Geology of Dead Horse Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988

Climbs and Expeditions, 1988 The Editorial Board expresses its deep gratitude to the many people who have done so much to make this section possible. We cannot list them all here, but we should like to give particular thanks to the following: Kamal K. Guha, Harish Kapadia, Soli S. Mehta, H.C. Sarin, P.C. Katoch, Zafarullah Siddiqui, Josef Nyka, Tsunemichi Ikeda, Trevor Braham, Renato More, Mirella Tenderini. Cesar Morales Arnao, Vojslav Arko, Franci Savenc, Paul Nunn, Do@ Rotovnik, Jose Manuel Anglada, Jordi Pons, Josep Paytubi, Elmar Landes, Robert Renzler, Sadao Tambe, Annie Bertholet, Fridebert Widder, Silvia Metzeltin Buscaini. Luciano Ghigo, Zhou Zheng. Ying Dao Shui, Karchung Wangchuk, Lloyd Freese, Tom Elliot, Robert Seibert, and Colin Monteath. METERS TO FEET Unfortunately the American public seems still to be resisting the change from feet to meters. To assist readers from the more enlightened countries, where meters are universally used, we give the following conversion chart: meters feet meters feet meters feet meters feet 3300 10,827 4700 15,420 6100 20,013 7500 24,607 3400 11,155 4800 15,748 6200 20,342 7600 24,935 3500 11,483 4900 16,076 6300 20,670 7700 25,263 3600 11,811 5000 16,404 6400 20,998 7800 25,591 3700 12,139 5100 16,733 6500 21,326 7900 25,919 3800 12,467 5200 17.061 6600 21,654 8000 26,247 3900 12,795 5300 7,389 6700 21,982 8100 26,575 4000 13,124 5400 17,717 6800 22,3 10 8200 26,903 4100 13,452 5500 8,045 6900 22,638 8300 27,231 4200 13,780 5600 8,373 7000 22,966 8400 27,560 4300 14,108 5700 8,701 7100 23,294 8500 27,888 4400 14,436 5800 19,029 7200 23,622 8600 28,216 4500 14,764 5900 9,357 7300 23,951 8700 28,544 4600 15,092 6000 19,685 7400 24,279 8800 28,872 NOTE: All dates in this section refer to 1988 unless otherwise stated. -

Thesis-Reproduction (Electronic)

A synopsis of the geologic and structural history of the Randsburg Mining District Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Morehouse, Jeffrey Allen, 1953-1985 Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 08:53:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/558085 Call No. BINDING INSTRUCTIONS INTERUBRARY INSTRUCTIONS Dept. E9791 Author: Morehouse, J. 1988 245 Title: RUSH___________________ PERMABIND____________ PAMPHLET._____________ GIFT____________________ COLOR: M,S* POCKET FOR MAP______ COVERS Front_______Both Special Instructions - Bindery or Repair REFERENCE____ i________ O th er--------------------------- 3 /2 /9 0 A SYNOPSIS OF THE GEOLOGIC AND STRUCTURAL HISTORY OF THE RANDSBURG MINING DISTRICT by Jeffrey Allen Morehouse A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 8 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA TUCSON, ARIZONA 85721 DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES BUILDING *77 GOULD-SIMPSON BUILDING TEL (602) 621-6024 To the reader of Jeff Morehouse's thesis: Jeff Morehouse's life was lamentably cut short by a hiking-rock climbing accident in the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson, Arizona, on March 24, 1985. Those who knew Jeff will always regret that accident, not only because it abbreviated what would certainly have been an uncommonly productive geological career but also because it snuffed an effervescent, optimistic,, charming personality. -

Development of a Dilatant Damage Zone Along a Thrust Relay in a Low-Porosity Quartz Arenite

Journal of Structural Geology 28 (2006) 776–792 www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Development of a dilatant damage zone along a thrust relay in a low-porosity quartz arenite Jennie E. Cook a, William M. Dunne a,*, Charles M. Onasch b a Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996-1410, USA b Department of Geology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403, USA Received 12 August 2005; received in revised form 26 January 2006; accepted 15 February 2006 Available online 18 April 2006 Abstract A damage zone along a backthrust fault system in well-cemented quartz arenite in the Alleghanian foreland thrust system consists of a network of NW-dipping thrusts that are linked by multiple higher-order faults and bound a zone of intense extensional fractures and breccias. The damage zone developed at an extensional step-over between two independent, laterally propagating backthrusts. The zone is unusual because it preserves porous brittle fabrics despite formation at O5 km depth. The presence of pervasive, late-stage fault-normal joints in a fault-bounded horse in the northwestern damage zone indicates formation between two near-frictionless faults. This decrease in frictional resistance was likely a result of increased fluid pressure. In addition to physical effects, chemical effects of fluid also influenced damage zone development. Quartz cements, fluid inclusion data, and Fourier Transform Infrared analysis indicate that both aqueous and methane-rich fluids were present within the damage zone at different times. The backthrust network likely acted as a fluid conduit system, bringing methane-rich fluids up from the underlying unit and displacing resident aqueous fluids. -

