Nepalese Linguistics Is a Journal Published by Linguistic Society of Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 20 Backup Bulletin Format on Going

gkfnL] nfsjftf] { tyf ;:s+ lt[ ;dfh Nepali Folklore Society Nepali Folklore Society Vol.1 December 2005 The NFS Newsletter In the first week of July 2005, the research Exploring the Gandharva group surveyed the necessary reference materials related to the Gandharvas and got the background Folklore and Folklife: At a information about this community. Besides, the project office conducted an orientation programme for the field Glance researchers before their departure to the field area. In Introduction the orientation, they were provided with the necessary technical skills for handling the equipments (like digital Under the Folklore and Folklife Study Project, we camera, video camera and the sound recording device). have completed the first 7 months of the first year. During They were also given the necessary guidelines regarding this period, intensive research works have been conducted the data collection methods and procedures. on two folk groups of Nepal: Gandharvas and Gopalis. In this connection, a brief report is presented here regarding the Field Work progress we have made as well as the achievements gained The field researchers worked for data collection in from the project in the attempt of exploring the folklore and and around Batulechaur village from the 2nd week of July folklife of the Gandharva community. The progress in the to the 1st week of October 2005 (3 months altogether). study of Gopalis will be disseminated in the next issue of The research team comprises 4 members: Prof. C.M. Newsletter. Bandhu (Team Coordinator, linguist), Mr. Kusumakar The topics that follow will highlight the progress and Neupane (folklorist), Ms. -

The Paleoecology and Fire History from Crater Lake

THE PALEOECOLOGY AND FIRE HISTORY FROM CRATER LAKE, COLORADO: THE LAST 1000 YEARS By Charles T. Mogen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science and Policy Northern Arizona University August 2018 Approved: R. Scott Anderson, Ph.D., Chair Nicholas P. McKay, Ph.D. Darrell S. Kaufman, Ph.D. Abstract High-resolution pollen, plant macrofossil, charcoal and pyrogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) records were developed from a 154 cm long sediment core collected from Crater Lake (37.39°N, 106.70°W; 3328 m asl), San Juan Mountains, Colorado. Several studies have explored Holocene paleo-vegetation and fire histories from mixed conifer and subalpine bogs and lakes in the San Juan and southern Rocky Mountains utilizing both palynological and charcoal studies, but most have been at relatively low resolution. In addition to presenting the highest resolution palynological study over the last 1000 years from the southern Rocky Mountains, this thesis also presents the first high-resolution pyrogenic PAH and charcoal paired analysis aimed at understanding both long-term fire history and the unresolved relationship between how each of these proxies depict paleofire events. Pollen assemblages, pollen ratios, and paleofire activity, indicated by charcoal and pyrogenic PAH records, were used to infer past climatic conditions. Although the ecosystem surrounding Crater Lake has remained a largely spruce (Picea) dominated forest, the proxies developed in this thesis suggest there were two distinct climate intervals between ~1035 to ~1350 CE and ~1350 to ~1850 CE in the southern Rocky Mountains, associated with the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA) and Little Ice Age (LIA) respectively. -

Livlihood Strategy of Rana Tharu

LIVLIHOOD STRATEGY OF RANA THARU : A CASE STUDY OF GETA VDC OF KAILALI DISTRICT A Thesis Submitted to: Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of the Master Of Arts (MA) In Rural Development By VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No.: 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No.: 204/068 September 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District submitted to the Central Department of Rural Development, Tribhuvan University, is entirely my original work prepared under the guidance and supervision of my supervisor Prof Dr. Prem Sharma. I have made due acknowledgements to all ideas and information borrowed from different sources in the course of preparing this thesis. The results of this thesis have not been presented or submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree or for any other purposes. I assure that no part of the content of this thesis has been published in any form be ........................ VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No. : 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No : 204/068 Date: August 21, 2016 2073/05/05 . 2 RECOMMENDATION LETTER This is to certify that Mr. Vijaya Raj Joshi has completed this thesis work entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District under my guidance and supervision. I recommend this thesis for final approval and acceptance. _____________________ Prof. Dr. Prem Sharma (Supervisor) Date: Sep 14, 2016 2073/05/29 . -

