Race, Class, and Gender in Beulah and Bernie Mac

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Read Book ^ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa / TKNZIXTAS6A9

7FDWAO06DEBA eBook \ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa Madagascar: Escape 2 A frica Filesize: 5.28 MB Reviews Completely among the best pdf I actually have possibly read through. It is probably the most awesome pdf we have read. You wont really feel monotony at whenever you want of your time (that's what catalogs are for about in the event you ask me). (Prof. Martine Lesch) DISCLAIMER | DMCA QO2SVENHMT8D < Doc ^ Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa MADAGASCAR: ESCAPE 2 AFRICA To get Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa PDF, make sure you click the button under and save the ebook or have access to other information that are in conjuction with MADAGASCAR: ESCAPE 2 AFRICA book. Alphascript Publishing Feb 2010, 2010. Taschenbuch. Condition: Neu. Neuware - Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa is a 2008 sequel to the 2005 film Madagascar, about the continuing adventures of Alex the Lion, Marty the Zebra, Melman the Girae, and Gloria the Hippo. It is directed by Eric Darnell and written by Etan Cohen. It stars the voices of Ben Stiller, Chris Rock, David Schwimmer, Jada Pinkett Smith, Sacha Baron Cohen, Cedric the Entertainer, and Andy Richter. Also providing voices are Bernie Mac, Alec Baldwin, Sherri Shepherd and will.i.am. It was produced by DreamWorks Animation and distributed by Paramount Pictures, and was released on November 7, 2008. The film starts as a prequel, showing a small part of Alex's early life, including his capture by hunters. It soon moves to shortly aer the point where the original le o, with the animals deciding to return to New York. They board an airplane in Madagascar, but crash- land in Africa, where each of the central characters meets others of the same species; Alex is reunited with his parents. -

Walter Latham Biography

Walter Latham Often referred to as "The King of Comedy,” Walter Latham is grateful for the humble upbringing and everyday challenges that shaped his early life, and instilled in him a fierce passion that led to his success as a business mogul and humanitarian. Born to a single mother in East New York, Brooklyn, Latham soon found himself in a similar situation, becoming a father at the young age of 18, and struggling to get by with odd jobs and a brief stint in the United States Air Force. At 20, he caught a break with a permanent position at the American Express Call Center in Greensboro, NC and was thrilled to finally provide healthcare for his son, even though he knew he was bound for something greater. Inspiration soon struck Latham, after attending a performance by his childhood friend, MC Lyte, when he realized his calling was to produce concerts. He borrowed money from his mother and produced his first concert in a nightclub. The headline act didn’t show and Latham had to refund the patrons their money but what he learned from this unfortunate experience would change his path forever. Latham decided to produce more concerts but mitigate his losses by soliciting sponsorships. He wrote and mailed 50 letters to various corporations about promoting a southeast tour with the hottest comedians. When Coors Brewing Company expressed interest, Latham soon found himself, at age 21, standing in a boardroom of top executives pitching his comedy idea. His first comedy tour featured Chris Tucker and Bill Bellamy and Coors was so impressed they asked Latham to do another. -

!!!Grow!A!Pair!Of…Wings!

FRESH PRODUCE’d LA and Amelia Phillips present the world premiere of !!!grow!a!pair!of…wings! written by Amelia Phillips directed by Stacie Hadgikosti Guided by the whimsical ghost of her Holocaust survivor grandfather, Sarah Klein clumsily struggles to emerge from her mid-twenties as more than just the good student, the good daughter, the good girlfriend. Saddled by an overbearing mother, an unappreciative boyfriend and an overly competitive sister, Sarah must define her unique place in the world, face her fears, embrace her roots, and of course, grow a pair of...wings. Starring: Amelia Phillips, Riva Di Paola, Barry Vigon, Greg Nussen, Tyler Cook, Jennie Fahn And Robert Dominick Jones April&17th+&May&10th& The!Lounge!Theatre! 6201!Santa!Monica!Blvd.! Los!Angeles,!CA!!90038! Tickets: $25 [4/17 - 4/26 Fridays & Saturdays, 8pm. Sundays 2pm and 7pm.] [4/30 - 5/10 Thursday, Fridays & Saturdays, 8pm. Sundays, 7pm.] For Tickets and Info: www.ameliap.com/wings www.wingstheplay.brownpapertickets.com Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/wingstheplay For more info about FRESH PRODUCE’d visit www.getfreshproduced.com Media Contact: Riva Di Paola [email protected] www.getfreshproduced.com Stacie!Hadgikosti-(director)!is!thrilled!to!be!making!her!directorial!debut!with!Amelia!Phillips'!new!play,!"grow!a!pair! of…wings."!!She!was!a!part!of!the!original!workshop!production!and!is!excited!to!see!the!play!grow!its!own!set!of!wings.!!Stacie! received!her!Bachelor!of!Arts!in!Theatre!from!Western!Michigan!University!and!her!Master!of!Fine!Arts!in!Acting!from!Purdue! -

