View Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fur Mites (Acari: Listrophoridae) of the Round-Tailed Muskrat, Neofiber Alieni

919 Bull. Ann1s Soc. r. be1ge Ent. 122 (1986): 171-181 The fur mites (Acari: Listrophoridae) of the Round-tailed Muskrat, Neofiber alIeni by A. FAIN°o, M. A. SMITHooo and J. O. WHITAKER Jrooo Abstract Three new species of fur mites of the family Listrophoridae (Acari) are described from the Round-tailed Muskrat Neofiber alIeni, from Florida, U.S.A. They are Listrophorus laynei sp. n., L. caudatus sp. n. and Prolistrophorus birkenholzi sp. n. Resume Trois nouvelles especes d'acariens pilicoles de la famille Listrophoridae (Acari) sont decrites de Neofiber alIeni, des U.S.A.: Listrophorus laynei sp. n., L. caudatus sp. n. et Prolistrophorus birkenholzi sp. n. BIRKENHOLZ (1963) reported that nearly all Round-tailed muskrats, Neofober aJJeni, he examined were infested with "Listrophoridae, probably an undescribed species." We have now collected additional material from this host and herein describe three new species ofListrophoridae (Acari). Seventeen Round-tailed Muskrats, mostly collected by James N. Layne, were examined for parasites by M.A.S., along with mites from 8 additional muskrats collected earlier by Layne. The muskrats included were collected between 1968 and 1984. Further information on abundance and occurrence on the host will be presented later. Two of the species belong to the genus Listrophorus PAGENSTECHER, 1861 (L. 1aynei sp. n. and L. caudatus sp. n.) and one to the genus ProJistrophorus FAIN, 1970 (P. birkenho1zi sp. n.). Fur mites of other groups (Myobiidae, Myocoptidae and hypopi of Glycyphagidae) were not regularly found on Neofiber aJJeni. The mite fauna of this rodent appears therefore much poorer than that of the Muskrat, Ondatra zibethicus, another species o Depose le 5 novembre 1985. -

Upper Cretaceous Sequences and Sea-Level History, New Jersey Coastal Plain

Upper Cretaceous sequences and sea-level history, New Jersey Coastal Plain Kenneth G. Miller² Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA Peter J. Sugarman New Jersey Geological Survey, P.O. Box 427, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, USA James V. Browning Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA Michelle A. Kominz Department of Geosciences, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan 49008-5150, USA Richard K. Olsson Mark D. Feigenson John C. HernaÂndez Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA ABSTRACT pean sections, and Russian platform BACKGROUND outcrops points to a global cause. Because We developed a Late Cretaceous sea- backstripping, seismicity, seismic strati- Predictable, recurring sequences bracketed level estimate from Upper Cretaceous se- graphic data, and sediment-distribution by unconformities comprise the building quences at Bass River and Ancora, New patterns all indicate minimal tectonic ef- blocks of the stratigraphic record. Exxon Pro- Jersey (ODP [Ocean Drilling Program] Leg fects on the New Jersey Coastal Plain, we duction Research Company (EPR) de®ned a 174AX). We dated 11±14 sequences by in- interpret that we have isolated a eustatic depositional sequence as a ``stratigraphic unit tegrating Sr isotope and biostratigraphy signature. The only known mechanism composed of a relatively conformable succes- (age resolution 60.5 m.y.) and then esti- that can explain such global changesÐ sion of genetically related strata and bounded mated paleoenvironmental changes within glacio-eustasyÐis consistent with forami- at its top and base by unconformities or their the sequences from lithofacies and biofacies niferal d18O data. -

