From Tolar to Euro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007

4 THE CASH CHANGEOVER IN CYPRUS AND MALTA Six years after the successful introduction of the Monnaie de Paris minted 200.0 million euro coins euro banknotes and coins in 12 euro area countries with a face value of €56.1 million for Malta. at the same time and one year after Slovenia joined the Eurosystem, the euro banknotes and The Central Bank of Cyprus began frontloading coins were successfully introduced in Cyprus and euro coins to credit institutions on 22 October 2007; Malta on 1 January 2008. After a dual circulation the frontloading of euro banknotes began on period of one month, the euro had fully replaced 19 November 2007. Sub-frontloading to retailers the Cyprus pound and the Maltese lira. and the cash-operated machine industry started at the same time as the frontloading operation. As in the previous cash changeovers, timely and A widespread predistribution of euro coins was comprehensive preparation was crucial to the supported by making some 40,000 pre-packed smooth introduction of the euro banknotes and coin starter kits, worth €172 each, available to coins. Both Cyprus and Malta had established businesses and retailers from 3 December 2007. changeover plans at the national level long 250,000 mini-kits, worth CYP 10 each, went on before €-Day. These plans were based on, among sale to the general public on the same date. other things, the legal framework adopted by the Governing Council in July 2006 in relation to In Malta the frontloading of euro coins started certain preparations for the euro cash changeover in late September 2007, while the frontloading and the frontloading and sub-frontloading of euro of euro banknotes began in late October. -

Small Economies in the Euro Area

CONTENTS EDITORIAL Mitja Gaspari: Jumping the Last Hurdle Towards the Final Stage of Convergence 1 MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK OF SMALL OPEN ECONOMY Willem H. Buiter and Anne C. Sibert: When Should the New Central European Members Join the Eurozone? 5 George Kopits: Policy Scenarios for Adopting the Euro 12 Dejan Krušec: Common Monetary Policy and Small Open Economies 17 Lars Calmfors: The Revised Stability and Growth Pact – A Critical Assessment 22 Fabio Mucci and Debora Revoltella: Banking Systems in the New EU Members and Acceding Countries 27 Mathilde Maurel: The Political Business Cycles in the EU Enlarged 38 FINANCIAL MARKETS AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN EMU Kevin R. James: Small Countries, Big Markets: Achieving Financial Stability in Small Sophisticated Economies 43 Garry J. Schinasi and Pedro Gustavo Teixeira: Financial Crisis Management in the European Single Financial Market 47 Franjo Štiblar: Consolidations and Diversifications in Financial Sector 56 Fabrizio Coricelli: Financial Deepening and Financial Integration of New EU Countries 70 THE CASE OF SLOVENIA Ivan Ribnikar: Slovenian »Transition« and Monetary Policy 75 Igor Masten: Expected Stabilization Effects of Euro Adoption on Slovenian Economy 83 Velimir Bole: Fiscal Policy in Slovenia after Entering Euro – New Goals and Soundness? 87 Božo Jašovič and Borut Repanšek: Application of the Balance Sheet Approach to Slovenia 95 STATISTICAL APPENDIX Matjaž Noč: Selected Macroeconomic and Financial Indicators 105 EDITORIAL Jumping the Last Hurdle Towards the Final Stage of Convergence Mitja Gaspari * n 1 January 2007, Slovenia will join the 12 current members of the euro area and adopt the single European currency. This is a historic moment for Slovenia and for euro area enlargement. -

