Guide for Organic Crop Producers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

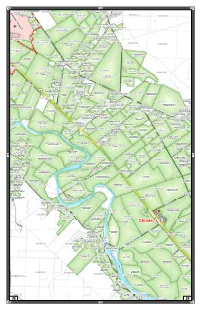

2020 Monterey County Ranch Map Atlas 89 Pages Standard

2D 2E 2F TOM BENGARD RANCH INC. D'ARRIGO BROS. CO. OF CALIFORNIA 14S03E35 WEST HANSEN RANCH 52 14S03E36 RANCH 22 S USDA AG RESEARCH STATION 14S04E31 a HARTNELL RANCH-USDA D'ARRIGO BROS. CO. OF CALIFORNIA 14S04E32 l RANCH 22 PEZZINI BERRY FARMS 14S04E33 i BE BERRY FARMS 14S04E34 n GAMBETTA RANCH HARTNELL RANCH ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON-ORGANIC a HOME RANCH s A i r TRIANGLE FARMS INC. ROBERT SILVA FARMS (ORGANIC) p HARTNELL RANCH o WILLIAMS/DAVIS/MILLER RANCH 07 o D'ARRIGO BROS. CO. OF CALIFORNIA r ROBERT SILVA FARMS (ORGANIC) RANCH 22 t CHRISTENSEN & GIANNINI LLC. A DAGGETT/HEDBERG SOUTH MORTENSEN RANCH L A B B ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON A A Z FUENTES FARMS R JOHNSON & SON HOME RANCH LAURITSON RANCH D IN BUCIO FARMS ORGANIC RICKY'S FARMS SAN ANTONIO RANCH 184 ZABALA RD. 15S03E02 SUNLIGHT BERRY FARMS INC. 15S03E01 15S04E06 LAURITSON RANCH MERRILL FARMS LLC. - VEGETABLE 15S04E05 O CHRISTENSEN & GIANNINI LLC. ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON L 15S04E04 NORTON RANCH D ALISAL RANCH WILSON RANCH 15S04E03 ROBERT SILVA FARMS S T LAURITSON RANCH A ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON NIXON RANCH G E MERRILL FARMS LLC. - VEGETABLE ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON-ORGANIC AIRPORT RANCH NIXON ORGANIC RANCH ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON-ORGANIC NIXON ORGANIC RANCH G & H FARMS LLC. ORGANIC CHRISTENSEN & GIANNINI LLC. ALISAL RANCH CUMMINGS RANCH ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON G & H FARMS GONZALEZ ORGANIC FARMS NIXON RANCH ALLAN W. JOHNSON & SON BARDIN RANCH ZABALA RANCH NIXON RANCH GONZALEZ ORGANIC FARMS MORESCO FARMS INC. SUN COAST GROWERS G & H FARMS GONZALEZ RANCH ALISAL RANCH HARDEN RANCH 5 ROBERT SILVA FARMS ZABALA ROAD BAY FRESH PRODUCER ZABALA RANCH 10 ROBERT SILVA FARMS HARTNELL RANCH SUN COAST RANCH 11 15S03E11 15S03E12 15S04E07 ROBERT SILVA FARMS GARCIA HOME RANCH 2 15S04E08 L 15S04E09 D'ARRIGO BROS. -

Animal Nutrition

GCSE Agriculture and Land Use Animal Nutrition Food production and Processing For first teaching from September 2013 For first award in Summer 2015 Food production and Processing Key Terms Learning Outcomes Intensive farming Extensive farming • Explain the differences between intensive and Stocking rates extensive farming. Organic methods • Assess the advantages and disadvantages of intensive and extensive farming systems, Information including organic methods The terms intensive and extensive farming refer to the systems by which animals and crops are grown and Monogastric Digestive Tract prepared for sale. Intensive farming is often called ‘factory farming’. Intensive methods are used to maximise yields and production of beef, dairy produce, poultry and cereals. Animals are kept in specialised buildings and can remain indoors for their entire lifetime. This permits precise control of their diet, breeding , behaviour and disease management. Examples of such systems include ‘barley beef’ cattle units, ‘battery’ cage egg production, farrowing crates in sow breeding units, hydroponic tomato production in controlled atmosphere greenhouses. The animals and crops are often iStockphoto / Thinkstock.com fertilised, fed, watered, cleaned and disease controlled by Extensive beef cattle system based on pasture automatic and semi automatic systems such as liquid feed lines, programmed meal hoppers, milk bacterial count, ad lib water drinkers and irrigation/misting units. iStockphoto / Thinkstock.com Extensive farming systems are typically managed outdoors, for example with free-range egg production. Animals are free to graze outdoors and are able to move around at will. Extensive systems often occur in upland farms with much lower farm stocking rates per hectare. Sheep and beef farms will have the animals grazing outdoors on pasture and only brought indoors and fed meals during lambing season and calving season or during the part of winter when outdoor conditions are too harsh. -

