Cubics Passing Through the Foci of an Inscribed Conic 1 Inconics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orthocorrespondence and Orthopivotal Cubics

Forum Geometricorum b Volume 3 (2003) 1–27. bbb FORUM GEOM ISSN 1534-1178 Orthocorrespondence and Orthopivotal Cubics Bernard Gibert Abstract. We define and study a transformation in the triangle plane called the orthocorrespondence. This transformation leads to the consideration of a fam- ily of circular circumcubics containing the Neuberg cubic and several hitherto unknown ones. 1. The orthocorrespondence Let P be a point in the plane of triangle ABC with barycentric coordinates (u : v : w). The perpendicular lines at P to AP , BP, CP intersect BC, CA, AB respectively at Pa, Pb, Pc, which we call the orthotraces of P . These orthotraces 1 lie on a line LP , which we call the orthotransversal of P . We denote the trilinear ⊥ pole of LP by P , and call it the orthocorrespondent of P . A P P ∗ P ⊥ B C Pa Pc LP H/P Pb Figure 1. The orthotransversal and orthocorrespondent In barycentric coordinates, 2 ⊥ 2 P =(u(−uSA + vSB + wSC )+a vw : ··· : ···), (1) Publication Date: January 21, 2003. Communicating Editor: Paul Yiu. We sincerely thank Edward Brisse, Jean-Pierre Ehrmann, and Paul Yiu for their friendly and valuable helps. 1The homography on the pencil of lines through P which swaps a line and its perpendicular at P is an involution. According to a Desargues theorem, the points are collinear. 2All coordinates in this paper are homogeneous barycentric coordinates. Often for triangle cen- ters, we list only the first coordinate. The remaining two can be easily obtained by cyclically permut- ing a, b, c, and corresponding quantities. Thus, for example, in (1), the second and third coordinates 2 2 are v(−vSB + wSC + uSA)+b wu and w(−wSC + uSA + vSB )+c uv respectively. -

Cevians, Symmedians, and Excircles Cevian Cevian Triangle & Circle

10/5/2011 Cevians, Symmedians, and Excircles MA 341 – Topics in Geometry Lecture 16 Cevian A cevian is a line segment which joins a vertex of a triangle with a point on the opposite side (or its extension). B cevian C A D 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 2 Cevian Triangle & Circle • Pick P in the interior of ∆ABC • Draw cevians from each vertex through P to the opposite side • Gives set of three intersecting cevians AA’, BB’, and CC’ with respect to that point. • The triangle ∆A’B’C’ is known as the cevian triangle of ∆ABC with respect to P • Circumcircle of ∆A’B’C’ is known as the evian circle with respect to P. 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 3 1 10/5/2011 Cevian circle Cevian triangle 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 4 Cevians In ∆ABC examples of cevians are: medians – cevian point = G perpendicular bisectors – cevian point = O angle bisectors – cevian point = I (incenter) altitudes – cevian point = H Ceva’s Theorem deals with concurrence of any set of cevians. 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 5 Gergonne Point In ∆ABC find the incircle and points of tangency of incircle with sides of ∆ABC. Known as contact triangle 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 6 2 10/5/2011 Gergonne Point These cevians are concurrent! Why? Recall that AE=AF, BD=BF, and CD=CE Ge 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 7 Gergonne Point The point is called the Gergonne point, Ge. Ge 05-Oct-2011 MA 341 001 8 Gergonne Point Draw lines parallel to sides of contact triangle through Ge. -

The Isogonal Tripolar Conic

Forum Geometricorum b Volume 1 (2001) 33–42. bbb FORUM GEOM The Isogonal Tripolar Conic Cyril F. Parry Abstract. In trilinear coordinates with respect to a given triangle ABC,we define the isogonal tripolar of a point P (p, q, r) to be the line p: pα+qβ+rγ = 0. We construct a unique conic Φ, called the isogonal tripolar conic, with respect to which p is the polar of P for all P . Although the conic is imaginary, it has a real center and real axes coinciding with the center and axes of the real orthic inconic. Since ABC is self-conjugate with respect to Φ, the imaginary conic is harmonically related to every circumconic and inconic of ABC. In particular, Φ is the reciprocal conic of the circumcircle and Steiner’s inscribed ellipse. We also construct an analogous isotomic tripolar conic Ψ by working with barycentric coordinates. 1. Trilinear coordinates For any point P in the plane ABC, we can locate the right projections of P on the sides of triangle ABC at P1, P2, P3 and measure the distances PP1, PP2 and PP3. If the distances are directed, i.e., measured positively in the direction of −→ −→ each vertex to the opposite side, we can identify the distances α =PP1, β =PP2, −→ γ =PP3 (Figure 1) such that aα + bβ + cγ =2 where a, b, c, are the side lengths and area of triangle ABC. This areal equation for all positions of P means that the ratio of the distances is sufficient to define the trilinear coordinates of P (α, β, γ) where α : β : γ = α : β : γ. -

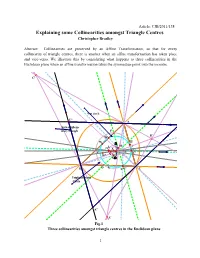

Explaining Some Collinearities Amongst Triangle Centres Christopher Bradley

Article: CJB/2011/138 Explaining some Collinearities amongst Triangle Centres Christopher Bradley Abstract: Collinearities are preserved by an Affine Transformation, so that for every collinearity of triangle centres, there is another when an affine transformation has taken place and vice-versa. We illustrate this by considering what happens to three collinearities in the Euclidean plane when an affine transformation takes the symmedian point into the incentre. C' 9 pt circle C'' A B'' Anticompleme ntary triangle F B' W' W E' L M V O X Z E F' K 4 V' K'' Y G T H N' D B U D'U' C Triplicate ratio Circle A'' A' Fig.1 Three collinearities amongst triangle centres in the Euclidean plane 1 1. When the circumconic, the nine-point conic, the triplicate ratio conic and the 7 pt. conic are all circles The condition for this is that the circumconic is a circle and then the tangents at A, B, C form a triangle A'B'C' consisting of the ex-symmedian points A'(– a2, b2, c2) and similarly for B', C' by appropriate change of sign and when this happen AA', BB', CC' are concurrent at the symmedian point K(a2, b2, c2). There are two very well-known collinearities and one less well-known, and we now describe them. First there is the Euler line containing amongst others the circumcentre O with x-co-ordinate a2(b2 + c2 – a2), the centroid G(1, 1, 1), the orthocentre H with x-co-ordinate 1/(b2 + c2 – a2) and T, the nine-point centre which is the midpoint of OH. -

![Arxiv:2101.02592V1 [Math.HO] 6 Jan 2021 in His Seminal Paper [10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7323/arxiv-2101-02592v1-math-ho-6-jan-2021-in-his-seminal-paper-10-957323.webp)

Arxiv:2101.02592V1 [Math.HO] 6 Jan 2021 in His Seminal Paper [10]

International Journal of Computer Discovered Mathematics (IJCDM) ISSN 2367-7775 ©IJCDM Volume 5, 2020, pp. 13{41 Received 6 August 2020. Published on-line 30 September 2020 web: http://www.journal-1.eu/ ©The Author(s) This article is published with open access1. Arrangement of Central Points on the Faces of a Tetrahedron Stanley Rabinowitz 545 Elm St Unit 1, Milford, New Hampshire 03055, USA e-mail: [email protected] web: http://www.StanleyRabinowitz.com/ Abstract. We systematically investigate properties of various triangle centers (such as orthocenter or incenter) located on the four faces of a tetrahedron. For each of six types of tetrahedra, we examine over 100 centers located on the four faces of the tetrahedron. Using a computer, we determine when any of 16 con- ditions occur (such as the four centers being coplanar). A typical result is: The lines from each vertex of a circumscriptible tetrahedron to the Gergonne points of the opposite face are concurrent. Keywords. triangle centers, tetrahedra, computer-discovered mathematics, Eu- clidean geometry. Mathematics Subject Classification (2020). 51M04, 51-08. 1. Introduction Over the centuries, many notable points have been found that are associated with an arbitrary triangle. Familiar examples include: the centroid, the circumcenter, the incenter, and the orthocenter. Of particular interest are those points that Clark Kimberling classifies as \triangle centers". He notes over 100 such points arXiv:2101.02592v1 [math.HO] 6 Jan 2021 in his seminal paper [10]. Given an arbitrary tetrahedron and a choice of triangle center (for example, the circumcenter), we may locate this triangle center in each face of the tetrahedron. -

