Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

5. Organic Orchard

MucknellAbbey Factsheet #5 Organic Orchard Following the vision laid out in the Land Use Strategy for Mucknell, we are working towards producing most of our food using organic methods, contributing to income generation by selling produce. In February 2011, we planted 31 fruit trees, to form an organic orchard. We sourced most of the trees from Walcot Organic Nursery, in the Vale of Evesham, and the Banns were a gift. We planted separate stands of apples, pears and plums. Crab apples are very good pollinators of all apples, so were planted on the edge of the stand of apples to encourage pollination. We planted Gladstone on a corner, so that its vigorous rootstock is less likely to interfere with the growth of the other trees. We planted other varieties according to their pollination groups, so that Bs are next to A-Cs, Cs are next to B-Ds, etc. We are planning to plant comfrey under the trees, cutting it and leaving it in situ to rot down around the trees as a natural fertiliser. Apple (Malus) 1 Adam's Pearmain 2 Annie Elizabeth 4 C 17 8 D 3 Ashmead's Kernel 30,31 Banns 4 Bountiful 5 Blenheim Orange 1 B 5 CT 6 C 6 Discovery 7 Edward VII 8 Gladstone 9 Grenadier 10 Lord Lambourne N 10 B 2 D 11 Pitmaston Pineapple E 12 Rajka D 13 William Crump 14 Winston R A 9 C 7 E 15 Worcester Pearmain 16 Wyken Pippin G Crab Apple (Malus) 17 Harry Baker N 18 Red Sentinel 30 D Bore 3 D E Plum (Prunus) hole 19 Belle de Louvain H 20 Gage - Cambridge Gage C 21 Marjories Seedling T 31 D 13 D 22 Opal I 23 Pershore Purple K 24 Damson - Shropshire Prune Pear (Pyrus) 25 Beth 11 C 14 D 12 C 26 Beurre Hardy 27 Concorde 28 Louise Bonne of Jersey 29 Worcester Black 15 C 18 16 C 19 C 28 B 29 C 22 C 23 C 26 C 25 D 20 D About Mucknell 21 E Mucknell Abbey is a contemplative monastic community of nuns and monks living under the 27 C Rule of St Benedict and part of the Church of 24 D England. -

9–2–05 Vol. 70 No. 170 Friday Sept. 2, 2005 Pages

9–2–05 Friday Vol. 70 No. 170 Sept. 2, 2005 Pages 52283–52892 VerDate Aug 18 2005 19:41 Sep 01, 2005 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\02SEWS.LOC 02SEWS i II Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 170 / Friday, September 2, 2005 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2010 Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Meddles, Erik, "Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism" (2010). All Regis University Theses. 544. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/544 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

A Manual Key for the Identification of Apples Based on the Descriptions in Bultitude (1983)

A MANUAL KEY FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF APPLES BASED ON THE DESCRIPTIONS IN BULTITUDE (1983) Simon Clark of Northern Fruit Group and National Orchard Forum, with assistance from Quentin Cleal (NOF). This key is not definitive and is intended to enable the user to “home in” rapidly on likely varieties which should then be confirmed in one or more of the manuals that contain detailed descriptions e.g. Bunyard, Bultitude , Hogg or Sanders . The varieties in this key comprise Bultitude’s list together with some widely grown cultivars developed since Bultitude produced his book. The page numbers of Bultitude’s descriptions are included. The National Fruit Collection at Brogdale are preparing a list of “recent” varieties not included in Bultitude(1983) but which are likely to be encountered. This list should be available by late August. As soon as I receive it I will let you have copy. I will tabulate the characters of the varieties so that you can easily “slot them in to” the key. Feedback welcome, Tel: 0113 266 3235 (with answer phone), E-mail [email protected] Simon Clark, August 2005 References: Bultitude J. (1983) Apples. Macmillan Press, London Bunyard E.A. (1920) A Handbook of Hardy Fruits; Apples and Pears. John Murray, London Hogg R. (1884) The Fruit Manual. Journal of the Horticultural Office, London. Reprinted 2002 Langford Press, Wigtown. Sanders R. (1988) The English Apple. Phaidon, Oxford Each variety is categorised as belonging to one of eight broad groups. These groups are delineated using skin characteristics and usage i.e. whether cookers, (sour) or eaters (sweet). -