European Union

EUROPEAN UNION Brussels, 27 June 2004 COMMUNIQUE At the request of the Slovenian authorities, the ministers of the euro area Member States of the European Union, the President of the European Central Bank and the ministers and the central bank governors of Denmark and Slovenia have decided, by mutual agreement, following a common procedure involving the European Commission and after consultation of the Economic and Financial Committee, to include the Slovenian tolar in the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II). The central rate of the Slovenian tolar is set at 1 euro = 239.640 tolar. The standard fluctuation band of plus or minus 15 percent will be observed around the central rate of the tolar. The agreement on participation of the tolar in ERM II is based on a firm commitment by the Slovenian authorities to continue to take the necessary measures to lower inflation in a sustainable way: these include most notably measures aimed at further liberalising administered prices and advancing further with de-indexation, in particular of the wage and certain social transfer setting mechanisms. Continued vigilance will be needed so that domestic cost developments, in particular wages, are in line with productivity growth. The authorities, together with the responsible EU bodies, will closely monitor macroeconomic developments. Fiscal policy will have to play a central role in controlling demand-induced inflationary pressures and financial supervision will assist in containing domestic credit growth. Structural reforms aimed at further enhancing the economy’s flexibility and adaptability will be implemented in a timely fashion so as to strengthen domestic adjustment mechanisms and to maintain the overall competitiveness of the economy. -

Name, Surname

Flash Eurobarometer 412 LITHUANIA AFTER THE EURO CHANGEOVER REPORT Fieldwork: January 2015 Publication: January 2015 This survey has been requested by the European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs and co-ordinated by the Directorate-General for Communication. This document does not represent the point of view of the European Commission. The interpretations and opinions contained in it are solely those of the authors. Flash Eurobarometer 412 - TNS Political & Social Flash EB 412 survey among the general public AFTER Project title euro changeover in Lithuania – January 2015 Linguistic Version EN Catalogue Number KC-01-15-047-EN-N ISBN 978-92-79-45359-5 DOI 10.2765/396675 © European Union, 2015 Flash Eurobarometer 412 Lithuania after the euro changeover Conducted by TNS Political & Social at the request of the European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Survey co-ordinated by the European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication (DG COMM "Strategy, Corporate Communication Actions and Eurobarometer" Unit) FLASH EUROBAROMETER 412 “Lithuania after the euro changeover” TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 3 MAIN FINDINGS ................................................................................................. 5 I. SUPPORT FOR THE EURO ............................................................................ 8 1.1 General perceptions of the euro ............................................................... -

Central Bank Sterilization Policy: the Experiences of Slovenia and Lessons for Countries in Southeastern Europe1

√ Workshops Proceedings of OeNB Workshops Any Lessons for Southeastern Europe? Lessons for Any Emerging Markets: Any Lessons for Southeastern Europe? Emerging Markets: Emerging March 5 and 6, 2007 12 No. Workshops N0. N0. Workshops 12 Stability and Security. Central Bank Sterilization Policy: The Experiences of Slovenia and Lessons for 1 Countries in Southeastern Europe Darko Bohnec Banka Slovenije Marko Košak University of Ljubljana 1. Introduction It is well known that countries in the Southeastern European (SEE) region have experienced a substantial and gradually intensified inflow of foreign capital during the entire period of economic transition (Markievicz, 2006). Central banks in those countries had to adapt their monetary policy operations and exchange rate regimes to the changing conditions. Especially in those countries that responded by implementing a managed floating exchange rate regime, central banks had to find viable solutions in order to support the “consistency triangle” policy framework (Bofinger and Wollmershaeuser, 2001). Advocates of the “consistency triangle” policy framework claim that simultaneous determination of the optimum interest rate level and the optimum exchange rate path is possible. Effective sterilization procedures need to be activated by the central bank in order for the policy framework to be operational. The experiences of some developing countries in the 1990s confirm the viability of sterilization as a key element of the central bank’s monetary policy in circumstances of intensified inflow of foreign capital (Lee, 1996). However, certain limitations to this kind of strategy exist, which in most cases central banks need to address properly by developing alternative procedures and instruments instead of classical open-market operations. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

