Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life & Games Akiva Rubinstein

The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein Volume 2: The Later Years Second Edition by John Donaldson & Nikolay Minev 2011 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein: The Later Years The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein Volume 2: The Later Years Second Edition ISBN: 978-1-936490-39-4 © Copyright 2011 John Donaldson and Nikolay Minev All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, elec- tronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the 2nd Edition 7 Rubinstein: 1921-1961 12 A Rubinstein Sampler 28 1921 Göteborg 29 The Hague 34 Triberg 44 1922 London 53 Hastings 62 Teplitz-Schönau 72 Vienna 83 1923 Hastings 96 Carlsbad 100 Mährisch-Ostrau 113 1924 Meran 120 Southport 129 Berlin 134 1925 London 137 Baden-Baden 138 Marienbad 153 Breslau 161 Moscow 165 3 The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein: The Later Years 1926 Semmering 176 Dresden 189 Budapest 196 Hannover 203 Berlin 207 1927 àyGĨ 212 Warsaw 221 1928 Bad Kissingen 223 Berlin 229 1929 Ramsgate 238 Carlsbad 242 Budapest 260 5RJDãND6ODWLQD 265 1930 San Remo 273 Antwerp (Belgian -

Opening Moves - Player Facts

DVD Chess Rules Chess puzzles Classic games Extras - Opening moves - Player facts General Rules The aim in the game of chess is to win by trapping your opponent's king. White always moves first and players take turns moving one game piece at a time. Movement is required every turn. Each type of piece has its own method of movement. A piece may be moved to another position or may capture an opponent's piece. This is done by landing on the appropriate square with the moving piece and removing the defending piece from play. With the exception of the knight, a piece may not move over or through any of the other pieces. When the board is set up it should be positioned so that the letters A-H face both players. When setting up, make sure that the white queen is positioned on a light square and the black queen is situated on a dark square. The two armies should be mirror images of one another. Pawn Movement Each player has eight pawns. They are the least powerful piece on the chess board, but may become equal to the most powerful. Pawns always move straight ahead unless they are capturing another piece. Generally pawns move only one square at a time. The exception is the first time a pawn is moved, it may move forward two squares as long as there are no obstructing pieces. A pawn cannot capture a piece directly in front of him but only one at a forward angle. When a pawn captures another piece the pawn takes that piece’s place on the board, and the captured piece is removed from play If a pawn gets all the way across the board to the opponent’s edge, it is promoted. -

Floridachess Summer 2019

Summer 2019 GM Olexandr Bortnyk wins the 26th Space Coast Open FCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS [term till] kqrbn Contents KQRBN President Kevin J. Pryor (NE) [2019] Editor Speaks & President’s Message .................................................................... 3 Jacksonville, FL [email protected] FCA’s Membership Growth .......................................................................................... 4 FCA Elections ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vice President Ukrainian Takes Over Space Coast Open by Peter Dyson .................................. 5 Stephen Lampkin (NE) [2019] Port Orange, FL Space Coast Open Brilliancy Prize winners by Javad Maharramzade .............. 5 [email protected] 2019 CFCC Sunshine Open by Steven Vigil ............................................................... 10 by Miguel Ararat ................................................. Secretary Some games from recent events 12 Bryan Tillis (S) [2019] A game from the 26th Space Coast Open ............................................................. 16 West Palm Beach, FL Meet the Candidates .........................................................................................................19 [email protected] 2019 FCA Voting Procedures .......................................................................................19 Treasurer 2019 Queen’s Cup Challenge by Kevin Pryor .............................................................. 20 Scott -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

A Book About Razuvaev.Indb

Compiled by Boris Postovsky Devoted to Chess The Creative Heritage of Yuri Razuvaev New In Chess 2019 Contents Preface – From the compiler . 7 Foreword – Memories of a chess academic . 9 ‘Memories’ authors in alphabetical order . 16 Chapter 1 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – I . 17 Garry Kasparov . 17 Anatoly Karpov . 19 Boris Spassky . 20 Veselin Topalov . .22 Viswanathan Anand . 23 Magnus Carlsen . 23 Boris Postovsky . 23 Chapter 2 – Selected games . 43 1962-1973 – the early years . 43 1975-1978 – grandmaster . 73 1979-1982 – international successes . 102 1983-1986 – expert in many areas . 138 1987-1995 – always easy and clean . 168 Chapter 3 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – II . 191 Evgeny Tomashevsky . 191 Boris Gulko . 199 Boris Gelfand . 201 Lyudmila Belavenets . 202 Vladimir Tukmakov . .202 Irina Levitina . 204 Grigory Kaidanov . 206 Michal Krasenkow . 207 Evgeny Bareev . 208 Joel Lautier . 209 Michele Godena . 213 Alexandra Kosteniuk . 215 5 Devoted to Chess Chapter 4 – Articles and interviews (by and with Yuri Razuvaev) . 217 Confessions of a grandmaster . 217 My Gambit . 218 The Four Knights Opening . 234 The gambit syndrome . 252 A game of ghosts . 258 You are right, Monsieur De la Bourdonnais!! . 267 In the best traditions of the Soviet school of chess . 276 A lesson with Yuri Razuvaev . 283 A sharp turn . 293 Extreme . 299 The Botvinnik System . 311 ‘How to develop your intellect’ . 315 ‘I am with Tal, we all developed from Botvinnik . ’. 325 Chapter 5 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – III . .331 Igor Zaitsev . 331 Alexander Nikitin . 332 Albert Kapengut . 332 Alexander Shashin . 335 Boris Zlotnik . 337 Lev Khariton . 337 Sergey Yanovsky . -

FIDE Trainers Committee V22.1.2005

FIDE Training! Don’t miss the action! by International Master Jovan Petronic Chairman, FIDE Computer & Internet Chess Committee In 1998 FIDE formed a powerful Committee comprising of leading chess trainers around the chess globe. Accordingly, it was named the FIDE Trainers Committee, and below, I will try to summarize the immense useful information for the readers, current major chess training activities and appeals of the Committee, etc. Among their main tasks in the period 1998-2002 were FIDE licensing of chess trainers and the recognition of these by the International Olympic Committee, benefiting in the long run, to all chess federations, trainers and their students. The proven benefits of playing and studying chess have led to countries, such as Slovenia, introducing chess into their compulsory school curiccullum! The ASEAN Chess Academy, headed by FIDE Vice President, FM, IA & IO - Ignatius Leong, has organized from November 7th to 14th 2003 - a Training Course under the auspices of FIDE and the International Olympic Committee! IM Nikola Karaklajic from Serbia & Montenegro provided the training. The syllabus was targeted for middle and lower levels. At the time, the ASEAN Chess Academy had a syllabus for 200 lessons of 90 minutes each! I am personally proud of having completed such a Course in Singapore. You may view the official Certificate I received here. Another Trainers’ Course was conducted by FIDE and the Asean Chess Academy from 12th to 17th December 2004! Extensive testing was done, here is the list of the candidates who had passed the FIDE Trainer high criteria! The main lecturer was FIDE Senior Trainer Israel Gelfer. -

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion Isaak & Vladimir Linder Foreword by Andy Soltis Game Annotations by Karsten Müller World Chess Champions Series 2020 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion ISBN: 978-1-949859-16-4 (print) ISBN: 949859-17-1 (eBook) © Copyright 2020 Vladimir Linder All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Janel Lowrance Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword by Andy Soltis Signs and Symbols Everything about the World Championships Prologue Chapter 1 His Life and Fate His Childhood and Youth His Family His Personality His Student Life The Algorithm of Mastery The School of the Young and Gifted Political Survey Guest Appearances Curiosities The Netherlands Great Britain Chapter 2 Matches, Tournaments, and Opponents AVRO Tournament, 1938 Alekhine-Botvinnik: The Match That Did Not Happen Alekhine Memorial, 1956 Amsterdam, 1963 and 1966 Sergei Belavienets Isaak Boleslavsky Igor Bondarevsky David Bronstein Wageningen, 1958 Wijk aan Zee, 1969 World Olympiads -

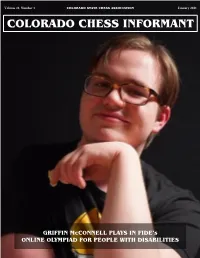

January 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 1 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION January 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT GRIFFIN McCONNELL PLAYS IN FIDE’s ONLINE OLYMPIAD FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Volume 48, Number 1 Colorado Chess Informant January 2021 From the Editor And so we begin the New Year with renewed hope that can only arrive none too soon... Hello everyone and Happy New Year! I hope that you have en- joyed the holiday season as much as you can and that you are safe and as happy as can be. I understand that a few of our fellow The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a Colorado chess players have been afflicted with Covid-19 but as Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- I understand, they are all on the road to recovery or have already tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are healed up and are back at life full tilt. tax deductible. As you can read in this issue, the CSCA Board of Directors are Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) working hard to at least plan on having some in-person tourna- memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to ments held this year. We all hope that it does indeed come to additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- pass - so stay tuned. tic tournament membership is available for $3. The lead story in this issue is about a remarkable young man and ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the his wonderful play at FIDE’s Online Olympiad for People with email address [email protected]. -

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012)