Community Exhibitor Survey Report 2013

Page 3 Key points 5 Executive summary 8 1 Introduction 8 1.1 Background 8 1.2 Aims 8 1.3 Timescale 8 1.4 Sector 9 2 Methods 9 2.1 Introduction 9 2.2 Responses 10 3 Results 10 3.1 Year of establishment 10 3.2 Membership 11 3.3 Admissions 13 3.4 Provision 15 3.5 Programming 16 3.6 Administration 18 3.7 The benefits of community exhibition 19 3.8 Using BFFS services and resources 20 3.9 Rating BFFS services and resources 22 Appendix 1: 2012/13 film list 27 Appendix 2: Feedback on BFFS Page 2 of 30 Community exhibition is more dynamic than ever, with greater opportunities for audiences to experience films on the big screen through community cinema events, film society activity and innovative pop-up screenings in non-traditional venues: Responding community exhibitors recorded around 213,000 admissions in 2012/13. Theatrical ticket sales on this scale would have generated box office revenues of £1.4 million. Nearly half of responding community exhibitors saw an increase in their annual admissions (46%), and 40% recorded roughly the same number as in the previous year. Three quarters (76%) of membership organisations saw their membership stay the same or increase over the last year, and average membership stood at 154. Responding community exhibitors hosted 4,175 screenings in 2012/13. Community exhibition is run for the benefit of communities, enhancing the quality of life locally, encouraging participation in cultural and communal activities and providing volunteering opportunities: The majority of responding organisations (89%) are run as not-for-profit, and 20% have charitable status. -

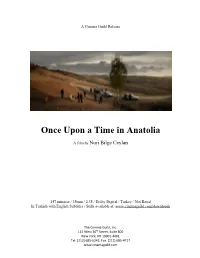

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

A Cinema Guild Release Once Upon a Time in Anatolia A film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan 157 minutes / 35mm / 2.35 / Dolby Digital / Turkey / Not Rated In Turkish with English Subtitles / Stills available at: www.cinemaguild.com/downloads The Cinema Guild, Inc. 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 New York, NY 10001‐4061 Tel: (212) 685‐6242, Fax: (212) 685‐4717 www.cinemaguild.com Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Synopsis Late one night, an array of men- a police commissioner, a prosecutor, a doctor, a murder suspect and others- pack themselves into three cars and drive through the endless Anatolian country side, searching for a body across serpentine roads and rolling hills. The suspect claims he was drunk and can’t quite remember where the body was buried; field after field, they dig but discover only dirt. As the night draws on, tensions escalate, and individual stories slowly emerge from the weary small talk of the men. Nothing here is simple, and when the body is found, the real questions begin. At once epic and intimate, Ceylan’s latest explores the twisted web of truth, and the occasional kindness of lies. About the Film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia was the recipient of the Grand Prix at the Cannes film festival in 2011. It was an official selection of New York Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Biography: Born in Bakırköy, Istanbul on 26 January 1959, Nuri Bilge Ceylan spent his childhood in Yenice, his father's hometown in the North Aegean province of Çanakkale. -

'Honey Gold' Mango Fruit

Final Report Improving consumer appeal of Honey Gold mango by reducing under skin browning and red lenticel discolouration Peter Hofman The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) Project Number: MG13016 MG13016 This project has been funded by Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited with co-investment from Piñata Farms Pty Ltd and funds from the Australian Government. Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (Hort Innovation) makes no representations and expressly disclaims all warranties (to the extent permitted by law) about the accuracy, completeness, or currency of information in Improving consumer appeal of Honey Gold mango by reducing under skin browning and red lenticel discolouration. Reliance on any information provided by Hort Innovation is entirely at your own risk. Hort Innovation is not responsible for, and will not be liable for, any loss, damage, claim, expense, cost (including legal costs) or other liability arising in any way (including from Hort Innovation or any other person’s negligence or otherwise) from your use or non-use of Improving consumer appeal of Honey Gold mango by reducing under skin browning and red lenticel discolouration, or from reliance on information contained in the material or that Hort Innovation provides to you by any other means. ISBN 978 0 7341 3977 1 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited Level 8, 1 Chifley Square Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 © Copyright 2016 Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................... -