A N–S-Trending Active Extensional Structure, the Fiuhut (Afyon) Graben

Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences (Turkish J. Earth Sci.), Vol. 16, 2007, pp. 391–416. Copyright ©TÜB‹TAK A N–S-trending Active Extensional Structure, the fiuhut (Afyon) Graben: Commencement Age of the Extensional Neotectonic Period in the Isparta Angle, SW Turkey AL‹ KOÇY‹⁄‹T & fiULE DEVEC‹ Middle East Technical University, Department of Geological Engineering, Active Tectonics and Earthquake Research Laboratory, TR–06531 Ankara, Turkey (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The fiuhut graben is an 8–11-km-wide, 24-km-long, N–S-trending, active extensional structure located on the southern shoulder of the Akflehir-Afyon graben, near the apex of the outer Isparta Angle. The fiuhut graben developed on a pre-Upper Pliocene rock assemblage comprising pre-Jurassic metamorphic rocks, Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous platform carbonates, the Lower Miocene–Middle Pliocene Afyon stratovolcanic complex and a fluvio- lacustrine volcano-sedimentary sequence. The eastern margin of the fiuhut graben is dominated by the Afyon volcanics and their well-bedded fluvio- lacustrine sedimentary cover, which is folded into a series of NNE-trending anticlines and synclines. This volcano- sedimentary sequence was deformed during a phase of WNW–ESE contraction, and is overlain with angular unconformity by nearly horizontal Plio–Quaternary graben infill. Palaeostress analyses of slip-plane data recorded in the lowest unit of the modern graben infill and on the marginal active faults indicate that the fiuhut graben has been developing as a result of ENE–WSW extension since the latest Pliocene. The extensional neotectonic period in the Isparta Angle started in the latest Pliocene. All margins of the fiuhut graben are determined and controlled by a series of oblique-slip normal fault sets and isolated fault segments. -

Faults and Joints

97 FAULTS Fractures are planar discontinuities, i.e. interruption of the rock physical continuity, due to stresses. The geological fractures occur at every scale so that any large volume of rock has some or many. These discontinuities are attributed to sudden relaxation of elastic energy stored in the rock. The geological fractures have their economic importance. The loss of continuity in intact rocks provides the necessary permeability for migration and accumulation of fluids such as groundwater and petrol. Fractured reservoirs and aquifers are typically anisotropic since their transmissivity is regulated by the conductive properties of fractures, which the local stress field partially controls. Geological fractures may be partially or wholly healed by the introduction of secondary minerals, often giving rise to ore deposits, or by recrystallization of the original minerals. Planar discontinuities along which rocks lose cohesion during their brittle behavior are: - joints if there is no component of displacement parallel to the plane (there may be some very small orthogonal parting; joints are extension fractures). - faults if rocks on both sides of the plane have moved relative to each other, parallel to the plane (faults are shear fractures). - veins if the fractures are filled with secondary crystallization. Joints and faults divide the rocks into blocks whose size and shape must be taken into consideration for engineering, quarrying, mining, and geomorphology. Fault terminology Definitions Faults separate two adjacent blocks of rock that have moved past each other because of induced stresses. The notion of localized movement leads to two genetically different classes of faults reflecting the two basic behaviors of rocks under stress: brittle and ductile. -

Geology Maps

Student Name: Grade: Physical Geology 101 Laboratory Interpreting Geology Maps Introduction & Purpose: The purpose of this laboratory is to gain a working knowledge and skill to read geology maps. Students will learn to read a geology map for the purpose of understanding surface and subsurface structural relations and geologic history that may include a record of rock forming events, mountain building deformation, and the relationship between geology and topography Part I. Review Taking Strike and Dip Directions: Use the Compass and Inclinometer, provided by your instructor, to determine the strike and dip of two inclined boards that are setup in the classroom. Note: Use the boards labeled “X” and “Z”. 1. What is the strike and dip of the board labeled “X” strike: ___________ dip: ________ 2. What is the strike and dip of the board labeled “Z” strike: ___________ dip: ________ Part II – Reading and Interpreting a Simplified Geologic Map Introduction: A geologic map is a greatly scaled-down, two-dimensional abstract representation of the surface geology, structure, and relief of a geographic region of Earth, or even another terrestrial planet. A geologic map typically includes most information found on a topographic map, but most importantly, includes color-coding regions and symbols that denote rock units, contacts, and other structural information. Additionally, all the geologic color-coding and symbols are explained in the legend on a geologic map, including topographic and cardinal information. Directions: The simplified geology map below contains several geologic features that include the following: Sedimentary beds "A", "B", "C", and "D"; Basalt dike" E"; Granite pluton; Fault "Y"; and Unconformity "Z". -

