Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution a Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused by Dr

Ten Misunderstandings About Evolution A Very Brief Guide for the Curious and the Confused By Dr. Mike Webster, Dept. of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University ([email protected]); February 2010 The current debate over evolution and “intelligent design” (ID) is being driven by a relatively small group of individuals who object to the theory of evolution for religious reasons. The debate is fueled, though, by misunderstandings on the part of the American public about what evolutionary biology is and what it says. These misunderstandings are exploited by proponents of ID, intentionally or not, and are often echoed in the media. In this booklet I briefly outline and explain 10 of the most common (and serious) misunderstandings. It is impossible to treat each point thoroughly in this limited space; I encourage you to read further on these topics and also by visiting the websites given on the resource sheet. In addition, I am happy to send a somewhat expanded version of this booklet to anybody who is interested – just send me an email to ask for one! What are the misunderstandings? 1. Evolution is progressive improvement of species Evolution, particularly human evolution, is often pictured in textbooks as a string of organisms marching in single file from “simple” organisms (usually a single celled organism or a monkey) on one side of the page and advancing to “complex” organisms on the opposite side of the page (almost invariably a human being). We have all seen this enduring image and likely have some version of it burned into our brains. -

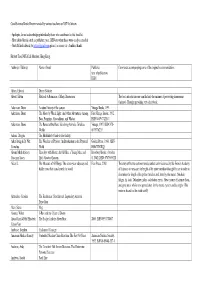

Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt229036tr No online items Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould Papers M1437 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives August 2011 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Stephen Jay Gould M1437 1 Papers M1437 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stephen Jay Gould papers creator: Gould, Stephen Jay source: Shearer, Rhonda Roland Identifier/Call Number: M1437 Physical Description: 575 Linear Feet(958 boxes) Physical Description: 1180 computer file(s)(52 megabytes) Date (inclusive): 1868-2004 Date (bulk): bulk Abstract: This collection documents the life of noted American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, Stephen Jay Gould. The papers include correspondence, juvenilia, manuscripts, subject files, teaching files, photographs, audiovisual materials, and personal and biographical materials created and compiled by Gould. Both textual and born-digital materials are represented in the collection. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Stephen Jay Gould Papers, M1437. Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Publication Rights While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use -

I Have Landed

I Have Landed IHL 1. I Have Landed ......................................................................................................... 1 IHL 2. No Science Without Fancy, No Art Without Facts: The Lepidoptery of Nabokov 3 IHL 3. Jim Bowie’s Letter and Bill Buckner’s Legs .......................................................... 4 IHL 4. The True Embodiment of Everything That’s Excellent .......................................... 6 IHL 5. Art Meets Science in The Heart of the Andes: Church Paints, Humboldt Dies, Darwin Writes, and Nature Blinks in the Fateful Year of 1859 ......................................... 7 IHL 6. The Darwinian Gentleman at Marx’s Funeral ......................................................... 9 IHL 7. The Pre-Adamite in a Nutshell .............................................................................. 11 IHL 8. Freud’s Evolutionary Fantasy ............................................................................... 13 IHL 9. The Jew and the Jewstone ..................................................................................... 16 IHL 10. When Fossils Were Young .................................................................................. 18 IHL 11. Syphilis and the Shepherd of Atlantis ................................................................. 20 IHL 12. Darwin and the Munchkins of Kansas ................................................................ 22 IHL 13. Darwin’s More Stately Mansion ......................................................................... 23 IHL 14. -

A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 61 Issue 5 Issue 5 - October 2008 Article 1 10-2008 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Scott Dodson, A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution, 61 Vanderbilt Law Review 1319 (2008) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol61/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 61 OCTOBER 2008 NUMBER 5 A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution Scott Dodson* I. INTRODU CTION ................................................................... 1320 II. THE METAPHOR OF A "LIVING" CONSTITUTION .................. 1322 III. EVALUATING THE METAPHOR ............................................. 1325 A. MetaphoricalAccuracies and Gaps ........................ 1326 B. ConstitutionalEvolution? ....................................... 1327 1. By Natural Selection ................................... 1329 2. O ther O ptions .............................................. 1333 a. Artificial Selection ............................ 1333 b. Intelligent Design ............................. 1335 c. Hybridization.................................... 1337 IV. EXTENDING THE METAPHOR .............................................. -

