Towards the Sanctuarisation of Events in Public Space? Festive Events and Protests in Brussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

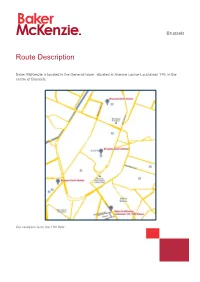

Brussels Aterloose Charleroisestwg

E40 B R20 . Leuvensesteenweg Ninoofsestwg acqmainlaan J D E40 E. oningsstr K Wetstraat E19 an C ark v Belliardstraat Anspachlaan P Brussel Jubelpark Troonstraat Waterloolaan Veeartsenstraat Louizalaan W R20 aversestwg. T Kroonlaan T. V erhaegenstr Livornostraat . W Louizalaan Brussels aterloose Charleroisestwg. steenweg Gen. Louizalaan 99 Avenue Louise Jacqueslaan 1050 Brussels Alsembergsesteenweg Parking: Brugmannlaan Livornostraat 14 Rue de Livourne A 1050 Brussels E19 +32 2 543 31 00 A From Mons/Bergen, Halle or Charleroi D From Leuven or Liège (Brussels South Airport) • Driving from Leuven on the E40 motorway, go straight ahead • Driving from Mons on the E19 motorway, take exit 18 of the towards Brussels, follow the signs for Centre / Institutions Brussels Ring, in the direction of Drogenbos / Uccle. européennes, take the tunnel, and go straight ahead until you • Continue straight ahead for about 4.5 km, following the tramway reach the Schuman roundabout. (the name of the road changes : Rue Prolongée de Stalle, Rue de • Take the 2nd road on the right to Rue de la Loi. Stalle, Avenue Brugmann, Chaussée de Charleroi). • Continue straight on until you cross the Small Ring / Boulevard du • About 250 metres before Place Stéphanie there are traffic lights: at Régent. Turn left and take the small Ring (tunnels). this crossing, turn right into Rue Berckmans. At the next crossing, • See E turn right into Rue de Livourne. • The entrance to the car park is at number 14, 25 m on the left. E Continue • Follow the tunnels and drive towards La Cambre / Ter Kameren B From Ghent (to the right) in the tunnel just after the Louise exit. -

ACCOMMODATION Abroad Student

ACCOMMODATION FOR ABROAD STUDENT At the Brussels School of Governance, a number of different housing opFons are available for incoming study abroad students: Homestay/Host Family If you are looKing to immerse yourself in the lifestyle of a Belgian and improve your French or Dutch, then staying in a host family is the ideal opFon for you! All our host families live close to university and speaK English. What does the homestay include? Bed and breakfast, 7 days a week (includes sheets and towels) Dinner 4 days a week (weekdays) How much does it cost? €165 per weeK. Personalised Assistance Housing The Brussels School of Governance Housing Coordinator offers personalised assistance to students in locaFng and leasing a student flat or a room. The service includes the placement in housing and personal assistance to help students understand the specific aspects (both culturally and legally) that they may encounter prior to arrival or during their stay. The contract can be reviewed by the Housing Coordinator before signature and possibly a template in English proposed to the landlord for signature with our students. Partner Residence If you are looKing for a dorm style feel, at a 10-minute walK from campus, you are welcome to stay at our School’s partner’s residence: 365 Rooms. The Brussels School of Governance is the alliance between the Ins7tute for European Studies and Vesalius College. Page 1 of 14 At 365 you can have your own room while being surrounded by other Belgian and internaonal students. This accommodaFon offers 2 different room styles: • Small, middle-sized or large studio, with en-suite bathroom and small kitchenebe • Single room with shared bathroom and Kitchen. -

Brussels 1 Brussels

Brussels 1 Brussels Brussels • Bruxelles • Brussel — Region of Belgium — • Brussels-Capital Region • Région de Bruxelles-Capitale • Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest A collage with several views of Brussels, Top: View of the Northern Quarter business district, 2nd left: Floral carpet event in the Grand Place, 2nd right: Brussels City Hall and Mont des Arts area, 3rd: Cinquantenaire Park, 4th left: Manneken Pis, 4th middle: St. Michael and St. Gudula Cathedral, 4th right: Congress Column, Bottom: Royal Palace of Brussels Flag Emblem [1] [2][3] Nickname(s): Capital of Europe Comic city Brussels 2 Location of Brussels(red) – in the European Union(brown & light brown) – in Belgium(brown) Coordinates: 50°51′0″N 4°21′0″E Country Belgium Settled c. 580 Founded 979 Region 18 June 1989 Municipalities Government • Minister-President Charles Picqué (2004–) • Governor Jean Clément (acting) (2010–) • Parl. President Eric Tomas Area • Region 161.38 km2 (62.2 sq mi) Elevation 13 m (43 ft) [4] Population (1 January 2011) • Region 1,119,088 • Density 7,025/km2 (16,857/sq mi) • Metro 1,830,000 Time zone CET (UTC+1) • Summer (DST) CEST (UTC+2) ISO 3166 BE-BRU [5] Website www.brussels.irisnet.be Brussels (French: Bruxelles, [bʁysɛl] ( listen); Dutch: Brussel, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫ] ( listen)), officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region[6][7] (French: Région de Bruxelles-Capitale, [ʁe'ʒjɔ̃ də bʁy'sɛlkapi'tal] ( listen), Dutch: Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫs ɦoːft'steːdələk xəʋɛst] ( listen)), is the capital -

19 Keer Brussel 19 Fois Bruxelles 19 Times Brussels

19 keer Brussel 19 fois Bruxelles 19 times Brussels Brusselse Thema’s Thèmes Bruxellois Brussels Themes 7 Els Witte en Ann Mares (red.) 19 keer Brussel 19 fois Bruxelles 19 times Brussels Brusselse Thema’s Thèmes Bruxellois Brussels Themes 7 VUBPRESS met de steun van de FWO-Wetenschappelijke Onderzoeksgemeenschap avec l’appui du Réseau de Recherche Scientifique du FWO with support of the Scientific Research Network of the FWO Omslagontwerp: Danny Somers Boekverzorging: Boudewijn Bardyn © 2001 VUBPRESS Waversesteenweg 1077, 1160 Brussel Fax: ++ 32 2 629 26 94 ISBN 90 5487 292 6 NUGI 641 D / 2001 / 1885 / 006 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Inhoudstafel Table des matières Content Een nieuwe fase in het onderzoek naar Brussel en andere meertalige (hoofd)steden: de totstandkoming van een wetenschappelijke onderzoeksgemeenschap …………………………… 11 Une nouvelle phase dans la recherche sur Bruxelles et d’autres villes (capitales) multilingues: la réalisation d’un Réseau de Recherche Scientifique …………………………………… 21 New Developments in Research on Brussels and other Multilingual (Capital) Cities: the Creation of a Scientific Research Network ……… 31 Els Witte TAALSOCIOLOGISCHE EN SOCIOLINGUÏSTISCHE ASPECTEN …………………… 41 ASPECTS SOCIO-LINGUISTIQUES | SOCIO-LINGUISTIC ASPECTS Over Brusselse Vlamingen en het Nederlands in Brussel ……………… 43 A propos des Bruxellois flamands et du néerlandais à Bruxelles ……… 82 Flemish residents and the Dutch language in Brussels ………………… 83 Rudi Janssens A propos du sens de l’expression ‘parler bruxellois’ ……………………… 85 Over de betekenis van de uitdrukking ‘Brussels spreken’ …………… 101 On the meaning of the expression ‘to speak Brussels’ ………………… 102 Sera De Vriendt Ethnic composition and language distribution in social networks of immigrant speakers. -

List of Partners Anderlecht Auderghem Bruxelles Centre Etterbeek Forest

List of partners Anderlecht Bibliothèque locale communale d'Anderlecht (1-7 Rue du Chapelain, 1070 Anderlecht) Openbare Bibliotheek Anderlecht (Rue Saint-Guidon 97, 1070 Anderlecht) Circularium (Chaussée de Mons 95, 1070 Anderlecht) Escale du Nord - Centre culturel d'Anderlecht (Rue du Chapelain 1, 1070 Anderlecht) KDV de Zonnebloem (Avenue Paul Janson 68, 1070 Anderlecht) Werkplaats Walter (Rue Van Lint 43, 1070 Anderlecht) Auderghem Rouge-Cloître (Rue du Rouge-Cloître 4, 1160 Auderghem) Parc Seny (Vorstlaan, 1160 Auderghem) Parc du Bergoje (Rue Jacques Bassem 1160 Auderghem) Bibliothèque de Centre (Boulevard du Souverain 187, 1160 Auderghem) Parc Tenreuken (Boulevard du Souverain, 1160 Auderghem) Bruxelles centre Piola Libri (Rue Franklin 66/68, 1000 Bruxelles) Punto y Coma (Rue Stevin 115A, 1000 Bruxelles) Tulitu (Rue de Flandre 55, 1000 Bruxelles) Wasterstones (Boulevard Adolphe Max 71/75, 1000 Bruxelles) De Markten (Rue du Vieux Marché aux Grains 5, 1000 Bruxelles Espace Magh (Rue du Poinçon 17, 1000 Bruxelles) PointCulture Bruxelles (Rue royale 145, 1000 Bruxelles) Théâtre des martyrs (Place de Martyrs 22, 1000 Bruxelles) Etterbeek Bibliothèque Communale Hergé (Avenue de la Chasse 211, 1040 Etterbeek) Gemeentelijke Openbare Bibliotheek Etterbeek (Avenue d'Auderghem 191, 1040 Etterbeek) Espace Senghor (Chaussée de Wavre 366, 1040 Etterbeek) Gemeenschap centrum (De Maelbeek) (Rue du Cornet 97, 1040 Etterbeek) Forest ABŸ (Abbaye de Forest) BRASS (Avenue Van Volxem 364, 1190 Forest) Gemeenschap centrum Ten Weyngaert (Rue des Alliés -

