Rcia-Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, 17 April

Tuesday, 17 April 08:00-09:00 Conference Registration Desk Open 09:00-09:30 Conference Opening - Homer Stavely, Common Ground Research Networks, Champaign, USA 09:30-10:05 Plenary Session - Susan Abraham, Pacific School of Religion, Berkeley, USA "Is Religion Relevant? The Time, Space and Law of the Nation" 10:05-10:35 Garden Conversation & Coffee Break 10:35-11:20 Talking Circles Room 1 - Religious Foundations Room 2 - Religious Community and Socialization Room 3 - Religious Commonalities and Differences Room 4 - The Politics of Religion Room 5 - 2018 Special Focus: "Religion, Spirituality, and Sociopolitical Engagement" 11:20-11:30 Transition 11:30-12:45 PARALLEL SESSIONS Room 1 Gender Impacts and Implications Gender in Transformation: The Temporary Buddhist Ordination and Women’s Empowerment in Thailand Kakanang Yavaprabhas, Literature about the issue of bhikkhuni (female Buddhist monks or fully ordained nuns), whose existence in Theravada tradition has controversially been recently revived, tends to portray the topic as more relevant to international platforms than to local communities. This study, based on ethnographic fieldwork in Thailand, however, shows that the topic of bhikkhuni is pertinent to locals and the society. In Thai society where nearly 95 percent of the population self-identifies as Buddhist, Buddhism is influential and the full Buddhist monastic status is highly prestigious. The full monastic form for women as bhikkhuni bestowed by the Buddha, however, was not locally available, and only in 2003 that the first Thai woman can controversially assume it. In 2009 the temporary ordination as female novices (samaneri), remarkably similar to the traditional temporary ordination for men, has also been publicly available and at least 1,234 Thai women received the ordination. -

150 Fils Max 36º

SUBSCRIPTION Min 19º 150 Fils Max 36º SATURDAY, APRIL 16, 2016 RAJAB 9, 1437 AH No: 16846 Idaho State Univ Egypt police fire Man City-Real, faces concerns tear gas, break up Atletico-Bayern over Islamophobia3 anti-govt8 rallies in48 CL semifinals NEWS SATURDAY, APRIL16, 2016 Islamic summit appreciates Kuwait for hosting Yemen talks Kuwait’s humanitarian support to Syrians lauded ISTANBUL: The 13th Islamic Summit was an apt tribute paid to His Highness the personality of the State of Palestine at the Great hope Conference of the Organization of Islamic Amir for his leading support to humanitarian international level. Secretary General of the Organization of Cooperation (OIC) that wrapped up meetings causes around the world. The Conference commended the efforts Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Iyad Madani said that yesterday highly appreciated Kuwait that will The Heads of State and Government of the deployed by His Majesty King Mohamed VI, the peoples of the Muslim world pin great host negotiations among Yemeni stakeholders Member States of the OIC concluded their Chairman of the Al-Quds (Jerusalem) hopes on the 13th Islamic Summit Conference. on Monday. summit dubbed ‘Unity and Solidarity for Committee to protect the Islamic and Christian The two-day summit was attended by heads of The Final Communique of the summit, Justice and Peace’ in Istanbul, Turkey. The holy sites in Jerusalem in the face of the meas- states and governments from over 30 countries. dubbed the ‘Istanbul Declaration’, also com- Summit Conference was chaired by Recep ures being taken by the Israeli occupation Madani lauded the endorsement of the OIC mended Kuwait’s support to the humanitarian Tayyip Erdogan, President of the Republic of authorities aimed and Judaizing the holy city. -

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

Optimization of Performance in Top-Level Athletes During the Kumite in Sport Karate

Journal of Sports Science 4 (2016) 132-149 D doi: 10.17265/2332-7839/2016.03.003 DAVID PUBLISHING Optimization of Performance in Top-Level Athletes during the Kumite in Sport Karate Nazim Kurtovic¹ and Nadia Savova² 1. Department of Special Physical Education, Faculty for Detectives and Security, FON University, Skopje 1000, Macedonia 2. Department of Anatomy and Biomechanics, National Sports Academy, Sofia 1000, Bulgaria Abstract: This text represents a research that by individual treatment explores the influence and effect of the so-called advanced karate training (combined training program for development of physical and mental skills) in strengthening the person’s tolerance to difficult and stressful situations. The aim of the research was to achieve optimal performance by the athletes during the kumite1 in karate. The research involved initial, control and final experiment, where the karate practitioners were focused on the training model given (group; n = 13) and working in a group with additional individual intensive sessions provided for each participant. All athletes were male contestants aged 26.4 ± 6.8. The aim of the research was to explore how their performance can be influenced using psychological techniques during karate trainings, or how not to fall into one of the four undesirable states of mind called Shikai2. Results confirmed that the model of combined physical and mental training for athletes improves their physical skills and optimizes performance during competitions. Key words: Kumite, karate, timing, mental training, optimal performance. 1. Introduction adequate moves. We believe that establishing a duly substantiated theory is extremely important for The idea behind this text is to attract the attention of practical karate and would contribute more instructors the professional karate community towards the and athletes to perceive specific activities on rational necessity of systematic approach to the training and functional level [1]. -

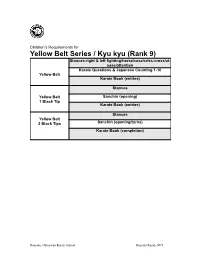

Yellow Belt Series / Kyu Kyu (Rank 9)

Children’s Requirements for Yellow Belt Series / Kyu kyu (Rank 9) Stances-right & left fighting/horse/cesa/criss-cross/at- ease/attention Karate Questions & Japanese Counting 1-10 Yellow Belt Karate Book (entries) Stances Yellow Belt Sanchin (opening) 1 Black Tip Karate Book (entries) Stances Yellow Belt 2 Black Tips Sanchin (opening/turns) Karate Book (completion) Roanoke Okinawan Karate School RoanokeKarate.NET Children’s Requirements for Orange Belt Series / Hachi kyu (Rank 8) Yellow Belt Requirements Orange Belt Sanchin (complete) Exercises (Hook Punch) Sanchin (complete) Orange Belt Kanshiwa (turn/block/punch) 1 Black Tip Exercises (Hook Punch, Front Punch) Sanchin (complete) Orange Belt Kanshiwa (forward) 2 Black Tips Exercises (Hook Punch, Front Punch) Karate Book Completion Roanoke Okinawan Karate School RoanokeKarate.NET Children’s Requirements for Purple Belt Series / Sichi kyu (Rank 7) Sanchin Purple Belt Kanshiwa (forward/backward) Exercises (Hook Punch, Front Punch, Side-foot kick) Sanchin Purple Belt 1 Black Tip Kanshiwa (complete) Exercises ( Hook Punch, Front Punch, Side-foot kick, Front Kick) Sanchin Purple Belt Kanshiwa 2 Black Tips Exercises (add 4 Knuckle block/punch, Block/chop/ back fist, shoken) Kumite 1 (sequence) Karate Book Completion Roanoke Okinawan Karate School RoanokeKarate.NET Children’s Requirements for Blue Belt Series/Advanced Sichi kyu (Rank 7) Sanchin Kanshiwa Blue Belt All Exercises Kumite 1 (proficient) Sanchin Blue Belt 1 Black Tip Kanshiwa Kanshiwa Bunkai (open) & All Exercises Kumite 2 (sequence) -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Die Riten Des Yoshida Shinto

KAPITEL 5 Die Riten des Yoshida Shinto Das Ritualwesen war das am eifersüchtigsten gehütete Geheimnis des Yoshida Shinto, sein wichtigstes Kapital. Nur Auserwählte durften an Yoshida Riten teilhaben oder gar so weit eingeweiht werden, daß sie selbst in der Lage waren, einen Ritus abzuhalten. Diese zentrale Be- deutung hatten die Riten sicher auch schon für Kanetomos Vorfah- ren. Es ist anzunehmen, daß die Urabe, abgesehen von ihren offizi- ellen priesterlichen Aufgaben, wie sie z.B. in den Engi-shiki festgelegt sind, bereits als ietsukasa bei diversen adeligen Familien private Riten vollzogen, die sie natürlich so weit als möglich geheim halten muß- ten, um ihre priesterliche Monopolstellung halten und erblich weiter- geben zu können. Ein Austausch von geheimen, Glück, Wohlstand oder Schutz vor Krankheiten versprechenden Zeremonien gegen ge- sellschaftliche Anerkennung und materielle Privilegien zwischen den Urabe und der höheren Hofaristokratie fand sicher schon in der späten Heian-Zeit statt, wurde allerdings in der Kamakura Zeit, als das offizielle Hofzeremoniell immer stärker reduziert wurde, für den Bestand der Familie umso notwendiger. Dieser Austausch verlief offenbar über lange Zeit in sehr genau festgelegten Bahnen: Eine Handvoll mächtiger Familien, alle aus dem Stammhaus Fujiwara, dürften die einzigen gewesen sein, die in den Genuß von privaten Urabe-Riten gelangen konnten. Bis weit in die Muromachi-Zeit hin- ein existierte die Spitze der Hofgesellschaft als einziger Orientie- rungspunkt der Priesterfamilie. Mit dem Ōnin-Krieg wurde aber auch diese Grundlage in Frage gestellt, da die Mentoren der Familie selbst zu Bedürftigen wurden. Selbst der große Ichijō Kaneyoshi mußte in dieser Zeit sein Über- leben durch Anbieten seines Wissens und seiner Schriften an mächti- ge Kriegsherren wie z.B. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

