The Craft Distillery Movement Keeps Growing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COX's CREEK SHEPHERDSVILLE DANVILLE Elizabethtown Frankfort Lebanon Somerset Glasgow Owensboro the B-LINE

THE B-LINE 4 11 1 frankfort 3 7 10 13 16 SHEPHERDSVILLE 14 15 7 5 5 COX’S CREEK 8 Owensboro 2 12 6 Elizabethtown 9 DANVILLE Lebanon Miles Between Distilleries Angel’s EnvyBardstown BourbonBulleit Frontier CompanyEvan Whiskey WilliamsFour Experience Roses DistilleryHeaven HillJim Distilleries Beam DistilleryLux Row Maker’s MarkMichter’s Distillery FortOld Nelson Forester DistilleryO.Z. Tyler Rabbit Hole TownDistillery BranchWild Distillery Turkey WoodfordDistillery Reserve Distillery Angel’s Envy — 46 5 1 60 44 28 44 61 1 1 111 1 76 57 60 Bardstown Bourbon Company 46 — 48 47 47 5 20 3 31 47 45 127 46 59 43 56 Bulleit Frontier Whiskey 5 48 — 5 64 45 29 46 62 6 11 111 13 81 61 65 61 Evan Williams Experience 1 47 5 — 60 44 28 45 61 1 1 109 2 76 57 60 Four Roses Distillery 60 47 64 60 — 38 53 37 54 59 59 160 57 24 8 21 Heaven Hill Distilleries 44 5 45 44 38 — 18 4 18 44 42 124 43 60 45 56 Jim Beam Distillery 28 20 29 28 53 18 — 18 35 28 27 121 28 74 60 71 Lux Row 44 3 46 45 37 4 18 — 15 43 43 127 43 58 43 55 Maker’s Mark Distillery 61 31 62 61 54 18 35 15 — 59 58 134 58 75 61 72 Michter’s Fort Nelson Distillery 1 47 6 1 59 44 28 43 59 — 1 108 2 78 56 60 Old Forester 1 45 11 1 59 42 27 43 58 1 — 109 1 76 56 60 O.Z. -

Brand Listing for the State of Texas

BRAND LISTING FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS © 2016 Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits SOUTHERNGLAZERS.COM Bourbon/Whiskey A.H. Hirsch Carpenders Hibiki Michter’s South House Alberta Rye Moonshine Hirsch Nikka Stillhouse American Born Champion Imperial Blend Old Crow Sunnybrook Moonshine Corner Creek Ironroot Republic Old Fitzgerald Sweet Carolina Angel’s Envy Dant Bourbon Moonshine Old Grand Dad Ten High Bakers Bourbon Defiant Jacob’s Ghost Old Grand Dad Bond Tom Moore Balcones Devil’s Cut by Jim James Henderson Old Parr TW Samuels Basil Haydens Beam James Oliver Old Potrero TX Whiskey Bellows Bourbon Dickel Jefferson’s Old Taylor Very Old Barton Bellows Club E.H. Taylor Jim Beam Olde Bourbon West Cork Bernheim Elijah Craig JR Ewing Ole Smoky Moonshine Westland American Blood Oath Bourbon Evan Williams JTS Brown Parker’s Heritage Westward Straight Blue Lacy Everclear Kavalan Paul Jones WhistlePig Bone Bourbon Ezra Brooks Kentucky Beau Phillips Hot Stuff Whyte & Mackay Bonnie Rose Fighting Cock Kentucky Choice Pikesville Witherspoons Bookers Fitch’s Goat Kentucky Deluxe Private Cellar Woodstock Booze Box Four Roses Kentucky Tavern Rebel Reserve Woody Creek Rye Bourbon Deluxe Georgia Moon Kessler Rebel Yell Yamazaki Bowman Hakushu Knob Creek Red River Bourbon Bulleit Bourbon Hatfield & McCoy Larceny Red Stag by Jim Beam Burnside Bourbon Heaven Hill Bourbon Lock Stock & Barrel Redemption Rye Cabin Fever Henderson Maker’s Mark Ridgemont 1792 Cabin Still Henry McKenna Mattingly & Moore Royal Bourbon Calvert Extra Herman Marshall Mellow Seagram’s 7 -

WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished

WHISK(E)YS BOURBON WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished ............................................................ $12.00 High West Campfire Whiskey ................................................................... $10.00 Basil Hayden's ............................................................................................ $12.00 Jack Daniel's ............................................................................................... $8.00 Belle Meade Sour Mash Whiskey ............................................................. $10.00 Gentleman Jack ........................................................................................ $11.00 Belle Meade Madeira Cask Bourbon ........................................................ $15.00 George Dickel No.12 ................................................................................... $9.00 Blackened Whiskey .................................................................................... $10.00 Mitcher's American Whiskey .................................................................... $12.00 Buffalo Trace ............................................................................................... $8.00 Mitcher's Sour Mash Whiskey .................................................................. $12.00 Bulleit Bourbon ............................................................................................ $8.00 CANADIAN WHISKY Bulleit Bourbon 10 year old ...................................................................... $13.00 -

The 25 Most Important Bourbons Ever Made

The 25 Most Important Bourbons Ever Mad If you asked a spirits expert a quarter century ago to name the most important bourbons ever made, they might have wondered whether America’s home-grown whiskey deserved such analytical consideration. Bourbon was in the doldrums, unappreciated and underdrunk. But today, thanks to a boom that shifted into high gear around the turn of the century, bourbon is arguably the most talked-about, most obsessed-over and most in-demand spirit in the world. To better assess how we got here, we consulted with 23 bourbon experts, including distillers, journalists, authors, whiskey-bar owners and one whiskey-centric-liquor-store proprietor. Each participant named five to ten bourbons that made a difference—not their favorite bourbons, or the ones they thought tasted best, but those bottles that were influential, innovative or otherwise held a significant place in bourbon history. They were allowed to reach way back to pre-Prohibition years, cite bourbons they could never have tasted, and yes, in the case of distillers, include their own creations. (One self-serving endorsement would not land them a spot on this list, however, as every bourbon here received multiple votes.) The final order was determined strictly by the votes received. There were a number of ties in the lower rankings. In those cases, editorial judgment determined final rankings. In a few instances, the panelists indicated complete lines of bourbons that bore the same name, not just a single bottling. In other cases, panelists pointed out different bottlings within a single line. As the arguments behind these choices were often similar, these votes were sometimes combined and placed within the rankings as a bourbon label’s complete line. -

Cave Hill Heritage Foundation to Offer First Interactive Bourbon Distillers Tour in the History of Cave Hill Cemetery

Media Release For Immediate Announcement January 21, 2014 Contact: J. Michael Higgs, Coordinator, Cave Hill Heritage Foundation, Inc. Public Relations, Cave Hill Cemetery Co., Inc. 502-813-7761 Office Direct 502-639-9393 Cellular Topic: Cave Hill Heritage Foundation Announces Bourbon History Tour Cave Hill Heritage Foundation to Offer First Interactive Bourbon Distillers Tour in the History of Cave Hill Cemetery The Cave Hill Heritage Foundation is proud to announce the creation of a new tour for the 2014 tour season called, “A Journey through Bourbon History at Cave Hill Cemetery” with Michael Veach. Dates for the tours are: Sunday, May 18, 2014 and Sunday, September 14, 2014. The tours will begin at 1:00 p.m. Admission is $35 per person, with all proceeds benefiting the Cave Hill Heritage Foundation. This will be the first interactive tour ever offered at Cave Hill Cemetery. Participants can utilize our app, called “Cemetery Tours” in the IPhone App Store and the Google Play Store for smartphone users. The app is free and is also available through the cemetery website, www.cavehillcemetery.com. Using the app, participants can follow along a GPS marked map of Cave Hill Cemetery and find photographs of the individuals highlighted and assorted videos of the distiller or their associated distillery as they are standing at the gravesite. Stops on the tour will include the following: Julian Proctor Van Winkle, “Pappy Van Winkle” Owsley Brown- Brown-Forman Distillery Frederick Stitzel- Patented the warehouse ricking system Alexander Farnsley- Partner with Stitzel-Weller Distillery Thomas Jeremiah Beam- Jim Beam Distillery George Forman- Partner of George Garvin Brown (namesake of Brown-Forman) Paul Jones- Kentucky’s First Distiller- Four Roses Distillery John Charles Weller- Stitzel-Weller Distillery Phillip Hollenbach- Glencoe Distillery J.T.S. -

Vermont 802Spirits Current Complete Price List September 2021 1 of 24

Vermont 802Spirits Current Complete Price List September 2021 VT REG NH VT Sale Price Code Brand Size Price Price Price Save Proof Status per OZ Brandy Brandy Domestic 056308 Allen's Coffee Brandy 1.75L 19.99 15.99 17.99 2.00 70 High Volume 0.30 056306 Allen's Coffee Brandy 750ML 9.99 7.99 60 High Volume 0.39 056310 Allen's Cold Brew Coffee Brandy 750ML 14.99 60 New 0.59 052374 Coronet VSQ Brandy 375ML 4.99 80 High Volume 0.39 052584 E & J Superior Res. VSOP 1.75L 25.99 23.99 80 High Volume 0.44 052581 E & J Superior Res. VSOP 375ML 5.99 5.49 80 High Volume 0.47 052582 E & J Superior Res. VSOP 750ML 14.99 12.99 12.99 2.00 80 High Volume 0.51 052598 E & J VS Brandy 1.75L 24.99 21.99 22.99 2.00 80 High Volume 0.39 052596 E & J VS Brandy 750ML 12.99 11.99 80 High Volume 0.51 052563 E & J XO Brandy 750ML 16.99 15.99 80 High Volume 0.67 073864 E&J Spiced Brandy 750ML 9.99 60 New 0.39 053536 Laird's Applejack 750ML 17.99 15.99 80 High Volume 0.71 054916 Leroux Jezynowka Blackberry Brandy 750ML 11.99 8.99 70 Medium Volume 0.47 900488 Mad Apple Brandy 750ML 46.99 84 Medium Volume 1.85 054438 Mr. Boston Apricot Brandy 1.75L 17.99 13.99 70 High Volume 0.30 054436 Mr. -

2017 Results 2018 Results

20172018 RESULTSRESULTS 100% Agave Tequila Silver/Blanco Genever Aquavit 100% Agave Tequila Reposado Flavored/Infused Gin Straight Bourbon Whiskey Aquavit 100% Agave Mezcal Cocktail Syrup & Cordial 100% Agave Tequila Anejo Absinthe (blanche/verte) Other Whiskey Gin Flavor/Infused Tequila Individual Bottle Design 100% Agave Tequila Extra Anejo Liqueur Flavored/Infused Whiskey Flavor/Infused Gin Rum Series Bottle Design 100% Agave Mezcal Silver/Blanco Pre-Mixed Cocktail (RTD) Individual Bottle Design Soju/Shochu/Baijiu Flavor/Infused Rum Flavored/Infused Tequila/Mezcal Other Miscellaneous Spirit Series Bottle Design BitterVodka MixerCognac Aperitivo/AperitifFlavor/Infused Vodka Syrup/CordialGrappa AmaroStraight Bourbon Whiskey GarnishEau-de-Vie/Fruit Brandy (non-calvados) VermouthFlavor/Infused Whiskey RumOther Brandy ArmagnacOther Whiskey Flavored/InfusedApertifs/Bitters Rum Cognac100% Agave Tequila Silver/Blanco Soju/ShochuLiqueur Brandy Vodka 100% Agave Tequila Reposado Pre-Mixed Cocktails (RTD) Consumers’ Choice Consumers’ Choice Other Brandy Flavored/Infused Vodka Awards 100% Agave Tequila Anejo Mixer` Awards Gin Other Vodka BACK TO CATEGORIES SIP AWARDS | 2018 SPIRIT RESULTS 100% AGAVE TEQUILA SILVER/ DOUBLE GOLD SILVER BLANCO Luxco Inc Suerte Tequila El Mayor Tequila Blanco Suerte Tequila Blanco BEST OF CLASS - PLATINUM www.luxco.com www.drinksuerte.com United States | 40.0% | $24.99 @suertetequila Destilería Casa de Piedra Mexico | 40.0% | $29.99 Tequila Terraneo Organico Juan More Time Tequila www.cobalto.destileriacasadepiedra.com Juan More Time Tequila Blanco - Artesanal & Heaven Hill Brands @organictequilas Organic Lunazul Tequila Blanco Mexico | 40.0% | $64.99 www.juanmoretimetequila.com www.heavenhill.com @juanmoretime_tequila United States | 40.0% | $19.99 Mexico | 40.0% | $49.00 PLATINUM Silver/Blanco Tequila 100% Agave Suave Spirits INternational LLC Lovely Rita Spirits Inc. -

What's New in Kentucky Bourbon

WHAT’S NEW IN KENTUCKY BOURBON Bourbon Events, Distillers, Expansions Enhance Guests’ Experiences 2021 Bourbon Trail™ Passport and Field Guide released – The Kentucky Distillers’ Association recently released the 2021 Bourbon Trail™ Passport and Field Guide, a 150-page document containing all the information needed for planning travel, food, tours, tastings and cocktails, plus tips and tricks about the 37 distilleries that are part of the official Kentucky Bourbon Trail® and Kentucky Bourbon Craft Trail®. The guide will be sold at all distilleries included on the trails, the KBT Welcome Center® and online. New this year, in addition to collecting stamps for visiting and touring spots, the passport will also unlock perks such as private barrel selections, tastings, special barware and access to collectible bottles. https://www.msn.com/en-us/foodanddrink/cocktails/new-bourbon-passport-is-your-perfect-guide-to-the-best-whiskey-in- kentucky/ar-AAKRFQf & https://kybourbontrail.com/field-guide/ African American owned distillery planned for Lexington – African American Lexington entrepreneurs Sean and Tia Edwards plan to build a distillery, music hall, and event center in downtown Lexington. Fresh Bourbon Distilling Co.’s 34,000-square-foot facility will be near the Distillery District, with a likely completion date in late 2021. https://smileypete.com/business/fresh-bourbon-distilling/ B-Line in northern Kentucky adds new stops – On National Bourbon Day, June 14, 2021, the B-Line announced four additions to Northern Kentucky’s bourbon experience. The new stops include Smoke Justis and Libby’s Southern Comfort in Covington, Three Spirits Tavern in Bellevue and The Beehive Augusta Tavern in Augusta. -

Whiskey Menu

PREMIUM WHISKEY SELECTION An Púcán is a founder member of The Galway Whiskey Trail which was established in 2015 to celebrate the 200th Anniversary of the opening of The Nun’s Island Distillery in Galway. An Púcán is also the proud winner of Best Single Cask Irish Whiskey for our collaboration with Teeling Whiskey Company at 2015 Irish Whiskey Awards as well as Gold Medal for Connacht Whiskey Bar of the year. An Púcán where the sharing of whiskey is not only for the angels…. An Púcán is famed for its vibrancy and passion and we pride ourselves at being able to offer our customers access to a tailor made whiskey experience that will not only engage the connoisseur but also the curious…. It’s from this passion that the An Púcán Whiskey society was created, bringing together like minded people to appreciate and enjoy some of the best whiskeys around. Regular events with the top names in the industry help our members fuel their passion for remarkable drinks. “The light music of whiskey falling into a glass - an agreeable interlude.” James Joyce IRISH WHISKEY MIDLETON DISTILLERY Originally formed in the 60s by Powers, Jameson & Cork Distilleries – this distillery produces some of the finest Single Pot Still whiskey on the island. The No.1 Irish whiskey in the world, Jameson is triple distilled, boasting a perfectly balanced, well-rounded flavour. Whiskey Style Cask(s) ABV € Jameson Triple Blend Bourbon/Sherry 40% 5.60 Irish Whiskey Jameson Triple Blend Bourbon/Oloroso 40% 5.60 Crested Jameson Bourbon/ Triple Blend 40% 17.10 Gold Reserve Oloroso/Virgin -

Ann Arbor Whiskies

Ashley’s Whiskey Collection Featuring a variety of 60+ Single Malts, Blends, Bourbons, Irish Whiskeys, and Cognacs Western Islands (Islay, Jura & Skye) Laphroig 10 Year Nose is thick peat with a soft, oaky Ardbeg (10) background. Continuous gentle waves of dry peat Astoundingly smoky nose with a full, robust lap upon the tastebuds but are balanced by a palate of peat smoke flavoured with turf and sweet malt middle and vanilla. Finishes long and lapsang souchong tea.Finishes salty, long and peaty, the shy vanilla now begins to show as the filled with fragrant peat reek. A punch in the oak adds a certain dryness. 9.50 chops from a stroppy Islay middleweight. An instant warming tang of smoke that Flavour-packed yet delicate. 9.50 18 Year fades into smooth floral scents and blends seam- Bowmore lessly into an oaky nuttiness, leaving a lasting 12 Year Fragrant smokiness against an oily, sweetness.Finishes full bodied, long with a earthy, background. Some seaweed. Some sherry. luxurious oily smoothness. 16.00 Smokiness is sustained all the way through and surges in the finish with lots of salt. 8.75 Talisker (10) Peat-smoke nose with sea-water saltiness and cit- 18 Year A smoothly aromatic, nutty malt rus sweetness. Full-bodied palate with a dried-fruit with an appetizing medicinal Islay character. sweetness and strong barley-malt flavours. Long, Palate is rounded, firm, malty, dry creaminess. peppery finish with sweetness. 13.00 Tightly combined flavours with a malty, smoky finish.16.00 Bruichladdich (Signatory 19yr.) Distilled 1992, Bottled 2012; Hogshead Aged Lagavulin (16) Distilled before the distillery was mothballed in Deep amber gold in appearance, with an 1995, sold and restarted in 2001. -

August 2021 SPA Product List

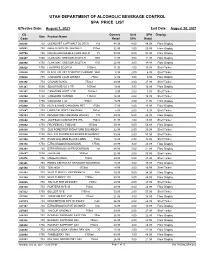

UTAH DEPARTMENT OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE CONTROL SPA PRICE LIST Effective Date: August 1, 2021 End Date: August 28, 2021 CS Current Unit SPA Display Size Product Name Code Retail SPA Retail 005036 750 GLENLIVET 12YR MALT SCOTCH 750ml 48.99 4.00 44.99 Floor Display 005662 750 NAKED GROUSE WHISKEY 750ml 32.99 3.00 29.99 Floor Display 005700 750 MACALLAN DOUBLE CASK GOLD 750ml 59.99 5.00 54.99 Floor Display 006997 1000 CLAN MAC GREGOR SCOTCH 1000ml 14.99 3.00 11.99 Floor Display 006998 1750 CLAN MAC GREGOR SCOTCH 1750ml 22.99 3.00 19.99 Floor Display 008828 1750 LAUDERS SCOTCH 1750ml 21.99 2.00 19.99 Shelf Talker 010550 750 BLACK VELVET TOASTED CARAMEL WHSK 750ml 8.99 2.00 6.99 Shelf Talker 010626 750 CANADIAN CLUB WHISKY 750ml 12.99 3.00 9.99 Floor Display 011296 750 CROWN ROYAL 750ml 29.99 2.00 27.99 Shelf Talker 011347 1000 SEAGRAMS VO 6 YR 1000ml 19.99 3.00 16.99 Floor Display 012287 1000 CANADIAN HOST 3 YR 1000ml 9.95 2.00 7.95 Shelf Talker 012308 1750 CANADIAN HUNTER 1750ml 16.99 2.00 14.99 Shelf Talker 012408 1750 CANADIAN LTD 1750ml 15.95 4.00 11.95 Floor Display 012888 1750 RICH & RARE CANADIAN PET 1750ml 17.99 4.00 13.99 Floor Display 013647 750 LORD CALVERT CANADIAN 750ml 8.99 2.00 6.99 Shelf Talker 014199 1750 PENDLETON CANADIAN WHISKY 1750ml 49.99 5.00 44.99 Floor Display 015648 750 JAMESON CASKMATES IPA 750ml 31.99 2.00 29.99 Shelf Talker 015832 1750 PROPER NO. -

Cocktails and Spirits List 1 / 2019 English

ENGLISH COCKTAILS AND SPIRITS LIST 1 / 2019 LUXURY IN A DRINK Flavours which introduce and delight. Re-visitations and new creations, the fruit of the expertise of Raise the Bar. Classic compositions and the most innovative of cocktails all become part of the Langosteria experience. Characterised by creations which, step by step, are made to accompany you from the moment you walk through the door to the final goodbye. From an “Americano a modo mio” to an exotic “Passion dreams”. From “Shibuya” to “Manhattan”, via “Milano New York”, the byword is “Uno mas”. Our “Giuda” will never let you down. But there is no doubt that “Irma” will seduce you. And those who prefer to thoroughly honour tradition can take their pick from “Martini Cocktail”, “Old Fashioned” and “Margarita”. A wide range of recipes. For a selection which may be different every time but is always yours. A new ritual, because forgetting the hectic life is a luxury, one which starts right now. “I’m a man of simple tastes, I’m always satisfied with the best”. The words of Oscar Wilde, the interpretations of the after-dinner drink in Langosteria style. Oceanic journeys in search of unique reserves. A route which leads to vintage Bas Armagnac and rums from exotic lands. For those who prefer contemplation, there are the various evolutions of whisky, from those which aim for the utmost in perfection to the Samaroli Blends, with their often-unique characteristics. A unique experience, evening after evening. To enthral and amaze. But always characterised by the international style of Langosteria.