Mineral Resources of the Horse Mountain and Continental Divide Wilderness Study Areas, Catron County, New Mexico

Mineral Resources of the Horse Mountain and Continental Divide Wilderness Study Areas, Catron County, New Mexico U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1734-C 4: Chapter C Mineral Resources of the Horse Mountain and Continental Divide Wilderness Study Areas, Catron County, New Mexico By JAMES C. RATTE, RICHARD W. SALTUS, and ROBERT L TURNER U.S. Geological Survey CARL L ALMQUIST and ROBERT H. WOOD, 2d U.S. Bureau of Mines U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1734 MINERAL RESOURCES OF WILDERNESS STUDY AREAS- WEST-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1988 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section U.S. Geological Survey Federal Center Box 25425 Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mineral resources of the Horse Mountain and Continental Divide Wilderness Study Areas, Catron County, New Mexico. (Mineral resources of wilderness study areas west-central New Mexico ; ch. C) (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 1734-C) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.3:1734-C 1. Mines and mineral resources New Mexico Horse Mountain Wilderness. 2. Mines and mineral resources New Mexico Continental Divide Wilderness. 3. Horse Mountain Wilderness (N.M.) 4. Continental Divide Wilderness (N.M.) I. Ratte, James C. (James Clifford), 1925- . II. Series. QE75.B9 no. 1734-C 557.3 S [553'.09789'93] 87-600410 [TN24.N6] STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Areas The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (Public Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires the U.S. -

Journal of Mechanics of Materials and Structures Vol 1 Issue 2, Feb 2006

JOURNAL OF MECHANICS OF MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES Journal of Mechanics of Materials and Structures Volume 1 No. 2 February 2006 Journal of Mechanics of Materials and Structures 2006 Vol. 1, No. 2 Volume 1, Nº 2 February 2006 mathematical sciences publishers JOURNAL OF MECHANICS OF MATERIALS AND STRUCTURES http://www.jomms.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles R. Steele ASSOCIATE EDITOR Marie-Louise Steele Division of Mechanics and Computation Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 USA SENIOR CONSULTING EDITOR Georg Herrmann Ortstrasse 7 CH–7270 Davos Platz Switzerland BOARD OF EDITORS D. BIGONI University of Trento, Italy H. D. BUI Ecole´ Polytechnique, France J. P. CARTER University of Sydney, Australia R. M. CHRISTENSEN Stanford University, U.S.A. G. M. L. GLADWELL University of Waterloo, Canada D. H. HODGES Georgia Institute of Technology, U.S.A. J. HUTCHINSON Harvard University, U.S.A. C. HWU National Cheng Kung University, R.O. China IWONA JASIUK University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign B. L. KARIHALOO University of Wales, U.K. Y. Y. KIM Seoul National University, Republic of Korea Z. MROZ Academy of Science, Poland D. PAMPLONA Universidade Catolica´ do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil M. B. RUBIN Technion, Haifa, Israel Y. SHINDO Tohoku University, Japan A. N. SHUPIKOV Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Ukraine T. TARNAI University Budapest, Hungary F. Y. M. WAN University of California, Irvine, U.S.A. P. WRIGGERS Universitat¨ Hannover, Germany W. YANG Tsinghua University, P.R. China F. ZIEGLER Tech Universitat¨ Wien, Austria PRODUCTION PAULO NEY DE SOUZA Production Manager SILVIO LEVY Senior Production Editor NICHOLAS JACKSON Production Editor ©Copyright 2007. -

