Competition in Television and Digital Advertising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condamnation De Daily Motion

Edinburgh Research Explorer The silver lining in Dailymotion’s copyright cloud Citation for published version: Jondet, N 2008, 'The silver lining in Dailymotion’s copyright cloud', Juriscom.net. <http://www.juriscom.net/wp-content/documents/da20080419.pdf> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Juriscom.net Publisher Rights Statement: Copyright © Nicolas JONDET Juriscom.net, 19 avril 2008 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The silver lining in Dailymotion’s copyright cloud Nicolas Jondet Doctoral candidate at the University of Edinburgh (United Kingdom) Website and contact available @: www.french-law.net Introduction Dailymotion is a video-sharing website that enables internet users to upload and watch videos online. However, it is more than just a repository for videos as it sports features allowing participation and interaction from the internet community. Users who have opened an account with Dailymotion can upload their videos but also rate and make comments on videos of others and join groups of people sharing the same interests. -

Point of Sale Newsletter

September 2017 April 2019 POINT OF SALE Updates from Benesch’s Retail, Hospitality & Consumer Products Industry Group Media Transparency: An Update on the Status of the FBI/DOJ Investigation, Recovery Efforts and Best Practices Going Forward The number of issues and areas of inquiry resulting from the revelations set forth in the ANA/K2 Report continue to mount. As originally detailed in the Fall of last year, the FBI is actively investigating certain media buying agencies for alleged non-transparent practices and looking to the advertisers potentially defrauded to assist with its investigation. Just last week, AdAge published an article noting that the FBI has an “unredacted version” of the K2 report including names of all 41 previously unidentified sources. Moreover, certain agencies are affirmatively The evidence shows media trying to cover their tracks and/or to revise their existing contracts to either permit the questionable conduct going forward or to limit the audit rights of their advertiser clients. suppliers paying undisclosed Benesch attorneys are working closely with the forensic investigators at K2 Intelligence and auditors rebates to media buying at FirmDecisions to assist clients with investigating possible wrongdoing by their (current or former) agencies in amounts ranging media buying agencies. These efforts range from helping clients navigate the potential pitfalls involved from 1.67% to 20% of in cooperating with the active FBI investigation and ensuring that they fulfill their duties to shareholders, to securing recoveries from the agencies where appropriate. Given that non-transparent conduct can aggregate media spending. often amount to a substantial percentage of a company’s overall media spend, these claims can easily stretch in to the seven- and eight-figure range. -

Advertising and the Public Interest. a Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 074 777 EM 010 980 AUTHCR Howard, John A.; Pulbert, James TITLE Advertising and the Public Interest. A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission. INSTITUTION Federal Trade Commission, New York, N.Y. Bureau of Consumer Protection. PUB EATE Feb 73 NOTE 575p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$19.74 DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Industry; Commercial Television; Communication (Thought Transfer); Consumer Economics; Consumer Education; Federal Laws; Federal State Relationship; *Government Role; *Investigations; *Marketing; Media Research; Merchandise Information; *Publicize; Public Opinj.on; Public Relations; Radio; Television IDENTIFIERS Federal Communications Commission; *Federal Trade Commission; Food and Drug Administration ABSTRACT The advertising industry in the United States is thoroughly analyzed in this comprehensive, report. The report was prepared mostly from the transcripts of the Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) hearings on Modern Advertising Practices.' The basic structure of the industry as well as its role in marketing strategy is reviewed and*some interesting insights are exposed: The report is primarily concerned with investigating the current state of the art, being prompted mainly by the increased consumes: awareness of the nation and the FTC's own inability to set firm guidelines' for effectively and consistently dealing with the industry. The report points out how advertising does its job, and how it employs sophisticated motivational research and communications methods to reach the wide variety of audiences available. The case of self-regulation is presented with recommendationS that the FTC be particularly harsh in applying evaluation criteria tochildren's advertising. The report was prepared by an outside consulting firm. (MC) ADVERTISING AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST A Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission by John A. -

Advertising and the Creation of Exchange Value

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer November 2014 Advertising and the Creation of Exchange Value Zoe Sherman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Economic History Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Sherman, Zoe, "Advertising and the Creation of Exchange Value" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 205. https://doi.org/10.7275/5625701.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/205 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVERTISING AND THE CREATION OF EXCHANGE VALUE A Dissertation Presented by ZOE SHERMAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2014 Economics © Copyright by Zoe Sherman 2014 All Rights Reserved ADVERTISING AND THE CREATION OF EXCHANGE VALUE A Dissertation Presented by ZOE SHERMAN Approved as to style and content by: ______________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Chair ______________________________________ Michael Ash, Member ______________________________________ Judith Smith, Member ___________________________________ Michael Ash, Department Chair Economics DEDICATION Dedicated to the memory of Stephen Resnick. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have had many strokes of good fortune in my life, not least the intellectual and emotional support I have enjoyed throughout my graduate studies. Stephen Resnick, Gerald Friedman, Michael Ash, and Judith Smith were the midwives of this work. -

I INFORMING a DISTRACTED AUDIENCE: NEWS NARRATIVES

INFORMING A DISTRACTED AUDIENCE: NEWS NARRATIVES IN BREAKFAST TELEVISION Emma Copeman Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (MECO), Honours Department of Media and Communications October, 2007 i Abstract This thesis takes its lead from Baym‟s (2004) suggestion that incorporation of entertainment techniques into television news undermines its authority and credibility. To explore this question, textual analysis was conducted on the news bulletins of Australian breakfast television programs Sunrise and Today with regard to narrative features and the spread of traditional news conventions compared to entertainment techniques. This analysis was followed by a discussion of the dominant meanings produced by the news narratives of Sunrise and Today. The two programs employed similar narrative styles that largely adhered to traditional news conventions, positioning themselves as impartial and authoritative relayers of news. However, narratives of both programs also diverged from traditional news: both used entertainment conventions – with Today often abandoning the traditional Inverted Pyramid news story structure for new structures – and contained briefer stories, with references to the opinions and personal experiences of the item presenters. In some breakfast news items, the short and sometimes personal narrative structure diminished the construction of impartiality. While entertainment techniques represented a potential threat to the overall authority of the news, in this analysis, the threat was mitigated by the dominance of traditional news conventions and authority was retained. In summary, departures from traditional news narrative structure and delivery are evident in Australian breakfast television, and may partly decrease its news authority and impartiality. However, the ability of these programs to retain distracted breakfast audiences may depend on the brief, entertaining and sometimes personal nature of the news items. -

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg Interactive Channels 5145 Tropicales 225 The Weather Channel 90 Interactive Dashboard 5146 Mexicana 2 City of Las Vegas Television 230 C-SPAN 92 Interactive Games 5147 Romances 3 NBC 231 C-SPAN2 4 Clark County Television 251 TLC Digital Music Channels PrismTM Complete 5 FOX 255 Travel Channel 5101 Hit List TM 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 265 National Geographic Channel 5102 Hip Hop & R&B Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 7 Universal Sports 271 History 5103 Mix Tape 132 American Life 8 CBS 303 Disney Channel 5104 Dance/Electronica 149 G4 9 LATV 314 Nickelodeon 5105 Rap (uncensored) 153 Chiller 10 PBS 326 Cartoon Network 5106 Hip Hop Classics 157 TV One 11 V-Me 327 Boomerang 5107 Throwback Jamz 161 Sleuth 12 PBS Create 337 Sprout 5108 R&B Classics 173 GSN 13 ABC 361 Lifetime Television 5109 R&B Soul 188 BBC America 14 Mexicanal 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5110 Gospel 189 Current TV 15 Univision 364 Lifetime Real Women 5111 Reggae 195 ION 17 Telefutura 368 Oxygen 5112 Classic Rock 253 Animal Planet 18 QVC 420 QVC 5113 Retro Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 19 Home Shopping Network 422 Home Shopping Network 5114 Rock 258 Science Channel 21 My Network TV 424 ShopNBC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 25 Vegas TV 428 Jewelry Television 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 27 ESPN 451 HGTV 5117 Classic Alternative 272 Biography 28 ESPN2 453 Food Network 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 274 History International 33 CW 503 MTV 5120 Soft Rock 305 Disney XD 39 Telemundo 519 VH1 5121 Pop Hits 315 Nick Too 109 TNT 526 CMT 5122 90s 316 Nicktoons 113 TBS 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5123 80s 320 Nick Jr. -

Member Directory

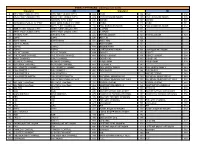

D DIRECTORY Member Directory ABOUT THE MOBILE MARKETING ASSOCIATION (MMA) Mobile Marketing Association Member Directory, Spring 2008 The Mobile Marketing Association (MMA) is the premier global non- profit association established to lead the development of mobile Mobile Marketing Association marketing and its associated technologies. The MMA is an action- 1670 Broadway, Suite 850 Denver, CO 80202 oriented organization designed to clear obstacles to market USA development, establish guidelines and best practices for sustainable growth, and evangelize the mobile channel for use by brands and Telephone: +1.303.415.2550 content providers. With more than 600 member companies, Fax: +1.303.499.0952 representing over forty-two countries, our members include agencies, [email protected] advertisers, handheld device manufacturers, carriers and operators, retailers, software providers and service providers, as well as any company focused on the potential of marketing via mobile devices. *Updated as of 31 May, 2008 The MMA is a global organization with regional branches in Asia Pacific (APAC); Europe, Middle East & Africa (EMEA); Latin America (LATAM); and North America (NA). About the MMA Member Directory The MMA Member Directory is the mobile marketing industry’s foremost resource for information on leading companies in the mobile space. It includes MMA members at the global, regional, and national levels. An online version of the Directory is available at http://www.mmaglobal.com/memberdirectory.pdf. The Directory is published twice each year. The materials found in this document are owned, held, or licensed by the Mobile Marketing Association and are available for personal, non-commercial, and educational use, provided that ownership of the materials is properly cited. -

Contact Information

THE INTERPUBLIC GROUP OF COMPANIES, INC. WORLDWIDE ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MANAGEMENT CHANGES AT INTERPUBLIC AND McCANN-ERICKSON WORLDGROUP John Dooner Returns to Lead McCann as Chairman and CEO; David Bell Named Chairman and CEO of Interpublic NEW YORK, NY (February 27, 2003) – At a regularly scheduled meeting, the Board of Directors of the Interpublic Group (NYSE: IPG) today announced significant changes in the top management of both the holding company and its largest unit, the McCann-Erickson WorldGroup. Interpublic Chairman and CEO, John J. Dooner, Jr., 54, will assume an active operating role as Chairman and CEO of McCann, replacing James R. Heekin, 53, who will be leaving the company. Mr. Dooner will retain his seat on Interpublic’s Board of Directors. David Bell, 59, will succeed Dooner as Chairman and CEO of The Interpublic Group and re-join the Board of Directors. Mr. Bell had been Vice Chairman at Interpublic since the holding company he previously headed, True North Communications, was acquired by Interpublic in 2001. Mr. Bell and Mr. Dooner will assume their new responsibilities on Thursday, February 27, 2003. According to Frank Borelli, who continues as Presiding Director of the Interpublic Board, “John’s decision is a bold one – for Interpublic to succeed, McCann must lead the way. We are very pleased that he is returning to the things he loves most: serving clients, creating great advertising and leading McCann, which John built into a global integrated marketing powerhouse during his 16-year tenure there. -

Everly IPTV Channel Guide 10-7-19.Xlsx

EVERLY IPTV BASIC (continued on back) Standard HD Standard HD 4 KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) KTIV "NBC" (SIOUX CITY) 404 CNN 104 CNN 504 9 KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) KCAU "ABC" (SIOUX CITY) 409 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 105 CNN HEADLINE NEWS 505 KDINDT2 "IPTV KIDS" 410 MSNBC 107 MSNBC 507 11 KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" KDIN IOWA PUBLIC TV "PBS" 411 CNBC 111 CNBC 511 KEYC "CBS" (MANKATO) 412 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 112 FOX BUSINESS NEWS 512 14 KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) KMEG "CBS" (SIOUX CITY) 414 C-SPAN 115 15 KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) KPTH "FOX" (SIOUX CITY) 415 C-SPAN2 116 22 KTIVDT2 "CW" KTIVDT2 "CW" 422 NICKELODEON 123 NICKELODEON 523 30 ESPN ESPN 430 NICK JR. 124 31 ESPN NEWS ESPN NEWS 431 NICK TOO 126 32 ESPN CLASSIC NICKTOONS 127 33 ESPNU ESPNU 433 BOOMERANG 129 35 ESPN2 ESPN2 435 CARTOON NETWORK 131 CARTOON NETWORK 531 39 NFL NETWORK NFL NETWORK 439 DISNEY 133 DISNEY 533 43 THE TENNIS CHANNEL THE TENNIS CHANNEL 443 DISNEY JUNIOR 134 DISNEY JUNIOR 534 44 GOLF CHANNEL GOLF CHANNEL 444 DISNEY XD 136 DISNEY XD 536 45 OLYMPIC CHANNEL OLYMPIC CHANNEL 445 FREEFORM 138 FREEFORM 538 47 OUTDOOR CHANNEL OUTDOOR CHANNEL 447 TEEN NICK 140 49 NBC SPORTS CHANNEL NBC SPORTS CHANNEL 449 DISCOVERY FAMILY 143 DISCOVERY FAMILY 543 50 FOX SPORTS 1 FOX SPORTS 1 450 DISCOVERY 144 DISCOVERY 544 51 FOX SPORTS 2 FOX SPORTS 2 451 MOTOR TREND 545 55 FOX SPORTS NORTH FOX SPORTS NORTH 455 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 149 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 549 FOX SPORTS NORTH PLUS 457 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 150 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC WILD 550 61 BIG TEN 1 (overflow) BIG TEN 1 (overflow) 461 ANIMAL PLANET 153 -