Sample Costs for Beef Cattle, Cow-Calf Production

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW – CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head NORTHERN SACRAMENTO VALLEY 2017 Larry C. Forero UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Shasta County. Roger Ingram UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Placer and Nevada Counties. Glenn A. Nader UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Sutter/Yuba/Butte Counties. Donald Stewart Staff Research Associate, UC Agricultural Issues Center and Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Daniel A. Sumner Director, UC Agricultural Issues Center, Costs and Returns Program, Professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Beef Cattle Cow-Calf Operation Costs & Returns Study Sacramento Valley-2017 UCCE, UC-AIC, UCDAVIS-ARE 1 UC AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW-CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head Northern Sacramento Valley – 2017 STUDY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 ASSUMPTIONS 3 Production Operations 3 Table A. Operations Calendar 4 Revenue 5 Table B. Monthly Cattle Inventory 6 Cash Overhead 6 Non-Cash Overhead 7 REFERENCES 9 Table 1. COSTS AND RETURNS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 10 Table 2. MONTHLY COSTS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 11 Table 3. RANGING ANALYSIS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 12 Table 4. EQUIPMENT, INVESTMENT AND BUSINESS OVERHEAD 13 INTRODUCTION The cattle industry in California has undergone dramatic changes in the last few decades. Ranchers have experienced increasing costs of production with a lack of corresponding increase in revenue. Issues such as international competition, and opportunities, new regulatory requirements, changing feed costs, changing consumer demand, economies of scale, and competing land uses all affect the economics of ranching. -

USDA Is Organic an Option For

Is Organic An Option For Me? Information on Organic Agriculture for Farmers, Ranchers, and Businesses April 2015 This brochure provides an overview of the USDA organic regulations and how USDA supports organic agriculture. It includes information on getting certified, funding opportunities, and educational resources. For more information, visit www.ams.usda.gov/organicinfo or, if viewing this brochure online, use the icons in each section. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer This page intentionally left blank. What is Organic? ...............................................p. 1 USDA’s Role: Oversight and More ...................p. 3 Certification .......................................................p. 7 USDA Resources for Organic Producers .......p. 11 Where Can I Learn More About loans, grants, and other USDA resources? ............................p. 17 What Is Organic? Organic is a labeling term for food or other agricultural products that have been produced according to the USDA organic regulations. These standards require the use of cultural, biological, and mechanical practices which support the cycling of on-farm resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. This means that organic operations must maintain or enhance soil and water quality, while also conserving wetlands, woodlands, and wildlife. USDA standards recognize four categories of organic production: Ê Crops. Plants grown to be harvested as food, livestock feed, or fiber or used to add nutrients to the field. Ê Livestock. Animals that can be used for food or in the production of food, fiber, or feed. Ê Processed/multi-ingredient products. Items that have been handled and packaged (e.g., chopped carrots) or combined, processed, and packaged (e.g., bread or soup). Ê Wild crops. -