Soka Education Conference

7th Annual Soka Education Conference February 19-21, 2011 7TH ANNUAL SOKA EDUCATION CONFERENCE 2011 SOKA UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA ALISO VIEJO, CALIFORNIA FEBRUARY 19TH, 20TH & 21ST, 2011 PAULING 216 Disclaimer: The content of the papers included in this volume do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Soka Education Student Research Project, the members of the Soka Education Conference Committee, or Soka University of America. The papers were selected by blind submission and based on a one page proposal. Copyrights: Unless otherwise indicated, the copyrights are equally shared between the author and the SESRP and articles may be distributed with consent of either party. The Soka Education Student Research Project (SESRP) holds the rights of the title “7th Annual Soka Education Conference.” For permission to copy a part of or the entire volume with the use of the title, SESRP must have given approval. The Soka Education Student Research Project is an autonomous organization at Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, California. Soka Education Student Research Project Soka University of America 1 University Drive Aliso Viejo, CA 92656 Office: Student Affairs #316 www.sesrp.org [email protected] Soka Education Conference 2011 Program Pauling 216 Day 1: Saturday, February 19th Time Event Personnel 10:00 – 10:15 Opening Words SUA President Danny Habuki 10:15 – 10:30 Opening Words SESRP 10:30 – 11:00 Study Committee Update SESRP Study Committee Presentation: Can Active Citizenship be 11:00 – 11:30 Dr. Namrata Sharma Learned? 11:30 – 12:30 Break Simon HØffding (c/o 2008) Nozomi Inukai (c/o 2011) 12:30 – 2:00 Symposium: Soka Education in Translation Gonzalo Obelleiro (c/o 2005) Respondents: Professor James Spady and Dr. -

(Dprk) 2017 International Religious Freedom Report

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA (DPRK) 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of religious belief. The 2014 Report of the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) on Human Rights in the DPRK, however, concluded there was an almost complete denial by the government of the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, and in many instances, violations of human rights committed by the government constituted crimes against humanity. In August the UN secretary-general and in September the special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the DPRK released reports reiterating concerns about the country’s use of arbitrary executions, political prison camps, and torture amounting to crimes against humanity. In March and December, the UN Human Rights Council and UN General Assembly plenary session, respectively, adopted resolutions by consensus that “condemned in the strongest terms the long-standing and ongoing systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations,” including denial of the right to religious freedom, and urged the government to acknowledge such violations and take immediate steps to implement relevant recommendations by the United Nations. A South Korean nongovernmental organization (NGO) said there were 1,304 cases of violations of the right to freedom of religion or belief by DPRK authorities during the year, including 119 killings and 87 disappearances. The country in the past deported, detained, and sometimes released foreigners who allegedly engaged in religious activity within its borders. Reports indicated DPRK authorities released one foreign Christian in August. According to NGOs and academics, the government’s policy toward religion was to maintain an appearance of tolerance for international audiences, while suppressing internally all religious activities not sanctioned by the state. -

Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea

ORGANIZED PERSECUTION DOCUMENTING RELIGIOUS FREEDOM VIOLATIONS IN NORTH KOREA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Organized Persecution: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea 01 USCIRF’S MISSION To advance international freedom of religion or belief, by independently assessing and unflinchingly confronting threats to this fundamental right. CHAIR Nadine Maenza VICE CHAIR Nury Turkel COMMISSIONERS Anurima Bhargava James W. Carr Frederick A. Davie Tony Perkins EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Erin D. Singshinsuk UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 02 Organized Persecution: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea CONTENTS 3 About The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 3 Who We Are 3 What Religious Freedom Is 5 Introduction 7 Organizational Structure of Religious Freedom Violations 13 Compliance, Enforcement, and the Denial of Religious Freedom 15 Denial of Religious Freedom from Birth 17 Arbitrary Arrest, Detention, and the Absence of Due Process and Fair Trial Rights 23 Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 27 Conclusions 29 About the Authors Organized Persecution: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea 1 2 Organized Persecution: Documenting Religious Freedom Violations in North Korea ABOUT THE UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM WHO WE ARE WHAT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IS The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom Inherent in religious freedom is the right to believe or not (USCIRF) is an independent, bipartisan U.S. federal believe as one’s conscience leads, and to live out one’s beliefs government commission created by the 1998 International openly, peacefully, and without fear. Freedom of religion Religious Freedom Act (IRFA). USCIRF uses international or belief is an expansive right that includes the freedoms of standards to monitor violations of religious freedom or belief thought, conscience, expression, association, and assembly.