The #1Bru1vote Manifesto Call for the Right to Vote in Brussels-‐Capital R

The #1bru1Vote Manifesto Also petition text Call for the right to vote in Brussels-Capital Region elections for all Brussels residents “One Brusseleir One Vote!” On 26 May 2019, as the Brussels-Capital Region celebrates its 30 years of existence, citizens of Brussels-Capital will vote to elect the assembly of this city-region – the Brussels-Capital Parliament. But not all residents of Brussels, or Brusseleirs, will be able to vote! 1 in 3 Brussels-Capital residents – or 415,000 people – are denied the right to vote, and are prevented from taking an active political role, because they are non-Belgian. These 280,000 European Union citizens and 135.000 citizens with other nationalities are second- class citizens in this city-region, since they are excluded from the democratic process. And yet they are Brusseleirs like everyone else—who live, love, work, study, pay taxes and contribute in so many ways to make Brussels-Capital a better home for everyone. These 415,000 Brusseleirs who are excluded, do not have a say on decisions that affect their day-to-day lives, such as mobility and public transport, urban planning and heritage, parks and green spaces, waste and recycling, infrastructure and public works, pollution and air quality, energy and sustainable development, family allocations and education as well as budget. It is true that all inhabitants of Brussels-Capital, regardless of nationality, can vote in local « communal elections ». But this is an insufficient right because it is fragmented across the 19 communes. While it is at the level of the Brussels-Capital Region, one of the three federal entities in Belgium, that Brusseleirs' life is really organized, and that significant decisions - and policy-making take place. -

Le Statut De Bruxelles Et De Sa Région

Le statut de Bruxelles et de sa région UN BREF PORTRAIT Hecke a défini la dimension de la région DE BRUXELLES bruxelloise. Il a obtenu deux définitions, l'une minimaliste, l'autre maximaliste. À la date du Capitale de la Belgique, Bruxelles cumule 1er décembre 1973, il alignait les résultats plusieurs qualités. Le nom de Bruxelles suivants: recouvre une agglomération au même titre -région bruxelloise selon la définition minima qu'Anvers ou Liège, une région politique au liste: 1 289 600 hab. soit 40 communes même titre que la Flandre ou la Wallonie, une - région bruxelloise selon la définition maxi région linguistique à statut spécial car y maliste: 1 348 600 hab. soit 50 communes. coexistent deux communautés en proportions Plusieurs autres études ont été faites qui très inégales. Mais sur l'étendue de ces entités, aboutissent à de semblables conclusions. Ain les avis diffèrent, les convictions s'affrontent. si, notamment, M. B. Jouret a conclu que Bruxelles est en outre un centre économique de pour mener à bien son rôle, l'agglomération première importance. Depuis une quinzaine devrait s'étendre sur soixante et une commu d'années, elle est devenue, de fait, la capitale nes. M. P. Guillain, dans le journal Vers de l'Europe. l'Avenir a défini en 1969 l'aire bruxelloise à Ce sont ces divers aspects qu'il convient partir des taux d'expansion de la population d'étudier successivement. Mais, avant toute entre 1947 et 1967. Il a rattaché à la région chose, une brève présentation de cette commu bruxelloise les communes périphériques où le nauté urbaine originale qu'est Bruxelles s'im taux d'expansion de la population dépassait le pose. -

BPH Achituv, Alon (12) 0471/58.17.76 Ixelles, Uccle [email protected]