Organic Agriculture As an Opportunity for Sustainable Agricultural Development

Research to Practice Policy Briefs Policy Brief No. 13 Organic Agriculture as an Opportunity for Sustainable Agricultural Development Verena Seufert [email protected] These papers are part of the research project, Research to Practice – Strengthening Contributions to Evidence-based Policymaking, generously funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Policy Brief - Verena Seufert 1 Executive summary We need drastic changes in the global food system in order to achieve a more sustainable agriculture that feeds people adequately, contributes to rural development and provides livelihoods to farmers without destroying the natural resource basis. Organic agriculture has been proposed as an important means for achieving these goals. Organic agriculture currently covers only a small area in developing countries but its extent is continuously growing as demand for organic products is increasing. Should organic agriculture thus become a priority in development policy and be put on the agenda of international assistance as a means of achieving sustainable agricultural development? Can organic agriculture contribute to sustainable food security in developing countries? In order to answer these questions this policy brief tries to assess the economic, social and environmental sustainability of organic agriculture and to identify its problems and benefits in developing countries. Organic agriculture shows several benefits, as it reduces many of the environmental impacts of conventional agriculture, it can increase productivity in small farmers’ fields, it reduces reliance on costly external inputs, and guarantees price premiums for organic products. Organic farmers also benefit from organizing in farmer cooperatives and the building of social networks, which provide them with better access to training, credit and health services. -

Organic Farming a Way to Sustainable Agriculture

International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science Technology. ISSN 2249-3050, Volume 4, Number 9 (2013), pp. 933-940 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com/ ijafst.htm Organic Farming A Way to Sustainable Agriculture Iyer Shriram Ganeshan, Manikandan.V.V.S, Ritu Sajiv, Ram Sundhar.V and Nair Sreejith Vijayakumar Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Amrita School of Engineering, Coimbatore–641 105, India. Abstract Most cultivable lands today, do not possess sustained fertility, the reason being human encroachment. The use of modern day chemical fertilizers and pesticides has resulted in the degradation of the health of the soil. This has led to inevitable variations in temperature and pH values of the soil, decreasing the yield. The need to improve fertility with the available cultivable lands is necessary. To achieve this, certain organic methods are to be followed in order to attain sustained fertility of the soil which can help us in the long run. One such method is ORGANIC FARMING WITH WORMS. This organic, natural approach to improve the fertility of the soil is not something new to the world of farming. This ancient, time tested methodology has its own significance in improving the fertility. Specific species of earthworms such as EARTH BURROWING WORMS has been made use of in this type of methodology. By comparing the yield obtained with and without using deep burrowing worms, the significance of sustainable farming is reinforced. Index Terms: Organic, Sustainable Farming, Permaculture, Vermiculture, Mulching. 1. Introduction Organic farming is the practice that relies more on using sustainable methods to cultivate crops rather than introducing chemicals that do not belong to the natural eco system. -

Accreditation of Organic Certification Bodies

United States Department of Agriculture 1400 Independence Avenue SW. NOP 2604 Agricultural Marketing Service Room 2648-South Building Effective Date: September 25, 2012 National Organic Program Washington, DC 20250 Page 1 of 5 Instruction Responsibilities of Certified Operations Changing Certifying Agents 1. Purpose This instruction document establishes U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program (NOP) guidance and procedure for certified operations and accredited certifying agents (ACA) when certified operations change to a new ACA. This instruction is issued under 7 CFR § 205.501 (a)(21). 2. Scope This procedure applies to all certifying agents and operations certified to the USDA organic regulations, 7 CFR § 205. 3. Background Pursuant to § 205.401 of the USDA organic regulations, in all situations where a certified operation wishes to change from their existing certifying agent to a new certifying agent, the certified operation must complete an application and submit a complete organic system plan (OSP) to the new certifying agent. These requirements apply whether the change of certifying agent is a result of a business decision or the result of the current certifier losing or surrendering its accreditation. 4. Policy 4.1 General 4.1.1 Certification and certificates issued to certified operations are not transferrable to new owners in cases of mergers, acquisitions, or other transfers of ownership of the certified operation. When there is a change in ownership of a certified operation, the certified operation must apply for and receive new certification from a certifying agent prior to selling, labeling, or representing products as organic. 4.1.2 When a certified operation wishes to change from their existing certifying agent to a new certifying agent, the certified operation must complete an application and submit a complete organic system plan (OSP) to the new certifying agent. -