DINOQUEST: a TROPICAL TREK THROUGH TIME Featured Dinosaurs and Reptiles

DINOQUEST: A TROPICAL TREK THROUGH TIME Featured Dinosaurs and Reptiles BAMBIRAPTORS (AND EGG NEST) (BAM-bee-RAP-tors) Name Means : “Baby Raider” Description : A tiny, bird-like dinosaur that is believed to have been covered in feathers and fuzz, similar to that of a baby bird. It had long arms and hands, with a mouth full of sharp teeth and a claw similar to that of the Velociraptor. Lived : Late Cretaceous period Fossils Found : Montana, U.S. Fun Fact : Bambiraptor is an important piece of the puzzle linking dinosaurs to birds. A 90-percent complete skeleton was discovered by a 14-year-old boy in 1995. Installation Dimensions : Four four-foot-long dinosaurs; two 30-inch-diameter egg nests CITIPATI (AND EGG NEST) (sit-ih-PA-tee) Name Means : “Funeral Pyre Lord” Description : Citipati’s skull was unusually short and ended in a toothless beak. It is one of the best known of the bird-like dinosaurs. It has an unusually long neck and shortened tail, compared to most other theropods. Lived : Cretaceous period Fossils Found : Mongolia Fun Fact : At least four specimens of Citipati have been found sitting on their nests, indicating that Citipati took care of its young like modern birds. Installation Dimensions : Three three-and-a-half-foot-long dinosaurs; two 30-inch-diameter egg nests COMPSOGNATHUS (AND EGG NEST) (komp-sog-NAY-thus) Name Means : “Pretty Jaw” Description : The Compsognathus was a bird-like carnivore with short arms, two-clawed fingers, long legs and three-toed feet. It had a long neck and small head with pointy teeth. -

Parasite Communities of Tropical Forest Rodents: Influences of Microhabitat Structure and Specialization

PARASITE COMMUNITIES OF TROPICAL FOREST RODENTS: INFLUENCES OF MICROHABITAT STRUCTURE AND SPECIALIZATION By Ashley M. Winker Parasitism is the most common life style and has important implications for the ecology and evolution of hosts. Most organisms host multiple species of parasites, and parasite communities are frequently influenced by the degree of host specialization. Parasite communities are also influenced by their habitat – both the host itself and the habitat that the host occupies. Tropical forest rodents are ideal for examining hypotheses relating parasite community composition to host habitat and host specialization. Proechimys semispinosus and Hoplomys gymnurus are morphologically-similar echimyid rodents; however, P. semispinosus is more generalized, occupying a wider range of habitats. I predicted that P. semispinosus hosts a broader range of parasite species that are less host-specific than does H. gymnurus and that parasite communities of P. semispinosus are related to microhabitat structure, host density, and season. During two dry and wet seasons, individuals of the two rodent species were trapped along streams in central Panama to compare their parasites, and P. semispinosus was sampled on six plots of varying microhabitat structure in contiguous lowland forest to compare parasite loads to microhabitat structure. Such structure was quantified by measuring thirteen microhabitat variables, and dimensions were reduced to a smaller subset using factor analysis to define overall structure. Ectoparasites were collected from each individual, and blood smears were obtained to screen for filarial worms and trypanosomes. In support of my prediction, the habitat generalist ( P. semispinosus ) hosted more individual fleas, mites, and microfilaria; contrary to my prediction, the habitat specialist (H. -

Note on the Sauropod and Theropod Dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Madagascar*

EXTRACT FROM THE BULLETIN DE LA SOCIÉTÉ GÉOLOGIQUE DE FRANCE 3rd series, volume XXIV, page 176, 1896. NOTE ON THE SAUROPOD AND THEROPOD DINOSAURS FROM THE UPPER CRETACEOUS OF MADAGASCAR* by Charles DEPÉRET. (PLATE VI). Translated by Matthew Carrano Department of Anatomical Sciences SUNY at Stony Brook, September 1999 The bones of large dinosaurian reptiles described in this work were brought to me by my good friend, Mr. Dr. Félix Salètes, primary physician for the Madagascar expedition, from the environs of Maevarana, where he was charged with installing a provisional hospital. This locality is situated on the right bank of the eastern arm of the Betsiboka, 46 kilometers south of Majunga, on the northwest coast of the island of Madagascar. Not having the time to occupy himself with paleontological studies, Dr. Salètes charged one of his auxiliary agents, Mr. Landillon, company sergeant-major of the marines, with researching the fossils in the environs of the Maevarana post. Thanks to the zeal and activity of Mr. Landillon, who was not afraid to gravely expose his health in these researches, I have been able to receive the precious bones of terrestrial reptiles that are the object of this note, along with an important series of fossil marine shells. I eagerly seize the opportunity here to thank Mr. Landillon for his important shipment and for the very precise geological data which he communicated to me concerning the environs of Maevarana, and of which I will now give a short sketch. 1st. Geology of Maevarana and placement of the localities. * Original reference: Depéret, C. -

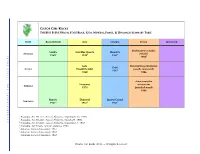

State Rocks Table.Pdf

GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Basilosaurus cetoides Marble Star Blue Quartz Hematite ALABAMA [whale] 19691 19902 19673 19844 Jade Mammuthus primigenius Gold ALASKA [Nephrite Jade] [woolly mammoth] 1967 1968 1986 STATE ROCKS STATE – Araucarioxylon Turquoise arizonicum ARIZONA 1974 [petrified wood] 1988 Bauxite Diamond Quartz Crystal ARKANSAS 19675 19676 19677 1 Alabama, Act 69-755, Acts of Alabama, September 12, 1969. 2 Alabama, Act 90-203. Acts of Alabama, March 29, 1990. GATORGIRLROCKS.COM GATORGIRLROCKS.COM 3 Alabama, Act 67-503, Acts of Alabama, September 7, 1967. 4 Alabama, Act 84-66, Acts of Alabama, 1984. 5 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 6 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 7 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. ©Gator Girl Rocks (2012) – All Rights Reserved GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Smilodon californicus Serpentine Benitoite Native Gold CALIFORNIA 8 9 10 [saber-tooth cat] 1965 1985 1965 11 1973 Stegosaurus stenops Yule Marble Aquamarine Rhodochrosite COLORADO [dinosaur] 200412 197113 200214 198215 STATE ROCKS STATE Garnet Eubrontes Giganteus – CONNECTICUT [almandine garnet] [dinosaur tracks] 197716 1991 8 California Gov. Code § 425.2. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. 1) was signed by Govenor Brown on April 20, 1965. California designated the very first official state rock with this legislation (which also created the first official state mineral). 9 California State Legislature October 1, 1985. 10 California Gov. Code § 425.1. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. -

Symbols of Missouri Have You Seen?

Show-Me Symbols Missouri was named for an Algonquian Indian word that means "river of the big canoes." The state nickname is the Show-Me State and there are many natural symbols that “show us” about Missouri. The official animal of Missouri is the Missouri Mule. The mule is a hybrid between a horse (the mom) and a donkey (the dad). The mule possesses the sobriety, patience, endurance and sure-footedness of the donkey, and the vigor, strength and courage of the horse. One of the first mule breeders in the United States was George Washington. Mules are still part of the modern world; teams were used to string fiber optic cable in Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky and Tennessee. Missouri is a mining state and we have both a state rock and a state mineral. The rock is Mozarkite, a type of jasper used for building and for jewelry. Galena, the Lakeside Nature Center 4701 E Gregory, KCMO 64132 816-513-8960 www.lakesidenaturecenter.org state mineral, is the major source of lead ore. Mining of galena has flourished since the first settlers arrived and our state produces most of the nation’s lead. The American Bullfrog is the largest frog native to Missouri and is found all across the state. You can hear its deep, resonant ‘jug-of-rum’ call on warm, rainy nights between mid-May and early July. The idea for the bullfrog designation came from a fourth grade class at Chinn Elementary School in Kansas City. A group of Lee’s Summit school students worked through the legislative process to make the crinoid the state fossil of Missouri. -

From the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Kanguk Formation of Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut, Canada, and Its Ecological and Geographical Implications MATTHEW J

