The BEAT, Volume 22, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

EINZELHANDEL NEUHEITEN-KATALOG NR. 129 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10" & 12"/7"/Dvds/Books) D-48159 MÜNSTER KONTO NR

IRIE RECORDS GMBH IRIE RECORDS GMBH BANKVERBINDUNGEN: EINZELHANDEL NEUHEITEN-KATALOG NR. 129 RINSCHEWEG 26 IRIE RECORDS GMBH (CD/LP/10" & 12"/7"/DVDs/Books) D-48159 MÜNSTER KONTO NR. 31360-469, BLZ 440 100 46 (VOM 27.07.2003 BIS 08.08.2003) GERMANY POSTBANK NL DORTMUND TEL. 0251-45106 KONTO NR. 35 60 55, BLZ 400 501 50 SCHUTZGEBÜHR: 0,50 EUR (+ PORTO) FAX. 0251-42675 SPARKASSE MÜNSTERLAND OST EMAIL: [email protected] HOMEPAGE: www.irie-records.de GESCHÄFTSFÜHRER: K.E. WEISS/SITZ: MÜNSTER/HRB 3638 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IRIE RECORDS GMBH: DISTRIBUTION - WHOLESALE - RETAIL - MAIL ORDER - SHOP - YOUR SPECIALIST IN REGGAE & SKA -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- GESCHÄFTSZEITEN: MONTAG/DIENSTAG/MITTWOCH/DONNERSTAG/FREITAG 13 – 19 UHR; SAMSTAG 12 – 16 UHR ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ *** CDs *** ALPHA BLONDY...................... PARIS BERCY................... EMI............ (FRA) (00/01). 19.99EUR GLADSTONE ANDERSON & THE MUDIE ALL STARS........................ GLADY UNLIMITED............... MOODISC........ (USA) (77/99). 21.99EUR HORACE ANDY....................... FEEL GOOD ALL OVER: ANTHOLOGY. TROJAN......... (USA) (--/02). 21.99EUR 2CD BADAWI............................ SOLDIER OF MIDIAN............. ROIR........... (USA) (01/01). 21.99EUR BEENIE MAN/BUJU BANTON/BOUNTY KILLER.......................... -

Lyrics and the Law : the Constitution of Law in Music

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2006 Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music. Aaron R. S., Lorenz University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Lorenz, Aaron R. S.,, "Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music." (2006). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2399. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2399 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2006 Department of Political Science © Copyright by Aaron R.S. Lorenz 2006 All Rights Reserved LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Approved as to style and content by: Sheldon Goldman, Member DEDICATION To Martin and Malcolm, Bob and Peter. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been a culmination of many years of guidance and assistance by friends, family, and colleagues. I owe great thanks to many academics in both the Political Science and Legal Studies fields. Graduate students in Political Science have helped me develop a deeper understanding of public law and made valuable comments on various parts of this work. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology (2005): Mutabaruka

Coping with Babylon: The Proper Rastology (2005): Mutabaruka, Half P... http://www.popmatters.com/pm/film/reviews/50538/coping-with-babylo... CALL FOR PAPERS: PopMatters seeks feature essays about any aspect of popular culture, present or past. Coping with Babylon: The Proper Rastology Director: Oliver Hill Cast: Mutabaruka, Half Pint, Luciano, Freddie McGregor, Barry Chevannes (2005) Rated: Unrated US DVD release date: 7 October 2007 (MVD) by Matthew Kantor Burning All Illusion Tonight Rastafari is known to the world through reggae music. Many interviewees in Oliver Hill’s Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology, who live Rastafari in their daily lives, cite Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Dennis Brown in particular as ambassadors of Jamaica’s great folk religion, never seeking to diminish these musicians’ roles in spreading the word. Rastafarian imagery has infiltrated popular culture not just through reggae and other kindred music, but also in the form of clothing, fashion, and general iconography. Despite the well-established co-option of the religion’s trappings and the tremendous popularity of many reggae, dub, and dancehall artists, Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology takes a sober, relatively non-musical path in broadcasting the views and roles of Rastafari in the early twenty-first century. Musicians including Luciano and Freddie McGregor are interviewed but so are leaders of various Rastafarian sects in addition to everyday followers of the faith in both Jamaica and New York. The film serves to remind viewers that Rastafarianism is a religion that deeply affects its practitioners and that music is only one aspect of it. And, like most religions, different sects vary in some of their more significant approaches and practices. -

Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health Jake Wumkes University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the African Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wumkes, Jake, "Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8311 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mystic Medicine: Afro-Jamaican Religio-Cultural Epistemology and the Decolonization of Health by Jake Wumkes A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies Department of School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Tori Lockler, Ph.D. Omotayo Jolaosho, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 27, 2020 Keywords: Healing, Rastafari, Coloniality, Caribbean, Holism, Collectivism Copyright © 2020, Jake Wumkes Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr. -

