I:\28531 Ind Law Rev 46-2\46Masthead.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

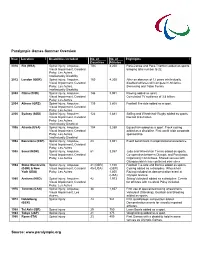

Paralympic Games Summer Overview Source

Paralympic Games Summer Overview Year Location Disabilities included No. of No. of Highlights Countries Athletes 2016 Rio (BRA) Spinal injury, Amputee, TBC 4,200 Para-Canoe and Para-Triathlon added as sports Visual Impairment, Cerebral bringing total number to 22. Palsy, Les Autres, Intellectually Disability 2012 London (GBR) Spinal injury, Amputee, 160 4,200 After an absence of 12 years intellectually Visual Impairment, Cerebral disabled athletes will compete in Athletics, Palsy, Les Autres, Swimming and Table Tennis. Intellectually Disability 2008 China (CHN) Spinal injury, Amputee, 146 3,951 Rowing added as sport. Visual Impairment, Cerebral Cumulated TV audience of 3.8 billion. Palsy, Les Autres 2004 Athens (GRE) Spinal injury, Amputee, 135 3,808 Football 5-a-side added as a sport. Visual Impairment, Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres 2000 Sydney (AUS) Spinal injury, Amputee, 122 3,881 Sailing and Wheelchair Rugby added as sports. Visual Impairment, Cerebral Record ticket sales. Palsy, Les Autres, Intellectually Disabled 1996 Atlanta (USA) Spinal injury, Amputee, 104 3,259 Equestrian added as a sport. Track cycling Visual Impairment, Cerebral added as a discipline. First world wide corporate Palsy, Les Autres, sponsorship. Intellectually Disabled 1992 Barcelona (ESP) Spinal injury, Amputee, 83 3,001 Event benchmark in organizational excellence. Visual Impairment, Cerebral Palsy, Les Autres 1988 Seoul (KOR) Spinal injury, Amputee, 61 3,057 Judo and Wheelchair Tennis added as sports. Visual Impairment, Cerebral Co-operation between Olympic and Paralympic Palsy, Les Autres Organizing Committees. Shared venues with Olympics which has continued ever since 1984 Stoke Mandeville Spinal injury, Amputee, 41 (GBR) 1,100 Football 7-a-side and Boccia added as sports. -

Mitochondrial Ubiquitin Ligase MITOL Blocks S-Nitrosylated MAP1B-Light Chain 1-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neuronal Cell Death

Mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase MITOL blocks S-nitrosylated MAP1B-light chain 1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal cell death Ryo Yonashiro, Yuya Kimijima, Takuya Shimura, Kohei Kawaguchi, Toshifumi Fukuda, Ryoko Inatome, and Shigeru Yanagi1 Laboratory of Molecular Biochemistry, School of Life Sciences, Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, Hachioji, Tokyo 192-0392, Japan Edited by Ted M. Dawson, Institute for Cell Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and accepted by the Editorial Board January 3, 2012 (received for review September 14, 2011) Nitric oxide (NO) is implicated in neuronal cell survival. However, recently been shown to be S-nitrosylated on cysteine 257 and excessive NO production mediates neuronal cell death, in part via translocated to microtubules via a conformational change of LC1 mitochondrial dysfunction. Here, we report that the mitochondrial (12). Additionally, LC1 has been implicated in human neuro- ubiquitin ligase, MITOL, protects neuronal cells from mitochondrial logical disorders, such as giant axonal neuropathy (GAN), frag- damage caused by accumulation of S-nitrosylated microtubule- ile-X syndrome, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, and Parkinson associated protein 1B-light chain 1 (LC1). S-nitrosylation of LC1 in- disease (10, 13, 14). Therefore, the control of S-nitrosylated LC1 duces a conformational change that serves both to activate LC1 and levels is critical for neuronal cell survival. fi to promote its ubiquination by MITOL, indicating that microtubule We previously identi ed a mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase, MITOL (also known as March5), which is involved in mito- stabilization by LC1 is regulated through its interaction with MITOL. – Excessive NO production can inhibit MITOL, and MITOL inhibition chondrial dynamics and mitochondrial quality control (15 19). -