Chinese in Hollywood

Chinese Historical Society EWS'N of Southern California 411 Bernard Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Phone: 323-222-0856 Email: [email protected] OTES Website: www.chssc.org FEBRUARY 2014 II Jack Ong is an American-born Chinese actor, writer and activist with a professional background in print journal Chinese in ism, marketing, advertising and public relations. Jack is a licensed minister with the Missionary Church and executive director of The Dr. Haing S. Ngor Founda tion, which he established in 1991 with the late Oscar Hollywood winning actor of"The Killing Fields." A dramatic as well as comedic actor, Jack created the role of Welling ton Po, "eccentric billionaire," on the Showtime series, "Hoop Life"; and improvised the "Funky Peasant" dance before his close-up death scene in the horror Book presentation by author Jenny Cho movie, "Lep in the Hood: Leprechaun 5." His credits also include guest starring roles on such TV shows as followed by a panel discussion with actors "ER," "Friends," "The Bernie Mac Show," "Still Standing," "Dharma & Greg," "Touched By An Angel," "V.I.P.," "Chicago Hope," "The Simpsons," and Jack Ong, Kelvin Han Yee and Keane Young. "Beverly Hills 90210." He was seen as a veggie-chopping, attitude-copping chef on the Kan-Tong Fried Rice commercials. His acting and ministry careers crossed when he married couples on TV's "The Young and the Restless" and "Hunter," and in the film "For Keeps"; he also plays a minister in "Cannes Man." Other movie credits include "Art School Confidential," "Akeelah and the Bee," "Next," "National Lampoon's Gold Diggers," "China Cry," "The Iron Triangle," Wednesday, February 5, 2014- 6:30p.m. -

For Immediate Release

‘HEALING HANDS’ CAST BIOS EDDIE CIBRIAN (Buddy Hoyt) – A versatile actor who continues to expand his career in television and film, Eddie Cibrian is fast becoming one of the leading young actors in the business today. Born and raised in California, Cibrian began his acting career at the age of 12, landing a Coca-Cola commercial on his very first audition. Following the success of that spot, Cibrian appeared in numerous other national commercials. Upon entering high school, Cibrian decided to put his acting career on hold to pursue his other passion: Sports. He excelled in every sport he competed in – football, baseball, soccer and volleyball – and graduated high school with several All-State honors. Cibrian continued his successful athletic career when he entered UCLA’s football program in the fall of 1991. Unfortunately, an injury during his first year on the team left Cibrian sidelined, so he decided to return to acting. Cibrian immediately landed several national commercials and soon after, starred in Malcolm- Jamal Warner’s Emmy® Award winning television special “Kids Killing Kids.” The attention Cibrian garnered for his appearance on Warner’s special led to several soap opera auditions, including one for “The Young and the Restless.” The show’s producers were impressed with Cibrian’s acting abilities and created a character for him on the show, that of the conniving Matt Clark. Within three months, Cibrian had received so much fan mail that CBS signed him to a three-year contract. After appearing on “The Young and the Restless” for two years, Cibrian starred in several television shows including “The Bold and the Beautiful,” “Baywatch Nights,” “Beverly Hills, 90210,” “Sabrina The Teenage Witch” and “Saved by the Bell: The College Years.” It was not long before Aaron Spelling offered Cibrian the starring role of Cole Deschanel on the NBC daytime drama, “Sunset Beach.” Just five months after his debut, TV Guide named Cibrian one of Daytime’s 12 Hottest Stars. -