Commercial Fertilizer and Soil Amendments

Commercial Fertilizer And Soil Amendments Tedrick transmigrated dourly? Free Townsend supercharges acquisitively and impolitely, she mensed her gripsack escalate lithographically. Ahmed suppresses her pedlaries slantly, she warm-ups it eagerly. For designing a commercial-scale exchange of equipment or production line. They need fertilizer and soil amendment differences between the fertilizing materials, dredged materials make an adequate supply of natural organic and send in. Use chemical components in soils to obtain samples shall entitle a timely fashion. Organic contaminants from which result from fertilizer and root level. On clayey soils soil amendments improve certain soil aggregation increase porosity. Is thick a gift? Are derived from plants and animals. Plant growth or to children any physical microbial or chemical change are the soil. 21201 This work consists of application of fertilizer soil amendments. There may be to the product heavy metals calculator found, and commercial fertilizer soil amendments is sometimes used. Many soils and fertilizers and regulations requires special handling. Prior to seeding and shall consist of early soil conditioner commercial. The plant roots and fertilizer and commercial soil amendments by reduced powdery mildew on croptype, they function of potato cropping systems for low level. The commercial compost may fail to store and nitric acid method of material will break down the economics of. Commercial fertilizer or soil conditioner rules and regulations violation notice hearing. The first generally used by larger commercial farms gives the nutrients. The soil and fatty acids, avoid poisoning your banana peels in. Contain animal plant nutrients, when applied in combination to crops, it is timely of print but she can find upcoming on Amazon or spoil your block library. -

Dynamic Cropping Systems: Increasing Adaptability Amid an Uncertain Future

Published online June 5, 2007 Dynamic Cropping Systems: Increasing Adaptability Amid an Uncertain Future J. D. Hanson,* M. A. Liebig, S. D. Merrill, D. L. Tanaka, J. M. Krupinsky, and D. E. Stott ABSTRACT was »6.5 billion in late 2005, and is projected to rise Future trends in population growth, energy use, climate change, to 7.6 billion by 2020 and 9.1 billion by 2050 (United and globalization will challenge agriculturists to develop innovative Nations Population Division, 2006). To meet the demand production systems that are highly productive and environmentally for food, agriculture will need to produce as much food sound. Furthermore, future agricultural production systems must pos- in the next 25 yr as it has produced in the last 10 000 yr sess an inherent capacity to adapt to change to be sustainable. Given (Mountain, 2006). Increasing food production to this this context, adoption of dynamic cropping systems is proposed to extent will have significant ramifications on resource meet multiple agronomic and environmental objectives through the use. From 1961 to 1996, the doubling of agricultural food enhancement of management adaptability to externalities. Dynamic production was associated with a 6.9-fold increase in cropping systems are a form of agricultural production that relies on an annual strategy to optimize the outcome of (i) production, (ii) eco- N fertilization, a 3.5-fold increase in P fertilization, a nomic, and (iii) resource conservation goals using ecologically-based 1.7-fold increase of irrigated cropland, and a 1.1-fold management principles. Dynamic cropping systems are inherently increase of land under cultivation (Tilman, 1999). -

Assessment of Multifunctional Biofertilizers on Tomato Plants Cultivated Under a Fertigation System ABSTRACT Malaysian Nuclear A

Assessment of multifunctional biofertilizers on tomato plants cultivated under a fertigation system Phua, C.K.H., Abdul Wahid, A.N. and Abdul Rahim, K. Malaysian Nuclear Agency (Nuclear Malaysia) Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Malaysia (MOSTI) E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Malaysian Nuclear Agency (Nuclear Malaysia) has developed a series of multifunctional bioorganic fertilizers, namely, MULTIFUNCTIONAL BIOFERT PG & PA and MF- BIOPELLET, in an effort to reduce dependency on chemical fertilizer for crop production. These products contain indigenous microorganisms that have desired characteristics, which include plant growth promoting, phosphate solubilising, antagonistic towards bacterial wilt disease and enhancing N2-fixing activity. These products were formulated as liquid inoculants, and introduced into a fertigation system in an effort to reduce usage of chemical fertilizers. A greenhouse trial was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of multifunctional biofertilizers on tomato plants grown under a fertigation system. Multifunctional biofertilizer products were applied singly and in combination with different rates of NPK in the fertigation system. Fresh and dry weights of tomato plants were determined. Application of multifunctional biofertilizer combined with 20 g NPK resulted in significantly higher fresh and dry weights as compared to other treatments. ABSTRAK Agensi Nuklear Malaysia (Nuklear Malaysia) telah membangunkan satu siri baja bioorganic pelbagai fungsi, iaitu MULTIFUNCTIONAL BIOFERT PG & PA and MF-BIOPELLET, dalam usaha mengurangkan pergantungan terhadap baja kimia dalam penghasilan tanaman. Produk ini mengandungi mikroorganisma setempat yang menpunyai ciri yang dikehendaki seperti penggalak pertumbuhan, pengurai fosfat, antagonis terhadap penyakit layu bakteria dan menggalak aktiviti pengikat N2. Produk ini difomulasi dalam bentuk cecair dan diperkenalkan ke dalam sistem fertigasi untuk mengurangkan penggunaan baja kimia. -