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012) EUROPEAN CHESS UNION WON THE COURT CASE AGAINST TURKISH CHESS FEDERATION IN CAS In October 2011, the Turkish Chess Federation filed an Appeal at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) against the decision of the ECU concerning the award of competitions during the bidding procedure for 2013. According to the Appeal by the Turkish Chess Federation, the decision to award the European Youth Championship 2013 to the organizer from Budva, Montenegro was illegal. Also, the Appellant believed that they should have been awarded the organization of the European Senior Team Championship 2013 directly. In the arbitration between the Turkish Chess Federation and the European Chess Union, the CAS and the Panel of three Arbitrators presided by Mr. Robert Reid from England delivered the Arbitral Award on March 22, 2012. The Appeal filed by the Turkish Chess Federation was dismissed, while the decisions made by the European Chess Union Board were accepted as valid. In addition, according to CAS, ‘the costs of the arbitration... shall be borne by the Appellant’. You can download the complete Arbitral Award from the ECU web site. Official web site: http://www.europechess.net/ © Europechess.net Page 1 EUROPEAN CHESS UNION BOARD MEETING IN PLOVDIV The European Chess Union Board meeting was held in "Novotel" hotel in Plovdiv during the European Individual Chess Championship. The main topic of the meeting was the endorsement of the Written Declaration ‘Chess in School’ in the European Parliament. ECU President Silvio Danailov thanked the Board members and others who helped the Declaration to be adopted. -

July 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 3 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION July 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT BACK TO “NEARLY NORMAL” OVER-THE-BOARD PLAY Volume 48, Number 3 Colorado Chess Informant July 2021 From the Editor Slowly, we are getting there... Only fitting that the return to over-the-board tournament play in Colorado resumed with the Senior Open this year. If you recall, that was the last over-the-board tournament held before we went into lockdown last year. You can read all about this year’s offer- The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a ing on page 12. Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- The Denver Chess Club has resumed activity (read the resump- tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are tive result on page 8) with their first OTB tourney - and it went tax deductible. like gang-busters. So good to see. They are also resuming their Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) club play in August. Check out the latest with them at memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to www.DenverChess.com. additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- And if you look at the back cover you will see that the venerable tic tournament membership is available for $3. Colorado Open has returned in all it’s splendor! Somehow I ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the think that this maybe the largest turnout so far - just a hunch on email address [email protected]. my part as players in this state are so hungry to resume the tour- ● Send pay renewals & memberships to the CSCA. -

Eric Schiller the Rubinstein Attack!

The Rubinstein Attack! A chess opening strategy for White Eric Schiller The Rubinstein Attack: A Chess Opening Strategy for White Copyright © 2005 Eric Schiller All rights reserved. BrownWalker Press Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2005 ISBN: 1-58112-454-6 BrownWalker.com If you are looking for an effective chess opening strategy to use as White, this book will provide you with everything you need to use the Rubinstein Attack to set up aggressive attacking formations. Building on ideas developed by the great Akiba Rubinstein, this book offers an opening system for White against most Black defensive formations. The Rubinstein Attack is essentially an opening of ideas rather than memorized variations. Move order is rarely critical, the flow of the game will usually be the same regardless of initial move order. As you play through the games in this book you will see each of White’s major strategies put to use against a variety of defensive formations. As you play through the games in this book, pay close attention to the means White uses to carry out the attack. You’ll see the same patterns repeated over and over again, and you can use these stragies to break down you opponent’s defenses. The basic theme of each game is indicated in the title in the game header. The Rubinstein is a highly effective opening against most defenses to 1.d4, but it is not particularly effective against the King’s Indian or Gruenfeld formations. To handle those openings, you’ll need to play c4 and enter some of the main lines, though you can choose solid formations with a pawn at d3. -

José Raúl Capablanca Y Graupera 3Rd Classical World Champ from 1921-1927

José Raúl Capablanca y Graupera 3rd classical world champ from 1921-1927 José Raúl Capablanca, y Graupera (19 November 1888 – 8 March 1942) nicknamed “The Human Chess Machine, was a Cuban chess player who was world chess champion from 1921 to 1927. A chess prodigy, he is considered by many as one of the greatest players of all time, widely renowned for his exceptional endgame skill and speed of play. His skill in rapid chess lent itself to simultaneous exhibitions. José Raúl Capablanca, the second surviving son of a Spanish army officer,[3] was born in Havana on November 19, 1888.[4] According to Capablanca, he learned to play chess at the age of four by watching his father play with friends, pointed out an illegal move by his father, and then beat his father.[5] Between November and December 1901, he beat Cuban champion Juan Corzo in a match on 17 November 1901, two days before his 13th birthday.[1][2] However, in April 1902 he came in fourth out of six in the National Championship, losing both his games with Corzo.[7] In 1905 Capablanca joined the Manhattan Chess Club, and was soon recognized as the club's strongest player.[4] He was particularly dominant in rapid chess, winning a tournament ahead of the reigning World Chess Champion, Emanuel Lasker, in 1906.[4] He represented Columbia on top board in intercollegiate team chess.[8] In 1908 he left the university to concentrate on chess.[4][6] His victory over Frank Marshall in a 1909 match earned him an invitation to the 1911 San Sebastian tournament, which he won ahead of players such as Akiba Rubinstein, Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch.