S Musical Modernities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![International Current Affairs [April 2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1057/international-current-affairs-april-2010-281057.webp)

International Current Affairs [April 2010]

International Current Affairs [April 2010] • Belgium became the Europe? s first country to ban burqa. • Pakistan?? s National assembly passed a bill that takes away the President s power to dissolve parliament, dismiss a elected government and appoint the three services Chiefs. Pakistan? s parliament passes 18th amendment which was later signed by Presient cutting President? s powers. • USA and Russia signed Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty(START) that allowed a maximum of 1550 deployed overheads, about 30% lower than a limit set in 2002. The treaty was signed in the Progue Castle. • Emergency was imposed in Thailand. • Nuclear Security Summit held at Washington.It was a 47 nation summit wherein P.M. announced setting up of a global nuclear energy centre for conducting research & development of design systems that are secure, proliferation resistant & sustainable. • PM visit USA & Brazil, a two nation tour. He attended Nuclear Security Summit in USA & India- Brazil-S.Africa(IBSA) and Brazil-Russia-India-China(BRIC) summit in Brasilia (Brazil). • 16th SAARC Summit held in Bhutan in 28-29 April. The summit was held in Bhutan for the first time. It is the silver jubilee summit as SAARC has completed 25 years. The summit central theme was ??Climate Change . The summit recommended to declare 2010-2020 as the ??Decade of Intra-regional Connectivity in SAARC . The 17th SAARC summit will be held in Maldives in 2011. International Current Affairs [March 2010] • China will launch in 2011 unmammed space mode ?? Tiangong I for its future space laboratory. • US internet giant Google close its business in China. • India?? s largest telecom service provider Bharti Airtel buy Zain s Africa operations for an enterprise value of $ 10.7 billion (Rs 49000 crore). -

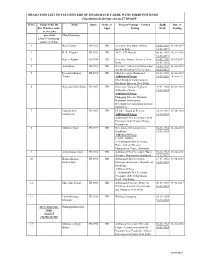

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

6Th International Folk Music Film Festival Catalogue 2016

6th International Folk Music Film Festival 24th - 26th November 2016 'Music f or Life, Music f or Survival' Coordinator:- Ram Prasad Kadel Founder, Music Museum of Nepal. Secretary:- Homenath Bhandari, Nepal International Organising Committee Ananda Das Baul, Musician and filmmaker, India. Anne Houssay, "musical instrument conservator, and research historian, at Laboratoire de recherche et de restauration du musée de la musique, Cité de la musique, Paris, France. Anne Murstad, Ethnomusicologist, singer and musician, University of Agder, Norway. Basanta Thapa, Coordinator, Kathmandu International Mountain Film Festival, (Kimff) Nepal. Charan Pradhan, Dance therapist and traditional Nepalese dancer, Scotland, UK. Claudio Perucchini, Folk song researcher Daya Ram Thapa, PABSON Nepal, Homnath Bhandari, Music Museum of Nepal. K. P. Pathaka, Film Director, Maker, Nepal Krishna Kandel, Folk Singer Mandana Cont, Architect and Poet, Iran. Meghnath, Alternative Filmmaker, Activist and teacher of filmmaking, India. Mohan Karki , Principal, Bright Future English School, Kathmandu Narayan Rayamajhi, Filmmaker and Musician, Nepal. Norma Blackstock, Music Museum of Nepal, Wales, UK. Pete Telfer: Documentary Filmmaker, Wales, UK Pirkko Moisala, Professor of Ethnomusicology, University of Helsinki, Finland. Prakash Jung Karki, Director Nepal Television, Nepal Ram Prasad Kadel, Founder, Music Museum of Nepal, Folk Music Researcher, Nepal. Rolf Killius, South Asian music and dance curator and filmmaker, UK. Steev Brown, Musician, Technical Adviser, Wales, -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

