspapers Through Political Analyses

PHOKION KOTZAGEORGIS ARMED FORCES INTERVENTION IN POST-WAR TURKEY: A METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH OF GREEK NEWSPAPERS THROUGH POLITICAL ANALYSES The Press as a political-social phenomenon may influence the forma tion of one’s conscience, make or break governments and influence public opinion in a decisive way. As an institution it may play an extremely important role in the writing of a countiy’s contemporary history. It is only recently that this last function of the Press has become the object of scientific research, resulting in the first attempts to write history using newspapers as the basic source. The present article aspires to contribute to the process of ‘deciphering’ the role played by the Press in the formulation or crystallisation of behaviours, political or other, vis-a-vis given facts or phenomena. The article aims at signposting the methodological principles in the presentation by the Greek newspapers of an external affairs event and its use by the political affairs editors of these newspapers. This article was con ceived in the course of study of the political game in Turkey as the prominence of the role of the army in that country became evident to the author. The actual cases of army intervention will not be dealt with here; what is of in terest is the reaction of the newspapers to the three military interventions in the political life of Turkey. In date order these took place on 27 May 1960, 12 March 1971 and 12 September 1980. The sources chosen are newspapers easily accessible to the public, of differing political persuasions; the time terminus of study is one month be fore and one after the date of intervention of the military. -

THE CYPRUS GREEN LINE – BRIDGING the GAP by Zachariasantoniades the Cyprus Buffer Zone Divides the Old City of Nicosia Into North and South • Abstract

Ch llenges for a new future THE CYPRUS GREEN LINE – BRIDGING GAP By Zacharias Antoniades The Cyprus buffer zone divides the old city of Nicosia into North and South • Abstract ............................... 06 • Introduction: Brief story of Nicosia ............................... 08 • "Borders are the scars of history". ............................... 14 • Lessons from Berlin ............................... 20 • Is a border purely a point of division, or can it also become one of contact between two ............................... 26 different cultures? Contents • “Third-spaces create space for envisioning ............................... 32 changes in divided cities” • The appropriate program for the appropriate ............................... 36 building. • Conclusion ............................... 42 • Bibliography ............................... 45 • Websites ............................... 47 3 4 Abstract Since 1974, Cyprus, the country that I call home has been divided in two parts, separating the two major ethnicities of the island (Greeks and Turks). In between these north and south parts lies the well-known Cyprus Buffer zone that to this day expresses the realities of the armed conflict that took place there four decades ago. This buffer zone rep- resents the lack of communication and mistrust that exists between the two ‘rival’ sides. As a Cypriot designer I felt the need to come up with an appropri- ate project that will bring people closer together, giving them the chance to communicate, debate, exchange knowledge and views and generally understand the needs of each side leading to a better and smoother social and cultural blend thus making it easier for the people to digest any future plans of total reunification. In order to get inspiration and a better understanding of how to deal with such situations I examined borders and their evolvement at differ- ent scales and contexts, but also looking at various peace-promoting projects in conflict zones. -

Machine : the Political Origins of the Greek Debt During Metapolitefsi

This is a repository copy of Fuelling the (party) machine : the political origins of the Greek debt during Metapolitefsi. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/171742/ Version: Published Version Monograph: Kammas, P., Poulima, M. and Sarantides, V. orcid.org/0000-0001-9096-4505 (2021) Fuelling the (party) machine : the political origins of the Greek debt during Metapolitefsi. Working Paper. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series, 2021002 (2021002). Department of Economics, University of Sheffield ISSN 1749-8368 © 2021 The Author(s). For reuse permissions, please contact the Author(s). Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Department Of Economics Fuelling the (party) machine: The political origins of the Greek debt during Metapolitefsi Pantelis Kammas, Maria Poulima and Vassilis Sarantides Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series SERPS no. 2021002 ISSN 1749-8368 February 2021 Fuelling the (party) machine: The political origins of the Greek debt during Metapolitefsi Pantelis Kammasa, Maria Poulimab and Vassilis Sarantidesc a Athens University of Economics and Business, Patission 76, Athens 10434, Greece. -

Olympic's Last Flight to NY

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans c v A WEEKLY GREEK AMERICAN PUBLICATION www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 12, ISSUE 625 October 3, 2009 $1.25 Farewell To Hellenism’s Home in the Air: Olympic’s Last Flight to N.Y. Tears, Anger And Disappointment Mark Final Flights to and From JFK; Future is Unclear By Stavros Marmarinos er, “It is too bad for Olympic to fin- and Theodore Kalmoukos ish this way. I hope that whichever Special to The National Herald airlines take its place, will operate at the same level as Olympic. We NEW YORK – The passengers on cared a lot about the company all the Airbus A3400-300 cried when these years; we are the first compa- the head stewardess announced on ny in the world with a perfect Monday, September 28 that the fi- record of safety. All the passengers nal Olympic flight from Athens to have been asking us for the past JFK Airport in New York had just few months about the end of landed. The sadness in her voice Olympic.” Captain Papadakos does- marked the end of an era. Olympic n’t want to work for the successor Airlines, the national air carrier of airline. He said, “It is a small com- Greece which has transported hun- pany for now, which doesn’t fulfill dreds of thousands of Greek Ameri- me, and I do not want to work cans safely for more than half a there.” On the historic final flight century back and forth from the Captain Papadakos would be ac- land of their fathers and forefa- companied by his wife Maria. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

Elements of Framing, Stereotyping and Ethnic Categorisation in the Greek Media Discourse During the 1976 Greek-Turkish Crisis

SECTION: JOURNALISM LDMD I ELEMENTS OF FRAMING, STEREOTYPING AND ETHNIC CATEGORISATION IN THE GREEK MEDIA DISCOURSE DURING THE 1976 GREEK-TURKISH CRISIS Oana-Camelia STROESCU, Researcher, PhD, “Romanian Diplomatic Institute” Abstract: The present paper details the elements contributing to the development of ethnic categorisation in the Greek daily political newspapers during the Greek-Turkish crisis of the summer of 1976. After the Cyprus operations of 1974, Greece and Turkey have lived short periods of détente and expressions of mutual sympathy, followed by tension and diplomatic and/or military posturing. The two NATO allies came often on a brink of an armed conflict due to a variety of issues linked to different interpretation of international law regarding national sovereignty in certain areas of the Aegean Sea. These states should act as lighthouses of stability in the volatile region of Eastern Mediterranean and exclude any possibility of renewed hostilities in the future, including the armed confrontation. The study analyses the position of the Greek national political dailies on the Aegean energy crisis and shows the Greek media behaviour towards the Turkish people during the 1976 crisis. What kind of nationalism is reconstructed in the Greek press discourse? Is it a kind of patriotism or do news discourse reproduce sentiments of national superiority by using framing, ethnic categorisation, stereotypes and negative images? Do they contribute to the peace process between the two countries or do they exaggerate the conflict? Our purpose is to argue that the Greek daily political press produces and promotes ethnic categorisation through textual messages for the duration of the crisis.