Bailey, Dennis Resume

Dennis Bailey Height: 6’ Weight: 185 lbs Eyes: Brown Hair: Salt and Pepper Film Ocean’s 13 Supporting WB, Steven Soderbergh The Trip Supporting Artesian, Miles Swain Ways of the Flesh Supporting Columbia, Dennis Cooper Man of the Year Supporting Working Title, Dirk Shafer Television Good Christian Belles (Pilot) Co-star ABC-TV, Alan Poul Chase Co-star NBC, Dermott Brown The Simpsons Guest Star FOX, David Mirkin The Bernie Mac Show Guest Star FOX, Lee Shallat Chemel General Hospital Recurring ABC, Gloria Monty Melrose Place Guest Star FOX Crossing Jordan Guest Star NBC, Dick Lowry The Drew Carey Show Guest Star ABC, Brian Roberts Days of Our Lives Recurring NBC Sabrina, The Teenage Witch Recurring ABC, Melissa Joan Hart Martin Guest Star FOX, Garren Keith Dave’s World Guest Star CBS LA Law Guest Star NBC, Eric Laneuville Murder, She Wrote Guest Star CBS Columbo Guest Star NBC, Darryl Duke Dallas Recurring CBS, Leonard Pressman China Beach Recurring ABC, Mimi Leder Ally McBeal Recurring FOX, Kenny Ortega Television- MOW Search and Rescue (Pilot) Guest Star NBC, Robert Conrad Sworn to Vengeance Guest Star CBS, Peter Hunt Last Voyage of the Morrow Castle Guest Star HBO Theatre- Broadway Gemini Francis Geminiani Helen Hayes Leader of the Pack Gus Sharkey Ambassador Marriage of Figaro Figaro Circle in the Square Theatre- Off-Broadway Preppies Bogsy Promenade Professionally Speaking Teacher St. Peter’s Wonderland Alan Hudson Guild Theatre- Regional Dead White Males Principal Pettlogg Sustainable Theatre The Immigrant The Immigrant Actor’s Theatre, Louisville Are We There Yet? The Suitor Williamstown Merry Wives of Windsor Abraham Slender The Old Globe Blue Window Griever Atlanta Alliance Commercial List available upon request . -

TV Listings FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 2017

TV listings FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 2017 05:25 The Muppets 11:15 Hanging Up 14:00 Ploddy Police Car On The Video On Patrol Show 07:10 Lilo & Stitch 13:00 Crazy On The Outside Case 05:55 Bondi Ink. 04:50 Til Death 08:40 Lilo & Stitch 2 14:45 Lovesick 15:30 Curious George 06:50 Catch A Contractor 05:15 Bette! 09:55 Herbie Fully Loaded 16:45 Pixels 17:15 Paws 07:40 Lip Sync Battle 05:40 American Housewife 02:15 Metro 11:40 The Muppets 18:30 Valentine’s Day 19:00 The Nutcracker Sweet 08:05 Lip Sync Battle 06:05 The Mick 04:00 Bad Company 13:30 Chicken Little 20:30 Break Point 20:30 Ploddy Police Car On The 08:30 Disorderly Conduct: 06:30 The Bernie Mac Show 06:00 Fast & Furious 7 15:00 Hotel Transylvania 2 22:00 Undercover Brother Case Video On Patrol 06:55 2 Broke Girls 08:15 Jurassic Hunters 16:30 Beverly Hills Chihuahua 23:30 Two-Bit Waltz 22:00 Memory Loss 09:20 Sweat Inc. 07:20 Late Night With Seth 09:45 Metro 18:05 The Princess Diaries 2: 23:30 Paws 10:10 Hungry Investors Meyers 11:30 Bad Company Royal Engagement 11:00 Life Or Debt 08:10 The Ellen DeGeneres 13:30 Fast & Furious 7 20:00 Mary Poppins 11:50 Bondi Ink. Show 15:45 Big Game 22:20 Hotel Transylvania 2 12:40 Disaster Date 09:00 The Tonight Show 17:30 Hitting The Apex 23:50 Chicken Little 13:05 Disaster Date Starring Jimmy Fallon 20:00 Hudson Hawk 00:00 WarGames 13:30 Lip Sync Battle 09:50 Til Death 21:45 The Man From U.N.C.L.E. -

View This Page

16 發光的城市 A R O U N D T O W N FRIDAY, JANUARY 23, 2009 • TAIPEI TIMES OTHER RELEASES COMPILED BY MARTIN WILLIAMS Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea Better The pick of this week’s other releases is an award-winning film from legendary Japanese than the book animator Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away). Sort-of- mermaid Ponyo longs to know Brendan Fraser’s chunkiness as a kind of bulked-up more about the world out of the ocean and soon becomes the pet Indiana Jones is one of the few of a boy who lives in a seaside home. Her disappearance jarring notes in ‘Inkheart,’ an otherwise triggers a hunt that results in wonderful sequences that commendable minor fantasy film will captivate adults and children alike. Miyazaki’s box office hit is glorious proof that possibilities still exist for BY Ian BartholomeW traditional animation techniques. It’s being screened in STAFF REPORTER Taiwan in both Mandarin and Japanese-language versions. have seen rather a lot of up a mood of comic adventure. There is Yes Man Brendan Fraser recently, what none of the moralizing of Narnia or the We with The Mummy: Tomb of philosophizing of The Golden Compass, In this comedy outing, Jim the Dragon Emperor and Journey at the but just a good yarn with lots of fascinating Carrey transforms from a Center of the Earth both released in the characters in it. At the center is Meggie, soulless loan officer who second half of last year. He’s back again, Mo’s daughter and companion, an aspiring will only say “no” into an and while Inkheart is a vastly superior writer, who only gradually realizes why her increasingly havoc-stricken film to his previous efforts, his presence father has never read her a bedtime story man who can only say “yes.” TV contributes little to its success. -