Teaching Mission in the Complex Public Arena: Developing Missiologically Informed Models of Engagement

APM Teaching Mission in the Complex Public Arena: Developing Missiologically Informed Models of Engagement The 2017 Proceedings of The Association of Professors of Mission 2017 APM Annual Meeting, Wheaton, IL June 15-16, 2017 APM Teaching Mission in the Complex Public Arena Teaching Mission in the Complex Public Arena The 2017 Proceedings of the Association of Professors of Missions. Published by First Fruits Press, © 2018 Digital version at http://place.asburyseminary.edu/academicbooks/26/ ISBN: 9781621718130 (print), 9781621718147 (digital), 9781621718154 (kindle) First Fruits Press is publishing this content by permission from the Association of Professors of Mission. Copyright of this item remains with the Association of Professors of Mission. First Fruits Press is a digital imprint of the Asbury Theological Seminary, B.L. Fisher Library. Its publications are available for noncommercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. First Fruits Press has licensed the digital version of this work under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. For all other uses, contact Association of Professors of Missions 108 W. High St. Lexington, KY 40507 http://www.asmweb.org/content/apm Teaching Mission in the Complex Public Arena The 2017 Proceedings of the Association of Professors of Missions. 1 online resource (v, 164 pages) : digital Wilmore, Ky. : First Fruits Press, ©2018. ISBN: 9781621718147 (online.) 1. Missions – Study and teaching – Congresses. 2. Missions – Theory – Congresses. 3. Education – Philosophy – Congresses. 4. Teaching – Methodology – Congresses. I. Title. II. Danielson, Robert A. -

Holds June 25 at Eko Hotel & Suites, Victoria Island Lagos. There

Holds June 25 at Eko Hotel & Suites, Victoria Island Lagos. There are 34 beautiful contestants from different states in Nigeria. The event starts By 6pm Supple Magazine Africa's Leading Film Festivals and Movies Portal Search YEAR: 2011 2nd Eko International Film Festival, July 9 – 14, 2011 Posted on June 3, 2011 by admin — No Comments ↓ CALL FOR ENTRY 2ND EKO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL The 2nd Edition of the Eko International Film Festival (EKOIFF) will be held from 9-14 July, 2011, in Lagos, Nigeria. The different categories of film to be submitted are: Feature Length Short Films Fiction Comedy Drama Horror Documentaries Student 1 minute short films. The submission deadlines: Standard Deadline: May 30, 2011 Late Deadline: June 15, 2011 Final Deadline: June 25, 2011 Applications for submitting films to the 2nd EKOIFF will be available on the official EKOIFF. For more information, visit the official EKOIFF website www.ekoiff.com, or send e-mail to [email protected] (see link: http://www.ekoiff.com/submit.htm) Address: 1 Bajulaiye Road, Opposite Skye bank plc Shomolu, Lagos, Nigeria Tel: +2348033036171, +2347066379246. Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.ekoiff.com/ PARTNERS: Posted in Competitions, Featured, Film Festivals, Kulturati, Life & Style, News, World | Leave a reply 2011 Most Beautiful Girl in Nigeria Screening Dates Posted on May 30, 2011 by admin — No Comments ↓ The final screening dates for the 2011 Most Beautiful Girl in Nigeria (MBGN) have been announced with the locations: MBGN Screening Dates and Venues: • May 31, 2011. Royal Marble Hotel, Benin, Edo State. • June 2, 2011. Sports Cafe, Silverbird Showtime, Akwa Ibom Tropicana, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State.