Rakam Land Tenure in Nepal

13 SACRAMENT AS A CULTURAL TRAIT IN RAJVAMSHI COMMUNITY OF NEPAL Prof. Dr. Som Prasad Khatiwada Post Graduate Campus, Biratnagar [email protected] Abstract Rajvamshi is a local ethnic cultural group of eastern low land Nepal. Their traditional villages are scattered mainly in Morang and Jhapa districts. However, they reside in different provinces of West Bengal India also. They are said Rajvamshis as the children of royal family. Their ancestors used to rule in this region centering Kuchvihar of West Bengal in medieval period. They follow Hinduism. Therefore, their sacraments are related with Hindu social organization. They perform different kinds of sacraments. However, they practice more in three cycle of the life. They are naming, marriage and death ceremony. Naming sacrament is done at the sixth day of a child birth. In the same way marriage is another sacrament, which is done after the age of 14. Child marriage, widow marriage and remarriage are also accepted in the society. They perform death ceremony after the death of a person. This ceremony is also performed in the basis of Hindu system. Bengali Brahmin becomes the priests to perform death sacraments. Shradha and Tarpana is also done in the name of dead person in this community. Keywords: Maharaja, Thana, Chhati, Panju and Panbhat. Introduction Rajvamshi is a cultural group of people which reside in Jhapa and Morang districts of eastern Nepal. They were called Koch or Koche before being introduced by the name Rajvamshi. According to CBS data 2011, their total number is 115242 including 56411 males and 58831 females. However, the number of Rajvamshi Language speaking people is 122214, which is more than the total number this group. -

Ajit Kumar Baishya Email-ID

Faculty profile Name : Ajit Kumar Baishya Email-ID: [email protected] Tel.09435566247 Designation: Professor. Specialization: (a). Sociolinguistics with special reference to Pidgin and Creole Studies( b). Endangered and Minority Languages Present Research Interest: Lesser known languages of Assam, Lingua francas of the North- East India. Publications: Book (edited): Bilingualism and North East India, published by The Registrar, Assam University, Silchar, June 2008. Articles: 1. “The Making of Nagamese: A historical Perspective” Journal of Assam University, Silchar, January 2006. 2. “Language Maintenance by the Dimasas of Barak Valley: A Case Study” in Indian Linguistics, Vol. 67, 2006. 3. “Borrowing in Rabha: A Few Observations” in International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics, June 2006. 4. “Word Formation in Contemporary Assamese” in Journal of Assam University, Silchar, January 2007. 5. “Relexification in Nagamese: An Observation” in International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics, June 2007. 6. “Case Markers in Sylheti” in Indian Linguistics, Vol. 68, 2007. 7. “Reduplication in Modern Assamese” in Journal of Assam University, Silchar, January 2008. 8. “Word formation in Dimasa” in International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics, January 2008. 9. “Assamese: An SOV Language” in Indian Linguistics, Vol. 69, 2008. 10. “Sadri: The Lingua Franca” in The Humanities in the Present Context eds by Ramanan Mohan, P. Mohanty, T. Mukherjee, Allied Publishers, Hyderabad, 2009. 11. “Phonology of English Loan Words in Assamese” in Journal of Assam University, Silchar, January 2010. 12. “The Development of Script for Nagamese” in Manuscript and Manuscriptology in India eds by Nandi, S. G. and P. Palit, Kaveri Books, New Delhi, 2010. 13. “Problems of Teaching Assamese as a Second Language” in Literature, Culture and Language Education eds. -

Implementing the GF Resource Grammar for Nepali Language Master of Science Thesis in Software Engineering and Technology

müzik Implementing the GF Resource Grammar for Nepali Language Master of Science Thesis in Software Engineering and Technology DINESH SIMKHADA Chalmers University of Technology University of Gothenburg Department of Computer Science and Engineering Göteborg, Sweden, June 2012 The Author grants to Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg the non-exclusive right to publish the Work electronically and in a non-commercial purpose make it accessible on the Internet. The Author warrants that he/she is the author to the Work, and warrants that the Work does not contain text, pictures or other material that violates copyright law. The Author shall, when transferring the rights of the Work to a third party (for example a publisher or a company), acknowledge the third party about this agreement. If the Author has signed a copyright agreement with a third party regarding the Work, the Author warrants hereby that he/she has obtained any necessary permission from this third party to let Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg store the Work electronically and make it accessible on the Internet. Implementing GF Resource Grammar for Nepali language DINESH, SIMKHADA © DINESH SIMKHADA, June 2012. Examiner: AARNE RANTA, Prof. Chalmers University of Technology University of Gothenburg Department of Computer Science and Engineering SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Cover: concept showing translation of Nepali word संगीत (music) to different languages that are available in Grammatical Framework. Inspired from GF summer school poster and stock images Department of Computer Science and Engineering Göteborg, Sweden June 2012 Abstract The Resource Grammar Library is a very important part of Grammatical Framework. -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