Adi-Dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi Existence In

Adi-dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi existence in relation to the environmental identity and environmental heritage of Adivasi-Moolvasi communities of Jharkhand. Sudeshna Dutta1 Abstract: Why do the Adivasis of Jharkhand resent the word Development? Since the Koel-Karo movement (Which went on for about thirty-five years) the Adivasis demanded ideal rehabilitation for them. The government officials or policymakers have so far failed to understand the meaning of the ‘ideal rehabilitation.’ In this paper, I argue that without considering the environmental identity of the Adivasi communities, it is impossible to understand the Adivasi interpretation of rehabilitation and the rationals behind such understanding. Adivasi environmental identity, I argue, has a close connection with the land, water, forest. Adivasi culture is closely related to the three elements of nature. Adivasi way of living or Adivasi way of viewing life is practice-oriented and cannot sustain without them. In this paper, I have tried to engage with the three main festivals of Jharkhand to show how the festivals carry the ethos of adi-dharam. The philosophy of Adi-dharam is about maintaining harmonious relationships with the other elements of the ecology. The rationale behind maintaining such relationship is acknowledging the contribution of others in keeping the food-security and food-sovereignty of the community. The structure of the relationships shapes the environmental identity of the Adivasi existence. The rehabilitation programmes, I conclude, need to incorporate the Adivasi interpretation of existence to protect the interest of the Adivasis. Keywords: Environmental Identity, Environmental Heritage, Adi-dharam 1 Sudeshna Dutta is a PhD fellow in the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University. -

A Report of the Workshop on Linguistic Minorities

A REPORT OF THE WORKSHOP ON LINGUISTIC MINORITIES Prof. Rajesh Sachdeva The workshop on Linguistic Minorities was organized by the Government of India, National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs in collaboration with Central Institute of Indian Languages, Ministry of Human Resource Development at Mysore on the 27 th and 28 th March 2006. While the members of the commission and its team were present on the first day, several invited speakers and members of the CIIL faculty also met on the 28 th to dwell further on the issues that had surfaced on the 27 th and also provide an opportunity to others to table their own viewpoints and experience. This report is not an attempt to resurrect the entire event with its varied discourses, although some record is maintained of chronology of speakers. It focuses more on comments /observations made in response to the terms of reference of the commission and only partly on some of the other views expressed. It also places for consideration some recommendations related to the possible follow up. 82 people participated in the event (See Appendix – 1 for the list of participants and programme) TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE COMMISSION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE WORKSHOP The terms of reference of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities were : (a) To suggest criteria for identification of socially and economically backward sections among religious and linguistic minorities. (b) To recommend measures for welfare of socially and economically backward sections among religious and linguistic minorities, including reservation in education and government employment. -

Report on Women and Water

SUMMARY Water has become the most commercial product of the 21st century. This may sound bizarre, but true. In fact, what water is to the 21st century, oil was to the 20th century. The stress on the multiple water resources is a result of a multitude of factors. On the one hand, the rapidly rising population and changing lifestyles have increased the need for fresh water. On the other hand, intense competitions among users-agriculture, industry and domestic sector is pushing the ground water table deeper. To get a bucket of drinking water is a struggle for most women in the country. The virtually dry and dead water resources have lead to acute water scarcity, affecting the socio- economic condition of the society. The drought conditions have pushed villagers to move to cities in search of jobs. Whereas women and girls are trudging still further. This time lost in fetching water can very well translate into financial gains, leading to a better life for the family. If opportunity costs were taken into account, it would be clear that in most rural areas, households are paying far more for water supply than the often-normal rates charged in urban areas. Also if this cost of fetching water which is almost equivalent to 150 million women day each year, is covered into a loss for the national exchequer it translates into a whopping 10 billion rupees per year The government has accorded the highest priority to rural drinking water for ensuring universal access as a part of policy framework to achieve the goal of reaching the unreached. -

