Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Malibu 2 (Bareiss) (25) CVA 2

CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM UNITED STATES OF AMERICA • FASCICULE 25 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Fascicule 2 This page intentionally left blank UNION ACADÉMIQUE INTERNATIONALE CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM • MALIBU Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined closed shape, and lids from neck-amphorae ANDREW J. CLARK THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM FASCICULE 2 . [U.S.A. FASCICULE 25] 1990 \\\ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (Revised for fasc. 2) Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America.] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. (Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23) Fasc. 1- by Andrew J. Clark. At head of title: Union académique internationale. Includes index. Contents: fasc. 1. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes.—fasc. 2. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined open shape, and lids from neck-amphorae 1. Vases, Greek—Catalogs. 2. Bareiss, Molly—Art collections—Catalogs. 3. Bareiss, Walter—Art collections—Catalogs. 4. Vases—Private collections— California—Malibu—Catalogs. 5. Vases—California— Malibu—Catalogs. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. I. Clark, Andrew J., 1949- . IL J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Series: Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23, etc. NK4640.C6U5 fasc. 23, etc. 738.3'82'o938o74 s 88-12781 [NK4624.B37] [738.3'82093807479493] ISBN 0-89236-134-4 (fasc. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Athenian little-master cups Heesen, P. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heesen, P. (2009). Athenian little-master cups. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 8. NEANDROS, NEANDROS PAINTER, AMASIS PAINTER, OAKESHOTT PAINTER (nos. 209-34; pls. 60-66) 8.1 NEANDROS, NEANDROS PAINTER, c. 555/540, and NEANDROS, AMASIS PAINTER, c. 550/40 BC (nos. 209-15; figs. 79-82; pls. 60-61b) Introduction Epoiesen-signatures of Neandros mark at least five cups (209-11, 214-15, pls. 60-61a-b), and two partial examples (212-13) may also name him.759 Furthermore, Neandros possibly signed as painter in the egraphsen-signature on a pyxis lid from Brauron, although the writing is incomplete and the drawing style differs from that of the cups with his epoiesen-signatures.760 The signatures led J.D. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Athenian little-master cups Heesen, P. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heesen, P. (2009). Athenian little-master cups. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 2. XENOKLES, XENOKLES PAINTER, MULE PAINTER, PAINTER OF THE DEEPDENE CUP, POTTER AND PAINTER OF LONDON B 425 (nos. 50-92; pls. 13-27) Introduction Of the 41 cups and fragments with Xenokles’ epoiesen-signatures, 27 were known to J.D. Beazley, who assigned them to the potter Xenokles and recognized the hand of the so-called Xenokles Painter on most of them.254 Since then, another nine lip-cups and five band-cups can be added.255 Moreover, two unsigned lip-cups attributed to the Mule Painter can also be considered products of the potter Xenokles. -

GREEK VASES Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection

GREEK VASES Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California Cover: School boy with a lyre facing a "Walter Bareiss as a Collector," by © 1983 The J. Paul Getty Museum bearded man (his instructor?), tondo Dietrich von Bothmer (pp. 1-4) is 17985 Pacific Coast Highway of a Type B cup signed by the painter based, by permission, on The Malibu, California Douris; see No. 34, pp. 48-50. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, (For information about other Getty December 1969, pp. 425-428. Museum publications, please write the Photography by Penelope Potter, Bookstore, The J. Paul Getty Museum, except No. 30 and detail of No. 25 P.O. Box 2112, Santa Monica, supplied by The Metropolitan California 90406.) Museum of Art, New York. Design by Patrick Dooley. Typography by Typographic Service Company, Los Angeles. Printed by Jeffries Banknote Company, Los Angeles ISBN no. 0-89236-065-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS iv PREFACE v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 WALTER BAREISS AS A COLLECTOR 5 THE WORLD OF GREEK VASES 10 FORTY-SEVEN MASTERPIECES FROM THE BAREISS COLLECTION 67 CHECKLIST 88 GREEK VASE SHAPES PREFACE This museum is indeed fortunate to be able to present to the people of Southern California a selection of Greek vases from the remarkable collection of Molly and Walter Bareiss. All of us who enjoy the adventure of history, the search for beauty, and the evidence of scholarship will be grateful for the opportunity to see these 259 examples of some of the finest Attic black-figure and red-figure vases and fragments. Dietrich von Bothmer has described eloquently in his introduction the significance of the Bareiss Collection, which is undoubtedly the most important collection of its kind still privately owned. -