The Uses of Homogeneous Barycentric Coordinates in Plane Euclidean Geometry by PAUL

The uses of homogeneous barycentric coordinates in plane euclidean geometry by PAUL YIU Department of Mathematical Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA The notion of homogeneous barycentric coordinates provides a pow- erful tool of analysing problems in plane geometry. In this paper, we explain the advantages over the traditional use of trilinear coordinates, and illustrate its powerfulness in leading to discoveries of new and in- teresting collinearity relations of points associated with a triangle. 1. Introduction In studying geometric properties of the triangle by algebraic methods, it has been customary to make use of trilinear coordinates. See, for examples, [3, 6, 7, 8, 9]. With respect to a ¯xed triangle ABC (of side lengths a, b, c, and opposite angles ®, ¯, °), the trilinear coordinates of a point is a triple of numbers proportional to the signed distances of the point to the sides of the triangle. The late Jesuit mathematician Maurice Wong has given [9] a synthetic construction of the point with trilinear coordinates cot ® : cot ¯ : cot °, and more generally, in [8] points with trilinear coordinates a2nx : b2ny : c2nz from one with trilinear coordinates x : y : z with respect to a triangle with sides a, b, c. On a much grandiose scale, Kimberling [6, 7] has given extensive lists of centres associated with a triangle, in terms of trilinear coordinates, along with some collinearity relations. The present paper advocates the use of homogeneous barycentric coor- dinates instead. The notion of barycentric coordinates goes back to MÄobius. See, for example, [4]. With respect to a ¯xed triangle ABC, we write, for every point P on the plane containing the triangle, 1 P = (( P BC)A + ( P CA)B + ( P AB)C); ABC 4 4 4 4 and refer to this as the barycentric coordinate of P . -

Degree of Triangle Centers and a Generalization of the Euler Line

Beitr¨agezur Algebra und Geometrie Contributions to Algebra and Geometry Volume 51 (2010), No. 1, 63-89. Degree of Triangle Centers and a Generalization of the Euler Line Yoshio Agaoka Department of Mathematics, Graduate School of Science Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima 739–8521, Japan e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We introduce a concept “degree of triangle centers”, and give a formula expressing the degree of triangle centers on generalized Euler lines. This generalizes the well known 2 : 1 point configuration on the Euler line. We also introduce a natural family of triangle centers based on the Ceva conjugate and the isotomic conjugate. This family contains many famous triangle centers, and we conjecture that the de- gree of triangle centers in this family always takes the form (−2)k for some k ∈ Z. MSC 2000: 51M05 (primary), 51A20 (secondary) Keywords: triangle center, degree of triangle center, Euler line, Nagel line, Ceva conjugate, isotomic conjugate Introduction In this paper we present a new method to study triangle centers in a systematic way. Concerning triangle centers, there already exist tremendous amount of stud- ies and data, among others Kimberling’s excellent book and homepage [32], [36], and also various related problems from elementary geometry are discussed in the surveys and books [4], [7], [9], [12], [23], [26], [41], [50], [51], [52]. In this paper we introduce a concept “degree of triangle centers”, and by using it, we clarify the mutual relation of centers on generalized Euler lines (Proposition 1, Theorem 2). Here the term “generalized Euler line” means a line connecting the centroid G and a given triangle center P , and on this line an infinite number of centers lie in a fixed order, which are successively constructed from the initial center P 0138-4821/93 $ 2.50 c 2010 Heldermann Verlag 64 Y. -

