The Changing Faces of Populism Systemic Challengers in Europe and the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti Choice Extremists Defeated in Ireland but New Abortion Legislation Is Worthless - Infoshop News

7/23/13 Anti choice extremists defeated in Ireland but new abortion legislation is worthless - Infoshop News Contribute Advanced Search Site Statistics Directory aboutus editorial getpublished moderation Polls Calendar "Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth." Welcome to Infoshop News Tuesday, July 23 2013 @ 11:22 AM CDT advanced search Search Main Menu Anti choice extremists defeated in Ireland but new abortion legislation is Infoshop Home worthless Infoshop News Home Contact Us Thursday, July 18 2013 @ 01:13 AM CDT Contributed by: Admin Views: 593 Occupy Sandy Despite spending in the region of a million euro and getting the backing of the catholic church its now clear that the antichoice extremists of Youth Defence & the Pro Life Campaign were resoundingly defeated when the Dail finally voted though legislation implementing the XCase judgment of 21 years ago. This time last year they were confident that they already had enough Fine Gael TD's on board to block the required legislation but they reckoned against the wave of public anger that followed the death of Savita Halappanavar after she was denied a potentially life saving abortion in a Galway hospital. Anti choice extremists defeated in Ireland but new abortion legislation is worthless by AndrewNFlood Anarchist Writers July 15, 2013 Despite spending in the region of a million euro and getting the backing of the catholic church its now clear that the antichoice extremists of Youth Defence & the Pro Life Campaign were resoundingly defeated when the Dail finally voted though legislation implementing the XCase judgment of 21 years ago. -

The English Defence League: Challenging Our Country and Our Values of Social Inclusion, Fairness and Equality

THE ENGLISH DEFENCE LEAGUE: CHALLENGING OUR COUNTRY AND OUR VALUES OF SOCIAL INCLUSION, FAIRNESS AND EQUALITY by Professor Nigel Copsey Professor of Modern History School of Arts and Media Teesside University (UK) On Behalf of Faith Matters 2 Foreword This report focuses on the English Defence League (EDL) and asks whether the organisation poses a threat to our country and our values of social inclusion, fairness and equality. This report demonstrates clearly that the English Defence League does not represent the values which underpin our communities and our country: respect for our fellow citizens, respect for difference, and ensuring the safety and peace of communities and local areas. On the contrary, actions by the EDL have led to fear within communities and a sense that they are ‘under siege’ and under the media and national ‘spotlight’. Many within these communities feel that the peace and tranquillity which they deserve has been broken up by the EDL, whose main aim is to increase tension, raise hate and increase community division by the use of intimidating tactics. These are not the actions of a group ‘working against extremism’. These are the actions of extremists in their own right, masquerading as a grass roots social force, supposedly bringing their brand of community resilience against ‘Muslim extremism’. It is essential to inoculate communities against the toxins that are being injected into these areas by the EDL and other extremist groups like Al-Muhajiroun. Letting these groups go unchecked destroys what we stand for and damages our image globally. This report has been put together in partnership with Professor Nigel Copsey and we hope that it activates social action against those who seek to divide our communities. -

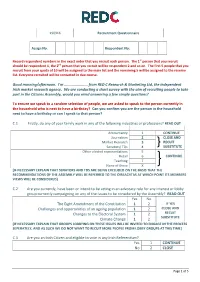

RED C Recruitment Questionnaire

190916 Recruitment Questionnaire Assign No. Respondent No: Record respondent numbers in the exact order that you recruit each person. The 1st person that you recruit should be respondent 1, the 2nd person that you recruit will be respondent 2 and so on. The first 5 people that you recruit from your quota of 10 will be assigned to the main list and the remaining 5 will be assigned to the reserve list. Everyone recruited will be contacted in due course. Good morning/afternoon. I'm ...................... from RED C Research & Marketing Ltd, the independent Irish market research agency. We are conducting a short survey with the aim of recruiting people to take part in the Citizens Assembly, would you mind answering a few simple questions? To ensure we speak to a random selection of people, we are asked to speak to the person currently in the household who is next to have a birthday? Can you confirm you are the person in the household next to have a birthday or can I speak to that person? C.1 Firstly, do any of your family work in any of the following industries or professions? READ OUT Accountancy 1 CONTINUE Journalism 2 CLOSE AND Market Research 3 RECUIT Senators/ TDs 4 SUBSTITUTE Other elected representatives 5 Retail 6 CONTINUE Teaching 7 None of these X [IF NECESSARY EXPLAIN THAT SENATORS AND TDS ARE BEING EXCLUDED ON THE BASIS THAT THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ASSEMBLY WILL BE REFERRED TO THE OIREACHTAS AT WHICH POINT ITS MEMBERS VIEWS WILL BE CONSIDERED] C.2 Are you currently, have been or intend to be acting in an advocacy role for any -