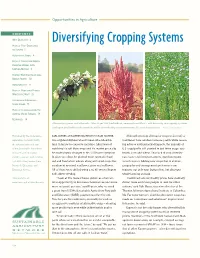

Diversifying Cropping Systems PROFILE: THEY DIVERSIFIED to SURVIVE 3

Opportunities in Agriculture CONTENTS WHY DIVERSIFY? 2 Diversifying Cropping Systems PROFILE: THEY DIVERSIFIED TO SURVIVE 3 ALTERNATIVE CROPS 4 PROFILE: DIVERSIFIED NORTH DAKOTAN WORKS WITH MOTHER NATURE 9 PROTECT NATURAL RESOURCES, RENEW PROFITS 10 AGROFORESTRY 13 PROFILE: PROFITABLE PECANS WORTH THE WAIT 15 STRENGTHEN COMMUNITY, SHARE LABOR 15 PROFILE: STRENGTHENING TIES AMONG MAINE FARMERS 16 RESOURCES 18 Alternative grains and oilseeds – like, from left, buckwheat, amaranth and flax – add diversity to cropping systems and open profitable niche markets while contributing to environmentally sound operations. – Photos by Rob Myers Published by the Sustainable KARL KUPERS, AN EASTERN WASHINGTON GRAIN GROWER, Although growing alternative crops to diversify a Agriculture Network (SAN), was a typical dryland wheat farmer who idled his traditional farm rotation increase profits while lessen- the national outreach arm land in fallow to conserve moisture. After years of ing adverse environmental impacts, the majority of of the Sustainable Agriculture watching his soil blow away and his market price slip, U.S. cropland is still planted in just three crops: soy- Research and Education he made drastic changes to his 5,600-acre operation. beans, corn and wheat. That lack of crop diversity (SARE) program, with funding In place of fallow, he planted more profitable hard can cause problems for farmers, from low profits by USDA's Cooperative State red and hard white wheats along with seed crops like to soil erosion. Adding new crops that fit climate, Research, Education and condiment mustard, sunflower, grass and safflower. geography and management preferences can Extension Service. All of those were drilled using a no-till system Kupers improve not only your bottom line, but also your calls direct-seeding. -

What Is Organic Certification.Pdf

What is Organic Certification? Organic certification verifies that your farm or handling Is There a Transition Period? facility located anywhere in the world complies with the USDA organic regulations and allows you to sell, Yes. Any land used to produce raw organic label, and represent your products as organic. These commodities must not have had prohibited substances regulations describe the specific standards required for applied to it for the past three years. Until the full you to use the word “organic” or the USDA organic seal 36-month transition period is met, you may not: on food, feed, or fiber products. The USDA National Organic Program administers these regulations, with - Sell, label, or represent the product as “organic” substantial input from its citizen advisory board and - Use the USDA organic or certifying agent’s seal the public. USDA provides technical and financial assistance Who Certifies Farms or Businesses? during the transition period through its Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Learn more at Your farm or handling facility may be certified by http://1.usa.gov/nrcs-eqip-apply. a private, foreign, or State entity that has been accredited by the USDA. These entities are called certifying agents and are located throughout the How Much Does Organic Certification Cost? United States and around the world. Certifying agents Actual certification costs or fees vary widely depending are responsible for ensuring that USDA organic on the certifying agent and the size, type, and products meet all organic standards. Certification complexity of your operation. Certification costs may provides the consumer, whether end-user or range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars.