The Abstraction of Meaning in the Digital Landscape and the Communities That Form There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Pepe the Frog

PEPE THE FROG: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies by BEN PETTIS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Spring 2018 An Abstract of the Thesis of Ben Pettis for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken Spring 2018 Title: Pepe the Frog: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and Its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies Approved: _______________________________________ Dr. Peter Alilunas This thesis examines Internet memes, a unique medium that has the capability to easily and seamlessly transfer ideologies between groups. It argues that these media can potentially enable subcultures to challenge, and possibly overthrow, hegemonic power structures that maintain the dominance of a mainstream culture. I trace the meme from its creation by Matt Furie in 2005 to its appearance in the 2016 US Presidential Election and examine how its meaning has changed throughout its history. I define the difference between a meme instance and the meme as a whole, and conclude that the meaning of the overall meme is formed by the sum of its numerous meme instances. This structure is unique to the medium of Internet memes and is what enables subcultures to use them to easily transfer ideologies in order to challenge the hegemony of dominant cultures. Dick Hebdige provides a model by which a dominant culture can reclaim the images and symbols used by a subculture through the process of commodification. -

POPULAR SOCIAL MEDIA SITES Below Is a List of Some of the Most Commonly Used Youth and Teen Social Networking Sites and Tools

POPULAR SOCIAL MEDIA SITES Below is a list of some of the most commonly used youth and teen social networking sites and tools. Ask.fm (http://ask.fm) Participants log on, post a question anonymously and anyone may answer anonymously. “Do you think I am fat?” or “Would you date me?” are examples of questions posted in the past. There have also been examples in which individuals were encouraged to kill themselves. The site has courted controversy by not having workable reporting, tracking or parental control processes, which have become the norm on other social media websites. Twitter (https://twitter.com) An online social networking and microblogging service that enables users to send and read "tweets", which are text messages limited to 140 characters. Instagram (http://instagram.com) A photo-sharing app for iPhone. Kik (http://kik.com) Kik is as an alternative to email or text messaging and its popularity has grown in the last two years. Kik is accessible on smartphones and supports over 4 million users, called “Kicksters.” Users are not restricted to sending text messages with Kik. Images, videos, sketches, emoticions and more may be sent. A user can block users on Kik from contacting them. Wanelo (http://wanelo.com) Wanelo (from Want, Need, Love) sells unique products online, all posted by users. Products posted for sale range from dishes, clothing, intimate wear and other potentially “R-Rated” products. Vine (https://vine.co) Vine is used to create and share free and instant six-second videos. Topic and content ranges. Snapchat (http://www.snapchat.com) A photo messaging application. -

On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities In

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19 Fatemeh Tahmasbi Leonard Schild Chen Ling Binghamton University CISPA Boston University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn Gianluca Stringhini Yang Zhang Binghamton University Boston University CISPA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savvas Zannettou Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in COVID-19, Sinophobia, Hate Speech, Twitter, 4chan unprecedented ways. In the face of the projected catastrophic conse- ACM Reference Format: quences, most countries have enacted social distancing measures in Fatemeh Tahmasbi, Leonard Schild, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. Under these conditions, Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2021. “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: the Web has become an indispensable medium for information ac- On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the quisition, communication, and entertainment. At the same time, Face of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), unfortunately, the Web is being exploited for the dissemination April 19–23, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. of potentially harmful and disturbing content, such as the spread https://doi.org/10.1145/3442381.3450024 of conspiracy theories and hateful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards Chinese people and people of Asian 1 INTRODUCTION descent since COVID-19 is believed to have originated from China. -

A Discourse Analysis on Humor Used in 9Gag Posts on Instagram

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS ON HUMOR USED IN 9GAG POSTS ON INSTAGRAM THESIS BY : ELZA OKTAVIANA NIM 14320011 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS ON HUMOR USED IN 9GAG POSTS ON INSTAGRAM THESIS Present to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim, Malang in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) Composed By: Elza Oktaviana NIM 14320011 Advisor: Marokhin, M.A NIDT 19780410201608011035 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 i APPROVAL OF SHEET This is to clarify that Elza Oktaviana‟s thesis entitled A Discourse Analysis on Humor Used in 9gag Post on Instagram has been approved by thesis advisor for further approval by the the Board of Examiners. Malang, May 22th, 2018 Approved by Acknowledged by The Advisor, The Head of English Letters Department, Masrokhin, M.A. Rina Sari, M. Pd. NIDT 19780410201608011035 NIP 19750610 200604 2 002 The Dean of Faculty of Humanities Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim, Malang Dr. Hj. Syafiyah, M.A. NIP 19660910 1991032 002 ii LEGITIMATION SHEET This is to clarify that Elza Oktaviana‟s thesis entitled A Discourse Analysis on Humor Used in 9gag Post on Instagram has been approved by the Board of Examiners as the requirement for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S). Malang, June 7th, 2018 The Board of Examiner Signatures 1. Dr. Hj. Galuh Nur Rohmah, M. Pd, M. Ed.(Examiner) NIP 19740211 199803 2 002 2. Dr. Hj. Syafiyah, M.A. (Chairman) NIP 19660910 1991032 002 3. -

An Analysis of Factors Influencing Transmission of Internet Memes of English-Speaking Origin in Chinese Online Communities

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 969-977, September 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0805.19 An Analysis of Factors Influencing Transmission of Internet Memes of English-speaking Origin in Chinese Online Communities Siyue Yang Shanxi Normal University, Linfen, China Abstract—Meme, as defined in Dawkins' 1976 book 'The Selfish Gene', is "an idea, behaviour or style that spreads from person to person within a culture". Internet meme is an extension of meme, with the defining characteristic being its spread via Internet. While online communities of all cultures generate their own memes, owing to the colossal amount of content in English and the long & widespread adoption of Internet across all strata of society in English-speaking countries, the vast majority of high-impact and well-documented memes have their origin in English-speaking communities. In addition to their spread in the original culture sphere, some of these prominent memes have also crossed the cultural boundaries and entered the parlance of Chinese Internet communities. This paper seeks to give a brief introduction to Internet memes in general, and explore the factors that control and/or facilitate a meme’s ability to enter Chinese communities. Index Terms—Internet meme, cross-cultural communication, Chinese Internet I. INTRODUCTION Internet meme, an extension of the term "meme" first coined by Richard Dawkins (1976) in his work The Selfish Gene (p. 192), refers to the unique form of meme that spreads through the Internet. Internet memes in their various forms currently enjoy substantial popularity among Internet users all around the globe, and are flourishing and becoming increasingly entrenched in the mainstream culture of all the disparate societies in this connected world. -

Redalyc.Defining and Characterizing the Concept of Internet Meme

CES Psicología E-ISSN: 2011-3080 [email protected] Universidad CES Colombia Castaño Díaz, Carlos Mauricio Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme CES Psicología, vol. 6, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2013, pp. 82-104 Universidad CES Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=423539422007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista CES Psicología ISSN 2011-3080 Volumen 6 Número 1 Enero-Junio 2013 pp. 82-104 Artículo de investigación Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme Definición y caracterización del concepto de Meme de Internet Carlos Mauricio Castaño Díaz1 University of Copenhagen, Dinamarca. Forma de citar: Castaño, D., C.M. (2013). Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme. Revista CES Psicología, 6(2),82-104.. Abstract The research aims to create a formal definition of “Internet Meme” (IM) that can be used to characterize and study IMs in academic contexts such as social, communication sciences and humanities. Different perspectives of the term meme were critically analysed and contrasted, creating a contemporary concept that synthesizes different meme theorists’ visions about the term. Two different kinds of meme were found in the contemporary definitions, the meme-gene, and the meme- virus. The meme-virus definition and characteristics were merged with definitions of IM taken from the Internet in the light of communication theories, in order to develop a formal characterization of the concept. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