On Strategy: a Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney

Cover design by Dale E. Cordes, Army University Press On Strategy: A Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney Combat Studies Institute Press Fort Leavenworth, Kansas An imprint of The Army University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Finney, Nathan K., editor. | U.S. Army Combined Arms Cen- ter, issuing body. Title: On strategy : a primer / edited by Nathan K. Finney. Other titles: On strategy (U.S. Army Combined Arms Center) Description: Fort Leavenworth, Kansas : Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Arms Center, 2020. | “An imprint of The Army University Press.” | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020020512 (print) | LCCN 2020020513 (ebook) | ISBN 9781940804811 (paperback) | ISBN 9781940804811 (Adobe PDF) Subjects: LCSH: Strategy. | Strategy--History. Classification: LCC U162 .O5 2020 (print) | LCC U162 (ebook) | DDC 355.02--dc23 | SUDOC D 110.2:ST 8. LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020512. LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020513. 2020 Combat Studies Institute Press publications cover a wide variety of military topics. The views ex- pressed in this CSI Press publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Depart- ment of the Army or the Department of Defense. A full list of digital CSI Press publications is available at https://www.armyu- press.army.mil/Books/combat-studies-institute. The seal of the Combat Studies Institute authenticates this document as an of- ficial publication of the CSI Press. It is prohibited to use the CSI’s official seal on any republication without the express written permission of the director. Editors Diane R. -

The Impact of Youth Work in Europe: a Study of Five European Countries

The Impact of Youth Work in Europe: A Study of Five European Countries Edited by Jon Ord with Marc Carletti, Susan Cooper, Christophe Dansac, Daniele Morciano, Lasse Siurala and Marti Taru The Impact of Youth Work in Europe: A Study of Five European Countries ISBN 978-952-456-301-7 (printed) ISBN 978-952-456-302-4 (online) ISSN 2343-0664 (printed) ISSN 2343-0672 (online) Humak University of Applied Sciences Publications, 56. © 2018 Authors Jon Ord with Marc Carletti, Susan Cooper, Christophe Dansac, Daniele Morciano, Lasse Siurala and Marti Taru Layout Emilia Reponen Cover Clayton Thomas Printing house Juvenes Print - Suomen yliopistopaino Oy Printing place Helsinki Dedicated to all the young people who shared their stories Contents Acknowledgements ............................................. 10 Notes on Contributors ......................................... 11 Jon Ord Introduction ......................................................... 13 Section One: The Context of Youth Work Manfred Zentner and Jon Ord Chapter 1: European Youth Work Policy Context ...17 Jon Ord and Bernard Davies Chapter 2: Youth Work in the UK (England) .......... 32 Lasse Siurala Chapter 3: Youth Work in Finland ........................ 49 Marti Taru Chapter 4: Youth Work in Estonia ........................ 63 Daniele Morciano Chapter 5: Youth Work in Italy ............................. 74 Marc Carletti and Christophe Dansac Chapter 6: Youth Work in France ......................... 86 Susan Cooper Chapter 7: Methodology of Transformative Evaluation .................................... 100 Section Two: The Impact of Youth Work Jon Ord Background to the Research and Analysis of Findings ...................................... 112 Susan Cooper Chapter 8: Impact of Youth Work in the UK (England) .............................................. 116 Lasse Siurala and Eeva Sinisalo-Juha Chapter 9: Impact of Youth Work in Finland ......... 138 Marti Taru and Kaur Kötsi Chapter 10: Impact of Youth Work in Estonia ...... -

SAN MARINO This File Contains Election Results for the Sammarinese Grand and General Council for 1998, 2001, 2006, 2008, 2012

