Sacrococcygeal Teratoma in the Perinatal Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Sacrum to Spine: a Complex Case of Sacrococcygeal Teratoma

From Sacrum to Spine: A Complex Case of Sacrococcygeal Teratoma Jennifer Young, MN, RN(EC) NP-Pediatrics, NNP-BC Hazel Pleasants-Terashita, MN, RN(EC) NP-Pediatrics, NNP-BC Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) ABSTRACT Credit The test questions are pro- Neonatal tumors occur infrequently; sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is a rare and abnormal mass vided in this issue. The often diagnosed on antenatal ultrasound. An SCT may cause serious antenatal complications, requires posttest and evaluation must be com- surgery in the neonatal period, and can lead to various long-term sequelae including fecal incontinence pleted online. Details to complete the course are provided online at acade- or constipation, urinary incontinence, and lower extremity mobility impairment. Even rarer are SCTs myonline.org. Sign into your ANN that include intraspinal extension necessitating complex neurosurgical intervention to relieve possible account or register for a non-member spinal cord compression or tumor tissue resection. A comprehensive understanding of the natural account if you are not a member. A total of 1.5 contact hour(s) can be earned as history of SCT provides frontline neonatal nurses and nurse practitioners with the expertise and CNE credit for reading this article, language to support families during an infant’s NICU admission. A glossary of key terms accompanied studying the content, and completing the online posttest and evaluation. To by a case review of a premature infant born with a large external SCT with intrapelvic and intraspinal be successful, the learner must obtain a components aids in enhancing knowledge related to the potential impact of an SCT on the central grade of at least 80 percent on the test. -

Hyperplasia (Growth Factors

Adaptations Robbins Basic Pathology Robbins Basic Pathology Robbins Basic Pathology Coagulation Robbins Basic Pathology Robbins Basic Pathology Homeostasis • Maintenance of a steady state Adaptations • Reversible functional and structural responses to physiologic stress and some pathogenic stimuli • New altered “steady state” is achieved Adaptive responses • Hypertrophy • Altered demand (muscle . hyper = above, more activity) . trophe = nourishment, food • Altered stimulation • Hyperplasia (growth factors, . plastein = (v.) to form, to shape; hormones) (n.) growth, development • Altered nutrition • Dysplasia (including gas exchange) . dys = bad or disordered • Metaplasia . meta = change or beyond • Hypoplasia . hypo = below, less • Atrophy, Aplasia, Agenesis . a = without . nourishment, form, begining Robbins Basic Pathology Cell death, the end result of progressive cell injury, is one of the most crucial events in the evolution of disease in any tissue or organ. It results from diverse causes, including ischemia (reduced blood flow), infection, and toxins. Cell death is also a normal and essential process in embryogenesis, the development of organs, and the maintenance of homeostasis. Two principal pathways of cell death, necrosis and apoptosis. Nutrient deprivation triggers an adaptive cellular response called autophagy that may also culminate in cell death. Adaptations • Hypertrophy • Hyperplasia • Atrophy • Metaplasia HYPERTROPHY Hypertrophy refers to an increase in the size of cells, resulting in an increase in the size of the organ No new cells, just larger cells. The increased size of the cells is due to the synthesis of more structural components of the cells usually proteins. Cells capable of division may respond to stress by undergoing both hyperrtophy and hyperplasia Non-dividing cell increased tissue mass is due to hypertrophy. -

Acquired Tumors Arising from Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium

CLINICAL SCIENCES Acquired Tumors Arising From Congenital Hypertrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Jerry A. Shields, MD; Carol L. Shields, MD; Arun D. Singh, MD Background: Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal lacunae in all 5 patients. The CHRPE ranged in basal di- pigment epithelium (CHRPE) is widely recognized to ameter from 333mmto13311 mm. The size of the el- be a flat, stationary condition. Although it can show evated lesion ranged from 23232mmto83834 mm. minimal increase in diameter, it has not been known to The nodular component in all cases was supplied and spawn nodular tumor that is evident ophthalmoscopi- drained by slightly prominent, nontortuous retinal blood cally. vessels. Yellow retinal exudation occurred adjacent to the nodule in all 5 patients and 1 patient developed a second- Objectives: To report 5 cases of CHRPE that gave rise ary retinal detachment. Two tumors that showed progres- to an elevated lesion and to describe the clinical features sive enlargement, increasing exudation, and progressive of these unusual nodules. visual loss were treated with iodine 125–labeled plaque brachytherapy, resulting in deceased tumor size but no im- Methods: Retrospective medical record review. provement in the visual acuity. Results: Of 5 patients with a nodular lesion arising from Conclusions: Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pig- CHRPE, there were 4 women and 1 man, 4 whites and 1 ment epithelium can spawn a nodular growth that slowly black. Three patients were followed up for typical CHRPE enlarges, attains a retinal blood supply, and causes exuda- for longer than 10 years before the tumor developed; 2 pa- tiveretinopathyandchroniccystoidmacularedema.Although tients were recognized to have CHRPE and the elevated no histopathologic evidence is yet available, we believe that tumor concurrently. -