Ias Current List-28-08-2019

GRADATION LIST OF IAS OFFICERS OF JHARKHAND CADRE WITH THEIR POSTINGS (Gradewise/Scalewise) As on 27-08-2019 Sl.No. Grade/Scale (In Name Batch Mode of Present Postings / Notified DOB Date of Rs.) Whether cadre Appt. Posting DOR Joining or ex-cadre Apex Scale Chief Secretary Level-17 in the pay matric 2.25 Lac 1 Rajiv Gauba JH-1982 RR Secretary, M/o Home Affairs, 15-08-1959 31-08-2017 Govt. of India 31-08-2019 2 B. K. Tripathi JH-1983 RR D.G., ATI, Ranchi. 08-08-1959 26-12-2018 31-08-2019 3 Rajeev Kumar JH-1984 RR Secretary, Finance Services, New 19-02-1960 01-09-2017 Delhi 28-02-2020 4 Amit Khare JH-1985 RR Secretary, Ministry of Information 14-09-1961 01-06-2018 and Broadcasting, Govt. of India 30-09-2021 5 Devendra Kumar JH-1986 RR Chief Secretary, Jharkhand 26-03-1960 31-03-2019 Tiwari Additional Charge 31-03-2020 के अपराहन से Chief Resident Commissioner, Jharkhand Bhawan, New Delhi 6 Nagendra Nath Sinha JH-1987 RR Chairman, National Highway 29-07-1964 05-03-2019 Authority of India 31-07-2024 Additional Charge Managing Director, National Highways Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) 7 Indu Shekhar JH-1987 RR Member, Board of Revenue 24-10-1962 07-06-2018 Chaturvedi Additional Charge 31-10-2022 Additional Chief Secretary, Forest, Environment & Climate Change Department 8 Sukhdeo Singh JH-1987 RR Development Commissioner, 05-03-1964 01-04-2019 Jharkhand 31-03-2024 Additional Charge 1) M.D., GRDA 2) Additional Chief Secretary, Home, Jail and Disaster Management Deptt., Jharkhand 9 Arun Kumar Singh JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, Water 07-12-1963 07-06-2018 Resource Department, Jharkhand 31.12.2023 10 Kailash Kumar JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, 27-07-1962 05-04-2019 Khandelwal Planning-cum-Finance Department, 31-07-2022 Jharkhand Additional Charge 1) Additional Chief Secretary, Personnel, A.R. -

Awards Honours 2017 Padma Vibushan

Awards Honours 2017 Important national awards for Exams: a. Highest civilian awards in chronological order 1. Bharata Ratna 2. Padma Vibushan 3. Padma Bushan 4. Padmasri 1. Bharata Ratna is the highest civilian award of India. It is instituted in 1954. The first recipients of the Bharat Ratna were politician C. Rajagopalachari, philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and scientist C. V. Raman, who were honoured in 1954 Lal Bahadur Shastri became the first individual to be honoured posthumously. Sachin Tendulkar is the youngest recipient of Bharata Ratna. He was awarded in 2014 Recent recipients- Madhan Mohan Malavay and Atal Bihari Vajpayee Two non-Indians got Bharata Ratna till now. They are Pakistan national Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and former South African President Nelson Mandela 2. Padma Vibushan is the second-highest civilian award of India. It is instituted in 1954 3. Padma Bushan is the third highest civilian award of India. It is instituted in 1954 4. Padmasri is the third highest civilian award of India. It is instituted in 1954 Padma Vibushan Awardee Field of Prominence Sharad Pawar Public Affairs Murli Manohar Joshi Public Affairs P.A. Sangma (posthumous) Public Affairs Sunder Lal Patwah (posthumous) Public Affairs K.J.Yesudas Art - Music Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev Others - Spiritualism Udipi Ramachandra Rao Science & Engineering Padma Bhushan Awardee Field of Prominence Vishwa Mohan Bhatt Art - Music Devi Prasad Dwivedi Literature & Education TehemtonUdwadia Medicine Ratna SundarMaharaj Others-Spiritualism Swami Niranjana Nanda -