ATTACHMENT 5 Lrgo-C960965-00-V

ATTACHMENT5 4. SHOCIqVIBRATION, AND ACOUSTICSANALYSIS 5. DESIGN GOALS/REQUIREMENTS vtHg-2-0!'5 REV. O SPECIfICATIONS TITLE DOCUMENTNO. REV. EquipmentSpecif cations Main RoughingPurnp Carts v049-2-001 Main TurbomolecularPump Cans v049-2-002 4 Auxiliary TurbomolecularPump Cans v049-2-003 Ion Pumps v049-2-004 2 ll2 and 122cm GateValves v049-2-005 J 10" and 14" GateValves v049-2-006 I VacuumGauges v049-2-007 0 BakeoutBlanlet System v049-2-009 I PortableSoft Wall CleanRooms vM9-2-010 0 CleanAir Supplies v049-2-011 I LN: Dewars v049-2-013 1 VacuumJack*ed Piping v049-2-016 PI BellowsExpansion Joints v049-2-017 I AmbientAir Vaporizers v049-2-055 0 80K PumpRegaroation Heater v049-2-056 0 SmallVacuum Valves v&9-2-059 0 CleanQh Tum Valves v049-2-050 0 CryogenicControl Valves v049-2-062 0 BakeoutCart v049-2-068 2 LrGO-C960965-00-v TITLE DOCUMENTNO. REV. Instrument& Control Specifications InstrumentList v049-l -036 0 E&lConstructionWork v049-2-022 0 PersonalComputers v049-2-049 0 BakeoutSystem Thermocouple v049-2-050 I MeasurementSystem T/C MeasurementPLC Interface v049-2-051 0 BakeoutPLC-TCInterface Soft ware v049-2-053 1 Functionality BakeoutSystem PC-PlC Interface v049-2-057 0 BakeoutSystem PC InterfaceSoftware v049-2-058 0 PitotTubes v049-2-079 0 DifferentialPressure Transmitlers v049-2-088 0 LevelTransmitters v049-2-089 0 PressureTransmitters v049-2-090 0 TemperatureElements v049-2-091 0 Interlocks,Permissives and Software AIarms v049-2-092 0 Material Specifications O-fungs v049-2-045 0 StainlessSteel Vessel Plate v049-2-041 1 StainlessSteel Flange Forgings v049-2-040 4 StainlessSteel Vessel Heads v049-2-039 3 LIGO VACUUM EQUIPMENT FINAL DESIGNREPORT CDRL 03 VOLUME TABLE OF CONTENT VOLUME TITLE VolumeI Project ManagementPlan VolumeII Design VolumeII AuachmentI Calculations VolumeII Attachment2 Calculations VolumeII Attachment3 Calculations Volumell Attachment4 Calculations VolumeII Attachment5 Specifications/Ir,lisc. -

Russian Olympic Champion Savinova Stripped of Gold

SPORTS SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2017 Wiesberger grabs lead after nine birdie blitz KUALA LUMPUR: Bernd Wiesberger reeled off with preferred lies in place, when players are do on the green today again which was nice,” added nine birdies in a row in a superb second round of allowed to improve the ball’s lie without penalty on the Austrian, who began the day six shots off lead. 63 to grab a one-shot lead over Masters champion certain parts of the course, the Austrian will not Englishman Willett hit six birdies and a bogey in Danny Willett at the Maybank Championship in make the record books. “I hit really good shots and I his 67 to sit at 11-under, two shots clear of Kuala Lumpur yesterday. The 31-year-old lit up the just felt calm out there,” he said after returning a Frenchman Mike Lorenzo-Vera and American Saujana Golf and Country Club with the birdie blitz card that included 11 birdies and two bogeys. “It felt David Lipsky. Lorenzo-Vera sank six birdies and an from the seventh to 15th holes to go 12-under kind of natural, I hit pretty good shots and really eagle in his 65, while Lipsky was bogey-free in his after 36 to boost his prospects of a fourth only holed two long ones which were the last birdie 67. Marc Warren of Scotland surrendered his European Tour title. of the nine on 15 and about a 20-footer on 11. overnight lead with a three-over-par round of 75, Wiesberger is the first player in European Tour “Apart from that I just hit them pretty close and felt following three bogeys and a triple bogey on his history to card nine straight birdies in a round but like I had a good idea of what the ball was going to last six holes. -

World Rankings — Women's

World Rankings — Women’s 800 1956 © TAKASHI ITO/PHOTO RUN 1 .......Lyudmila Gurevich (Soviet Union) 2 .............Nina Otkalenko (Soviet Union) 3 ............ Ursula Donath (East Germany) 4 ............. Phyllis Perkins (Great Britain) 5 ............... Diane Leather (Great Britain) 6 .............. Aida Lapshina (Soviet Union) 7 ..............Dzidra Levicka (Soviet Union) 8 ..........................Aranka Kazi (Hungary) 9 .......................... Halina Gabor (Poland) 10 ...............Betty Loakes (Great Britain) 1957 1 ............... Diane Leather (Great Britain) 2 ............ Ursula Donath (East Germany) 3 ... Yelizaveta Yermolayeva (Soviet Union) 4 .............Nina Otkalenko (Soviet Union) 5 ..............Dzidra Levicka (Soviet Union) 6 ........Tatyana Avramova (Soviet Union) 7 ..........................Florica Otel (Romania) 8 ..........................Aranka Kazi (Hungary) 9 .....................Gizella Sasvári (Hungary) 10 ..Bedřiška Kulhavá (Czechoslovakia) 1958 1 .Yelizaveta Yermolayeva (Soviet Union) 2 ............... Diane Leather (Great Britain) 3 ..............Dzidra Levicka (Soviet Union) 4 ........... Zoya Skobtsova (Soviet Union) 5 .............Nina Otkalenko (Soviet Union) 6 .......Lyudmila Gurevich (Soviet Union) 7 ............. Ariane Döser (West Germany) 8 ...........Vera Mukhanova (Soviet Union) 9 ................Dora Kozlova (Soviet Union) 10 ....Lyubov Yanvaryeva (Soviet Union) 1959 1 .......Lyudmila Gurevich (Soviet Union) 2 ..............Dzidra Levicka (Soviet Union) 3 ....................Joy Jordan (Great -

Capr-Toc 3..4

Cancer Prevention Contents Research January 2011 Volume 4 Number 1 PERSPECTIVES 51 Interleukin 6, but Not T Helper 2 Cytokines, Promotes Lung Carcinogenesis 1 The Search for Unaffected Individuals Cesar E. Ochoa, with Lynch Syndrome: Do the Ends Seyedeh Golsar Mirabolfathinejad, Justify the Means? Ana Ruiz Venado, Scott E. Evans, Heather Hampel and Albert de la Chapelle Mihai Gagea, Christopher M. Evans, See article by Dinh et al., p. 9 Burton F. Dickey, and Seyed Javad Moghaddam 6 Time to Think Outside the (Genetic) Box 65 Cannabinoid Receptors, CB1 and CB2, Jean-Pierre J. Issa and Judy E. Garber as Novel Targets for Inhibition of See article by Wong et al., p. 23 Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Growth and Metastasis RESEARCH ARTICLES Anju Preet, Zahida Qamri, Mohd W Nasser, Anil Prasad, Konstantin Shilo, Xianghong Zou, Jerome E. Groopman, 9 Health Benefits and Cost-Effectiveness and Ramesh K. Ganju of Primary Genetic Screening for Lynch Syndrome in the General Population 76 MicroRNAs 221/222 and Tuan A. Dinh, Benjamin I. Rosner, Genistein-Mediated Regulation of James C. Atwood, C. Richard Boland, ARHI Tumor Suppressor Gene in Sapna Syngal, Hans F. A. Vasen, Prostate Cancer Stephen B. Gruber, and Randall W. Burt Yi Chen, Mohd Saif Zaman, Guoren Deng, See perspective p. 1 Shahana Majid, Shranjot Saini, Jan Liu, Yuichiro Tanaka, and Rajvir Dahiya 23 Constitutional Methylation of the BRCA1 Promoter Is Specifically 87 Naftopidil, a Selective Associated with BRCA1 Mutation- a1-Adrenoceptor Antagonist, Associated Pathology in Early-Onset Suppresses Human Prostate Tumor Breast Cancer Growth by Altering Interactions Ee Ming Wong, Melissa C. -

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast?

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast? April 1988 NTIS order #PB88-212402 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Mapping Our Genes-The Genmne Projects.’ How Big, How Fast? OTA-BA-373 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1988). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 87-619898 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325 (order form can be found in the back of this report) Foreword For the past 2 years, scientific and technical journals in biology and medicine have extensively covered a debate about whether and how to determine the function and order of human genes on human chromosomes and when to determine the sequence of molecular building blocks that comprise DNA in those chromosomes. In 1987, these issues rose to become part of the public agenda. The debate involves science, technol- ogy, and politics. Congress is responsible for ‘(writing the rules” of what various Federal agencies do and for funding their work. This report surveys the points made so far in the debate, focusing on those that most directly influence the policy options facing the U.S. Congress, The House Committee on Energy and Commerce requested that OTA undertake the project. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, the Senate Com- mittee on Labor and Human Resources, and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natu- ral Resources also asked OTA to address specific points of concern to them. Congres- sional interest focused on several issues: ● how to assess the rationales for conducting human genome projects, ● how to fund human genome projects (at what level and through which mech- anisms), ● how to coordinate the scientific and technical programs of the several Federal agencies and private interests already supporting various genome projects, and ● how to strike a balance regarding the impact of genome projects on international scientific cooperation and international economic competition in biotechnology. -

Biallelic MUTYH Mutations Can Mimic Lynch Syndrome

European Journal of Human Genetics (2014) 22, 1334–1337 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/14 www.nature.com/ejhg SHORT REPORT Biallelic MUTYH mutations can mimic Lynch syndrome Monika Morak1,2, Barbara Heidenreich1, Gisela Keller3, Heather Hampel4, Andreas Laner2, Albert de la Chapelle4 and Elke Holinski-Feder*,1,2 The hallmarks of Lynch syndrome (LS) include a positive family history of colorectal cancer (CRC), germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, tumours with high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and loss of MMR protein expression. However, in B10–15% of clinically suspected LS cases, MMR mutation analyses cannot explain MSI-H and abnormal immunohistochemistry (IHC) results. The highly variable phenotype of MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) can overlap with the LS phenotype, but is inherited recessively. We analysed the MUTYH gene in 85 ‘unresolved’ patients with tumours showing IHC MMR-deficiency without detectable germline mutation. Biallelic p.(Tyr179Cys) MUTYH germline mutations were found in one patient (frequency 1.18%) with CRC, urothelial carcinoma and a sebaceous gland carcinoma. LS was suspected due to a positive family history of CRC and because of MSI-H and MSH2–MSH6 deficiency on IHC in the sebaceous gland carcinoma. Sequencing of this tumour revealed two somatic MSH2 mutations, thus explaining MSI-H and IHC results, and mimicking LS-like histopathology. This is the first report of two somatic MSH2 mutations leading to an MSI-H tumour lacking MSH2–MSH6 protein expression in a patient with MAP. In addition to typical transversion mutations in KRAS and APC, MAP can also induce tumourigenesis via the MSI-pathway. -

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Latent Class Analysis to Classify Patients with Transthyretin Amyloidosis by Signs and Symptoms

Neurol Ther DOI 10.1007/s40120-015-0028-y ORIGINAL RESEARCH Latent Class Analysis to Classify Patients with Transthyretin Amyloidosis by Signs and Symptoms Jose Alvir . Michelle Stewart . Isabel Conceic¸a˜o To view enhanced content go to www.neurologytherapy-open.com Received: February 21, 2015 Ó The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com ABSTRACT status measures for the latent classes were examined. Introduction: The aim of this study was to Results: A four-class latent class solution was develop an empirical approach to classifying thebestfitforthedata.Thelatentclasseswere patients with transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) characterized by the predominant symptoms based on clinical signs and symptoms. as severe neuropathy/severe autonomic, Methods: Data from 971 symptomatic subjects moderate to severe neuropathy/low to enrolled in the Transthyretin Amyloidosis moderate autonomic involvement, severe Outcomes Survey were analyzed using a latent cardiac, and moderate to severe neuropathy. class analysis approach. Differences in health Incorporating disease duration improved the model fit. It was found that measures of health Electronic supplementary material The online status varied by latent class in interpretable version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40120-015-0028-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to patterns. authorized users. Conclusion: This latent class analysis approach On behalf of the THAOS Investigators. offered promise in categorizing patients with ATTR across the spectrum of disease. The four- Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov number, class latent class solution included disease NCT00628745. duration and enabled better detection of J. Alvir (&) heterogeneity within and across genotypes Statistical Center for Outcomes, Real-World and than previous approaches, which have tended Aggregate Data, Global Medicines Development, Global Innovative Pharma Business, Pfizer, Inc., to classify patients a priori into neuropathic, New York, NY, USA cardiac, and mixed groups. -

The Future of Sex in Elite Sport

Sports science outlook ILLUSTRATION BY JONAS BERGSTRAND JONAS BY ILLUSTRATION n the excitement of leaving for the sex, based on chromosomes. People usually 1985 World University Games in Kobe, have 46 chromosomes arranged in 23 pairs. Japan, Spanish hurdler María José One of these pairs differs depending on the THE Martínez-Patiño forgot to pack her biological sex of the individual: women typi- doctor-issued ‘certificate of femininity’. cally have two X chromosomes, whereas men “You had to prove you were a woman in typically have an X and a Y. Genetic errors, FUTURE Iorder to compete,” she explains. Without it, mutations and interactions between DNA and she had to take a simple biological test. But hormones can, however, cause a panoply of it produced an unexpected result, and so exceptions to this arrangement. Although a she had to take a more thorough test — one person’s chromosomes might indicate one OF SEX that would take months to process. The team sex, their anatomy might suggest otherwise. physician advised her to fake an ankle injury This is known as intersex or differences of sex to silence suspicion around why she was not development (DSDs). IN ELITE running, so she sat in the stands with her foot The chromosome-based test required by bandaged and watched, wondering what the the IOC involved taking cells from inside the test result meant. cheek. In a cell containing two X chromo- SPORT Sport has a long history of policing who somes, one chromosome is inactive and there- counts as a woman. Blanket mandatory ‘sex fore shows up under the microscope as a dark Sex has long been used verification’ testing was put in place at events spot in the nucleus, known as a Barr body. -

Annona Coriacea Mart. Fractions Promote Cell Cycle Arrest and Inhibit Autophagic Flux in Human Cervical Cancer Cell Lines

molecules Article Annona coriacea Mart. Fractions Promote Cell Cycle Arrest and Inhibit Autophagic Flux in Human Cervical Cancer Cell Lines Izabela N. Faria Gomes 1,2, Renato J. Silva-Oliveira 2 , Viviane A. Oliveira Silva 2 , Marcela N. Rosa 2, Patrik S. Vital 1 , Maria Cristina S. Barbosa 3,Fábio Vieira dos Santos 3 , João Gabriel M. Junqueira 4, Vanessa G. P. Severino 4 , Bruno G Oliveira 5, Wanderson Romão 5, Rui Manuel Reis 2,6,7,* and Rosy Iara Maciel de Azambuja Ribeiro 1,* 1 Experimental Pathology Laboratory, Federal University of São João del Rei—CCO/UFSJ, Divinópolis 35501-296, Brazil; [email protected] (I.N.F.G.); [email protected] (P.S.V.) 2 Molecular Oncology Research Center, Barretos Cancer Hospital, Barretos 14784-400, Brazil; [email protected] (R.J.S.-O.); [email protected] (V.A.O.S.); [email protected] (M.N.R.) 3 Laboratory of Cell Biology and Mutagenesis, Federal University of São João del Rei—CCO/UFSJ, Divinópolis 35501-296, Brazil; [email protected] (M.C.S.B.); [email protected] (F.V.d.S.) 4 Special Academic Unit of Physics and Chemistry, Federal University of Goiás, Catalão 75704-020, Brazil; [email protected] (J.G.M.J.); [email protected] (V.G.P.S.) 5 Petroleomic and forensic chemistry laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Federal Institute of Espirito Santo, Vitória, ES 29075-910, Brazil; [email protected] (B.G.O.); [email protected] (W.R.) 6 Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), Medical School, University of Minho, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal 7 3ICVS/3B’s-PT Government Associate Laboratory, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.M.R.); [email protected] (R.I.M.d.A.R.); Tel.: +55-173-321-6600 (R.M.R.); +55-3736-904-484 or +55-3799-1619-155 (R.I.M.d.A.R.) Received: 25 September 2019; Accepted: 29 October 2019; Published: 1 November 2019 Abstract: Plant-based compounds are an option to explore and perhaps overcome the limitations of current antitumor treatments.