Sacrococcygeal Teratoma and Normal Alphafetoprotein Concentration on September 26, 2021 by Guest

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.22.5.405 on 1 October 1985. Downloaded from Case reports 405 Lymphocyte studies revealed the mother's band has been incorporated into another breakpoint chromosomes to be normal. The father was unavail- site. The smallness of the deleted segment may able for study. explain her minimal dysmorphogenetic features; however, there is a lack of clinical similarity Discussion between our patient and the other two cases of interstitial 2p deletions. For example, our patient The clinical features of patients with deletions of 2p had premature closure of her fontanelles, whereas are summarised in the table. The patient of three other patients, including one with a deleted Ferguson-Smith et at2 is not included in the tabula- segment incorporating band 2p14,4 had delayed tion because he was also partially trisomic for the closure of their fontanelles. It is possible that our distal four bands of Sq and so was not a pure case of patient's physical and mental stigmata are the partial 2p monosomy. The patient reported by consequence of a disruption in one or more gene's Zachai et at5 is identical to case 2 of Emanuel et al. 1 nucleotide sequence resulting from this child's Given the paucity of reported cases, only the most numerous chromosome breaks. Given the uncer- tentative statements can be made regarding the tainty of our patient's karyotype and the limited clinical picture associated with deletions of 2p. The number of 2p deletion cases, it is evident that more Iwo cases presented by Emanuel et all have nearly cases of 2p deletions are required before a clear cut identical deleted segments and share the following 2p deletion syndrome, or syndromes, emerges. -

Chapter 1 Cellular Reaction to Injury 3

Schneider_CH01-001-016.qxd 5/1/08 10:52 AM Page 1 chapter Cellular Reaction 1 to Injury I. ADAPTATION TO ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS A. Hypertrophy 1. Hypertrophy is an increase in the size of an organ or tissue due to an increase in the size of cells. 2. Other characteristics include an increase in protein synthesis and an increase in the size or number of intracellular organelles. 3. A cellular adaptation to increased workload results in hypertrophy, as exemplified by the increase in skeletal muscle mass associated with exercise and the enlargement of the left ventricle in hypertensive heart disease. B. Hyperplasia 1. Hyperplasia is an increase in the size of an organ or tissue caused by an increase in the number of cells. 2. It is exemplified by glandular proliferation in the breast during pregnancy. 3. In some cases, hyperplasia occurs together with hypertrophy. During pregnancy, uterine enlargement is caused by both hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the smooth muscle cells in the uterus. C. Aplasia 1. Aplasia is a failure of cell production. 2. During fetal development, aplasia results in agenesis, or absence of an organ due to failure of production. 3. Later in life, it can be caused by permanent loss of precursor cells in proliferative tissues, such as the bone marrow. D. Hypoplasia 1. Hypoplasia is a decrease in cell production that is less extreme than in aplasia. 2. It is seen in the partial lack of growth and maturation of gonadal structures in Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome. E. Atrophy 1. Atrophy is a decrease in the size of an organ or tissue and results from a decrease in the mass of preexisting cells (Figure 1-1). -

Cancer Research and Reports an Open Access Journal CRR-1-E102

Cancer Research and Reports An open access journal CRR-1-e102 Editorial Paediatric Gynaecologic Neoplasms Abdelrahman K Hanafy, Priya R Bhosale, Ajaykumar C Morani* Departments of Diagnostic Radiology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA Introduction common than mature teratomas. Degree of malignancy is determined based on the level of neuroectodermal component A variety of gynaecologic neoplasms occur in the pediatric differentiation in tissue samples [11]. Teratomas can also occur population. Differentiating between benign and malignant extragonadal; the important one which needs a particular lesions and reaching the correct diagnosis in a timely manner is mention includes sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT). SCT is the crucial to preserve fertility, which is a priority in this most common teratoma in neonates, and often detected on population. Awareness of the clinical, laboratory and pertinent prenatal US. Most SCTs are benign at birth; however, imaging characteristics of such lesions will facilitate their malignant transformation can occur. Associated anorectal and recognition in clinical practice. genitourinary malformations may also occur. MRI is the best modality for depicting this lesion and evaluating surrounding Ovarian neoplasms structures for invasion. After resection of SCT, surveillance for recurrence is recommended for 3 years utilizing a combination Ovarian tumors are uncommon in childhood having an of physical exam, AFP levels and periodic pelvic imaging [12- incidence of 2.6 /100,000 girls per year. Majority of these are 14]. Dysgerminoma is the most common malignant ovarian benign; less than one third are malignant [1,2]. Presentation is germ cell tumor (MOGCT). On MRI, it appears as a solid usually as a palpable mass or abdominal pain. -

ULTRASOUND STUDY GUIDE • Technical Knowledge O Physics And

ULTRASOUND STUDY GUIDE Technical knowledge o Physics and Safety, understand the following: 1) Physics of sound interactions in the body. 2) How transducers work, how the image is created, and what physical properties are being displayed. 3) Relative strengths and weaknesses of different transducers including various aspects of resolution. Sound properties and interactions Reflection Attenuation Scattering Refraction Absorption Acoustic impedance Speed of sound Wavelength Other . Transducer fundamentals Transmit frequencies Transducer components Transducer types Transducer pros and cons Other . Beam formation Focusing Steering Other . Imaging modes and display 2D 3D 4D Panoramic imaging Compound imaging Harmonic imaging Elastography Contrast imaging Scanning modes o 2D o 3D o 4D o M-mode o Doppler o Other Image orientation Other . Image resolution Axial Lateral Elevational / Azimuthal Temporal Contrast Penetration vs. resolution Other . System Controls - Know the function of the controls listed below and be able to recognize them in the list of scan parameters shown on the image monitor Gain Time gain compensation Power output Focal zone Transmit frequency Depth Width Zoom / Magnification Dynamic range Frame rate Line density Frame averaging / persistence Other . Doppler / Flow imaging – Be familiar with the terminology used to describe Doppler exams. Be able to interpret and optimize the images. Be able to recognize artifacts, know their significance, and know what produces them. Doppler -

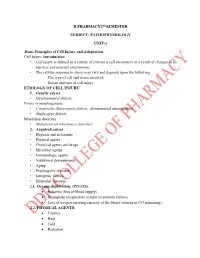

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY UNIT-1 .Basic Principles of Cell Injury And

B.PHARMACY2nd SEMESTER SUBJECT: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY UNIT-1 .Basic Principles of Cell Injury and Adaptation Cell Injury: Introduction • Cell injury is defined as a variety of stresses a cell encounters as a result of changes in its internal and external environment. • The cellular response to stress may vary and depends upon the following: – The type of cell and tissue involved. – Extent and type of cell injury. ETIOLOGY OF CELL INJURY: 1. Genetic causes • Developmental defects: Errors in morphogenesis • Cytogenetic (Karyotypic) defects: chromosomal abnormalities • Single-gene defects: Mendelian disorders • Multifactorial inheritance disorders. 2. Acquired causes • Hypoxia and ischaemia • Physical agents • Chemical agents and drugs • Microbial agents • Immunologic agents • Nutritional derangements • Aging • Psychogenic diseases • Iatrogenic factors • Idiopathic diseases. 2.1. Oxygen deprivation: HYPOXIA Ischemia (loss of blood supply). Inadequate oxygenation (cardio respiratory failure). Loss of oxygen carrying capacity of the blood (anemia or CO poisoning). 2.2. PHYSICAL AGENTS: Trauma Heat Cold Radiation Electric shock 2.3. CHEMICAL AGENTS AND DRUGS: Endogenous products: urea, glucose Exogenous agents Therapeutic drugs: hormones Nontherapeutic agents: lead or alcohol. 2.4. INFECTIOUS AGENTS: Viruses Rickettsiae Bacteria Fungi Parasites 2.5. Abnormal immunological reactions: The immune process is normally protective but in certain circumstances the reaction may become deranged. Hypersensitivity to various substances can lead to anaphylaxis or to more localized lesions such as asthma. In other circumstances the immune process may act against the body cells – autoimmunity. 2.6. Nutritional imbalances: Protein-calorie deficiencies are the most examples of nutrition deficiencies. Vitamins deficiency. Excess in nutrition are important causes of morbidity and mortality. Excess calories and diet rich in animal fat are now strongly implicated in the development of atherosclerosis. -

Obstetrics and Gynecology Practice Analysis Detailed Report

Obstetrics and Gynecology Practice Analysis Detailed Report ARDMS approved March 2021. CONFIDENTIALITY NOTICE The information contained within this report is confidential and is for the exclusive use for Inteleos. No redistribution or subsequent disclosure of this document is permitted without prior authorization from Inteleos. OB/GYN Practice Analysis Report Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................ 4 BACKGROUND OF STUDY .......................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Selection and Profile of Subject Matter Experts ............................................................................................ 4 Workshop Panel .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Remote Panel ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Panelist Interviews and Workshop .................................................................................................................... -

