And 10Th- Century Flanders and Zeeland As Markers of the Territorialisation of Power(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Channel Ground-Penetrating Radar Array Surveys of the Iron Age and Medieval Ringfort Bårby on the Island of Öland, Sweden

remote sensing Article Multi-Channel Ground-Penetrating Radar Array Surveys of the Iron Age and Medieval Ringfort Bårby on the Island of Öland, Sweden Andreas Viberg 1,* , Christer Gustafsson 2 and Anders Andrén 3 1 Archaeological Research Laboratory, Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2 ImpulseRadar AB, Storgatan 78, SE–939 32 Malå, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 December 2019; Accepted: 4 January 2020; Published: 9 January 2020 Abstract: As a part of the project “The Big Five”, large-scale multi-channel ground-penetrating radar surveys were carried out at Bårby ringfort (Swedish: borg), Öland, Sweden. The surveys were carried out using a MALÅ Imaging Radar Array (MIRA) system and aimed at mapping possible buried Iron Age and Medieval remains through the interior in order to better understand the purpose of the fort during its periods of use. An additional goal was to evaluate the impact of earlier farming on the preservation of the archaeological remains. The data provided clear evidence of well-preserved Iron Age and Medieval buildings inside the fort. The size and the pattern of the Iron Age houses suggest close similarities with, for example, the previously excavated fort at Eketorp on Öland. Given the presence of a substantial cultural layer together with a large number of artefacts recovered during a metal detection survey, it is suggested that Bårby borg’s primary function during the Iron Age was as a fortified village. -

Brussels Aterloose Charleroisestwg

E40 B R20 . Leuvensesteenweg Ninoofsestwg acqmainlaan J D E40 E. oningsstr K Wetstraat E19 an C ark v Belliardstraat Anspachlaan P Brussel Jubelpark Troonstraat Waterloolaan Veeartsenstraat Louizalaan W R20 aversestwg. T Kroonlaan T. V erhaegenstr Livornostraat . W Louizalaan Brussels aterloose Charleroisestwg. steenweg Gen. Louizalaan 99 Avenue Louise Jacqueslaan 1050 Brussels Alsembergsesteenweg Parking: Brugmannlaan Livornostraat 14 Rue de Livourne A 1050 Brussels E19 +32 2 543 31 00 A From Mons/Bergen, Halle or Charleroi D From Leuven or Liège (Brussels South Airport) • Driving from Leuven on the E40 motorway, go straight ahead • Driving from Mons on the E19 motorway, take exit 18 of the towards Brussels, follow the signs for Centre / Institutions Brussels Ring, in the direction of Drogenbos / Uccle. européennes, take the tunnel, and go straight ahead until you • Continue straight ahead for about 4.5 km, following the tramway reach the Schuman roundabout. (the name of the road changes : Rue Prolongée de Stalle, Rue de • Take the 2nd road on the right to Rue de la Loi. Stalle, Avenue Brugmann, Chaussée de Charleroi). • Continue straight on until you cross the Small Ring / Boulevard du • About 250 metres before Place Stéphanie there are traffic lights: at Régent. Turn left and take the small Ring (tunnels). this crossing, turn right into Rue Berckmans. At the next crossing, • See E turn right into Rue de Livourne. • The entrance to the car park is at number 14, 25 m on the left. E Continue • Follow the tunnels and drive towards La Cambre / Ter Kameren B From Ghent (to the right) in the tunnel just after the Louise exit. -