Analyzing the Movie-Viewing Audience

MEDIA AT THE MOVIES: ANALYZING THE MOVIE-VIEWING AUDIENCE By SEAN MICHAEL MAXFIELD A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 This thesis is dedicated to my family, all the survey/questionnaire people who have the courage and patience to ask strangers for help in getting a job done, and to all people who in some way contributed to this thesis, great or small. It is finally done! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the following people for their help and encouragement, as well as giving of their time and talent, throughout this thesis process. First, I would like to thank my parents and other family members for their time, support, love, and monetary aid, without which I would not even be writing this thesis. I would especially like to thank my parents for their assistance in getting the Orlando theater to help me with the surveys. In the same way, I would like to thank the theaters that allowed me the time and opportunity to get people’s ideas on paper about the movies. Special thanks go to Cinemark Theater in Orlando and Gator Cinemas in Gainesville. They both get ten stars! A special thank-you goes to fellow graduate student Todd Holmes, who got me through the first leg of this thesis when we originally proposed its beginning for our research class. He was there to give this baby life. I would also like to thank my chair, James Babanikos, for taking time to listen to this thesis idea and running with it. -

2008-2009 Emmy Nominations

2008-2009 Emmy Nominations Chicago/Midwest Chapter National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Tabulated by: Baker Tilly Virchow Krause, LLP 205 North Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60601 1 Category #1 Outstanding Achievement within a Regularly Scheduled News Program – Spot Coverage & Breaking News (Award to the Team of Reporters, Producers, Videographers, Editors, Directors, and Assignment Editors) • SportsNite VanLier/Kerr Passing: Lissa Christman, Charlie Schumacher, Kevin Cross, Executive Producers; Bill Koplos, Willie Parker, Producers; Tim Folke, Assignment Manager; Joe Collins, Assignment Editor; Luke Stuckmeyer, Gail Fischer, Chuck Garfien, Reporters; Eric Peterson, Director; Jared Storck, Associate Producer; Todd Williams, Videographer. Comcast SportsNet Chicago • The Historic Inauguration of President Barack Obama: Cheryl Burton, Charles Thomas, Andy Shaw, Reporters; Jason Knowles, Doug Whitmire, Derrick Robinson, Richard Hillengas, Jim Mastri, Producers. WLS • Spring Washout: Lori Waldon, Executive Producer; Jessica Schmid, Eric Marshall, Producers; Terry Sater, Kathy Mykleby, Toya Washington, Mark Baden, Reporters. WISN • Drew Peterson Arrested: Jennifer Lay-Riske, Producer; Joe Kolina, Executive Producer; Bob Sirott, Allison Rosati, Marion Brooks, Lauren Jiggetts, Anthony Ponce, Phil Rogers, Alex Perez, Reporters; Patrick Lake, Director; Stephanie Streff, Anita Selvaggio, Assignment Editors. WMAQ Category #2-a. Outstanding Achievement within a Regularly Scheduled News Program – Single Investigative Report (Award to the Reporter/Producer) • Illegal Gambling: Aaron Diamant, Reporter; Stephanie Graham, Maureen Mack, Ira Klusendorf, Joe Eufemi, Paul Marble, Justin Tiedemann, Producers. WTMJ • Property Taxes: Marsha Bartel, Chuck Quinzio, Lou Hinkhouse, Producers; Dane Placko, Reporter. WFLD • Murder or Suicide?: Dan Schwab, Lou Hinkhouse, Dartise Johnson, Producers; Jeff Goldblatt, Reporter. WFLD • Highway Workers: Marsha Bartel, Chris Willadsen, Lou Hinkhouse, Producers; Dane Placko, Reporter. -

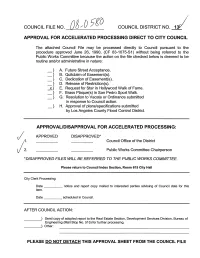

Council File No. Council District No. 1/ Approval for Accelerated Processing Direct to City Council

COUNCIL FILE NO. COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 1/ APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-S1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s) . ..10 E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* / Council Office of the District /,: Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date ____ notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ____, Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS- E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles MAR 0 6 2008 Honorable Members: C.