ARCTIC VOL. 67, NO. 1 (MARCH 2014) P. 1 – 9 A Hadrosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) Kanguk Formation of Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut, Canada, and Its Ecological and Geographical Implications MATTHEW J. VAVREK,1 LEN V. HILLS2 and PHILIP J. CURRIE3 (Received 1 October 2012; accepted in revised form 30 May 2013) ABSTRACT. A hadrosaurid vertebra was recovered during a palynological survey of the Upper Cretaceous Kanguk Formation in the eastern Canadian Arctic. This vertebra represents the farthest north record of any non-avian dinosaur to date. Although highly abraded, the fossil nonetheless represents an interesting biogeographic data point. During the Campanian, when this vertebra was deposited, the eastern Canadian Arctic was likely isolated both from western North America by the Western Interior Seaway and from more southern regions of eastern North America by the Hudson Seaway. This fossil suggests that large-bodied hadrosaurid dinosaurs may have inhabited a large polar insular landmass during the Late Cretaceous, where they would have lived year-round, unable to migrate to more southern regions during winters. It is possible that the resident herbivorous dinosaurs could have fed on non-deciduous conifers, as well as other woody twigs and stems, during the long, dark winter months when most deciduous plant species had lost their leaves. Key words: Appalachia, Arctic, Campanian, dinosaur, Laramidia, palaeobiogeography RÉSUMÉ. La vertèbre d’un hadrosauridé a été retrouvée pendant l’étude palynologique de la formation Kanguk remontant au Crétacé supérieur, dans l’est de l’Arctique canadien. Il s’agit de la vertèbre appartenant à un dinosaure non avien qui a été recueillie la plus au nord jusqu’à maintenant. -

Late Pleistocene Birds from Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Southern Appalachian Mountains, Georgia

Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. (2005) 45(4):231-248 231 LATE PLEISTOCENE BIRDS FROM KINGSTON SALTPETER CAVE, SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN MOUNTAINS, GEORGIA David W. Steadman1 Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Bartow County, Georgia, has produced late Quaternary fossils of 38 taxa of birds. The presence of extinct species of mammals, and three radiocarbon dates on mammalian bone collagen ranging from approximately 15,000 to 12,000 Cal B.P., indicate a late Pleistocene age for this fauna, although a small portion of the fossils may be Holocene in age. The birds are dominated by forest or woodland species, especially the Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) and Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). Species indicative of brushy or edge habitats, wetlands, and grasslands also are present. They include the Greater Prairie Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido, a grassland indicator) and Black-billed Magpie (Pica pica, characteristic of woody edges bordering grasslands). Both of these species reside today no closer than 1000+ km to the west (mainly northwest) of Georgia. An enigmatic owl, perhaps extinct and undescribed, is represented by two juvenile tarsometatarsi. The avifauna of Kingston Saltpeter Cave suggests that deciduous or mixed deciduous/coniferous forests and woodlands were the dominant habitats in the late Pleistocene of southernmost Appalachia, with wetlands and grasslands present as well. Key Words: Georgia; late Pleistocene; southern Appalachians; Aves; extralocal species; faunal change INTRODUCTION dates have been determined from mammal bones at Numerous late Pleistocene vertebrate faunas have been KSC. The first (10,300 ± 130 yr B.P.; Beta-12771, un- recovered from caves and other karst features of the corrected for 13C/12C; = 12,850 – 11,350 Cal B.P.) is Appalachian region (listed in Lundelius et al. -

Prootic Anatomy of a Juvenile Tyrannosauroid from New Jersey and Its Implications for the Morphology and Evolution of the Tyrannosauroid Braincase