SAN MARINO This file contains election results for the Sammarinese Grand and General Council for 1998, 2001, 2006, 2008, 2012, and 2016. This file has a format different from many others in Election Passport. Note: Major changes to the electoral system occurred in 2008 with parties newly able to maintain separate ballot lines while running in coalitions eligible for a majority bonus and a runoff between the top two coalitions if none achieves a first-round majority. RG Region The following eight regions are used in the dataset. Africa Asia Western Europe Eastern Europe Latin America North America Caribbean Oceania CTR_N Country Name CTR Country Code Country codes developed by the UN (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/) 674 San Marino YR Election Year MN Election Month 1 January 2 February 3 March 4 April 5 May 6 June 7 July 8 August 9 September 10 October 11 November 12 December CST_N Constituency Name San Marino is a single electoral constituency. Recorded here are the names of San Marino’s nine municipalities, the three abroad constituencies, and the name of the country for rows reporting results for all of San Marino. CST Constituency Code A unique numeric code assigned to each of the units recorded in CST_N: Municipalities (ISO Codes) 1 Acquaviva 2 Borgo Maggiore 3 Chiesanuova 4 Domagnano 5 Faetano 6 Fiorentino 7 Montegiardino 8 San Marino Città 9 Serraville Abroad Constituency 106 Estero (Abroad) Borgo Maggiore 108 Estero (Abroad) Città 109 Estero (Abroad) Serraville Country Totals 674 San Marino MAG District Magnitude San Marino is a single constituency with seats allocated within the country as a whole. -

The Extreme Right Wing in Bulgaria

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS The Extreme Right Wing in Bulgaria ANTONIY TODOROV January 2013 n The extreme right wing (also known as the far right) consists of parties and organi- sations ideologically linked by their espousal of extreme forms of cultural conserva- tism, xenophobia and, not infrequently, racism. They are strong advocates of order imposed by a »strong hand« and they profess a specific form of populism based on opposition between the elite and the people. n The most visible extreme right organisation in Bulgaria today is the Attack Party, which has been in existence since 2005. Since its emergence, voter support for the Attack Party has significantly grown and in 2006 its leader, Volen Siderov, made it to the run-off in the presidential election. After 2009, however, the GERB Party (the incumbent governing party in Bulgaria) managed to attract a considerable number of former Attack supporters. Today, only about 6 to 7 percent of the electorate votes for the Attack Party. n In practice, the smaller extreme right-wing organisations do not take part in the national and local elections, but they are very active in certain youth milieus and among football fans. The fact that they participate in the so-called »Loukov March«, which has been organised on an annual basis ever since 2008, suggests that they might join forces, although in practice this seems unlikely. ANTONIY TODOROV | THE EXTREME RIGHT WING IN BULGARIA Contents 1. Historical Background: From the Transition Period to Now ....................1 2. Ideological Profile ......................................................3 2.1 Minorities as Scapegoats ................................................3 2.2 The Unity of the Nation and the Strong State ................................3 2.3 Foreign Powers .......................................................4 3. -

San Marino Country Profile

COUNTRY PROFILE RepubRepubliclic of San Marino as of October 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDBACKGROUND............………………………………………………..……………………………………………….. PagPagPagePag eee 333 GENERAL INFORMATIONINFORMATION............…………………………………………………...…………………………………………………... PagPagPagePag eee 666 COAT OF ARMSARMS----FLAGFLAGFLAG............……………………………………………………….………………………………………………………. PagPagPagePag eee 777 RELIGIOUS AND NATIONNATIONALAL HOLIDAYSHOLIDAYS……………………………………..………………………………….. PagPagPagePag eee 888 MILITARY AND POLICE CORPS………….CORPS………….………………………………………………………………………… PaPaPagPa gggeeee 999 SAN MARINOMARINO:: UNESCO WORLD HERITAGEHERITAGE………………………...………………………...………………………...……….………. PagPagPagePag eee 101010 POPULATION AND SOCIASOCIALL INDICATORS.INDICATORS.…………………………………...…………………………………... PagPagPagePag eee 111111 ELECTORAL SYSTEMSYSTEM............………………………………………………………...………………………………………………………... PagPagPagePag eee 11131333 INSTITUTIONSINSTITUTIONS…...…...…...……………………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………….. PagPagPagePag eee 151515 CAPTAINS REGENT...REGENT...………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………….. PagPagPagePag eee 11161666 GREAT AND GENERAL COCOUNCILUNCIL (((OR(OR COUNCIL OF THE SISIXTIESXTIESXTIES))))............………...………... PagPagPagePag eee 11181888 CONGRESS OF STATESTATE…………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………………….. PagPagPagePag eee 22212111 GUARANTORS’ PANEL ON THE CONSTITUTIONALICONSTITUTIONALITYTY OF RULES….RULES….………..……….. PagPagPagePag eee 22232333 COUNCIL OF THE TWELVTWELVEEEE……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

1 Cultural & Social Affairs Department Oic

Cultural & social affairs Department OIC islamophobia Observatory Monthly Bulletin – March 2014 I. Manifestations of Islamophobia: 1. UK: Legoland cancels Muslim family fun day in fear of “guest and employee safety” – Legoland cancelled a family outing organized by a prominent Muslim scholar in fear of guest and staff safety after they received a number of threatening calls, emails and social media posts. The family fun day which was organised by Sheikh Haitham al Haddad of the Muslim Research and Development Foundation (MRDF) for Sunday 9th March and would not be going ahead after a barrage of violent messages were made by far- right Islamophobic extremists. The English Defence League, Casuals United and other far-right groups vowed to hold a protest outside Legoland, many threatening to use violence to prevent the family outing. Legoland issued the following statement: The Legoland Windsor Resort prides itself on welcoming everyone to our wonderful attraction; however due to unfortunate circumstances the private event scheduled for Sunday 9th March will no longer take place. This was an incredibly difficult made after discussions with the organisers and local Thames Valley Police, following the receipt of a number of threatening phone calls, emails and social media posts to the Resort over the last couple of weeks. These alone have led us to conclude that we can no longer guarantee the happy fun family event which was envisaged or the safety of our guests and employees on the day – which is always our number one priority. “Sadly it is our belief that deliberate misinformation fuelled by a small group with a clear agenda was designed expressly to achieve this outcome. -

Electoral Processes Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Electoral Processes Report Candidacy Procedures, Media Access, Voting and Registration Rights, Party Financing, Popular Decision-Making m o c . e b o d a . k c Sustainable Governance o t s - e g Indicators 2018 e v © Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2018 | 1 Electoral Processes Indicator Candidacy Procedures Question How fair are procedures for registering candidates and parties? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = Legal regulations provide for a fair registration procedure for all elections; candidates and parties are not discriminated against. 8-6 = A few restrictions on election procedures discriminate against a small number of candidates and parties. 5-3 = Some unreasonable restrictions on election procedures exist that discriminate against many candidates and parties. 2-1 = Discriminating registration procedures for elections are widespread and prevent a large number of potential candidates or parties from participating. Australia Score 10 The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) is an independent statutory authority that oversees the registration of candidates and parties according to the registration provisions of Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act. The AEC is accountable for the conduct of elections to a cross-party parliamentary committee, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM). JSCEM inquiries into and reports on any issues relating to electoral laws and practices and their administration. There are no significant barriers to registration for any potential candidate or party. A party requires a minimum of 500 members who are on the electoral roll. -

Anti-Communism, Neoliberalisation, Fascism by Bozhin Stiliyanov

Post-Socialist Blues Within Real Existing Capitalism: Anti-Communism, Neoliberalisation, Fascism by Bozhin Stiliyanov Traykov A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Alberta © Bozhin Stiliyanov Traykov, 2020 Abstract This project draws on Alex William’s (2020) contribution to Gramscian studies with the concept of complex hegemony as an emergent, dynamic and fragile process of acquiring power in socio- political economic systems. It examines anti-communism as an ideological element of neoliberal complex hegemony in Bulgaria. By employing a Gramcian politico-historical analysis I explore examples of material and discursive ideological practices of anti-communism. I show that in Bulgaria, anti-communism strives to operate as hegemonic, common-sensual ideology through legislative acts, production of historiography, cultural and educational texts, and newly invented traditions. The project examines the process of rehabilitation of fascist figures and rise of extreme nationalism, together with discrediting of the anti-fascist struggle and demonizing of the welfare state within the totalitarian framework of anti-communism. Historians Enzo Traverso (2016, 2019), Domenico Losurdo (2011) and Ishay Landa (2010, 2016) have traced the undemocratic roots of economic liberalism and its (now silenced) support of fascism against the “Bolshevik threat.” They have shown that, whether enunciated by fascist regimes or by (neo)liberal intellectuals, anti-communism is deeply undemocratic and shares deep mass-phobic disdain for political organizing of the majority. In this dissertation I argue that, in Bulgaria, anti- communism has not only opened the ideological space for extreme right and fascist politics, it has demoralized left political organizing by attacking any attempts for a politics of socio- economic justice as tyrannical.