Quicksilver Deposits of the Horse Heaven Mining District Oregon

Quicksilver Deposits of the Horse Heaven Mining District Oregon GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 969-E QUICKSILVER DEPOSITS OF THE HORSE HEAVEN MINING DISTRICT, OREGON By A. C. WATERS, RANDALL E. BROWN, ROBERT R. COMPTON, LLOYD W. STAPLES, GEORGE W. WALKER, and HOWEL WILLIAMS ABSTRACT Commercial quantities of cinnabar were discovered in the Horse Heaven dis trict, north-central Oregon, in 1933. The district has since produced' 15,000 flasks of quicksilver, most of which has come from the Horse Heaven mine, although the Axe Handle mine produced about 150 flasks. Four prospects contain some cinnabar that may be mined for quicksilver in the future. The ore deposits found thus far are closely related to volcanic plugs. Four of them occur in or near autobrecciated plugs of biotite rhyolite. The ores of the Axe Handle mine are in altered rocks at tho margin of a plug of augite andesite. A small outlier of pre-Tertiary metamorphic rocks occurs about 5 miles north of the Horse Heaven mine. The oldest rocks close to the mine, however, are andesite flows, tuffs, and tuffaceous sedimentary rocks of the Clarno formation. The Clarno rocks were deformed, eroded to a rolling surf ace, and then covered! by three series of volcanic rocks. The oldest consists of basaltic andesite, fol lowed after a period of erosion by biotite rhyolite flows and pyroclastics, It is in the rhyolite plugs formed during this period of volcanism that most of the quicksilver deposits are found. Finally, the rhyolite flows and tuffs were moderately eroded, and in the southern part of the area they were covered by flows of augite andesite. -

Glossary of Thrust Tectonics Terms

Glossary of thrust tectonics terms K.R. McClay Department of Geology, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, University of London, Egham, Surrey, England, TW20 OEX This glossary aims to illustrate, and to define where possible, recognise the difficulty in precisely defining many of the some of the more widely used terms in thrust tectonics. It is terms used in thrust tectonics as individual usages and pref presented on a thematic basis - individual thrust faults and erences vary widely. related structures, thrust systems, thrust fault related folds, 3- D thrust geometries, thrust sequences, models of thrust sys tems, and thrusts in inversion tectonics. Fundamental terms Thrust faults are defined first, followed by an alphabetical listing of related structures. Where appropriate key references are given. Thrust fault: A contraction fault that shortens a datum surface, usually bedding in upper crustal rocks or a regional Since some of the best studied thrust terranes such as the foliation surface in more highly metamorphosed rocks. Canadian Rocky Mountains, the Appalachians, the Pyrenees, and the Moine thrust zone are relatively high level foreland This section of the glossary defines terms applied to indi fold and thrust belts it is inevitable that much of thrust vidual thrust faults (after McClay 1981; Butler 1982; Boyer tectonics terminology is concerned with structures found in & Elliott 1982; Diegel 1986). the external zones of these belts. These thrustbelts character istically consist of platform sediments deformed by thrust Backthrust: A thrust fault which has an opposite vergence faults which have a ramp-flat trajectories (Bally et al. 1966; to that of the main thrust system or thrust belt (Fig. -

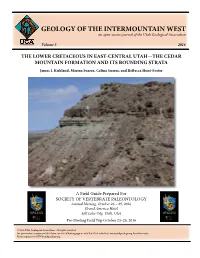

THE LOWER CRETACEOUS in EAST-CENTRAL UTAH—THE CEDAR MOUNTAIN FORMATION and ITS BOUNDING STRATA James I

GEOLOGY OF THE INTERMOUNTAIN WEST an open-access journal of the Utah Geological Association Volume 3 2016 THE LOWER CRETACEOUS IN EAST-CENTRAL UTAH—THE CEDAR MOUNTAIN FORMATION AND ITS BOUNDING STRATA James I. Kirkland, Marina Suarez, Celina Suarez, and ReBecca Hunt-Foster A Field Guide Prepared For SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY Annual Meeting, October 26 – 29, 2016 Grand America Hotel Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Pre-Meeting Field Trip October 23–25, 2016 © 2016 Utah Geological Association. All rights reserved. For permission to copy and distribute, see the following page or visit the UGA website at www.utahgeology.org for information. Email inquiries to [email protected]. GEOLOGY OF THE INTERMOUNTAIN WEST an open-access journal of the Utah Geological Association Volume 3 2016 Editors UGA Board Douglas A. Sprinkel Thomas C. Chidsey, Jr. 2016 President Bill Loughlin [email protected] 435.649.4005 Utah Geological Survey Utah Geological Survey 2016 President-Elect Paul Inkenbrandt [email protected] 801.537.3361 801.391.1977 801.537.3364 2016 Program Chair Andrew Rupke [email protected] 801.537.3366 [email protected] [email protected] 2016 Treasurer Robert Ressetar [email protected] 801.949.3312 2016 Secretary Tom Nicolaysen [email protected] 801.538.5360 Bart J. Kowallis Steven Schamel 2016 Past-President Jason Blake [email protected] 435.658.3423 Brigham Young University GeoX Consulting, Inc. 801.422.2467 801.583-1146 UGA Committees [email protected] [email protected] Education/Scholarship Loren Morton -

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Canyonlands National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Canyonlands National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2005/003 Canyonlands National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2005/003 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 September 2005 U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. Views and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect policies of the National Park Service. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service.