Multicasts, ATSC 3.0 Turn Broadcasting Into a Multichannel Platform

Perspectives from FSF Scholars October 12, 2020 Vol. 15, No. 53 Multicasts, ATSC 3.0 Turn Broadcasting Into a Multichannel Platform by Andrew Long * I. Introduction and Summary Consumers today enjoy a wealth of choices in the multichannel video programming distribution marketplace. This vibrantly competitive environment represents a dramatic departure from decades past, when claims as to the existence of bottlenecks were used to justify intrusive government intervention. One rising, and perhaps unexpected and largely unreported, source of multichannel competition is over-the-air broadcasting. Of course, dramatic changes in the media marketplace have been occurring for many years – and yet, due to its size, procedures, and inherent inertia, the "Communications Regulatory Complex" simply is unable to keep pace, especially in the face of considerable reflexive opposition by those who oppose any deregulatory changes. But with regard to broadcasting, cable, direct broadcast satellite (DBS), telco TV, and other media outlets, continued imposition of legacy regulatory restrictions of various types are in increasing tension with their First Amendment rights. Over the last ten years, the number of U.S. households that utilize an antenna to view their local television stations has increased by over a third, from nearly 11.8 million to 16 million. One explanation for that is the improved picture and audio quality that digital television (DTV) The Free State Foundation P.O. Box 60680, Potomac, MD 20859 [email protected] www.freestatefoundation.org delivers. Another is that, as consumers "cut the cord" – that is, discontinue their subscriptions to traditional multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs) and transition to streaming options like Netflix, Hulu, Disney+, and/or Amazon Prime Video – over-the-air television provides a free means to continue to receive the popular content, both national and local, that television stations carry. -

A Guide to Media Planning and Buying in 2021

A Guide to Media Planning and Buying in 2021 www.mediatool.com 0 1 What's included? The ‘buckle up’ mantra won’t take you far in the new normal. Whether you’re an in- house marketer or an agency media planner, adapting to the new advertising climate is crucial. More than that, reinventing your digital marketing planning to be able to mirror consumers’ ever-evolving needs will be on every marketing leader’s agenda in 2021. If you’re looking for better ways to drive traffic, generate leads and deliver more ROI, start by leaving the old tactics behind. Table of contents 02 What is media planning? 03 Media planning vs. Media buying: what’s the difference? 06 The effects of COVID-19 on media planning 09 Your step by step guide to media planning 12 Media planning challenges 17 What's next? 0 2 What is media planning? Let’s get the semantics out of the way. Media planning refers to the process of identifying, assessing, and selecting media channels and platforms to reach a well-defined target audience. Media planners determine how, where, when, and why a business will share media content to boost awareness, reach, engagement, and drive ROI through paid advertising. A media planner is responsible for developing a coordinated media plan for a given advertising budget. The more that budget is optimized – or stretched, as they like to say in the media world – to reach the largest audience for the lowest cost, the more ROI can be generated. The sole purpose of media planning is to get a brand in front of the right audience at the right time and persuade them to purchase a product or service. -

Why We Watch Television 2 Foreword

Why we watch television 2 Foreword Television is facing Sony has a long tradition of But now, in the era of connected unprecedented leading and supporting the television and online video industry through transformation available on demand, it’s disruptive change. and technology innovation. possible to focus on the needs of the individual viewer. This report provides a personal Companies are placing big view to help inform the way we We’re all individuals, with different bets on new forms of video think about television and video. backgrounds, identities and distribution, without necessarily perspectives. understanding why people might It aims to address the apparently want to watch. simple question of why we watch We all have our own reasons for television. watching television and they vary There’s a popular perception that according to the viewing context. the traditional model of television It considers what we mean by is broken, but it’s far from clear television, what television means By studying the fundamental how it will be replaced. to us and how that might evolve. psychology and sociology of our behaviours as human beings, we To understand this transformation Television has typically provided can better understand why we of television, we really need to mass audiences with shared watch television, and how we appreciate the nature of the experiences. And it will continue may view in the future. medium, the needs it addresses to do so. and the ways it’s used. Dr William Cooper Media Consultant informitv Why we watch television 3 Contents Introduction 4 Television features 7 Television research 17 Television viewing 23 Television evolution 33 Conclusions 39 Why we watch television 4 Introduction What do we mean by The idea of television includes: These are now becoming television? absorbed into a wider domain of • The screen on which it’s video media, which can deliver generally seen many of the features we have traditionally associated with The very concept of what • The medium of broadcast, television.