Describing Doggo-Speak: Features of Doggo Meme Language

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Describing Doggo-Speak: Features of Doggo Meme Language Jennifer Bivens The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2718 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DESCRIBING DOGGO-SPEAK: FEATURES OF DOGGO MEME LANGUAGE by JENNIFER BIVENS A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Jennifer Bivens All Rights Reserved ii Describing Doggo-Speak: Features of Doggo Meme Language by Jennifer Bivens This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date William Sakas Thesis Advisor Date Gita Martohardjono Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Describing Doggo-Speak: Features of Doggo Meme Language by Jennifer Bivens Advisor: William Sakas Doggo-speak is a specialized way of writing most commonly associated with captions on Doggo memes, humorous images of dogs shared in online communities. This paper will explore linguistic features of Doggo-speak through analysis of social media posts by Doggo fan pages. It will use the discussed features as inputs to five machine learning classifiers and will show, through this classification task, that the discussed features are sufficient for distinguishing between Doggo- speak and more general English text. -

Hypersphere Anonymous

Hypersphere Anonymous This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-1-329-78152-8 First edition: December 2015 Fourth edition Part 1 Slice of Life Adventures in The Hypersphere 2 The Hypersphere is a big fucking place, kid. Imagine the biggest pile of dung you can take and then double-- no, triple that shit and you s t i l l h a v e n ’ t c o m e c l o s e t o o n e octingentillionth of a Hypersphere cornerstone. Hell, you probably don’t even know what the Hypersphere is, you goddamn fucking idiot kid. I bet you don’t know the first goddamn thing about the Hypersphere. If you were paying attention, you would have gathered that it’s a big fucking 3 place, but one thing I bet you didn’t know about the Hypersphere is that it is filled with fucked up freaks. There are normal people too, but they just aren’t as interesting as the freaks. Are you a freak, kid? Some sort of fucking Hypersphere psycho? What the fuck are you even doing here? Get the fuck out of my face you fucking deviant. So there I was, chilling out in the Hypersphere. I’d spent the vast majority of my life there, in fact. It did contain everything in my observable universe, so it was pretty hard to leave, honestly. At the time, I was stressing the fuck out about a fight I had gotten in earlier. I’d been shooting some hoops when some no-good shithouses had waltzed up to me and tried to make a scene. -

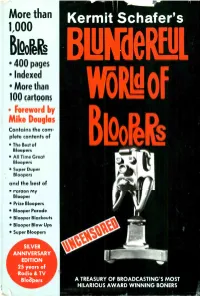

Blunderful-World-Of-Bloopers.Pdf

o More than Kermit Schafer's 1,000 BEQ01416. BLlfdel 400 pages Indexed More than 100 cartoons WÖLof Foreword by Mike Douglas Contains the com- plete contents of The Best of Boo Ittli Bloopers All Time Great Bloopers Super Duper Bloopers and the best of Pardon My Blooper Prize Bloopers Blooper Parade Blooper Blackouts Blooper Blow Ups Super Bloopers SILVER ANNIVERSARY EDITION 25 years of Radio & TV Bloópers A TREASURY OF BROADCASTING'S MOST HILARIOUS AWARD WINNING BONERS Kermit Schafer, the international authority on lip -slip- pers, is a veteran New York radio, TV, film and recording Producer Kermit producer. Several Schafer presents his Blooper record al- Bloopy Award, the sym- bums and books bol of human error in have been best- broadcasting. sellers. His other Blooper projects include "Blooperama," a night club and lecture show featuring audio and video tape and film; TV specials; a full - length "Pardon My Blooper" movie and "The Blooper Game" a TV quiz program. His forthcoming autobiography is entitled "I Never Make Misteaks." Another Schafer project is the establish- ment of a Blooper Hall of Fame. In between his many trips to England, where he has in- troduced his Blooper works, he lectures on college campuses. Also formed is the Blooper Snooper Club, where members who submit Bloopers be- come eligible for prizes. Fans who wish club information or would like to submit material can write to: Kermit Schafer Blooper Enterprises Inc. Box 43 -1925 South Miami, Florida 33143 (Left) Producer Kermit on My Blooper" movie opening. (Right) The million -seller gold Blooper record.