Prootic anatomy of a juvenile tyrannosauroid from New Jersey and its implications for the morphology and evolution of the tyrannosauroid braincase Chase D Brownstein Corresp. 1 1 Collections and Exhibitions, Stamford Museum & Nature Center, Stamford, Connecticut, United States Corresponding Author: Chase D Brownstein Email address: [email protected] Among the most recognizable theropods are the tyrannosauroids, a group of small to large carnivorous coelurosaurian dinosaurs that inhabited the majority of the northern hemisphere during the Cretaceous and came to dominate large predator niches in North American and Asian ecosystems by the end of the Mesozoic era. The clade is among the best-represented of dinosaur groups in the notoriously sparse fossil record of Appalachia, the Late Cretaceous landmass that occupied the eastern portion of North America after its formation from the transgression of the Western Interior Seaway. Here, the prootic of a juvenile tyrannosauroid collected from the middle-late Campanian Marshalltown Formation of the Atlantic Coastal Plain is described, remarkable for being the first concrete evidence of juvenile theropods in that plain during the time of the existence of Appalachia and the only portion of theropod braincase known from the landmass. Phylogenetic analysis recovers the specimen as an “intermediate” tyrannosauroid of similar grade to Dryptosaurus and Appalachiosaurus. Comparisons with the corresponding portions of other tyrannosauroid braincases suggest that the Ellisdale prootic is more similar to Turonian forms in morphology than to the derived tyrannosaurids of the Late Cretaceous, thus supporting the hypothesis that Appalachian tyrannosauroids and other vertebrates were relict forms surviving in isolation from their derived counterparts in Eurasia. -

The Distinctive Theropod Assemblage of the Ellisdale Site of New Jersey and Its Implications for North American Dinosaur Ecology and Evolution During the Cretaceous

Journal of Paleontology, 92(6), 2018, p. 1115–1129 Copyright © 2018, The Paleontological Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. 0022-3360/15/0088-0906 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2018.42 The distinctive theropod assemblage of the Ellisdale site of New Jersey and its implications for North American dinosaur ecology and evolution during the Cretaceous Chase D. Brownstein Stamford Museum and Nature Center, Stamford CT 〈[email protected]〉 Abstract.—The Cretaceous landmass of Appalachia has preserved an understudied but nevertheless important record of dinosaurs that has recently come under some attention. In the past few years, the vertebrate faunas of several Appalachian sites have been described. One such locality, the Ellisdale site of the Cretaceous Marshalltown Forma- tion of New Jersey, has produced hundreds of remains assignable to dinosaurs, including those of hadrosauroids of several size classes, indeterminate ornithopods, indeterminate theropods, the teeth, cranial, and appendicular elements of dromaeosaurids, ornithomimosaurians, and tyrannosauroids, and an extensive microvertebrate assemblage. The theropod dinosaur record of the Ellisdale site is currently the most extensive and diverse known from the Campanian of Appalachia. Study of the Ellisdale theropod specimens suggests that at -

Uppermost Campanian–Maestrichtian Strontium Isotopic, Biostratigraphic, and Sequence Stratigraphic Framework of the New Jersey Coastal Plain

Uppermost Campanian–Maestrichtian strontium isotopic, biostratigraphic, and sequence stratigraphic framework of the New Jersey Coastal Plain Peter J. Sugarman New Jersey Geological Survey, CN 427, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, and Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903 Kenneth G. Miller Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 David Bukry U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, California 94025 Mark D. Feigenson Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903 ABSTRACT boundaries elsewhere in the Atlantic Recent stratigraphic studies have concen- Coastal Plain (Owens and Gohn, 1985) and trated on the relationships between these se- Firm stratigraphic correlations are the inferred global sea-level record of Haq quences, their bounding surfaces (unconfor- needed to evaluate the global significance of et al. (1987); they support eustatic changes mities), and related sea-level changes. The unconformity bounded units (sequences). as the mechanism controlling depositional shoaling-upward sequences described by We correlate the well-developed uppermost history of this sequence. However, the latest Owens and Sohl (1969) have been related to Campanian and Maestrichtian sequences Maestrichtian record in New Jersey does recent sequence stratigraphic terminology of the New Jersey Coastal Plain to the geo- not agree with Haq et al. (1987); we at- (e.g., Van Wagoner et al., 1988) by Olsson magnetic polarity time scale (GPTS) by in- tribute this to correlation and time-scale (1991) and Sugarman et al. (1993). Glauco- tegrating Sr-isotopic stratigraphy and bio- differences near the Cretaceous/Paleogene nite beds are equivalent to the condensed stratigraphy.