Cumulative Index

Stephen Jay Gould’s Essays on Natural History: A Cumulative Index Hyperlinks A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A Word of Introduction. This large file comines the indeces of all ten volumes of Stephen Jay Gould’s collections of essays reprinted from Natural History magazine. The goal is to reduce the effort to locate the reference to a particular person, item, or event; and similarly, to allow the reader to find all references to (say) Luis Alvarez in all volumes in one place. The row of hyperlinks will take you directly to the beginning of each letter’s section. To see this list at all times, click on the “bookmarks” icon in Adobe (found on the upper left of the screen). The file itself is also searchable, so you may seek the key word of your interest directly. As with all of these tasks, the identifying nomenclature is given as three or four letters followed by a number. The letters identify the volume; ESD refers to “Ever Since Darwin,” for example. (The entire sequence is listed below, in chronological order.) Similarly, the number refers to the order in which the essay appears in that volume, following Gould’s own numbering scheme. For ease of identification, I include the essay’s title as well. ESD: Ever Since Darwin. TPT: The Panda’s Thumb. HTHT: Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes. TFS: The Flamingo’s Smile. BFB: Bully for Brontosaurus. ELP: Eight Little Piggies. -

Good Science Books Recommended by Various Teachers on NSTA's Listserv

Good Science Books Recommended by various teachers on NSTA’s listserv - Apologies for not acknowledging individually those who contributed to this book list. - Have added details such as publisher, year, ISBN etc when these were easily accessible - Grateful for feedback (to [email protected] please) re errors etc. A million thanks. Herbert Tsoi, NSTA Life Member, Hong Kong. Author(s) / Editor(s) Name of book Publisher, Comments accompanying some of the original recommendations year of publication, ISBN Abbey, Edward Desert Solitaire Abbott, Edwin Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions The best introduction one can find into the manner of perceiving dimensions (Asimov). Thought provoking very short book. Ackerman, Diane A natural history of the senses Vintage Books, 1991. Ackerman, Diane The Moon by Whale Light: And Other Adventures Among First Vintage Books, 1992. Bats, Penguins, Crocodilians, and Whales ISBN 0-679-74226-3 Ackerman, Diane The Rarest of the Rare: Vanishing Animals, Timeless Vintage, 1997. ISBN 978- Worlds 0679776239 Adams, Douglas The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Adler, Irving & De Witt, The Wonders of Physics: An Introduction to the Physical Golden Press, 1966. ASIN Cornelius World B0007DVHGQ Albom, Mitch & Stacy Tuesdays with Morrie: An Old Man, a Young Man, and Broadway Books; (October Creamer, Stacy Life's Greatest Lesson. 8, 2002) ISBN: 076790592X Alder, K. The Measure of All Things: The seven-year odyssey and Free Press, 2002. The story of the two astronomers/scientists commissioned by the French Academy hidden error that transformed the world of Sciences to measure the length of the prime meridian through France in order to determine the length of the prime meridian and, thereby, the meter. -

The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister's Pox: Mending the Gap

the HEDGEHOG, the FOX, and the MAGISTER’S POX [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] the HEDGEHOG, [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] MENDING THE GAP BETWEEN SCIENCE AND THE HUMANITIES the FOX, and the MAGISTER’S POX [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] STEPHEN JAY GOULD The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, England 2011 Copyright © 2003 by Turbo, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2003 by Leslie Meredith All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by arrangement with Harmony Books, an imprint of The Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. First Harvard University Press edition, 2011. Design by Lynne Amft Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Stephen Jay. The hedgehog, the fox, and the magister’s pox : mending the gap between science and the humanities / Stephen Jay Gould. — 1st Harvard University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Harmony Books, c2003. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-06166-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Science—Social aspects. 2. Science and state. I. Title. Q175.5 .G69 2011 303.48’3—dc21 2011017925 For the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a truly exemplary organization, serving so well as the “offi- cial” voice of professional science here and elsewhere. With thanks for allowing me to serve as their president and then chairman of the board during the millennial transition of 1999–2001. This book began as my presidential address in 2000. -

Thesis Master Copy

FEAR AND LOATHING IN ACADEMIA: CHALLENGING THE DIVIDE BETWEEN SCIENCE AND THE HUMANITIES IN THE MODERN UNIVERSITY by Lauren Jeanne DeGraffenreid A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2010 © COPYRIGHT by Lauren Jeanne DeGraffenreid 2010 All Rights Reserved iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Lauren Jeanne DeGraffenreid April 2010 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TWO: “BACK OFF MAN, I’M A SCIENTIST!” WHY I CHOSE TO TOUCH THIS SUBJECT WITH CONSIDERABLY LESS THAN A TEN FOOT POLE........................1 2. WHAT WE HAVE HERE...IS A FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE”: A BRIEF HISTORY OF AN INTERNECINE CONFLICT.............................................................29 3. QUE SAIS JE? STEPHEN JAY GOULD AND THE HUMANISTIC FIELD TRIP FOR SCIENCE.........................................................................................................................55 4. STOP COCKBLOCKING ME: GOULD, WILSON, AND THE FOXY REDHEAD AT THE END OF THE BAR.................................................................................................72 5. THE FORMLESS, MUTE, INFANT, AND TERRIFYING FORM OF MONSTROSITY: THE BIRTH OF PHILOSOPHY, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE RHETORIC OF SCIENCE.......................................................................................................................100 6.