Chapter 10 Isotomic and Isogonal Conjugates

Chapter 10 Isotomic and isogonal conjugates 10.1 Isotomic conjugates The Gergonne and Nagel points are examples of isotomic conjugates. Two points P and Q (not on any of the side lines of the reference triangle) are said to be isotomic conjugates if their respective traces are symmetric with respect to the midpoints of the corresponding sides. Thus, BX = X′C, CY = Y ′A, AZ = Z′B. B X′ Z X Z′ P P • C A Y Y ′ We shall denote the isotomic conjugate of P by P •. If P =(x : y : z), then 1 1 1 P • = : : =(yz : zx : xy). x y z 320 Isotomic and isogonal conjugates 10.1.1 The Gergonne and Nagel points 1 1 1 Ge = s a : s b : s c , Na =(s a : s : s c). − − − − − − Ib A Ic Z′ Y Y Z I ′ Na Ge B C X X′ Ia 10.1 Isotomic conjugates 321 10.1.2 The isotomic conjugate of the orthocenter The isotomic conjugate of the orthocenter is the point 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 H• =(b + c a : c + a b : a + b c ). − − − Its traces are the pedals of the deLongchamps point Lo, the reflection of H in O. A Z′ L Y o O Y ′ H• Z H B C X X′ Exercise 1. Let XYZ be the cevian triangle of H•. Show that the lines joining X, Y , Z to the midpoints of the corresponding altitudes are concurrent. What is the common point? 1 2. Show that H• is the perspector of the triangle of reflections of the centroid G in the sidelines of the medial triangle. -

The Ballet of Triangle Centers on the Elliptic Billiard

Journal for Geometry and Graphics Volume 24 (2020), No. 1, 79–101. The Ballet of Triangle Centers on the Elliptic Billiard Dan S. Reznik1, Ronaldo Garcia2, Jair Koiller3 1Data Science Consulting Rio de Janeiro RJ 22210-080, Brazil email: [email protected] 2Instituto de Matemática e Estatística, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia GO, Brazil email: [email protected] 3Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora MG, Brazil email: [email protected] Abstract. We explore a bevy of new phenomena displayed by 3-periodics in the Elliptic Billiard, including (i) their dynamic geometry and (ii) the non-monotonic motion of certain Triangle Centers constrained to the Billiard boundary. Fasci- nating is the joint motion of certain pairs of centers, whose many stops-and-gos are akin to a Ballet. Key Words: elliptic billiard, periodic trajectories, triangle center, loci, dynamic geometry. MSC 2010: 51N20, 51M04, 51-04, 37-04 1. Introduction We investigate properties of the 1d family of 3-periodics in the Elliptic Billiard (EB). Being uniquely integrable [13], this object is the avis rara of planar Billiards. As a special case of Poncelet’s Porism [4], it is associated with a 1d family of N-periodics tangent to a con- focal Caustic and of constant perimeter [27]. Its plethora of mystifying properties has been extensively studied, see [26, 10] for recent treatments. Initially we explored the loci of Triangle Centers (TCs): e.g., the Incenter X1, Barycenter X2, Circumcenter X3, etc., see summary below. The Xi notation is after Kimberling’s Encyclopedia [14], where thousands of TCs are catalogued. -