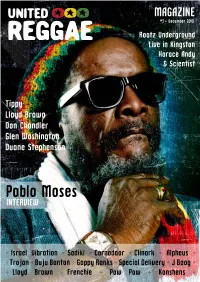

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

The Dub Issue 29 October 2018

1 Burning Spear by Ras Haile Mecael. Contact Ras Haile Mecael on Facebook or via the Art of Rastafari group on Facebook for other heart works. 2 Editorial Dub Cover photo – Instrument Of Jah mandala, Dubshack tent, One Love Festival 2018. Painting on slate by Mystys Myth, photo by Dan-I Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 28 for the month of Dan. Firstly, apologies to our regular writer Eric Denham, whose Alton Ellis piece should have appeared in the singer’s birth month of September. Afrikan History Season swings into full gear this month in Oxfordshire, with the opening of the Windrush Years exhibition at the Museum of Oxford and the conference on the legacies of Emperor Haile Selassie I. A huge thank you to the organisers of the One Love Festival and all the artists and performers for making us feel truly welcome. I hope the reviews do the event justice. As for local events, Reggae On Tap goes from strength to strength and new venture Enjoy Yourself starts this month at The Swan in Eynsham on a regular basis thanks to long time The Dub contributor Richie Roots. Finally a big thank you to Prince Jamo and Messenger Douglas for a pair of fantastic interviews, tune in next month for the first in our Tales From Birmingham. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free every month at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. While this allows for artistic freedom, it also means that money for printing is very limited. -

Freddie Mckay I'm a Free Man / Hap Ki Do Mp3, Flac, Wma

Freddie McKay I'm A Free Man / Hap Ki Do mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: I'm A Free Man / Hap Ki Do Country: UK Released: 2018 Style: Dub, Roots Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1706 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1713 mb WMA version RAR size: 1476 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 428 Other Formats: WAV MPC FLAC MIDI MMF ASF WMA Tracklist A1 –Freddie McKay I'm A Free Man A2 –Leonard Santic All Stars Santic Special (Version One) A3 –Leonard Santic All Stars Santic Special (Version Two) B1 –Augustus Pablo Hap Ki Do B2 –Augustus Pablo Hap Ki Do (Version) Credits Legal [Licensed From] – Leonard "Santic" Chin Notes 12 inch test press of 10inch re-issue (remastered) of 2005 release (Thus approximately 1 inch of vinyl is blank around edge of disc) 10 copies only manufactured of the test press 1973 (I'm A Free Man) and 1974 (Hap Ki Do) recordings Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout A, stamped): 23850 2A PST 104 Matrix / Runout (Runout B, stamped): 23850 1B PSTI 04 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Freddie McKay / Freddie McKay Santic, none, Augustus Pablo - I'm A none, / Augustus Pressure UK 2005 PST1004 Free Man / Hap Ki Do PST1004 Pablo Sounds (10") Related Music albums to I'm A Free Man / Hap Ki Do by Freddie McKay Augustus Pablo, Herman - East Of The River Nile Lorna "G", Augustus Pablo - Ooh Baby / Brixton Special Augustus Pablo / Pablo Allstars - Pablo's Theme Song / Tubb's Dub Song Various - Down Santic Way Augustus Pablo - Unfinished Dub Augustus Pablo - Pablo No Jester Augustus Pablo - Born To Dub You Part 1. -

Anti-Blues Music, Dub and Racial Identity

Dub is the new black: modes of identification and tendencies of appropriation in late 1970s post-punk Article (Accepted Version) Haddon, Mimi (2017) Dub is the new black: modes of identification and tendencies of appropriation in late 1970s post-punk. Popular Music, 36 (2). pp. 283-301. ISSN 0261-1430 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/67704/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk 1 Mimi Haddon 29.01.2016 ‘Dub is the new black: modes of identification and tendencies of appropriation in late 1970s post-punk’ Abstract This article examines the complex racial and national politics that surrounded British post-punk musicians’ incorporation of and identification with dub-reggae in the late 1970s. -

Street Hype Newspaper and Its Publishers

Patriece B. Miller Funeral Service, Inc. Licensed Funeral Director From Westmoreland, Jamaica WI • Shipping Local & Overseas ‘Community Lifestyle Newspaper’ 914-310-4294 Vol: 8 No. 09 WWW.STREETHYPENEWSPAPER.COM • FREE COPY MAY 1-18, 2013 Court Restrains Pastor By Shirley Irons, Contributing Writer he Bronx Supreme Court has intervened in the ongoing Ttwo-year financial dispute between the Board of Trustees and Pastor Ivan Plummer of the Emmannuel Seventh Day Church Ministries in the Bronx. According to court docu- titles of the ments obtained by Street Hype, church's real or the Board of Trustees and the personal proper- Happy members alleged that Plummer ties to anyone. with the help of other church The court also officers misappropriated and decided that embezzled church funds and had Plummer acted C a r i b b e a n taken over sole control of all the unilaterally Mother’s Day Pastor Ivan church assets. Plummer when he entered See Page 11 & 13 Flavor The members also claimed into the agree- Rasta Pasta that Plummer had entered into an ment on behalf of the church and agreement with an “associate” on declared that agreement null and Jerk Chicken behalf of the church without con- void. Curry Coconut Salmon sulting the trustees and he had He was further ordered to Brown Stew Salmom refused to provide a financial present a written financial Run Down Snapper accounting of the church's assets accounting of the church's assets and funds with an estimated to the members and to comply by Jerk Salmon value of nearly $1 million.