European Economy. Convergence Report 2004

European Economy Convergence Report 2004 – Technical annex A Commission services working paper SEC(2004)1268 PROVISIONAL LAYOUT The definitive version will be published as European Economy No 6/2004 http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/convergencereports2004_en.htm Acknowledgements This paper was prepared in the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs under the supervision of Klaus Regling, Director-General, and Antonio J. Cabral, Deputy Director-General. The main contributors to the paper were Johan Baras, Sean Berrigan, Carsten Brzeski, Adriaan Dierx, Christine Gerstberger, Alexandr Hobza, Fabienne Ilzkovitz, Filip Keereman, Paul Kutos, Baudouin Lamine, João Nogueira Martins, Moises Orellana Pena, Lucio R. Pench, Jiri Plecity, Stéphanie Riso, Delphine Sallard, Charlotte Van Hooydonk, Johan Verhaeven and Joachim Wadefjord. Country-specific contributions were provided by Georg Busch, Juan Ramon Calaf Sole, Nathalie Darnaut, Per Eckefeldt, Luis Fau Sebastian, Barbara Kauffmann, Filip Keereman, Viktoria Kovacs, Carlos Martinez Mongay, Marek Mora, Willem Noë, Mateja Peternelj, José Luis Robledo Fraga, Agnieszka Skuratowicz, Siegfried Steinlein, Kristine Vlagsma, Helga Vogelmann and Ralph Wilkinson. Charlotte Van Hooydonk edited the paper. Statistical and technical assistance was provided by Vittorio Gargaro, Tony Tallon and André Verbanck. Contents 1. Introduction and overview.................................................................................................................1 -

Exchange Rate of the Slovenian Tolar in the Context of Slovenia's Inclusion in the Eu and in the Emu

EXCHANGE RATE OF THE SLOVENIAN TOLAR IN THE CONTEXT OF SLOVENIA'S INCLUSION IN THE EU AND IN THE EMU 9ODGLPLU /DYUDþ WORKING PAPER No. 1, 1999 EXCHANGE RATE OF THE SLOVENIAN TOLAR IN THE CONTEXT OF SLOVENIA'S INCLUSION IN THE EU AND IN THE EMU 9ODGLPLU /DYUDþ WORKING PAPER No. 1, 1999 E-mail address of the author: [email protected] Editor of the WP series: Peter Stanovnik © 1999 Inštitut za ekonomska raziskovanja This paper is also available on Internet home page: http//www.ier.si Ljubljana, January 1999 2 Introduction Creation of the European economic and monetary union (EMU) and successive introduction of the European single currency, the euro, is a historic event, which will lead to fundamental changes in the EU economies. These changes will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the economies of the Central European transition countries, candidates for a full membership in the EU, similarly as the preparations of the EU countries for the EMU and their efforts to meet the Maastricht convergence criteria have already affected the Central European economies. Policy-makers and other decision-makers at various levels (enterprises, banks, government bodies) will have to adapt to the changing environment, first by adjusting to the irrevocably fixed exchange rates among the EU currencies participating in the EMU and then by adjusting to the introduction of the euro and to the elimination of national currencies in the euro zone. This paper, however, does not concentrate on these otherwise important issues of the impact of the EMU on the Central European countries. It focuses primarily on the most direct questions related to the EMU for these countries - why, how and when Slovenia and the other Central European EU candidate countries will be ready to join the EMU. -

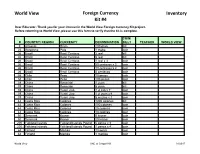

World View Foreign Currency Kit #4 Inventory

World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 Dear Educator: Thank you for your interest in the World View Foreign Currency Kit project. Before returning to World View, please use this form to verify that the kit is complete. COIN/ # COUNTRY/ REGION CURRENCY DENOMINATION BILL? TEACHER WORLD VIEW 9 Armenia Dram 200 dram bill 25 Botswana Pula 1 thebe coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 2 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 1 real x 3 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 50 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 10 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 centavos coin 38 Chile Peso 10 pesos coin 38 Chile Peso 100 pesos coin 39 China Renminbi 1 yuan bill 39 China Renminbi 5 yuan bill 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi jiao x 7 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi yuan x 6 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 5 wu jiao x 2 coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 1000 colones bill 44 Costa Rica Colones 100 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 25 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 10 colones coin 50 Denmark Kroner 5 kroner coin 50 Denmark Kroner 20 kroner coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 5 pence x 3 coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 1 pence x 4 coin 64 Finland Markka 10 penni coin 64 Finland Markka 1 markka coin World View UNC at Chapel Hill 01/2017 World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 69 Germany Deutsche Mark 10 Deutsche mark bill 80 Hungary Forint 20 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 100 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 5 forint coin 92 Japan Yen 1 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen 10 yen coin 92 Japan Yen 100 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen -

Economic Policies on Slovenia's Road to the Euro Area

Economic Systems 32 (2008) 92–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/ecosys Economic policies on Slovenia’s road to the euro area Klaus Weyerstrass * Institute for Advanced Studies (IHS), Stumpergasse 56, A-1060 Vienna, Austria Received 27 November 2006; received in revised form 15 July 2007; accepted 3 September 2007 Abstract On 1 January 2007, Slovenia was the first new EU member state to enter the euro area. Since June 2004, the Slovenian tolar participated in the exchange rate mechanism ERM-II with a central parity of 239.64 against the euro. This parity was also the conversion rate upon euro area accession. Applying a macroeconometric model of Slovenia, this paper analyses the macroeconomic effects of different con- version rates. These simulations are compared to a scenario with flexible exchange rates. The best results are obtained with the actual conversion rate. In addition, it is shown that the labour market performance can be significantly improved by cutting non-wage labour costs. # 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. JEL classification: C53; E17; F15 Keywords: Slovenia; Euro area; Fiscal policy; Macroeconometric model 1. Introduction On 1 January 2007, the euro area was enlarged for the first time since the euro cash changeover in 2002. In addition, Slovenia was the first of the eight countries from Central and Eastern Europe that had joined the European Union in May 2004 (together with Cyprus and Malta) to adopt the common currency. Becoming a part of the euro area further enhances the European economic integration of Slovenia. From the first day of membership onwards, the new member countries have been participating in the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). -

Commentary/Grech

√ Oesterreichische Nationalbank Eurosystem Workshops Proceedings of OeNB Workshops Macroeconomic Models and Forecasts for Austria November 11 to 12, 2004 No. 5 COMMENTARY Comment on “Evaluating Euro Exchange Rate Predictions from a Battery of Multivariate Models” Harald Grech Oesterreichische Nationalbank Forecasting exchange rates – in particular – in the short run is a controversial issue, far from being settled. Various empirical exchange rate models which are dealt with in a huge number of empirical papers are not found to consistently outperform the random walk. So, although researchers occasionally claim that their model can beat the random walk, the scientific consensus today is that the results of the classical paper of Meese and Rogoff (1983) still stand. Another noteworthy conclusion from the empirical literature is that since the breakdown of Bretton Woods, exchange rates in general have become a lot more volatile. There is however no evidence that the fundamentals which are – according to the theoretical models – deemed to determine the value of the exchange rates have become more volatile during the same period. This is clearly the opposite to the predictions of the various models, indicating that exchange rate variability can only increase if the underlying fundamental volatility has also increased. Obviously, exchange rate volatility is – at least to a great extent – separated from the variability of the fundamentals, see for instance de Grauwe (2000). Obstfeld and Rogoff (2000) refer to this perception as one of the six major puzzles in international finance. The economic theory behind the exchange rate forecasting exercise of the Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna, is the monetary model of exchange rate determination (MM-model). -

Flash Eurobarometer 309 January 2011

GESIS Study ID ..................................................... ZA5463 Flash Eurobarometer 309 January 2011 Estonia Euro Introduction, Ex-Post Citizen Survey Basic questionnaire The GALLUP Organization FLASH 309 D1. How old are you? - ............................................................................................................ - [DK/NA] .............................................................................................. 99 D2. Where do you live? - In an urban area ................................................................................... 1 - In the rest of the country ..................................................................... 2 - [DK/NA] ................................................................................................ 9 D3. Regarding your current occupation, are you... - Self-employed ...................................................................................... 1 - Employee/non-manual worker ............................................................ 2 - Employee/manual worker ................................................................... 3 - Without a professional activity (looking after the home, student, seeking a job, retired etc) ................................................... 4 - [DK/NA] ................................................................................................ 9 D4. RECORD RESPONDENT’S SEX - Male ..................................................................................................... 1 - Female .................................................................................................