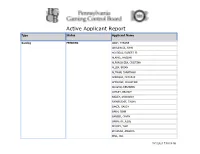

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name

Active Applicant Report Type Status Applicant Name Gaming PENDING ABAH, TYRONE ABULENCIA, JOHN AGUDELO, ROBERT JR ALAMRI, HASSAN ALFONSO-ZEA, CRISTINA ALLEN, BRIAN ALTMAN, JONATHAN AMBROSE, DEZARAE AMOROSE, CHRISTINE ARROYO, BENJAMIN ASHLEY, BRANDY BAILEY, SHANAKAY BAINBRIDGE, TASHA BAKER, GAUDY BANH, JOHN BARBER, GAVIN BARRETO, JESSE BECKEY, TORI BEHANNA, AMANDA BELL, JILL 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BENEDICT, FREDRIC BERNSTEIN, KENNETH BIELAK, BETHANY BIRON, WILLIAM BOHANNON, JOSEPH BOLLEN, JUSTIN BORDEWICZ, TIMOTHY BRADDOCK, ALEX BRADLEY, BRANDON BRATETICH, JASON BRATTON, TERENCE BRAUNING, RICK BREEN, MICHELLE BRIGNONI, KARLI BROOKS, KRISTIAN BROWN, LANCE BROZEK, MICHAEL BRUNN, STEVEN BUCHANAN, DARRELL BUCKLEY, FRANCIS BUCKNER, DARLENE BURNHAM, CHAD BUTLER, MALKAI 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING BYRD, AARON CABONILAS, ANGELINA CADE, ROBERT JR CAMPBELL, TAPAENGA CANO, LUIS CARABALLO, EMELISA CARDILLO, THOMAS CARLIN, LUKE CARRILLO OLIVA, GERBERTH CEDENO, ALBERTO CENTAURI, RANDALL CHAPMAN, ERIC CHARLES, PHILIP CHARLTON, MALIK CHOATE, JAMES CHURCH, CHRISTOPHER CLARKE, CLAUDIO CLOWNEY, RAMEAN COLLINS, ARMONI CONKLIN, BARRY CONKLIN, QIANG CONNELL, SHAUN COPELAND, DAVID 10/1/2021 7:00:09 AM Gaming PENDING COPSEY, RAYMOND CORREA, FAUSTINO JR COURSEY, MIAJA COX, ANTHONIE CROMWELL, GRETA CUAJUNO, GABRIEL CULLOM, JOANNA CUTHBERT, JENNIFER CYRIL, TWINKLE DALY, CADEJAH DASILVA, DENNIS DAUBERT, CANDACE DAVIES, JOEL JR DAVILA, KHADIJAH DAVIS, ROBERT DEES, I-QURAN DELPRETE, PAUL DENNIS, BRENDA DEPALMA, ANGELINA DERK, ERIC DEVER, BARBARA -

Department of English School of Languages and Literature Sikkim University Gangtok-737102

From Race to Nation: A Critical Perspective on the works of William Butler Yeats and Hari Bhakta Katuwal Vivek Mishra Department of English School of Languages and Literature Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Philosophy February 2017 Department of English School of Languages and Literature Sikkim University Gangtok-737102 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The researching and writing of this dissertation has proved to be a profitable experience for me in the academic field, and for this I owe a great debt to these people. Firstly, I take this opportunity to thank my supervisor Dr. Rosy Chamling for her guidance, support and encouragement that enabled me to complete my work. I thank Dr. Irshad Ghulam Ahmed, the Head of the Department for his guidance and insightful inputs. I am grateful to the faculty members of English Department for their support during my Masters in Philosophy programme. I thank my parents and my sister for their endless love and support. For help in finding material and providing insights vis-a-vis the Nepali poet in my study I want to thank many people, but particularly Smt. Kabita Chetry and Nabanita Chetry. My thanks extend to my friends – Bipin Baral, Afrida Aainun Murshida, Ghunato Neho, Anup Sharma and Kritika Nepal for their selfless assistance during my entire research work. Vivek Mishra CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Chapter – 1 INTRODUCTION (1 – 5) Chapter – 2 RACIAL AND NATIONALISTIC CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE WORKS OF YEATS AND KATUWAL (6 – 28) Chapter – 3 REPRESENTATION OF IRISH AND NEPALI CULTURES IN YEATS AND KATUWAL (29 – 43) Chapter – 4 LYRICAL QUALITY IN YEATS AND KATUWAL (44 – 53) Chapter – 5 CONCLUSION (54 – 66) CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The present study entitled “From Race to Nation: A Critical Perspective on the works of William Butler Yeats and Hari Bhakta Katuwal” shall be a comparative literary survey across languages i.e. -