The Pottery from the North Slope of the Acropolis

THE POTTERY FROM THE NORTH SLOPE OF THE ACROPOLIS The pottery in question is the harvest of four seasons of excavation on the North Slope of the Acropolis.' Most of it is black-figured and red-figured ware. As the prehistoric pottery has already been described in solm-e detail by Mr. Broneer, nothing of earlier period than Geometric will be included here. At the end of the series the Hellenistic ware really closes the occupation of the site as far as anything of ceramic interest is concerned; the Roman is too scanty and too unimportant to merit inclusion.3 The custom of dropping r& zaXaua over the convenient edge of the Acropolis has been well established by centuries of precedent, to mention no other instances than the clearing of the citadel by the Athenians after the departure of the Persians4 and the further clearing of the hill by m-odern excavators.5 What wonder, then, that the newly- found pottery fragments are related to pieces discovered on the Acropolis during the last hundred years? Ten North Slope fragments join vases from the Acropolis and ' 1931-1934. Reports: Broneer, Hesperia, I, 1932, pp. 31ff.; IT, 1933, pp. 329 ff. First and foremost of all I must thank Dr. Broneer for the opporttunity of describing the fragments, for hiis generous and helpful attitude througlhout the couLrse of tlhis catalogtue, and for several usefuLl criticisms of the text; the authorities of the National Museum at Athens, and in especial Mrs. Semni KarouLsouiand Mr. Theophanides, for their hospitality and kindness during the process of matching the sherds with the fragments from the Acropolis, and for their permission to photograph certain hiitlherto unphotographed Acropolis pieces; the American Schlool of Classical Studies for providing the photographs for the article; Mr. -

Corpvsvasokvmi Antiqvorvm

VNION ACADEMIQVE INTERNATIONALE CORPVSVASOKVMI ANTIQVORVM RUSSIA POCCH5I THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM FOCY4APCTBEHHMH 3PMHTA)I( ST. PETERSBURG CAHKT-HETEPBYPF ATTIC BLACK-FIGURE DRINKING-CUPS, PART II by ANNA PETRAKOVA <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER - ROMA RUSSIA - FASCICULE xv THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM - FASCICULE VIII National Committee Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Russia Chairpersons Professor MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY, Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Arts Dr IRINA DANILOVA, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Committee Members Professor GEORGY VILINBAKHOV, Deputy Director of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg ANNA TROFIMOVA, Head of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Professor EDUARD FROLOV, Head of the Department of Ancient Greece and Rome, St. Petersburg State University IRINA ANTONOVA, Director, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow Member of the Russian Academy of Education Professor GEORGY KNABE, Institute of the Humanities, Russian State University of the Humanities, Moscow Dr OLGA TUGUSHEVA, Curator, Department of the Art and Archaeology of the Ancient World, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow ELENA ANANICH, Curator, Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. Russia. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER. - 32 cm. - In testa al front.: Union Academique Internationale. - Tit. parallelo in russo 15: The State Hermitage Museum, St. Peterbsurg. 8. Attic Black Figure Drinking Cups, Part 2. / by Anna Petrakova. - Roma: <<L'ERIVIA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, 2009. - 70 p., 67 p. di tav. : ill. 32 cm. ((Tavole segnate: Russia da 668 a 734. ISBN 978-88-8265556-3 CDD21. -

Attic Black Figure from Corinth: Ii

ATTIC BLACK FIGURE FROM CORINTH: II (PLATES 57-70) N THE SECOND HALF of the 6th century B.C., there is a substantial increase in the amount of Attic black-figuredpottery imported into Corinth.' That increaseis clearly il- lustratedby the fact that there are three times as many vases cataloguedhere as there were in "CorinthI", which was devotedto the material from the first half of the century.Some of the trends which were noted in "Corinth I" continue in the second half of the century. Drinking vessels predominate both before and after 550 B.C., for example, and Corinth importsa fairly wide range of shapes throughoutthe 6th century.There are, however, some importantdifferences between the pieces from the two periods. Only two kratersare dated to the first half of the century, while the krater is second only to the cup in popularity be- tween 550 and 500 B.C.The lekythos, which will be an important shape among Attic im- ports in the years after 500, is present in significantnumbers here. There were only three small lekythos fragments, perhaps all from the same vase, in "CorinthI"; eight are cata- logued here, all from the last quarterof the century.2 I This article is the second in a series of three devotedto the Attic black figure found at Corinth during the excavationsof the AmericanSchool of Classical Studies. For the first article in the series and for a description of the project,see "CorinthI". The following additions and correctionsshould be made to "CorinthI": The dinos fragments 3 are mentioned in D. A. -