Annual Return 2020 21.Pdf

KIRI INDUSTRIES LIMITED List of Shareholders As on 31.03.2021 SL FOLIO_DP_ NAME TOTAL_SHAR NO. CL_ID ES CLASS OF SHARES 1 12081800 09066984 . ANIL 15 EQUITY SHARE 2 11000011 00019887 5PAISA CAPITAL LIMITED 125 EQUITY SHARE 3 12082500 03171069 5PAISA CAPITAL LTD 2793 EQUITY SHARE 4 IN303028 74946126 A MURUGAN 100 EQUITY SHARE 5 IN302902 42346818 A POORNIMA 5 EQUITY SHARE 6 IN303028 50040956 A RAJARAMAN 902 EQUITY SHARE 7 IN301774 18813302 A AMUTHA 50 EQUITY SHARE 8 12036000 02203728 A ASHISHKUMAR . 610 EQUITY SHARE 9 12010900 11877367 A B KARTHIKEYAN . 1200 EQUITY SHARE 10 IN300513 14438886 A BABU 80 EQUITY SHARE 11 12010900 08363416 A BHAWESH KUMAR . 100 EQUITY SHARE 12 12010600 03190545 A CHAITANYA KUMAR 20 EQUITY SHARE 13 IN302269 13087726 A CHANDRAMOULEESWARAN 20 EQUITY SHARE 14 12030700 00437155 A G NARASIMHA RAO 20 EQUITY SHARE 15 IN301151 21799792 A ILANGOVAN 181 EQUITY SHARE 16 IN301356 20006929 A J SRINIVAS 9 EQUITY SHARE 17 12044700 07712603 A J YEGNESWARAN 40 EQUITY SHARE 18 IN302822 10395232 A K G SECURITIES AND CONSULTANCY LIMITED 1514 EQUITY SHARE 19 IN304295 20975809 A K VERMA 49 EQUITY SHARE 20 IN300888 13338342 A KIRAN SHETTY 100 EQUITY SHARE 21 IN301022 20825684 A KISHORE KUMAR 75 EQUITY SHARE 22 12044700 06612208 A M HONDAPPANAVAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 23 12044700 01194723 A MASTANAMMA 10 EQUITY SHARE 24 IN301151 25540407 A N J SHEIK ABDULLA 50 EQUITY SHARE 25 12076500 00121522 A NAGARATHNA 15 EQUITY SHARE 26 IN300669 10223530 A NARENDER REDDY 670 EQUITY SHARE 27 IN303077 10774003 A PADMAVATHY 50 EQUITY SHARE 28 12048800 00163502 A PL A ANNAMALAI CHETTIAR 50 EQUITY SHARE 29 IN301135 26465330 A PRANAVA 160 EQUITY SHARE 30 12010900 05675538 A PRIYA . -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations Empanelment Artists

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Sponsored by Occasion Social Media Presence Birth Empanel Category/ ICCR including Level Travel Grants 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 9/27/1961 Bharatanatyam C-52, Road No.10, 2007 Outstanding 1997-South Korea To give cultural https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Film Nagar, Jubilee Hills Myanmar Vietnam Laos performances to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ Hyderabad-500096 Combodia, coincide with the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk Cell: +91-9848016039 2002-South Africa, Establishment of an https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o +91-40-23548384 Mauritius, Zambia & India – Central https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc [email protected] Kenya American Business https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 [email protected] 2004-San Jose, Forum in Panana https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSr8A4H7VLc Panama, Tegucigalpa, and to give cultural https://www.ted.com/talks/ananda_shankar_jayant_fighti Guatemala City, Quito & performances in ng_cancer_with_dance Argentina other countries https://www.youtube.com/user/anandajayant https://www.youtube.com/user/anandasj 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 8/13/1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ -

Madurai International Documentary and Short Film Festival - a Reflection

Madurai International Documentary and Short Film Festival - A Reflection Amudhan R.P. urs is a small, local, independent, inclusive and democratic film festival. It is small because it happens in a small town like Madurai with a small team and little budget. It is local because it uses lo- Ocally available resources and people to conduct the festival. It is independent because it does not take money from big private or government institutions. It is independent in deciding the shape, content and style of the festival. It is inclusive because it does not reject films which are different in genre. It is democratic because it involves many people to select films and run the film festival. Madurai City Madurai is a small but historical town (more than two thousand years old) located in South India. It has a long history of intellectual excellence espe- cially during the Sangam period (between 3rd century BC to 2nd century AD), where poets, thinkers and leaders debated and performed in public and were appreciated by both the Kings and the common people. It is also known as temple town as there are many Hindu temples in and around the city. There are churches and mosques as well. In a way, Madurai city is an example for communal harmony as people from different religions live to- gether peacefully unlike other Indian cities. Agriculture is the main occupa- tion here apart from textile and other small scale industries. Tourism is an- other attraction here as people from within and outside India visit to enjoy the rural as well as cultural ambiance of the town.