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 35.2 — October 2012

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 35.2 — October 2012 REPORT ON THE 7TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE NORTH EAST INDIAN LINGUISTICS SOCIETY DON BOSCO INSTITUTE, GUWAHATI, INDIA 31 JANUARY–4 FEBRUARY, 2012 Lauren Gawne Amos Teo University of Melbourne Australian National University The 7th North East Indian Linguistics Society (NEILS7) workshop and conference was held from 31 January to 4 February 2012 at the Don Bosco Institute, Khaghuli Hills, in Guwahati, Assam. The event was organised by Jyotiprakash Tamuli and Anita Tamuli (Gauhati University), Mark Post (James Cook University) and Stephen Morey (La Trobe University). It was heartening to see many new as well as familiar faces, including local researchers from across India (particularly Assam and Manipur) and international ones from Australia, France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Of the countries neighbouring North East India, we also had researchers from Nepal, Bhutan, and, for the first time at a NEILS conference, researchers from Bangladesh. The two-day workshop that preceded the conference was run by Stephen Morey and Lauren Gawne and provided practical, hands-on training in basic language documentation for community members and students alike. This year we had the fortune to work with speakers of 12 different languages from North East India: Apatani, Bodo, Dimasa, Galo, Hakhun (Tangsa), Meithei, Meyor, Puroik, Rabha, Tai Phake, Tangam and Thadou Chin. It should be noted that some groups, especially those from Arunachal Pradesh, travelled up to four days to participate in the workshop. The first part of the workshop was spent familiarising ourselves with our recording equipment and some basic recording techniques, then we got straight into recording wordlists and stories. -

Adaptation and Identity of Yolmo People Contributiolls to Nepalese Studies, Vol

90 Occasional Papers Regmi, Mahesh C. 1976, Lalldowllership in Nepal, Berkeley: University of California Press. Rosser, Colin 1966, "Social Mobility in the Newar Caste System" in C. Von Ftirer-Haimendorf (ed.) Caste and Kill ill Nepal. Illdia and Cye/oll, Bombey: Asia Publishing House. Srinivas, M.N. 1966, Socia/ Challge ill Modern Illdia, Berkeley: ADAPTATION AND University of California Press IDENTITY OF YOLMO Sharma, Balchandra 1978 (2033 v.s.), Nepa/ko Airihasik Ruparekha (An Outline of the History of Nepal), Baranasi: Krishna Kumari Devi. Biood Pokharel Sharma, Prayag Raj 2004, "Introduction" in Andras HOfer, 2004, The Caste Hierarchy alld the State in Nepal: A Study ofthe Mu/ki Aill of1854, Kathmandu: Himal Books. An Overview Sharma, Prayag Raj 1978, "Nepal: Hindu-Tribal Interface" III This article focuses on adaptation and identity of Yolmo people ContributiOlls to Nepalese Studies, Vol. 16, No. I, pp. 1-4. living in the western part of the Sindhupalchok district. The Yolmo are traditionally herders and traders but later they diversified their economy and are now relying on tourism, wage labour and work aboard for income. It is believed that they arrived in the Melamchi area from Tibet from the 18'" century onwards. This article basically concerns on how Yolmo change their adaptive strategy for their survival and how did they become successful in keep their identity even though they have a small population. The economic adaptation in mountain region is very difficult due to marginal land and low productivity. Therefore they diversified their economy in multiple sectors to cope with the environment. Bishop states that "diversification involves exploiting one or more zones and managing several economic activities simultaneously" (1998:22).