Harmakhis Attic Cups from the J.L. Theodor Collection

ATTIC CUPS FROM THE J.L. THEODOR COLLECTION ATTIC CUPSFROM THE J.L. THEODOR COLLECTION THE J.L. CUPSFROM ATTIC HARMAKHIS HARMAKHIS 1 ATTIC CUPS FROM THE J.L. THEODOR COLLECTION HARMAKHIS Rue des Minimes 3 (Sablon) - 1000 Brussels - Belgium Mobile: +32 (0)475 650 285 [email protected] - www.harmakhis.be 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 Foreword 6 Lip-cup signed Taleides 10 Lip-cup probably by the Phrynos Painter 14 Lip-cup signed Sokles 18 Band-cup signed Xenokles 20 Lip-cup attributed to the Centaur Painter 24 Band-cup signed Hermogenes 28 Band-cup attributed to Elbows Out 32 Band-cup attributed to the Centaur Painter 36 Window Band-cup 38 Top-Band Stemless Cup 42 Eye-cup attributed to the Nikosthenic Workshop I would like to express my sincere thanks to Prof. Dr. Herman Brijder FOREWORD who wrote most descriptions in this catalogue and also to my colleague Jean-David Cahn for his description of the Nikosthenic Workshop eye-cup Jacques Theodor is one of the most fascinating personalities whom I have met during my career as a dealer in published in the TEFAF 2013 catalogue, which I shortened. ancient art and it is a real privilege for me to be given the opportunity to offer for sale his collection of Attic cups. Jacques Billen It is almost impossible to summarise here his unconventional and multi-faceted lifetime. Jacques Theodor was born in Brussels 1926. After a short career in textile industry, Theodor’s life took a totally different turn as a pioneer of scuba diving, underwater photography and as a speleologist in the late 1940’s. -

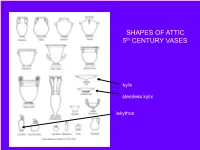

SHAPES of ATTIC 5Th CENTURY VASES

SHAPES OF ATTIC 5th CENTURY VASES kylix stemless kylix lekythos Attic Lekythos From Black Figure to Red Figure 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Deianeiran Lekythos (round) Early 6th Century 2 Deianeiran Lekythos (oval) Early 6th Century 3 Early Shoulder Lekythos c. 560 BCE 4 Shoulder Lekythos c. 540—530 BCE 5 Standard lekythos c. 500 BCE 6. Chimney Lekythos c. 470 BCE (red figure) Deianeiran Lekythos (round) Gorgon Painter Attic early These drawings from: Folsom’s 6th century BCE (left) Attic Black-Figured Pottery Neck Ring 1 2 3 4 Corinthian Lekythos Attic Deianeiran Attic Deianeiran Early Shoulder Lekythos Lekythos, near the Lekythos, Amasis Amasis Painter c. 550- Gorgon Painter Painter, 550-530 BCE 530 BCE 5.Standard lekythos c. 500 BCE 6. Chimney Lekythos c. 470 BCE (red figure) 4 5 6 White Ground Lekythos Edinburg Painter c. 500 BCE Standard Lekythos Chimney Lekythos Daybreak Painter Palermo c. 500 BCE (center) 510-500 BCE The boatman, Charon. ferries the souls Red Figure Chimney White Groung Chimney across the River, Styx Lekythos 5th century Lekythos 5th century X-ray lekythoi were offered at tombs Black Figure Stemmed Cup Shapes 600-500 BCE First Quarter (600-575) Comast Cups Second Quarter (575-550) Siana Cups Third Quarter (550-525) Lip Cups and Band Cups Forth Quarter (530-500) Proto A Cups Attic Comast Cup ca 580-570 BCE (above right) Corinthian Comast Cup Attic Skyphos with Komasts 600-575 BCE (above left) 590-570 BCE (below right) Attic Comast Cup ca 590-570 BCE (below left) Skyphos with Komasts c. -

Athenian Little-Master Cups

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Athenian little-master cups Heesen, P. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heesen, P. (2009). Athenian little-master cups. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 INTRODUCTION1 This study deals with Athenian little-master cups, a type of drinking cup which was made over a fairly long period by a large number of potters and painters in sixth century BC Athens. Whereas their production extended between c. 560 and 480 BC, they were primarily made between c. 550 and 510 BC. The present author has information about more than 5,100 cups and fragments of this type of cups. Since they are too numerous to be considered in their entirety in this study, a selection had to be made. -

Corinthian, Attic Black Figure and Red Figure Pottery from Sinope1

Anadolu / Anatolia 46, 2020 K. Görkay CORINTHIAN, ATTIC BLACK FIGURE AND RED FIGURE POTTERY FROM SINOPE1 Kutalmış GÖRKAY* In memory of Ekrem Akurgal and Cevdet Bayburtluoğlu Keywords: Black Sea • Sinope • Greek colonization • Corinthian Pottery • Attic Black Figure pottery • Attic Red Figure pottery. Abstract: The article deals with Corinthian; Attic Black and Red Figure pottery finds from the excavations conducted by E. Akurgal and L. Budde in the ancient city of Sinope between 1951 and 1953. The study also assesses relevant pottery finds which were found in successive periods found in Sinope and their evaluations in statistical analysis. Assessment of the pottery finds has indicated that the earliest Corinthian products in Sinope are represented by an oinochoe from LPC period. Having relatively parallel pottery densities with the other cities on the Black Sea area, the amount of Attic red-figured ceramics in Sinope appear to increase after the arrival of the Athenian citizens, who settled in Sinope, after the new colonization policies promoted during the reign of Pericles in the last quarter of the 5th century BCE. * Prof. Dr. Kutalmış GÖRKAY, Ankara Üniversitesi, Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi, Klasik Arkeoloji Anabilim Dalı, Gönüllü Araştırma Profesörü, Sıhhiye/ANKARA, e-posta: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-2680-0439 Gönderilme tarihi: 02.06.2020; Kabul edilme tarihi: 10.08.2020 DOI: 10.36891/anatolia.747265 1 The permission to work on this material had been kindly given to me by the late Professor Ekrem Akurgal and Professor Cevdet Bayburtluoğlu to whom this article is dedicated. The paper presented here was made possible thanks to the scholarship provided by Ausonius Institute of Archaeology (Maison de l’Archéologie, Université Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3 and CNRS (2002) and opportunities given by Harvard University, Department of the Classics (2003). -

Attic Black Figure from Corinth: I

ATTIC BLACK FIGURE FROM CORINTH: I (PLATES 12-16) TNHROUGHOUT almost its entire history, Attic black figure was imported into Corinth. The earliest black-figuredvase dates to the beginning of the 6th centuryB.C., while the latest examples, with the exception of Panathenaicamphorae, belong to the mid- 5th century.A broadspectrum of shapes, painters,and subjectsappears at Corinth,and it is the purpose of this article and its successorsto presentthe Attic black figure found at the site and to discuss its broaderimplications, both artistic and commercial.1 The earliest black-figuredvase found at Corinth is the olpe C-32-235. Assigned by Beazley to the group of the Early Olpai, it is certainly early in that sequence, as its shape 1 This is the first of a series of three articlesdevoted to the Attic black figure found at Corinthin the excava- tions of the American School of Classical Studies. I have divided the material chronologically;this article catalogues works from before ca. 550 B.C., while the subsequent studies will cover the second half of the 6th century and the first half of the 5th century, respectively.These divisions are somewhat arbitrary,and I have not adhered to them absolutely, as in those cases where it seemed more importantto keep a group of pieces together. For example, all Siana cups, even those which date to the 540's, are included here, and all Little Master cups will appear in the secondarticle. Some materialwill be studiedelsewhere by other scholars:E. G. Pembertonwill publish the Attic black figure from the Sanctuaryof Demeter and Kore on Acrocorinthin Corinth XVIII, i, forthcoming;J.