Volume 3 2003

FORUM GEOMETRICORUM A Journal on Classical Euclidean Geometry and Related Areas published by Department of Mathematical Sciences Florida Atlantic University b bbb FORUM GEOM Volume 3 2003 http://forumgeom.fau.edu ISSN 1534-1178 Editorial Board Advisors: John H. Conway Princeton, New Jersey, USA Julio Gonzalez Cabillon Montevideo, Uruguay Richard Guy Calgary, Alberta, Canada George Kapetis Thessaloniki, Greece Clark Kimberling Evansville, Indiana, USA Kee Yuen Lam Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Tsit Yuen Lam Berkeley, California, USA Fred Richman Boca Raton, Florida, USA Editor-in-chief: Paul Yiu Boca Raton, Florida, USA Editors: Clayton Dodge Orono, Maine, USA Roland Eddy St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada Jean-Pierre Ehrmann Paris, France Lawrence Evans La Grange, Illinois, USA Chris Fisher Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Rudolf Fritsch Munich, Germany Bernard Gibert St Etiene, France Antreas P. Hatzipolakis Athens, Greece Michael Lambrou Crete, Greece Floor van Lamoen Goes, Netherlands Fred Pui Fai Leung Singapore, Singapore Daniel B. Shapiro Columbus, Ohio, USA Steve Sigur Atlanta, Georgia, USA Man Keung Siu Hong Kong, China Peter Woo La Mirada, California, USA Technical Editors: Yuandan Lin Boca Raton, Florida, USA Aaron Meyerowitz Boca Raton, Florida, USA Xiao-Dong Zhang Boca Raton, Florida, USA Consultants: Frederick Hoffman Boca Raton, Floirda, USA Stephen Locke Boca Raton, Florida, USA Heinrich Niederhausen Boca Raton, Florida, USA Table of Contents Bernard Gibert, Orthocorrespondence and orthopivotal cubics,1 Alexei Myakishev, -

Triangle Centers Defined by Quadratic Polynomials

Math. J. Okayama Univ. 53 (2011), 185–216 TRIANGLE CENTERS DEFINED BY QUADRATIC POLYNOMIALS Yoshio Agaoka Abstract. We consider a family of triangle centers whose barycentric coordinates are given by quadratic polynomials, and determine the lines that contain an infinite number of such triangle centers. We show that for a given quadratic triangle center, there exist in general four principal lines through this center. These four principal lines possess an intimate connection with the Nagel line. Introduction In our previous paper [1] we introduced a family of triangle centers PC based on two conjugates: the Ceva conjugate and the isotomic conjugate. PC is a natural family of triangle centers, whose barycentric coordinates are given by polynomials of edge lengths a, b, c. Surprisingly, in spite of its simple construction, PC contains many famous centers such as the centroid, the incenter, the circumcenter, the orthocenter, the nine-point center, the Lemoine point, the Gergonne point, the Nagel point, etc. By plotting the points of PC, we know that they are not independently distributed in R2, or rather, they possess a strong mutual relationship such as 2 : 1 point configuration on the Euler line (see Figures 2, 4). In [1] we generalized this 2 : 1 configuration to the form “generalized Euler lines”, which contain an infinite number of centers in PC . Furthermore, the centers in PC seem to have some additional structures, and there frequently appear special lines that contain an infinite number of centers in PC. In this paper we call such lines “principal lines” of PC. The most famous principal lines are the Euler line mentioned above, and the Nagel line, which passes through the centroid, the incenter, the Nagel point, the Spieker center, etc. -

1. Math Olympiad Dark Arts

Preface In A Mathematical Olympiad Primer , Geoff Smith described the technique of inversion as a ‘dark art’. It is difficult to define precisely what is meant by this phrase, although a suitable definition is ‘an advanced technique, which can offer considerable advantage in solving certain problems’. These ideas are not usually taught in schools, mainstream olympiad textbooks or even IMO training camps. One case example is projective geometry, which does not feature in great detail in either Plane Euclidean Geometry or Crossing the Bridge , two of the most comprehensive and respected British olympiad geometry books. In this volume, I have attempted to amass an arsenal of the more obscure and interesting techniques for problem solving, together with a plethora of problems (from various sources, including many of the extant mathematical olympiads) for you to practice these techniques in conjunction with your own problem-solving abilities. Indeed, the majority of theorems are left as exercises to the reader, with solutions included at the end of each chapter. Each problem should take between 1 and 90 minutes, depending on the difficulty. The book is not exclusively aimed at contestants in mathematical olympiads; it is hoped that anyone sufficiently interested would find this an enjoyable and informative read. All areas of mathematics are interconnected, so some chapters build on ideas explored in earlier chapters. However, in order to make this book intelligible, it was necessary to order them in such a way that no knowledge is required of ideas explored in later chapters! Hence, there is what is known as a partial order imposed on the book.