ISB Students Available for Baby/Child-sitting, Pet-sitting and House-sitting The students listed below have indicated their willingness to do babysitting, pet sitting and/or housesitting. The inclusion of their names in this list does not imply a recommendation and any arrangements made are strictly a private matter between the family and the student for which the school accepts no responsibility. BPH Achituv, Alon (12) 0471/58.17.76 Ixelles, Uccle [email protected] BPH Albos, Maxime (11) 0474/04.37.82 Auderghem, Etterbeek, Ixelles [email protected] Watermael-Boitsfort, Woluwe-St-Pierre Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday (after 16:00) B Archambeau, Alix (10) 0471/85.12.99 Ixelles, Uccle [email protected] Saturday, Sunday BPH Baz, Marina (12) 0493/65.65.65 Ixelles, Uccle [email protected] Week-ends (and sometimes on week days) BPH Beaume, Rafael (11) 0497/60.38.94 Ixelles, Watermael-Boitsfort [email protected] Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, (some Saturdays and Sundays from 7:30PM onwards). I am 15 and speak English, French and Spanish B Bishop, Menna (11) 0498/47.12.20 or 0497/29.70.78 Brussels area, Genval, Hoeilaart, La Hulpe, Overijse [email protected] Available with short notice BPH Brandon, Matthew (10) 0497/17.34.86 Overijse [email protected] I am a responsible student. I can be of help with short notice. I am unreachable by phone during school hours. BP Caruso, Maddy (10) 0477/93.06.68 Etterbeek [email protected] May not be available a lot of weekends (Friday nights, Saturday morning/afternoons) because of ISB sports BPH Casteels, Dana (12) 0493/62.14.15 Hoeilaert, La Hulpe, Overijse - any surrounding areas [email protected] Every day except Monday evenings, and Wednesday after school BH Daelemans, Axelle (12) 0477/38.88.45 Forest, Ixelles, St. -

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles BELGIUM

Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles BELGIUM by Alain Peeters The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. All rights reserved. FAO encourages the reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. © FAO 2010 3 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 Country location 5 2. SOILS AND TOPOGRAPHY 8 Topography and geology 8 Soil types 10 3. CLIMATE AND AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES 11 Climate 11 Geographical regions 13 Agro-ecological regions 14 Forests 22 4. -

Route Description

Brussels Route Description Baker McKenzie is located in the Generali tower, situated at Avenue Louise-Louizalaan 149, in the centre of Brussels. Our reception is on the 11th floor Parking facilities Route Do not take the exit "Louiza", Do keep right and ± 50 m From Antwerp: Generali-building further (still in the tunnel) Highway E19 Antwerp - turn right, exit "Ter Kameren At the traffic lights, in front of Brussels the Generali-building, turn Bos" right in the Defacqzstraat-rue Ringroad (direction Ostend - Defacqz. Ghent - Bergen - leave the tunnel at the first Charleroi...) exit. Continue for 50 m until the first cross roads Exit Brussels Centre - At the Louizalaan straight Koekelberg ahead for ± 200 m until the Turn left traffic lights (cross road with The underground parking lot Always straight ahead "Defacqzstraatrue Defacqz") (Keizer Karellaan-Avenue is at about 30 m on your left Charles Quint) Obliquely in front of you, on side (Parking Tour Louise) your right, is the Generali- In front of basilica building. (Koekelberg): take tunnel Aboveground Leopold II From Liège There are parking places just in Do not take the exit "Louiza", front of the Generali-building Do keep right and ± 50 m From Liege (Louizalaan-avenue Louise). further (still in the tunnel) Highway E40 Liege - turn right, exit "Ter Kameren Brussels Bos" Public Transport Follow direction Centre Leave the tunnel at the first ("Kortenbergtunnel-Tunnel Our offices are easy to reach by exit. de Cortenbergh") public transport: At the Louizalaan straight At the "Kortenberglaan- ahead for ± 200 m until the Avenue de Cortenbergh In the "Zuid Station" (Midi traffic lights (crossroad with "follow the road until the Station) take the subway "Defazqzstraat-rue "SchumannpleinPlace direction "Simonis - Defacqz") Schumann" Elisabeth". -

BCT Info Team

Brussels Childbirth Trust www.bctbelgium.org Gynaecologists in Brussels and surroundings Phone Name Town Address Number Sex Languages spoken DONNER, CATHERINE ANDERLECHT HOPITAL ERASME. ROUTE DE LENNIK 808 02 555 3111 F FRENCH BOSUMA, BAKILI W'OKUNGA BRAINE L'ALLEUD HOPITAL BRAINE L'ALLEUD, RUE WAYEZ 35 02 389 0439 M FRENCH, ENGLISH BUSINE, ALAINE BRAINE L'ALLEUD HOPITAL BRAINE L'ALLEUD, RUE WAYEZ 35 02 389 0439 M FRENCH DELANDE, ISABELLE BRAINE L'ALLEUD HOPITAL BRAINE L'ALLEUD, RUE WAYEZ 35 02 389 0439 F FRENCH, ENGLISH GREINDL, JACQUELINE BRAINE L'ALLEUD HOPITAL BRAINE L'ALLEUD, RUE WAYEZ 35 02 389 0439 F FRENCH, ENGLISH GIELEN, FRANCOIS WATERLOO AV DU CHAMP DE MAI 8 02 351 0780 M ENGLISH STRIJDERSSTRAAT 24, (UZA-UNIVERSITY JACQUEMYN, YVES EDEGEM HOSPITAL ANTWERP) 03 458 4004 M FRENCH, ENGLISH, DUTCH CENTRE MEDICAL MONTGOMERY, AV DE BERBALK-NUHN, KARIN ETTERBEEK L'ARMÉE 14 02 735 0252 F FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN BUKERA, ALINE ETTERBEEK CLINIQUE ST MICHEL, RUE DE LINTHOUT 150 02 614 3730 F FRENCH CENTRE MEDICAL MONTGOMERY, AV DE CAYPHAS, CHRISTOPHE ETTERBEEK L'ARMÉE 14 02 735 0252 M FRENCH, ENGLISH CLAES, JEAN-PIERRE ETTERBEEK RUE FROISSART 38 02 287 5783 M FRENCH, ENGLISH CENTRE MEDICAL MONTGOMERY, AV DE GANS, ANDRE ETTERBEEK L'ARMÉE 14 02 735 0252 M FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN HIS IXELLES-ETTERBEEK, RUE BARON KARLIN, SOPHIE ETTERBEEK LAMBERT 38 02 7398585 F FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN BALASSE, HÉLÈNE FOREST AV MOLIERE 145 02 345 5866 F FRENCH, ENGLISH NAOME, GENEVIÈVE FOREST AV ST-AUGUSTIN 23 02 343 9647 F FRENCH CENTRE HOSPITALIER ETTERBEEK, AV DU BOSSENS, M IXELLES MARECHAL 21 02 374 2408 M FRENCH, ENGLISH C.MED. -

Report on 50 Years of Mobility Policy in Bruges

MOBILITEIT REPORT ON 50 YEARS OF MOBILITY POLICY IN BRUGES 4 50 years of mobility policy in Bruges TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by Burgomaster Dirk De fauw 7 Reading guide 8 Lexicon 9 Research design: preparing for the future, learning from the past 10 1. Once upon a time there was … Bruges 10 2. Once upon a time there was … the (im)mobile city 12 3. Once upon a time there was … a research question 13 1 A city-wide reflection on mobility planning 14 1.1 Early 1970s, to make a virtue of necessity (?) 14 1.2 The Structure Plan (1972), a milestone in both word and deed 16 1.3 Limits to the “transitional scheme” (?) (late 1980s) 18 1.4 Traffic Liveability Plan (1990) 19 1.5 Action plan ‘Hart van Brugge’ (1992) 20 1.6 Mobility planning (1996 – present) 21 1.7 Interim conclusion: a shift away from the car (?) 22 2 A thematic evaluation - the ABC of the Bruges mobility policy 26 5 2.1 Cars 27 2.2 Buses 29 2.3 Circulation 34 2.4 Heritage 37 2.5 Bicycles 38 2.6 Canals and bridges 43 2.7 Participation / Information 45 2.8 Organisation 54 2.9 Parking 57 2.10 Ring road(s) around Bruges 62 2.11 Spatial planning 68 2.12 Streets and squares 71 2.13 Tourism 75 2.14 Trains 77 2.15 Road safety 79 2.16 Legislation – speed 83 2.17 The Zand 86 3 A city-wide evaluation 88 3.1 On a human scale (objective) 81 3.2 On a city scale (starting point) 90 3.3 On a street scale (means) 91 3.4 Mobility policy as a means (not an objective) 93 3.5 Structure planning (as an instrument) 95 3.6 Synthesis: the concept of ‘city-friendly mobility’ 98 3.7 A procedural interlude: triggers for a transition 99 Archives and collections 106 Publications 106 Websites 108 Acknowledgements 108 6 50 years of mobility policy in Bruges DEAR READER, Books and articles about Bruges can fill entire libraries.