5. Excavation of a Ringfort at Leggetsrath West, County Kilkenny Anne-Marie Lennon

5. Excavation of a ringfort at Leggetsrath West, County Kilkenny Anne-Marie Lennon Illus. 1—Location of the Leggetsrath West ringfort, Co. Kilkenny (based on Ordnance Survey Ireland map) The ringfort at Leggetsrath West was situated to the east of Kilkenny city, on the proposed route of the N77 Kilkenny Ring Road Extension (Illus. 1). The site was identified in a preliminary archaeological assessment of the road corridor as an area of potential archaeological interest. It was the only high point, a naturally occurring hillock, along the route of the proposed road. The site was in an area of rough grazing, which was bound to the east by the Fennell stream and to the west by Hebron Industrial Estate. Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd carried out investigations in 2004 when the gravel hillock was topsoil stripped, revealing a bivallate (double ditch) ringfort dating from the early historic period (NGR 252383, 155983; height 58.47 m OD; excavation licence no. 04E0661). The ringfort was delimited by two concentric ditches set 4 m apart, with an overall diameter of 54 m. Archaeological excavations were funded by the National Roads Authority through Kilkenny County Council. Historical and archaeological background The early historic period in Ireland is dominated by the introduction of Christianity in the fifth century AD. Apart from church sites, the settlement evidence of the period is 43 Settlement, Industry and Ritual Illus. 2—Plan of excavated features at Leggetsrath West (Archaeological Consultancy Services Ltd) 44 A ringfort at Leggetsrath West, County Kilkenny dominated by two categories of monument: the ringfort and the crannóg. -

Crannogs — These Small Man-Made Islands

PART I — INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION Islands attract attention.They sharpen people’s perceptions and create a tension in the landscape. Islands as symbols often create wish-images in the mind, sometimes drawing on the regenerative symbolism of water. This book is not about natural islands, nor is it really about crannogs — these small man-made islands. It is about the people who have used and lived on these crannogs over time.The tradition of island-building seems to have fairly deep roots, perhaps even going back to the Mesolithic, but the traces are not unambiguous.While crannogs in most cases have been understood in utilitarian terms as defended settlements and workshops for the wealthier parts of society, or as fishing platforms, this is not the whole story.I am interested in learning more about them than this.There are many other ways to defend property than to build islands, and there are many easier ways to fish. In this book I would like to explore why island-building made sense to people at different times. I also want to consider how the use of islands affects the way people perceive themselves and their landscape, in line with much contemporary interpretative archaeology,and how people have drawn on the landscape to create and maintain long-term social institutions as well as to bring about change. The book covers a long time-period, from the Mesolithic to the present. However, the geographical scope is narrow. It focuses on the region around Lough Gara in the north-west of Ireland and is built on substantial fieldwork in this area. -

National Monuments Preservation Orders & Listing Orders

Draft County Development Plan Appendices Appendix H National Monuments Preservation Orders & Listing Orders National monuments protected by the State under the Monuments Acts, 1930, 1954 (Amended 1987) Aghaviller Church and round tower Ballylarkin upper Church Burnchurch Castle and tower Callan south St. Mary’s church Callan north Augustinian friary Callan north Motte Castletown Kilkieran high crosses Clara upper Castle Clonamery Church Gowran Ruined part of St MaryÆs Grange Fertagh Church and round tower Grannagh Granagh castle Grenan Templeteahan (in ruins) Jerpoint Cistercian abbey Kilfane desmesne Kilfane church and graveyard Killamery High cross Kilmogue Portal dolmen Kilree Church Kilree Round tower Kilree Cross Knocktopher Church tower Mohil Dunmore cave Rathealy Rath Rathduff (Madden) Kells augustinian priory Sheepstown Church (in ruins) Tullaherin Tullaherin church (in ruins) Ullard Church (in ruins) Raheenarran Moated house site Monuments protected by Preservation Orders Townland Monument Baleen Tower Carigeen Ring fort Danesfort Ring fort Dunbell big Ring fort Graiguenamanagh Duiske Abbey Jerpoint Church Jerpoint Abbey Powerstown east Motte and bailey Tullaroan Ring fort Moat park Motte and bailey Raheenarran Moated house site H-1 Draft County Development Plan Appendices Monuments to be protected by Listing Orders / Registration Townland Monument Goslingtown Tower House Church Hill Ring fort Gowran Desmesne Ballyshanemore Castle Grenan Castle Kells Motte and Bailey Pottlerath Dovecote Garrynamann Lower Motte Ballyfereen Moun -