Somatic Events Modify Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Pathology and Link Hypertrophy to Arrhythmia

Somatic events modify hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology and link hypertrophy to arrhythmia Cordula M. Wolf*†, Ivan P. G. Moskowitz†‡§¶, Scott Arno‡, Dorothy M. Branco*, Christopher Semsarian‡§ʈ, Scott A. Bernstein**, Michael Peterson‡¶, Michael Maida‡, Gregory E. Morley**, Glenn Fishman**, Charles I. Berul*, Christine E. Seidman‡§††‡‡, and J. G. Seidman‡§†† Departments of *Cardiology and ¶Pathology, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115; ‡Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; §Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston, MA 02115; and **Department of Cardiology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10010 Contributed by Christine E. Seidman, October 19, 2005 Sarcomere protein gene mutations cause hypertrophic cardiomy- many HCM patients who succumb to ventricular arrhythmias all opathy (HCM), a disease with distinctive histopathology and in- of these risk factors are absent (11–13). creased susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias and risk for sudden Increased myocardial fibrosis and abnormal myocyte archi- death. Myocyte disarray (disorganized cell–cell contact) and car- tecture are associated with arrhythmia vulnerability in many diac fibrosis, the prototypic but protean features of HCM histopa- cardiovascular diseases (14–16), and these parameters are hy- thology, are presumed triggers for ventricular arrhythmias that pothesized to also increase sudden death risk in HCM (12, 17). precipitate sudden death events. To assess relationships between In support of this suggestion, histopathological studies -

View Showed Solid Tissue Fragments Composed of Mature Neural Tissue Comprising Glial Cells and Astrocytes with No Other Germ Cell Layer Component

Saadaat et al. Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2019) 2:24 Surgical and Experimental https://doi.org/10.1186/s42047-019-0049-4 Pathology CASE REPORT Open Access Brain ectopic tissue in sacrococcygeal region of a child, clinically mimicking sacrococcygeal teratoma: a case report Ramin Saadaat1, Jamshid Abdul-Ghafar1*, Ahmed Nasir2, Soma Rahmani2 and Hidayatullah Hamidi2 Abstract Background: Mature brain heterotopic tissue in sacrococcygeal region is a very rare benign congenital abnormality of newborn. To date, only two cases of mature heterotopic brain tissue in the sacrococcygeal region is reported by literature. Heterotopic brain tissue in other areas such as lung, nose, face and retroperitoneal region are also rarely reported. Meanwhile, rather than brain heterotopic tissue in sacrococcygeal region, a case of adrenal gland heterotopic tissue in sacrococcygeal region also has been reported. Case presentation: A 3.5 month-old male baby presented with history of sacrococcygeal mass since birth. Clinical examination of the child was good with no other problem. Sacrococcygeal region revealed an elevated round mass with no discharge. Computed tomography reported a large sacrococcygeal teratoma type-III arising from the sacrococcygeal region extending intra-abdominally to the level of L2 vertebral body. The mass was excised by the impression of sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT). On gross examination, a gray-white irregular tissue fragment with 5 cm in greatest dimension was examined. Cut sections showed homogenous yellowish white appearance. Histological examination revealed solid fragments composed of mature neural tissue comprising glial cells and astrocytes with no other germ cell layer component. Conclusion: Mature brain heterotopic tissue in sacrococcygeal area is a rare benign disease. -

The Repair of Skeletal Muscle Requires Iron Recycling Through Macrophage Ferroportin Gianfranca Corna, Imma Caserta, Antonella Monno, Pietro Apostoli, Angelo A

The Repair of Skeletal Muscle Requires Iron Recycling through Macrophage Ferroportin Gianfranca Corna, Imma Caserta, Antonella Monno, Pietro Apostoli, Angelo A. Manfredi, Clara Camaschella and This information is current as Patrizia Rovere-Querini of September 25, 2021. J Immunol 2016; 197:1914-1925; Prepublished online 27 July 2016; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501417 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/5/1914 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2016/07/26/jimmunol.150141 Material 7.DCSupplemental http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 53 articles, 16 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/5/1914.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 25, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2016 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology The Repair of Skeletal Muscle Requires Iron Recycling through Macrophage Ferroportin Gianfranca Corna,* Imma Caserta,*,† Antonella Monno,* Pietro Apostoli,‡ Angelo A.