Brussels 1 Brussels

Brussels 1 Brussels Brussels • Bruxelles • Brussel — Region of Belgium — • Brussels-Capital Region • Région de Bruxelles-Capitale • Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest A collage with several views of Brussels, Top: View of the Northern Quarter business district, 2nd left: Floral carpet event in the Grand Place, 2nd right: Brussels City Hall and Mont des Arts area, 3rd: Cinquantenaire Park, 4th left: Manneken Pis, 4th middle: St. Michael and St. Gudula Cathedral, 4th right: Congress Column, Bottom: Royal Palace of Brussels Flag Emblem [1] [2][3] Nickname(s): Capital of Europe Comic city Brussels 2 Location of Brussels(red) – in the European Union(brown & light brown) – in Belgium(brown) Coordinates: 50°51′0″N 4°21′0″E Country Belgium Settled c. 580 Founded 979 Region 18 June 1989 Municipalities Government • Minister-President Charles Picqué (2004–) • Governor Jean Clément (acting) (2010–) • Parl. President Eric Tomas Area • Region 161.38 km2 (62.2 sq mi) Elevation 13 m (43 ft) [4] Population (1 January 2011) • Region 1,119,088 • Density 7,025/km2 (16,857/sq mi) • Metro 1,830,000 Time zone CET (UTC+1) • Summer (DST) CEST (UTC+2) ISO 3166 BE-BRU [5] Website www.brussels.irisnet.be Brussels (French: Bruxelles, [bʁysɛl] ( listen); Dutch: Brussel, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫ] ( listen)), officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region[6][7] (French: Région de Bruxelles-Capitale, [ʁe'ʒjɔ̃ də bʁy'sɛlkapi'tal] ( listen), Dutch: Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest, Dutch pronunciation: [ˈbrʏsəɫs ɦoːft'steːdələk xəʋɛst] ( listen)), is the capital -

Lesson Plan 5: Threecastles Ringfort & Motte

Lesson Plan 5: Threecastles Ringfort & Motte This lesson is part of a series of 8 lesson plans based on the “Explore the Nore” poster and River Nore Heritage Audit. It is aimed at 4th, 5th & 6th classes in primary schools. The project is an action of the Kilkenny Heritage Plan, and is funded by the Heritage Office of Kilkenny County Council and the Heritage Council. For further information contact [email protected]. Tel: 056- 7794925. www.kilkennycoco.ie/eng/Services/Heritage/ Learning objectives HISTORY Strand: Local studies; Strand unit: Buildings, sites or ruins in my locality; Strand unit: My locality through the ages Strand: Early people and ancient societies ; Strand unit: Early Christian Ireland Strand: Life, society, work and culture in the past; Strand unit: Life in Norman Ireland Content objectives • develop an understanding of chronology, in order to place people, events and topics studied in a broad historical sequence use imagination and evidence to reconstruct elements of the past develop a sense of responsibility for, and a willingness to participate in, the preservation of heritage Skills and concepts to be developed time and chronology change and continuity using evidence Learning activities Threecastles Ringfort and Motte Lesson plan: visual cues from the poster photograph. Get students to answer a series of questions on the Threecastles ringfort photograph. Consult wider resources to answer some of the questions. Rele- vant to Early Medieval Ireland (500-1200 AD) and the start of the Anglo Norman period (1200-1400 AD) Can you see the ringfort at Threecastles? It is the bullseye in the brown field in the middle of the poster. -

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent

Hillforts: Britain, Ireland and the Nearer Continent Papers from the Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland Conference, June 2017 edited by Gary Lock and Ian Ralston Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-226-6 ISBN 978-1-78969-227-3 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover images: A selection of British and Irish hillforts. Four-digit numbers refer to their online Atlas designations (Lock and Ralston 2017), where further information is available. Front, from top: White Caterthun, Angus [SC 3087]; Titterstone Clee, Shropshire [EN 0091]; Garn Fawr, Pembrokeshire [WA 1988]; Brusselstown Ring, Co Wicklow [IR 0718]; Back, from top: Dun Nosebridge, Islay, Argyll [SC 2153]; Badbury Rings, Dorset [EN 3580]; Caer Drewyn Denbighshire [WA 1179]; Caherconree, Co Kerry [IR 0664]. Bottom front and back: Cronk Sumark [IOM 3220]. Credits: 1179 courtesy Ian Brown; 0664 courtesy James O’Driscoll; remainder Ian Ralston. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ii -

Arrangement of Space Inside Ölandic Ringforts a Comparative Study of the Spatial Division Within the Ringforts Eketorp, Sandby, and Ismantorp

Arrangement of space inside Ölandic ringforts A comparative study of the spatial division within the ringforts Eketorp, Sandby, and Ismantorp Lund University The Joint Faculties of Humanities and Theology Department of Archaeology and Ancient History ARKM21, Archaeology and Ancient History: Master Thesis in Archaeology Spring semester 2019 Supervisor: Nicoló Dell'Unto Author: Fraya-Noëlle Denninghaus Abstract In the Iron Age AD, ringforts were constructed on the Swedish island Öland. Most of them contained a settlement inside. The remains of 15 of these ringforts are still preserved in the landscape. This thesis gives a general overview of the known and the possible Ölandic ringforts and their historical and constructional context, before analysing and comparing the settlements inside the ringforts Eketorp, Sandby, and Ismantorp regarding their spatial division and arrangement. At that, the focus lays on the main settlement phases in the Iron Age. The analysis was conducted to explore if there is a pattern in the arrangement of the settlements inside the ringforts and further to investigate the importance of sufficient open areas. In doing so, the arrangement and grouping of houses and open areas, the relation of built-up and open space, as well as the development of the respective interior settlement are analysed. The ringforts were an isolated and small settlement complex. Thus, usually there were houses with different kinds of functions (e.g. dwellings, stables, storehouses, workshops) within the ringforts. The results of this study show that there was more built-up space than open space inside each of the analysed ringforts. It is to assume that the open areas were used as public space respectively settlement squares. -

British Archaeological Reports TITLES in PRINT January 2011 – BAR International Series

British Archaeological Reports TITLES IN PRINT January 2011 – BAR International Series The BAR series of archaeological monographs were started in 1974 by Anthony Hands and David Walker. From 1991, the publishers have been Tempus Reparatum, Archaeopress and John and Erica Hedges. From 2010 they are published exclusively by Archaeopress. Descriptions of the Archaeopress titles are to be found on www.archaeopress.com Publication proposals to [email protected] Sign up to our new ALERTS SERVICE via our above website homepage Find us on Facebook www.facebook.com/Archaeopress. and Twitter www.twitter.com/archaeopress BAR –S58, 1979 Greek Bronze Hand-Mirrors in South Italy by Fiona Cameron. ISBN 0 86054 056 1. £13.00. BAR –S99 1981 The Defence of Byzantine Africa from Justinian to the Arab Conquest: An account of the military history and archaeology of the African provinces in the sixth and seventh centuries by Reginald Denys Pringle. ISBN 1 84171 184 5. £100.00. BAR –S209, 1984 Son Fornés I La Fase Talayotica. Ensayo de reconstrucción socio-ecónomica de una comunidad prehistórica de la isla de Mallorca by Pepa Gasull, Vincente Lull y Ma. Encama Sanahuja. ISBN 0 86054 270 X. £25.00. BAR –S235, 1985 Mexica Buried Offerings A Historical and Contextual Analysis by Debra Nagao. ISBN 0 86054 305 6. £22.00. BAR –S238, 1985 Holocene Settlement in North Syria ed. Paul Sanlaville. Maison de L’Orient Mediterranéen (C.N.R.S. - Université Lyon 2), Lyon, France, Archaeological Series No. 1. ISBN 0 86054 307 2. £18.00. BAR –S240, 1985 Peinture murale en Gaule Actes des séminaires AFPMA 1982-1983: 1er et 2 mai 1982 à Lisieux, 21 et 22 mai 1983 à Bordeaux coordination Alix Barbet. -

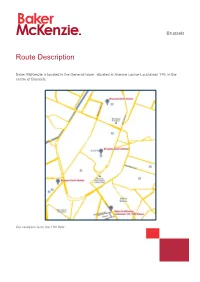

Route Description

Brussels Route Description Baker McKenzie is located in the Generali tower, situated at Avenue Louise-Louizalaan 149, in the centre of Brussels. Our reception is on the 11th floor Parking facilities Route Do not take the exit "Louiza", Do keep right and ± 50 m From Antwerp: Generali-building further (still in the tunnel) Highway E19 Antwerp - turn right, exit "Ter Kameren At the traffic lights, in front of Brussels the Generali-building, turn Bos" right in the Defacqzstraat-rue Ringroad (direction Ostend - Defacqz. Ghent - Bergen - leave the tunnel at the first Charleroi...) exit. Continue for 50 m until the first cross roads Exit Brussels Centre - At the Louizalaan straight Koekelberg ahead for ± 200 m until the Turn left traffic lights (cross road with The underground parking lot Always straight ahead "Defacqzstraatrue Defacqz") (Keizer Karellaan-Avenue is at about 30 m on your left Charles Quint) Obliquely in front of you, on side (Parking Tour Louise) your right, is the Generali- In front of basilica building. (Koekelberg): take tunnel Aboveground Leopold II From Liège There are parking places just in Do not take the exit "Louiza", front of the Generali-building Do keep right and ± 50 m From Liege (Louizalaan-avenue Louise). further (still in the tunnel) Highway E40 Liege - turn right, exit "Ter Kameren Brussels Bos" Public Transport Follow direction Centre Leave the tunnel at the first ("Kortenbergtunnel-Tunnel Our offices are easy to reach by exit. de Cortenbergh") public transport: At the Louizalaan straight At the "Kortenberglaan- ahead for ± 200 m until the Avenue de Cortenbergh In the "Zuid Station" (Midi traffic lights (crossroad with "follow the road until the Station) take the subway "Defazqzstraat-rue "SchumannpleinPlace direction "Simonis - Defacqz") Schumann" Elisabeth". -

Report on 50 Years of Mobility Policy in Bruges

MOBILITEIT REPORT ON 50 YEARS OF MOBILITY POLICY IN BRUGES 4 50 years of mobility policy in Bruges TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by Burgomaster Dirk De fauw 7 Reading guide 8 Lexicon 9 Research design: preparing for the future, learning from the past 10 1. Once upon a time there was … Bruges 10 2. Once upon a time there was … the (im)mobile city 12 3. Once upon a time there was … a research question 13 1 A city-wide reflection on mobility planning 14 1.1 Early 1970s, to make a virtue of necessity (?) 14 1.2 The Structure Plan (1972), a milestone in both word and deed 16 1.3 Limits to the “transitional scheme” (?) (late 1980s) 18 1.4 Traffic Liveability Plan (1990) 19 1.5 Action plan ‘Hart van Brugge’ (1992) 20 1.6 Mobility planning (1996 – present) 21 1.7 Interim conclusion: a shift away from the car (?) 22 2 A thematic evaluation - the ABC of the Bruges mobility policy 26 5 2.1 Cars 27 2.2 Buses 29 2.3 Circulation 34 2.4 Heritage 37 2.5 Bicycles 38 2.6 Canals and bridges 43 2.7 Participation / Information 45 2.8 Organisation 54 2.9 Parking 57 2.10 Ring road(s) around Bruges 62 2.11 Spatial planning 68 2.12 Streets and squares 71 2.13 Tourism 75 2.14 Trains 77 2.15 Road safety 79 2.16 Legislation – speed 83 2.17 The Zand 86 3 A city-wide evaluation 88 3.1 On a human scale (objective) 81 3.2 On a city scale (starting point) 90 3.3 On a street scale (means) 91 3.4 Mobility policy as a means (not an objective) 93 3.5 Structure planning (as an instrument) 95 3.6 Synthesis: the concept of ‘city-friendly mobility’ 98 3.7 A procedural interlude: triggers for a transition 99 Archives and collections 106 Publications 106 Websites 108 Acknowledgements 108 6 50 years of mobility policy in Bruges DEAR READER, Books and articles about Bruges can fill entire libraries.